Facebook’s Mark Zuckerberg is in the spotlight for “dining with far-right figures,” and their influence over the information that appears in your feed is apparent. However, Facebook isn’t the only Silicon Valley firm that’s masquerading as nonpartisan as it curates the “facts” you see in ads, posts, or searches: Google, Twitter, Microsoft, and others are deeply wedded to the U.S. security state and the billionaires it upholds.

Walter Lippmann’s groundbreaking 1922 study of the news media, “Public Opinion,” begins with a chapter titled, “The World Outside and the Pictures in our Heads,” in which he presents the media as a bottleneck through which information about the world beyond the perception of our senses must pass. Aside from the question of which stories get passed through that bottleneck, which information about an event that survives the crucible of condensation into an article, news bulletin or wire is determined by the biases of the writer and editor. In turn, control over that information bottleneck gives the controller incredible power to shape the consciousness of readers about “the world outside”–the “manufacturing of consent,” as Lippmann originally described it.

The depth of information about the world made available by the internet seems to remove the bottleneck about which Lippmann fretted–indeed, a generation of techie evangelists tried to present it in just such a manner–but the truth is that it only further obscured both the bottlenecks and the crucibles that distill information for our consumption.

The media giants that control our access to information, from search engines like Google to social media like Facebook, have turned themselves into portals to the world and present themselves as impartial in that role. However, behind a facade of separateness, strong connecting links bind the tech giants to the oligarchy and security state on which they rely, giving the interests of the elite determinative influence over which information we access.

This article will expose and discuss some of the many ways this shady web of influence and oversight operates.

The door between these tech companies and intelligence agencies, think tanks, defense contractors and security companies is constantly revolving, especially at the higher echelons of important departments, like cybersecurity. Notably, many of these companies cater along partisan lines depending on the political proclivities of their owners, in a bid to tip the scales toward their point of view.

They have embraced this role as an information portal, offering special “news” sections on their platforms. They are rolling out new apps to judge the trustworthiness of news sources. Facebook and Google, in particular, have also become two of the largest funders of journalism around the world, helping to further entrench State Department-approved models of truth in key hotspots of geopolitical interest.

This cyberpunk dystopia isn’t a new perversion of a previously free internet, though–in fact, it is the internet’s raison d’être in the first place.

It’s astory so old, it goes back to the very origins of computing, as a tool for census counting in pursuit of racist immigration policies, and the internet, born of the Pentagon’s attempt to model whole societies for the purposes of improving counterinsurgency warfare in Southeast Asia.

Right hook

Facebook has been under fire, most memorably from Rep. Alexandria Ocasio Cortez, since news broke from Politico that Mark Zuckerberg, the great Facebook wunderkind, has been palling around with right-wing figures for quite some time. Politico documented how Zuckerberg’s private dinners have fed a whos-who of conservative talking heads and hosts from across the corporate media, including Fox’s Tucker Carlson, Washington Free Beacon editor Matt Continetti, conservative commentator Ben Shapiro, and Byron York, The Washington Examiner’s chief political correspondent, and others. There’s no word on whether Zuckerberg made them slaughter their own meat, however.

One Silicon Valley cybersecurity researcher and former government official is quoted as saying “the fear is that Zuckerberg is trying to appease the Trump administration by not cracking down on right-wing propaganda.”

“For years, Mark Zuckerberg has met with elected officials and thought leaders all across the political spectrum,” a Facebook spokesperson said. Yet when The Intercept put that claim to the test, they couldn’t find a single left-wing figure invited to his private California estate for one of these wine and dine symposia on free speech.

Facebook News

Zuckerberg’s swearing off a right-wing bias rang hollower still when Facebook debuted a specialized news tab on its app later in October 2019 that included stories from the right-wing site Breitbart, once described by co-founder Steve Bannon, Trump’s former top adviser, as “the platform for the alt-right.”

Zuckerberg reassured journalists at a “fireside chat” that Facebook has “objective standards” for news, calling the new tab “a space that is dedicated to high-quality and curated news.”

