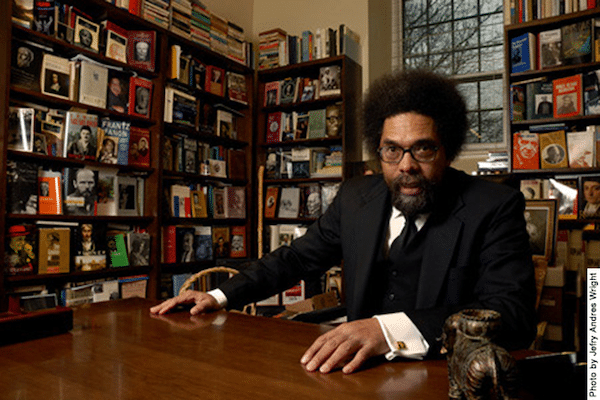

Teodros Kiros: I am privileged beyond description to attract the attention of one of the leading philosophers in the world today, Prof. Cornel West of Harvard University. Professor West has spoken at countless universities; his teaching positions have taken him from Princeton to Harvard to the seminary and back to Harvard again. Introducing him would take the entire hour. We are going to listen to the prolific contributions of a gifted orator, an extraordinary writer, and most importantly, the type of intellectual who walks the talk, who lives what he preaches. We are talking about a man who treats each and every human being whom he meets with absolute dignity and respect. I’ve been observing this professor for a few years now, and what is tantalizing about his character is that anybody who approaches him gets his maximum attention. He does not use power in order to gain more power. What he does is to use power to empower, to enable the marginalized, those who are not attended to, those who are not taken care of. After they speak to him he makes them beam with confidence and a sense of self. In short, he values them highly. Among his many books, I must first mention Prophesy Deliverance, which he published–like Fanon before him–at the age of 29, which in my judgement is the foundational work that put him on the philosophical landscape. This was followed by a series of books such as Prophetic Fragments, The Evasion of American Philosophy, Keeping Faith, Race Matters, then ten years later Democracy Matters. Today I have chosen two of his major books for discussion, Prophesy Deliverance, in which everything that came later is already presented in outline form, and then Race Matters, published ten years later (1993), which many consider to be his most important book.

Let’s begin with Prophesy Deliverance. What you do in this book is incredible. You draw from Martin Luther King, Malcolm X, then the famous Afro-centrist Professor James E. Cohn, and then the pragmatic tradition with which you were already familiar while you were doing PhD work at Princeton. Then you put them together and, much more importantly, you also do something extraordinary. You synthesize the ethical dimensions of Marxism with the radical dimensions of Christianity as we understand it and to my mind, Cornel, I do not exaggerate, you do it very successfully. It’s beautifully written, it is intelligible, it is accessible, it is just erudite and tantalizing to read, so why don’t we begin with that. What is your thesis in that book?

Cornel West: Yes, because going back now that was 1982, so that would be 37 years ago. What I was trying to do was to say that black people in the history of the United States have cultivated certain gifts in the face of unbelievable hatred and greed and domination and degradation, and those gifts are social as well as spiritual. They’re economic as well as existential, and they’re personal as well as political. I was trying to say, let’s tease out the indigenous practices of black people in the history of the American Empire, what kind of gifts given to the modern world, because we are a thoroughly modern people. We have been shaped and molded against the background of a very rich set of African civilizations, but on those slave ships on their way in the bowels of the new world as enslaved New World Africans, we have been forced to come up with various critiques, various forms of resistance, various forms of resilience, various forms of family, community. A lot of people talk about the music, the language, very important. Black musical tradition is in my eyes one of the greatest if not the greatest artistic and spiritual tradition in the modern world, but challenge what’s in that text. Let us take seriously the forms of catastrophe that black people have confronted and let us see what kind of creativity, what kinds of compassion we have been able to unleash in the world—fundamentally tied to a quest for freedom.We’re a hybrid people. We are an African people in a new world. We were shaped by legacies of Athens and Jerusalem. We’ve been shaped by scientific legacies of the European Enlightenment. We’ve been shaped by romantic traditions tied to the dignity of ordinary people, and when you look at all of those traditions filtered through the creative bricolage of black folk pulling from various elements and then dishing it out to the world, that’s what the Prophesy Deliverance was about.

Kiros: Incredible. And simultaneously… should I call you Cornel or-?

West: Oh, Brother West(laughter)

Kiros: Brother West, and simultaneously there was a loving critique of Martin Luther King.

West: Oh, absolutely.

