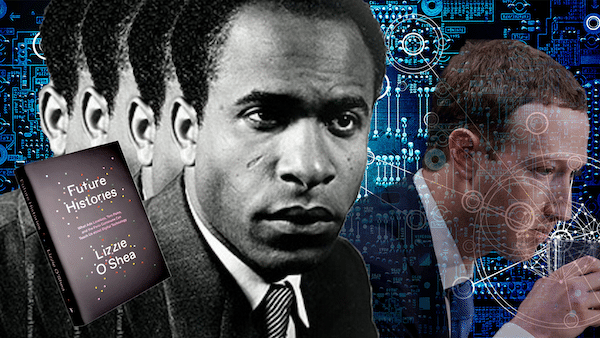

Frantz Fanon, the writer and psychiatrist born in the French colony of Martinique, is perhaps best known for his contribution to our understanding of race and colonialism. He produced a powerful and nuanced body of work before his death in 1961, centered on his experiences and reflections upon racism. His writings grappled with the kind of future that might be possible for people who have lived through these systems of oppression. For Fanon, anti-black racism was a feature of skewed rationality, a systemic problem, rather than an essential feature of human society.(1) He created a language for talking about these ideas, and theoretical basis for understanding them.

The importance of Fanon’s contribution to our thinking about race and colonialism is indisputable. However in a chapter of my book Future Histories, I set out how I think his work has relevance in other ways also. More specifically, Fanon’s ideas around self-determination have much to offer us as we seek to understand, and resist, some of the most profound personal challenges of living in the digital age. Fanon provided an explanation of how colonialism works–how both the colonizer and the person being colonized take on roles and practices that make colonialism seem inevitable and unbeatable. He argued that liberation was possible, even in the context of significant oppression. These arguments continue to find applicability after his death because, I argue, the questions Fanon grappled with continually re-present themselves, namely: how do we create ourselves in a world in which our identity is pre-determined for us?

The eyes of technology capitalism see everything we do, and they share their insights with the snooping governments. In the digital environment, the history of our sense of self is constantly written and re-written by others. Those that hold power over our digital lives, from private industry and government, do so in a way that is almost hegemonic. Our behaviour is tracked and predicted, we are categorized and judged. This bears similarities to Fanon’s reflections about seeing himself, as a black man, in a world dominated by white supremacy. He explained how his identity was not his own, how the white man had ‘woven me out of a thousand details, anecdotes, stories.’ The experience of being black was, by virtue of being black, not an experience. There was no agency in how his identity was determined; no way to escape the judgments about him; no sense that he possessed autonomy. His identity was fixed: ‘I am overdetermined from the exterior. I am not the slave of the “idea” that others have of me but of my appearance.’(2)

To be clear, our experience of having our minds colonized is not comparable to the gravity, violence, and horrors of actual colonization, nor the experience of living in a deeply racist society. Relating Fanon to problems of the digital age reflects an attempt to take his work seriously, to treat his thinking not as something locked in its time or place, much as we extend this generosity to other thinkers like Marx, Lenin or Freud. Moreover, I would argue there is actually something dehumanising about how technology capitalism has presided over discrimination and impoverishment, using potentially transformative technology to usher in a new gilded age. There is violence in how the government uses technology to incarcerate and kill while claiming its practices and weaponry are more precise and neutral than ever. ‘Fanon dedicated his life,’ according to philosopher Louis Ricardo Gordon, ‘to breaking free of the weighted expectations of consciousness without freedom.’(3) This objective continues to hold relevance in our experience of modern digital life.

The pivotal experience for Fanon was his involvement in the Algerian war of independence. Among his writings on this period, he specifically explained how struggle manifested in technological forms. Fanon wrote about how prior to the war of independence, the radio had ‘an extremely important negative valence’ for Algerians, understood it to be ‘a material representation of the colonial configuration.’(4) But after the revolution broke out, Algerians began to make their own news, and the radio was a critically important way of distributing it cheaply to a population with low levels of literacy. The radio represented access not just to news, but ‘access to the only means of entering into communication with the Revolution, of living with it.’(5) The radio transformed from being technology of the oppressor into something that allowed Algerians to define their own sense of self, ‘to become a reverberating element of the vast network of meanings born of the liberating combat.’(6)

Even in a technologically-saturated world, in which human beings are categorised, surveilled and discriminated against, it is possible for us to carve out space for our own identity and shape our destiny. Though his analysis was informed by his experience of being black in a racist society, Fanon’s body of work was never defeatist. In diagnosing the complex and deep-rooted nature of racism, he did not advocate a defensive retreat into a fixed sense of identity or into racial nationalism. His ultimate vision was emancipatory: he always questioned not only why racism existed, but also how it could be transcended. The loss of dignity was reversible for Fanon, through struggle.(7)

We need a kind of digital self-determination from surveillance capitalism and the state. Digital self-determination will involve making use of the technical tools available to communicate freely. But it will also require that we enjoy autonomy from manipulation by the vast industry of data miners and advertisers, which tries to shape our identity around consumption. We need to change legal structures around data and its use, and design information infrastructure in ways that favour de-centralisation, rather than centralisation in the hands of government and corporations. Digital self-determination must also be about designing online spaces and devices that are welcoming, and give us control over our participation rather than creating a dynamic of addiction. It is about the freedom to question; to freely determine our sense of self, both in digital environments and outside of them.

‘O my body!’ pleaded Frantz Fanon, in the final line of his ground-breaking book, Black Skin, White Masks, ‘Make of me always a man who questions!’(8) It is an plea that remains as relevant as ever today, as we question the structure of power and oppression in the digital age.

Lizzie O’Shea is the author of Future Histories: What Ada Lovelace, Tom Paine, and the Paris Commune Can Teach Us about Digital Technology – 50% off until Tuesday, July 16th at 11:59PM EST as part of our Beach Reads sale!