Breitbart, mind you, has defended the “glorious heritage” of the Confederate flag, arguing that the banner of a rebel state founded on the basis of protecting the enslavement of Black people wasn’t racist. Some other heinously incendiary headlines include “The Solution to Online ‘Harassment’ is Simple: Women Should Log Off”; “World Health Organization Report: Tr*nnies 49xs Higher HIV Rate”; and “Gabby Giffords: The Gun Control Movement’s Human Shield.” That’s in addition to its more mundanely inaccurate reporting, such mistaking German soccer star Lucas Podolski for the leader of a Spanish human trafficking ring. It’s also where Trump’s immigration war chief Stephen Miller trafficked white nationalism to a mainstream audience

Russiagate creates the ‘troll army’ narrative

For the social media giants, a new opportunity to double down on methods of social control came from the rise of the Russiagate conspiracy, promulgated by a growing corporate media-Democratic Party-intelligence community rallying cry that Donald Trump’s 2016 election victory was the work of Russian meddling rather than the United States’ outdated Electoral College system that was created as a progressive roadblock by the country’s founders.

The opening shot of this information war was the accusation by U.S. intelligence that hacker Guccifer 2.0 had worked on behalf of Russia to hack the Democratic National Committee’s servers and steal damning emails exposing the corrupt inner workings of the DNC —particularly how it cooked the books for Hillary Clinton in the primary race—to whom the DNC had become deeply financially indebted. When the emails were published by WikiLeaks in the summer and fall of 2016, U.S. intelligence claimed the site was also controlled by the Kremlin.

Facebook ads linked to a Russian effort to disrupt the American political process are displayed as, from left, Google’s Senior Vice President and General Counsel Kent Walker, Facebook’s General Counsel Colin Stretch, and Twitter’s Acting General Counsel Sean Edgett, testify during a House Intelligence Committee hearing on Capitol Hill in Washington, Wednesday, Nov. 1, 2017. (AP Photo/Manuel Balce Ceneta)

Further fuel for the Russiagate fire came in the form of accusations that the St. Petersburg-based Internet Research Agency (IRA) had flooded U.S. social media with trolls, sinking hundreds of thousands of dollars into advertisements intended to sway voters toward Trump and away from Clinton, as well as more generally sow social chaos by promoting discussion of divisive topics such as racial, gender, and class inequalities.

Popular pressure on social media companies to prune users’ news feeds grew dramatically in the wake of the 2016 U.S. presidential election. In January 2017, a report supposedly based on the conclusions of 17 intelligence agencies, but in reality, drafted almost exclusively by the fiercely anti-Trump CIA, presented the narrative of a “Russian influence campaign,” setting the stage for vetting the veracity of newsfeed information based on standards set out by the security state.

A year later, the Pentagon and White House announced a shift in global strategy toward “great power competition” with Russia and China, saying that “Inter-state strategic competition, not terrorism, is now the primary concern in U.S. national security.”

Facebook first outlined their response in an April 2017 white paper on combating “false news,” recognizing that bots and spam accounts could spread a particular narrative quickly across the platform. The white paper didn’t mention any countries, and Facebook initially denied that a Russian influence operation had taken place, but soon the social media giant stepped into line with the intelligence community by claiming later that year to have uncovered proof that a relative handful of ads bought with Russian rubles had tipped the scales in favor of Trump.

“Social media trolls,” and the “disinformation campaigns” they ostensibly waged, soon became the generalized tocsin for widening control over social media news feeds. The intelligence community, which has formed an anti-Trump faction of the U.S. security state, warned against future attempts to influence elections in 2018 and 2020–attacks that have never materialized.

The irony was that some of the gamekeepers were already poaching, with cybersecurity firm New Knowledge launching a far more potent troll campaign in Alabama’s 2017 special election, which it then sought to blame on Russian actors.

New knowledge, old tactics

A key December 2018 report that claimed to lay out the “tactics & tropes” of the IRA, and blasted Facebook and Google for their lack of cooperation with the Russiagate probe, was prepared by New Knowledge, a cybersecurity company revealed just weeks later to have helped orchestrate massive election meddling in Alabama’s 2017 special election.

Facebook suspended the account of New Knowledge CEO Jonathon Morgan, who is also a former special adviser to the State Department, for having directed a crew of political functionaries who pushed story after fake news story, even posing as Alabama Republicans in order to tarnish their image, all in an effort to convince voters not to vote for Republican candidate and slavery and pedophilia defender Roy Moore.

In three weeks’ time, New Knowledge spent the same amount of money on ads that the IRA was supposed to have spent during several years of the U.S. presidential campaign: $100,000. Then on top of it all, New Knowledge turned around and tried to cover their tracks by painting the disinformation op as the work of “Russian trolls.”