Kiros: A loving critique of Malcom X, and then a celebration of Afro-Centricity. I’ve always been critical of Afro-Centricity. What I love about you is you don’t just fall in love with ideas, you decide to love them after you subject them to critical reason. This philosophical discipline runs throughout your work. It was even relevant, excitingly relevant when you spoke to Louis Farrakhan and you engaged him critically and lovingly to develop an analytically disciplined understanding of Jewishness. You did it by way of making him listen. Unlike his detractors, who attacked him, you did not attack him, you invited him to dig deep into the Quran, dig deep into the Bible and then develop a very complex understanding of Jews. Some are liberals, some are conservatives, and you cannot put them all into the same box. You bring in the same kind of discipline to King, to Malcolm X. I would like us to get deeper into that. Why the criticism of Farrakhan, Brother West?

West: Well first I’ll go back to my dear brother Minister Farrakhan, ‘cause I think there is a story that a lot of people don’t know. When Race Matters was published, there was a number of brothers in the nation who were highly critical of me and they would often follow me around on my lecture tour because I called Farrakhan anti-semitic, anti-Jewish. I would always invite them into the room, first and second rows if I could, to say please you all raise a question as soon as my lecture ends, ‘cause I want to have a dialogue. So I would go into ways in which there was certain characterization of “The Jews,” rather than conservative, moderate, left-wing, right-wing Jews. So any homogeneous characterization of a group could lend itself to not only a stereotype but a form of xenophobia, and so when I finally got a chance to meet the Minister at a leadership conference, he said “we must talk,” and I said, “I would love to talk,” but he was the kind one who invited me to Chicago. We were going to meet in the morning for about an hour or so, but we ended up talking non-stop for eight hours. Eight hours sustained of dialogue, and he even pulled out the Biblical text. He said “Well brother, look in the Gospel of John. We see a reference to ‘the Jews’.” I said John himself is wrong in using it in that way, but John himself was a Jew, so in that sense it was an intra-Jewish affair, so when he said “the Jews” he wasn’t talking about all Jews because he himself was disagreeing with the folk he’s talking about, and so I said this is one of the roots of anti-Jewish prejudice in the history of Christianity, and we know a good Muslim is always concerened about not just mercy towards others but staying in contact with the human, made in the image of Allah, and so the Minister and I would go back and forth. It was a beautiful thing, and we fought, we disagreed. He comes out of a black nationalist tradition, and I come out of a revolutionary Christian more Humanist tradition. In that sense, he would call it integration, and I would call it Humanist, and yet he himself had already made movements to a more Humanist orientation in terms of being open to Muslims of all colors. He was concerned even about various forms of patriarchy in the nation of Islam and had more and more women in high positions, so we enriched each other, and we grew to have a love and respect for one another. He was struggling with cancer. I discovered I had cancer and was given a few months to live, and so we talked and we prayed together, and so it was a matter of always trying to stay in contact with the humanity of anybody including my dear brother the Minister.

That’s true for any figure, it could be King, it could be Ella Baker, it could be Malcolm X, it could be Fanny Lou Hamer. All of us fall short of Truth capital “T.” And so we are all under a certain kind of critical judgment that we all ought to be open to because we are all fallible, we are all finite, as a Christian we are all fallen, and we all can grow and we all can develop. We all can mature, and the way you do that is through relationship. You learn and listen, you allow yourself to be challenged but you also challenge others. Absolutely, absolutely, and you try to be consistent about it, no matter what color, no matter what religious identity, national identity, sexual orientation, whatever it is, as a human being you have to be accountable, you have to be answerable and you have to be responsible.

Kiros: Incredible. And the very title of the book, Prophetic Deliverance, is extraordinary. Let us unpack it philosophically. What is the idea of Prophetic Deliverance as a philosophical concept? What kind of umbrella is it, metaphorically speaking and assuming the difference of the dignity, the freedom and what you call the intrinsic, inherent rights that as individuals outside of the spectrum of race, class and gender have? I like the way you have juxtaposed these two terms, the “Prophetic” dimension and the idea of “Deliverance.”

West: Well some of that is actually attributable to one of the great ministers, pastors, preachers in the early 21st century, James Forbes, he helped me come up with that title. I remember he said, “I’ve been reading parts of your texts and you talk about Prophesy Deliverance!”

Kiros: That’s right!