Bad actors

Fast forward to August 2018: along with other social media platforms with whom it shares tips and information, Facebook has begun targeting voices from, and in defense of, nations targeted by the U.S. State Department for regime change. However, it’s not just Russians any more: some of the voices silenced in the semi-regular sweeping round of bans include Cubans, Venezuelans, Iranians, and Chinese as well. Frequently, these bans coincide with elections in the U.S., though Facebook typically avoids citing election interference in its press releases, giving the media free reign to speculate.

Standard fare is for tips on “inauthentic content” to come from one of two places: the Atlantic Council’s Digital Forensic Research Lab (DFRL) or cybersecurity firm FireEye. These firms are anything but impartial and independent.

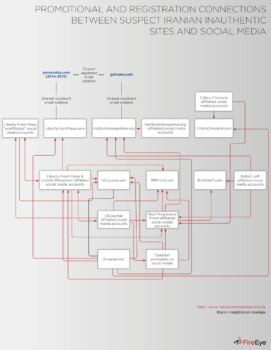

A FireEye graphic purporting to show components of a suspected Iranian influence operation

The first such tip came in August 2018 in a report by FireEye on Iranian and Russian “coordinated inauthentic behavior,” according to Nathaniel Gleicher, Facebook’s tsar of Cybersecurity Policy and former neocon think tanker. FireEye expressed “moderate confidence” in its findings, with TechCrunch noting at the time that “the Iranian networks were not alleged to be necessarily the product of state-backed operations, but of course the implication is there and not at all unreasonable.”

The U.S. State Department’s Iran Action Group later cited the Facebook and Twitter takedowns in a September 2018 report titled “Outlaw Regime: A Chronicle of Iran’s Destructive Activities,” in which it attempted to lay out the ideological groundwork for its present offensive against Iran. Curiously, the State Department’s report didn’t mention FireEye’s report.

The sweeps soon became regular, following a standard pattern. Another takedown in May 2019 saw Twitter and Facebook cooperate to cull “more than 2,800 inauthentic accounts originating in Iran,” according to Twitter Site Integrity Chief Yoel Roth, as well as 51 accounts, 36 pages, seven groups and three Instagram accounts on Facebook, according to Gleicher. The tip came from FireEye. Sputnik News noted the shady nature of the move, with Facebook admitting it never looked at the FireEye report before acting–a report that expressed low confidence in the researchers’ findings.

In a previous takedown in February, Facebook and Twitter again shared intel, this time from the DFRL, showing the accounts were involved in “attempted influence campaigns” by Iran, Venezuela and Russia. However, on a conference call with reporters, Gleicher was forced to admit that Facebook couldn’t actually tie any of the activity to the Iranian government, saying only “we can prove and feel confident” in their origins, without providing further evidence.

FireEye and DRFL

FireEye isn’t just some well-meaning cybersecurity startup, though: since 2009, FireEye has collected venture capital funding from In-Q-Tel, the CIA’s investment arm. In a statement at the time, In-Q-Tel said it would maintain a “strategic partnership” with FireEye, calling it a “critical addition to our strategic investment portfolio for security technologies.”

Started as In-Q-It in 1999 with CIA seed money, In-Q-Tel’s investment has poured money into firms judged useful to the U.S. intelligence service, such as the failing company Keyhole, which it bought in 2003. Spun off from a video game outfit, Keyhole aimed to stitch together satellite images and aerial photographs of the planet to form a 3-D digital world that users could navigate.

Buttressed with CIA funds, Keyhole partnered with the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency to provide essential services for the 2003 U.S. invasion of Iraq. Google bought the company the following year, redubbing it as Google Earth, and acquiring with it In-Q-Tel executive Rob Painter, who sat on Keyhole’s board of directors and provided a new link between Google and the U.S. intelligence and defense contracting spheres.

The other tip source, the Digital Forensic Research Lab, is a division of the Atlantic Council which, while a registered 501(c)3 nonprofit, is only proforma independent of the U.S. state as one of the preeminent Washington think tanks influencing foreign policy.

In its About Us section, DFRL says its mission is to “identify, expose, and explain disinformation where and when it occurs using open source research; to promote objective truth as a foundation of government for and by people; to protect democratic institutions and norms from those who would seek to undermine them in the digital engagement space.” Lofty goals, were they not voiced by a think tank that’s funded by a bevy of defense contractors, Gulf monarchies, and even the NATO alliance itself.

Facebook has also buttressed its State Department line-towing credentials by adding to their staff figures like Gleicher, Facebook’s chief of Cybersecurity Policy, who is also a senior associate at the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), another hawkish think tank with major influence on U.S. foreign policy that’s funded by many of the same actors as the Atlantic Council. Likewise, Facebook’s new Public Policy Manager for Ukraine, Kateryna Kruk, is a rabid Russophobe who participated in the 2014 U.S.-backed coup d’etat that brought the fascist Svoboda party to power in Ukraine, turning that country’s government against not only Moscow but their own Russian-speaking Ukrainian minorities.

Guarding you from the news

In August 2018, Microsoft rolled out the NewsGuard app, which vets news outlets according to a list of highly subjective standards presented as the site’s “Nutrition Facts,” which include “gathers and presents information responsibly” and “does not repeatedly publish false content,” among some more mundane items.

The advisory board that oversees NewsGuard is a whos-who of security state figures, including Tom Ridge, the first Secretary of Homeland Security under George W. Bush; Ret. General Michael Hayden, who has headed both the NSA and CIA; and Richard Stengel, a former TIME editor who served as Barack Obama’s Undersecretary of State for Public Diplomacy. In other words, the power over determining what is true and false about U.S. foreign policy falls on central figures who helped craft it.

Newsguard gives Fox News high marks for accuracy.

Naturally, NewsGuard has given conservative outlet Fox News a green checkmark of authenticity and WikiLeaks a red exclamation mark advising caution because, in their words, “this website generally fails to maintain basic standards of accuracy and accountability.” This, despite the fact that NewsGuard later states that “WikiLeaks does not appear to run corrections,” something it faults the site for, “although it almost exclusively publishes primary source documents, which have never been shown to be fake.”

The third-largest investor in NewsGuard is Publicis Groupe, which also owns Qorvis Communications, a consulting firm hired by the Saudi Embassy in Washington “to shape the media coverage of Saudi Arabia” since early 2002, The Intercept reported. Qorvis has provided vital PR coverage for Riyadh’s brutal war in Yemen, about which there was an almost total blackout in the Western media until a U.S.-made bomb dropped from a Saudi plane killed dozens of school children in August 2018. The Intercept noted that in the six months following the outbreak of war, Qorvis billed the Saudi government nearly $7 million for its PR services.

The Saudi monarchy are also major investors in some of the most powerful think tanks in Washington, including the Atlantic Council, which has a seat at the table of Facebook’s anti-fake news campaign.

NewsGuard is also backed by the Knight Foundation, a group that receives funding from the Omidyar Network and Democracy Fund, both part of the agglomeration of institutions managed and supported by eBay founder Pierre Omidyar.

Facebook’s Expanding Media Empire

This clique of far-right figures is really johnny-come-lately to Facebook’s plot to influence your worldview by pruning the information you access on their platform. Casting the initiative as a fulfillment of its responsibility as one of the largest distributors of information on the planet, Facebook began launching in 2017 a slew of ventures that partnered with the world’s leading consent manufacturers to ensure their platform didn’t interfere with the carefully manicured information landscape crafted by billionaire string-pullers like Omidyar and the Saudi Royal family.

By May 2018, Columbia Journalism Review was able to hail Facebook and Google for having sunk more than half a billion dollars into journalism initiatives, making them two of its largest funders on the planet.

The Facebook Journalism Project (FJP), launched in collaboration with the Comcast-dominated Vox Media and the Jeff Bezos-owned Washington Post, aimed to train journalists in what it called “news literacy.” In describing FJP’s mission, the New York Times effectively laid out a blueprint for social control:

The effort calls for the company to forge deeper ties with publishers by collaborating on publishing tools and features before they are released. Facebook will also develop training programs and tools for journalists to teach them how to better search its site to report on news and events. And Facebook wants to help train members of the public to find news sources they trust, while fighting the spread of fake news across its site.

FJP’s partnerships include the Knight Foundation, Poynter Institute, the American Journalism Project, and News Integrity Initiative, all of which are financially tied to the vast Omidyar media empire. Journalists Alexander Rubinstein and Max Blumenthal documented in atomic detail how through this media empire, Omidyar has directed an information war around the world to further U.S. foreign policy.

News integrity initiative

In April 2017, around the same time Facebook was laying out its plans to address the CIA’s claims that Russian bots were spreading election-spoiling disinformation on their platform, Facebook joined up with the Omidyar-backed Democracy Fund, the Ford Foundation, and others to launch News Integrity Initiative, a $14 million consortium rooted in the CUNY School of Journalism that aimed to “advance news literacy, to increase trust in journalism around the world and to better inform the public conversation.” To accomplish this, it would “combat media manipulation” through a network of “journalists, technologists, academic institutions, non-profits, and other organizations.”