West: I said “Oh, wow, I see what you’re saying.” Now it seems I find such a profoundly religious character to it, but there are secular modes that can be attributed as well. We can go back to the great work of the prophets by the inimitable Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel, who defines the prophet as “he or she who has a hypersensitivity to the suffering of others, especially the suffering of the vulnerable.” And it goes back to the prophetic Judaisim which says that to be human is to spread “Hesed,” which is steadfast love, loving kindness, to the orphan, the widow, the fatherless, the motherless. Micah 6:8 said, “do justly, love mercy, walk humbly with thy God,” and when you look at the history of prophetic voices it could be those under slavery in Egypt, it could be modern working people in capitalist society, it could be contemporary poor people in a society in which the top one percent is driven by greed, indifference or callousness, it could be Roma in Europe, so-called Gypsies, it could be Dalits in India, so called “Untouchables,” it could be peasants in Ethiopia coming to terms with a professional elite that is not speaking to their interests in a serious way. Any hypersensitivity to the suffering of others is a prophetic moment. It’s very interesting, in the last paragraph of Georg Lukács’s great essay, “What is Orthodox Marxism?” (March 1918), he says, “Orthodox Marxism is no guardian of tradition.” It is expressed in the prophet-driven utterances of the present connected to the overall process of history as a totality. Now he’s using again Marx’s language.

Marx himself, C.L.R. James himself, Angela Davis herself, all of them secular thinkers, still have prophetic dimensions to what they’re doing. Now deliverance of course has to do both with an attempt to facilitate oppressed people coming up with ways theoretically, practically of overcoming their oppression and therefore involved in a certain kind of deliverence on their own, but in the biblical sense, deliverance also has to do with divine powers, with grace and so forth, so it can go a number of different ways. But deliverance was really an attempt to accent what we would call in the 20th and 21st centuries “Utopian Energies.”

Kiros: Incredible. A la Ernst Bloch.

West: That’s exactly it. And the Principle of Hope, absolutely.

Kiros: Incredible, so there is a family resemblance —

West: Absolutely.

Kiros: Particularly when you secularize it as you did. So now, I want to move to Race Matters. And there of course I’m going to need five hours since you promised me the opportunity to interview you again!

(laughter)

So let’s touch the surface. I want to concentrate on two central concepts. Let’s first talk about the philosophical studies of the idea of nihilism. Let’s ground it… as you do and then we’re going to move to a special instance of it, which is attributable I think to hypersensitive empathy with the suffering of black people globally. Because in order to understand their condition, you’ve also coined another term that captures their predicament, which you call “Black Nihilism.” So let’s begin with a major concept and then look at the special instance. How should we understand Nihilism?

West: Well, this is a very powerful question, brother, and I’m rarely asked this question so I appreciate that, I really do, but for me in the modern context, the concept of Nihilism is first articulated most explicitly in the history of the Russian Intelligentsia. Remember Bazarov in Fathers and Sons by the great Ivan Turgenev is an exemplar of Nihilism. In his view a nihilist is somebody who accepts the authority of science, who accepts the materialist conception of the world, and because science cannot give us values, it can give us ways of understanding the world in order to predict the future in light of the past in order to manipulate the world and through technological instrumentalities, dominate the world, squeeze out from the world what it can, treat nature as an ‘it,’ an object to be manipulated and yet unable to provide structures of meaning–unable to address issues of love, intimacy, community, values, and virtues. Bazarov of course reached his end in that great novel, but what Turgenev was getting at was the various ways in which the modern world makes it very difficult for us to gain access to modes of meaning.

For me, Anton Chekhov is in many ways the great literary artist of European modernity. Shakespeare begins, Chekhov is at the end, postmodern is a different moment. What is it about Chekhov? Well, Chekhov is dealing with a certain kind of Nihilism, but he’s trying to argue that the best we can do is to persevere with courage, the best we can do is have stamina, the best we can do is have a strength acknowledging that whatever structures of meaning we have are contingent, they’re changeable, they’re variable. Chekhov has read Schopenhauer and Nietzsche. Schopenhauer and Nietzsche are the two great 19th-century figures in Europe who shatter the structures of meaning and end up profiling pessimism in the case of Schopenhauer or wrestling with Nihilism in the case of Nietzsche. Nietzsche has a notion of passive Nihilism in which you’re resigned to nothingness, active Nihilism in which you engage in what he calls transvaluation of values. And so through creativity you attempt to call into question the values in place. What is the value of truth? What is the value of beauty? What is the value of goodness? What is the value of God? What are the ways in which various revolts in the past have transvalued those values and how can we look at what they’ve done and come up with new ways in which we can overcome what is in place? So on the one hand you got a moment, the Russians in the early part of the 19th century, you got Chekhov who dies in 1904 mediated with Schopenhauer and Nietzsche, then I come to Black –

Kiros: Nihilism

West: Predicament

Kiros: Incredible

West: How have these magnificent New World Africans come to terms with their sense of meaning being shattered by slave ships, slave auctions, plantations, lynching trees, various bombardments telling them they are less beautiful, less intelligent, less moral, trying to convince them they have the wrong hips and lips and noses and skin texture and hair texture and skin color, the bombardment of white supremacy that’s trying to pull the rug from under any quest for meaning let alone the quest for freedom? So, in my essay I was arguing why on one hand we have to come to terms with the market forces of a capitalist society. What are the ways in which commodification, commercialization, and marketization have attempted to soak the very souls of black folk and make us think that somehow we are less human, less valuable and unable to generate new forms of meaning? So, you have an economic dimension and philosophic dimension. There’s a rich philosophical tradition, but the circumstances change. Russia, 1860s, different than Chicago, New York, Detroit, Atlanta, L.A. in the 1990s when I wrote that essay on Nihilism.