Some of NewsiIntegrity Initiative’s projects have included helping to fund the Maastricht-based European Journalism Centre, another journalism training and funding outfit, as well as Internews, a media outlet that gets four-fifths of its overall funding from the U.S. government to nakedly forward U.S. foreign policy from the Middle East to former Soviet republics.

Integrity initiative

Facebook was also a major funder of a British intelligence media front ironically named “Integrity Initiative,” which made it their primary business to push stories hyping up the “Russian threat” to Western Europe. The outfit got its funding from the U.S. government via the State Department, the British government via the Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO), the NATO alliance, and Facebook. The tech giant gave one of Integrity Initiative’s parent organizations, the Smith Richardson Foundation, £100,000 for research and education activities–a scale of funding only outpaced by the U.S. State Department and NATO’s Public Headquarters Division, which gave the group £250,000 and £168,000, respectively.

Integrity Initiative, like so many of the other outfits discussed here, served as a network for journalists and experts, through whom the funders were able to organize vast disinformation campaigns under the aegis of themselves fighting disinformation. The organization was essentially forced to shutter its operations following a damning expose by Anonymous and persistent investigative journalists in late 2018 and early 2019, but it had worked on an international scale under the direction of the Scottish think tank, The Institute for Statecraft, a group masquerading as a charity but actually cooperating closely with British intelligence.

In some cases, Integrity Initiative milled out its employees to ostensibly independent reporting outfits, such as the National Endowment for Democracy-funded Bellingcat; in others, it simply formed media disinformation hubs, such as the Open Information Partnership (OIP). Sputnik’s Kit Klarenberg revealed that the OIP partnered with the Atlantic Council’s Digital Forensic Lab and others to combat “Kremlin disinformation activities” by protecting “vulnerable audiences” with a slew of ostensible corrections. However, between peddling stories about the mysterious Skripal poisoning and amplifying al-Qaeda’s narrative on alleged Syrian government chemical attacks, the real disinformation activities were clearly the workings of the Integrity Initiative network itself.

Foxes in the henhouse: fact-checking at Facebook

Direct right-wing influence over Facebook’s newsfeed arrived in April 2018, when the site began using machine learning to hunt down disinformation previously identified by humans as such, enlisting artificial intelligence in its bid to curate the information you access. However, as the Verge noted at the time, when Zuckerberg goes before Congress and says Facebook’s harmful content problems are being solved by AI, lawmakers think SkyNet or C3-PO, when really it’s more like a Google search.

The humans directing this “Disinformation Google Search” across Facebook are determined by Full Fact, part of the International Fact Checking Network (IFCN), which provides third-party vetting of myriad institutions it deems worthy to verify the factuality of news–although ironically, some fact-checkers apparently weren’t even aware they were supposed to be verifying advertisements, too.

The IFCN’s choices are sometimes questionable, as when the group approved Check Your Fact, a subsidiary of The Daily Caller Foundation, a far-right associated spin site known for hiring white supremacists, as an impartial judge.

But IFCN isn’t the only group that’s partnered with Facebook to sort through mountains of data: while the Cambridge Analytica scandal is well-known, still outside of public awareness is Facebook’s partnership with the Omidyar-connected Knight Foundation as well as the Charles Koch Foundation, part of the network of nonprofits funded by the billionaire industrialists, the arch-conservative Koch Brothers.

Through this partnership, Facebook provided the foundations with a colossal amount of user data in the interests of preventing disinformation campaigns that might influence elections. However, these groups are themselves part of vast billionaire-directed electioneering networks that push the news in their own direction; that Omidyar and Koch are at opposite sides of the truncated U.S. political spectrum is irrelevant, they have the same material interests and utilize ostensibly neutral public policy and objectivity-promoting groups to forward that.

Facebook dragging its feet in handing over enough user data to them has led to threats of withdrawal from the program. The group Social Science One, which has managed the question for Facebook since the AI sorting began in April 2018, has been hesitant to ‘okay’ data divulgence with Knight and Koch after what happened with Cambridge Analytica.

A March 2018 expose by a company whistleblower revealed that political data firm Cambridge Analytica had gained access to the private information of 87 million Americans via Facebook apps that collected data not only on the app’s users, but on their friends as well. Funded primarily by Trump’s fascistic former adviser Steve Bannon and infamous Republican moneyman Robert Mercer, Cambridge Analytica was hired by Trump’s 2016 election campaign to crunch numbers on voters.

According to the New York Times, the firm’s goal was to “map personality traits based on what people had liked on Facebook, and then use that information to target audiences with digital ads.” However, Facebook for years attempted to cover up its complacency with this operation, a very obvious violation of users’ privacy, and even after the expose, continued to claim it wasn’t a data breach because users had consented to divulge the information when they downloaded the apps in question.

At its core, Facebook, like all social media as well as Google, is a huge vacuum for personal information and behavioral data to be used by advertisers and other actors. That’s their business model: selling your information to corporations in order to market you products more effectively, and providing information to the U.S. intelligence community that can help it identify threats before they appear. In this way, social media are the true torch-carriers of ARPANET, the first internet, crafted by the Pentagon’s Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA, now called DARPA) to provide intricate social models for combating communist insurgencies in Southeast Asia.

ARPANET: counterinsurgency computing

In the wake of the Soviet Union launching the first artificial satellite, Sputnik 1, in 1957, the U.S. government rushed to close the technological gap by sponsoring a greater educational focus on the STEM fields on the one hand, but also the development of a secretive emerging technologies R&D bureau to imagine, create, and test the high-tech weapons of the future for the Pentagon to use–what journalist Sharon Weinberger in her history of (D)ARPA called “the imagineers of war.”

ARPA was created the following year and quickly enlisted in defense of anti-communist U.S. puppet Ngô Đình Diệm, whose government in South Vietnam was quickly failing amid a burgeoning communist insurgency led by the National Liberation Front. ARPA’s first big operation, Project AGILE, began in 1961 with the goal of enlisting computers, then clunky machines used primarily for census-counting and artillery trajectory calculations, into helping sort through huge amounts of personal data on citizens in order to better determine when, where, and by whom a rebellion is likely to occur. AGILE’s mission statement, as noted in a 1971 General Accounting Office report, described the program’s goals in part as “Research and development supporting the DOD’s operations in remote areas, associated with the problems of actual or potential limited or subversive wars involving allied or friendly nations in such areas.”

Project AGILE created one of the world’s first predictive behavior models, tested on Thai hill tribes and perfected in Vietnam’s Mekong Delta, where the Pentagon used AGILE’s methods in a deadly new pacification offensive.

By the late 1960s, the disastrous U.S. war in Vietnam and the upheavals of the struggles by Black people for civil rights had helped catapult the U.S. into an unprecedented social crisis. ARPA, too, had expanded dramatically, and just like anti-war and other social justice organizers were looking to the NLF for ideas, so too was ARPA, tasked with crushing the insurgency in South Vietnam and increasingly being enlisted to crush potential insurgency back home in the U.S. as well. The network of computers at various college campuses where ARPA research programs supporting AGILE and other like programs was first connected in 1969. Dubbed the ARPANET, the network soon matched up with law enforcement to create shared dossiers on activists from the Black Panthers to the Redstockings.

The headline on the front page of The Times of Viet Nam, published in Saigon, reads “CIA FINANCING PLANNED COUP D’ETAT,” Monday, Sept. 2, 1963. The story alleges a scheme by the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency to overthrow the government of President Diem of South Vietnam. (AP Photo/Horst Faas)

But if the first internet was such a naked, if not secretive, weapon of class warfare, how come it’s not seen that way today? Only in the 1980s did the internet acquire its present-day image of a facilitator of freedom amid governments’ attempts at control, as a furious rebranding effort sought to convince Americans that computer networks weren’t the harbingers of a technocratic dystopia, but rather a cybernetic utopia–a dynamic that journalist Yasha Levine recounted in his 2018 book “Surveillance Valley: The Secret Military History of the Internet.” Hierarchies would be a thing of the past, once the average person could plug into the total knowledge of humanity at will. This kind of sentiment appealed especially to hardcore libertarians, especially young techies like Steve Jobs, whose powerful Macintosh personal computers promised just such a link, complete with innovative new features like a graphic-user interface and mouse.

ARPANET and other similarly-named networks may have been spun off in privatization schemes during the 1990s dot-com boom, but despite the public image makeover, the relationship between internet-based tech firms and the Pentagon was scarcely different from the early days of ARPA.

For example, Facebook’s Building 8 research lab, which lasted from 2016 through 2018, was started up and headed for nearly all of that time by Regina Dugan, a former director of DARPA. One of the most significant products of Building 8’s work on AI and VR was the Oculus virtual reality headset, which DARPA’s Plan X program manager Frank Pound once told Wired was “like you’re swimming in the internet.” Oculus went to DARPA, which in 2017 turned the VR headset developed by Facebook over to U.S. Cyber Command.