Kiros: And you know, Cornel, what is very unsettling about some of the mis-readers of Race Matters–and there are quite a few of them–is that some are simply jealous. They don’t understand the argument. What you are trying to do in that work, as you just said, is to bring in the existential dimension…

West: That’s right, that’s right.

Kiros: With the Marxist dimension.

West: That’s right.

Kiros: The critique is a blend of the critical theory of society… the political economy of Marx, particularly the theory of commodification —

West: Absolutely.

Kiros: Extraction of…value, and the way that this profit motive literally distorts the life chances of black people thereby contributing to their alienated sense of self, giving them this impression that life is meaningless, brutal, and short and here comes professor West who is contending “No, it is not about the shortness, the nastiness, the brutishness of life. It’s about the systematic penetration of capital in the form of the extraction of surplus value, literally distorting what Julius Wilson calls the life chances of Blacks.”

West: That’s right, that’s exactly right, you read it in a way I would have liked people to have read it, absolutely.

Kiros: But it is glaringly present for you that meaninglessness is not a natural condition; it is a condition that appears to be natural only because it is penetrated by capital, and those who do not know that the extraction of surplus value is simply a historical product have a tendency to think that meaninglessness and nothingness are natural to the human condition, and you are contending “No they are not. Black nihilism is grounded in what capital continues to do to the life chances of blacks.”

West: That is exactly right. Very much so. When I was writing that, I had three intellectual sources in mind. One was Georg Simmel’s philosophy of money and how objectification mediated through currency and market exchange creates these ‘I, it’ relations, in the language of Martin Buber. And it’s very difficult to get an ‘I, Thou’ relation, human to human, soul to soul, face to face, I to I, subject to subject. I had in mind certainly Karl Marx on commodification. That has been one of the fundamental sources of my own intellectual formation, and it goes from Marx to Lukács because Lukács’s History and Class Consciousness has always been at the center of so much of what I do. That’s why Fred Jameson as a disciple of Lukács has meant so much to me, Stanley Aronowitz as a disciple of Lukács has meant so much to me, but also Weber’s notion of rationalization which is a form of bureaucratizing the world with impersonal rules and regulations so that you’re always detached and distanced from certain aspects of yourself. You’re playing a role, you’re wearing a mask, and in Weber’s two great essays on science as a vocation and politics as a vocation, the ethics of conviction always clash. You’re in institutions, you have various kinds of duties and obligations relative to the rules and regulations of those institutions. Weber called his project “Being locked in the iron cage.” Marx called his project “Being locked in structures of unfreedom,” and Simmel and his project meaning you’re alien to yourself, you’re a stranger to your own self. You get all three of those then shot through black life in the largest empire in the history of the world, the U.S. empire deeply capitalist in its culture but also tied to claims of innocence.

James Baldwin used to say ‘innocence itself is the crime’. You think you’re innocent and you’ve already stolen the land of indigenous people, enslaved these Africans, exploited various workers of all colors, confined women to domestic households, debased and demonized gays and lesbians and trans and so forth, then like any other empire, like any other nation as Walter Benjamin would say “You’re tied to some form of barbarism.” And if you think you’re innocent and in denial about your own barbarism, then there’s a good chance you’re living in America, because America is unique among empires to believe it moves from perceived innocence to corruption without a mediating stage of maturity. We as an empire have grown powerful and rich, but we’ve never really grown up. We’ve had some great figures who’ve tried to teach us to grow up, Melville and Whitman and Martin Luther King and Malcolm X… Stephen Sondheim, some of the great prophetic figures in the history of the American empire, but as a whole though, we’re still Peter Pan-like, we just don’t want to grow up.

West: Well I look forward to our next conversation!

Kiros: Thank you very very much.

West: Thank you!

Notes

For more info on Dr. West, see his website.

Dr. Teodros Kiros is a professor of philosophy at Berklee.

Thanks to Prof. Victor Wallis (Berklee College) for his help preparing the written text of this interview.