The cyber network became a social network, too. Google co-founders Larry Page and Sergey Brin met at Stanford University’s computer science Ph.D. program in the 1990s–one of the anchors for ARPANET, where they studied under some of its progenitors. The search engine they produced was a catalog for searching through sites on the emerging public internet, but its utility in tracking the connections made by the Google engine between people and the items they searched and predicting what someone might search in the future harkened back to ARPA’s original purpose.

Ok Google, track me

Today, Google’s power over how we gather information about the world and make our subsequent determinations about it is truly massive.

The work of behavioral research psychologist Dr. Robert Epstein has helped expose the power Google holds over public opinion: in 2015, he first described the Search Engine Manipulation Effect in a paper published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, and he has continued to polish the theory ever since.

Epstein wrote in a Politico article at the time titled, “How Google Could Rig the 2016 Election: Google has the ability to drive millions of votes to a candidate with no one the wiser,” that “Google’s search algorithm can easily shift the voting preferences of undecided voters by 20 percent or more–up to 80 percent in some demographic groups–with virtually no one knowing they are being manipulated.”

Google ranks searches according to what it thinks users want to find, resulting in what the company calls “the 10 blue links,” i.e., the first page of search results that pop up after hitting the Enter key. According to a 2014 study, 90 percent of users don’t advance to page 2 of search results, and a 2019 study found that the first 5 links account for two thirds of page 1 clicks. As a result, high placement grants a much greater likelihood of being found and clicked on. With Google accounting for more than 79 percent of all global desktop search traffic, that’s immense power.

While Google CEO Sundar Pichai swore before Congress in December 2018 that Google doesn’t make manual adjustments to the content it shows people, claiming that what’s instead responsible is a complex algorithm that takes into account the search result sites’ traffic, relevant terms searched, and other items, internal company documents leaked to the Daily Caller in April 2019 showed that humans do still manually prune the search engine’s blacklists across multiple features on the site.

One such blacklist, the XPA news blacklist, covers nearly every feature except for the 10 blue links and is governed in part by a “misrepresentation policy,” which is supposed to involve protecting users from sites that try to trick you into clicking on links on accident, but which was revealed by the Caller to include a host of conservative media outlets.

Google fist-in-glove with the Democrats

This is unsurprising, given Google’s extensive liberal leanings. Between 2004 and 2017, 90 percent of political donations from Google employees went to Democrats and in the 2018 and 2020 election cycles, Google’s parent holding company, Alphabet, Inc., gave 73 percent and 81 percent of its political contributions, respectively, to Democrats.

Several of Google’s top figures flocked to Clinton’s 2016 campaign as well, including Stephanie Hannon, who went from being Google’s director of product management for civic innovation and social impact to being the Clinton campaign’s Chief Technology Officer, and Osi Imeokparia, who was Google’s Product Management Director before becoming Clinton’s Chief Product Officer.

Eric Schmidt meets with Obama-era Defense Secretary Ash Carter in San Francisco, March 2, 2016. Tim D. Godbee | DoD

Eric Schmidt, then Alphabet’s Executive Chairman, helped organize and fund Civis Analytics and The Groundwork, two firms that crunched poll numbers and other data analytics for Team Clinton during the 2016 campaign.

Further, in the runup to the 2016 U.S. election, Google pushed its users towards Democratic candidate Hillary Clinton. Epstein’s research, published in March 2017, found that in the six months from May to November 2016, Google search results were biased towards Clinton in ways that “could not be accounted for by the bias in the search terms themselves,” Epstein wrote.

The popular YouTube pop culture channel SourceFed provided further evidence when it published a video demonstrating that Google’s suggested search completions favored Democrats and hurt Republicans. For example, typing “Hillary Clinton crim” into Google would yield the suggested autocomplete “Hillary Clinton crime bill 1994,” while other search engines like Yahoo and Bing would show “Hillary Clinton crimes.” Meanwhile, if you had typed “lying” into Google, the autocomplete suggestion would be “Lying Ted Cruz,” then-candidate Donald Trump’s derisive nickname for the Republican competitor. A comparable search of “Crooked Hillary,” Trump’s nickname for the former secretary of state, gave no similar suggestion.

Assembling Google News Initiative

In 2015, Google launched its own media pruning organs, First Draft and the Google News Lab, in conjunction with Facebook, Twitter, the George Soros-funded Open Society Foundations, the Omidyar-funded Knight Foundation, the Ford Foundation, and Craig Newmark Philanthropies, another billionaire philanthropist known for founding the website Craigslist. The two projects’ goals will by now sound familiar: aiming to coordinate “efforts between newsrooms, fact-checking organizations, and academic institutions to combat mis- and disinformation.”

That same year, Google launched its Digital News Innovation Fund, which was later folded into the much larger Google News Initiative along with Google News Lab. Through DNI, Google funneled €115 million to 447 European media outlets in every single European Union member state to “support high-quality journalism through technology and innovation.” However, with a majority of the funds going to media establishment staples like The Thomson Reuters Foundation and Telegraph Media Group, the move was widely interpreted as Google’s attempt to woo European media into a more friendly disposition.

That expanded to a much larger $300 million commitment in April 2018, when Google News Initiative was launched, and included a program to mass-train tens of thousands of fact-checkers to “monitor disinformation” in elections around the world. This kind of talk is really code-speak for what in the minds of security state thought police has become the perennial bugbear of Western civilization: “Russian meddling.”

Pentagon-Google cooperation

Alphabet’s Eric Schmidt, too, is connected to the U.S. security state as well as to the Democratic Party, again proving that a cross-party link is established where the material interests of the billionaire class are shared. A man who joined the Google team early-on in 2001, by 2011 Schmidt was able to step down from Google’s Chief Executive Officer to be the Executive Chairman of its Board of Directors with a $100 million equity award. He maintained that position through the 2015 restructuring of Google into the holding company Alphabet, Inc., stepping down in 2017 only to become chairman of the Pentagon’s Defense Innovation Board, an advisory committee to the Secretary of Defense.

However, he stayed on at Alphabet as its technical advisor, swearing to Defense One that “there’s a rule” that he wasn’t allowed to be briefed on Google’s ongoing bid for the massive JEDI cloud computing contract from the Pentagon. Google has in the past also worked directly with the Defense Department on the drone intel analysis AI dubbed “Project Maven,” as well as its present contract for the AI Next project with DARPA, the Google Earth project mentioned previously, and a host of other projects. The $10 billion JEDI contract was eventually given to Microsoft last month.

Likewise, Alphabet has been happy to oblige the State Department in conducting content purges similar to Twitter and Facebook, disabling accounts and channels it claims are “coordinated influence operations.” One incident in August 2019 saw YouTube disable 210 accounts for promoting content critical of the anti-Beijing protests in Hong Kong; the tech giant claimed on shaky evidence that the accounts were operating from mainland China.

Shane Huntley heads up Google’s Threat Analysis Group, which identified the “threat” and made the call to disable the accounts; before joining Google in 2010, he worked as a computer security research scientist for Australia’s Defence Science and Technology Organisation and then for the Australian government directly as a security software engineer. One of the so-called “Five Eyes” intelligence-sharing countries, Australian intelligence cooperates closely with New Zealand, the U.S., Canada and UK intelligence services, and has played a major role in forwarding the U.S.-led effort to undermine continued Chinese development.

We don’t need you to type at all…

“One of the things that eventually happens … is that we don’t need you to type at all because we know where you are,” Schmidt, Google’s then-CEO, said of the company in a 2010 interview with The Atlantic. “We know where you’ve been. We can more or less guess what you’re thinking about.” He later added, “One day we had a conversation where we figured we could just try to predict the stock market. And then we decided it was illegal. So we stopped doing that.”

On the internet, as in the realm of foreign policy, the U.S. security state is bipartisan in its bid to control the boundaries of acceptable behavior and thought, shepherding them by hook or crook into compliance.

The security state has sought to master this craft for more than half a century by sweeping through massive amounts of sociological data, tracking the attitudes, movements, and demographics of vast numbers of people in a bid to better map the tendency toward rebellion before it occurs. Tracking how billions of people navigate the internet, innocent of the knowledge they’re even being watched, has provided the security state with the greatest petri dish it could have asked for.

Facebook and Google have emerged as two of the leading access portals between users and the outside world, and far from the image of impartiality they project, this prominence had made them central figures in governing which information from that world we are able to access. The ties between these firms and the U.S. defense and intelligence spheres are myriad, not only harnessing for their own ends the high-tech R&D these firms develop for their own platforms, but also ensuring the manufacturing of consent over issues both at home and abroad that are favorable to the imperialist oligarchy and their security state.