Economic inequality in the United States and around the world is now so obscene, and has convinced more and more people to do something about it, that the business press has initiated a campaign to deny its very existence.

They and the folks they represent are losing the battle of public opinion. And they’ve decided to do something about it.

First up was the Economist, the “newspaper” of record for liberal capitalism [ht: sk], claiming that new research undermines the pillars of the seemingly universal belief that “inequality has risen in the rich world.” Yes, as I have documented from the very beginning on this blog (e.g., here, here, and here), there are plenty of mainstream economists who have attempted to prove that inequality isn’t really a problem—either because it doesn’t really exist or, if it does, it’s not something we can or should do much about. And so the Economist managed to find pieces of research that call into question some of the key pillars of the inequality argument—that the gap between the top 1 percent and everyone else is growing, the middle-class is shrinking, capital is gaining at the expense of labor, and wealth inequality is soaring.

I won’t waste readers’ time repeating the arguments I’ve made on all four of those points over the past decade. You can use the search function at the top of the page to see what I and others have written on these issues—or look at the latest report from the Congressional Budget Office, which I discuss below.

What’s more interesting is where the Economist wants to take the discussion—away from wealth taxes (of the sort being proposed by Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren) and toward the sorts of policies that, while they won’t lessen the degree of inequality, conform to the Economist‘s fantasy of liberal capitalism. Thus, they propose more building (so that young workers can afford housing), antitrust regulation (as if capitalism didn’t have an inherent tendency toward monopoly), less regulation of high-income professions (to create more competition for those high-paying jobs), and fewer restrictions on immigration (but only for “high-skilled” workers).

That’s the Economist’s derisory attempt to minimize the existence of inequality (against most of the available evidence and widespread belief) and to devise some tiny tweaks in existing economic arrangements (and avoid more serious efforts to lessen the degree of inequality).

The Wall Street Journal has also decided to confront the growing campaign against economic inequality—by attempting to show that Donald Trump’s administration has done more to decrease inequality than Barack Obama’s, by promoting economic growth through deregulation and increased business investment. Now, it’s true, Obama oversaw a bailout of Wall Street and a return (after a brief hiatus in 2009) to the same unequalizing trends that predated the Second Great Depression. So, that’s a very low bar to surpass.

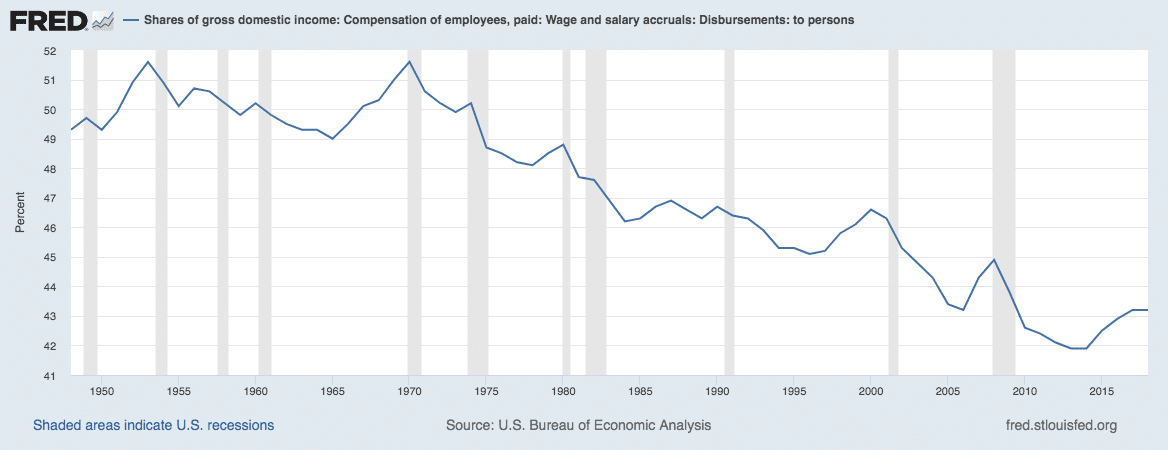

And even though the wages of low-income workers have been rising at a faster rate in recent quarters (the supposedly “happy wages of a growing economy”), it is still the case that the wage share of national income (as seen in the chart above) is still less than what it was in 2008 (when it was 44.9, compared to 43.2 in 2018) and far below its postwar peak in 1970 (at 51.6).

To rely on continued growth to solve the problem of inequality is simply a pipe dream, which is even less convincing than the castle in the air invented by the business press on the other side of the pond.

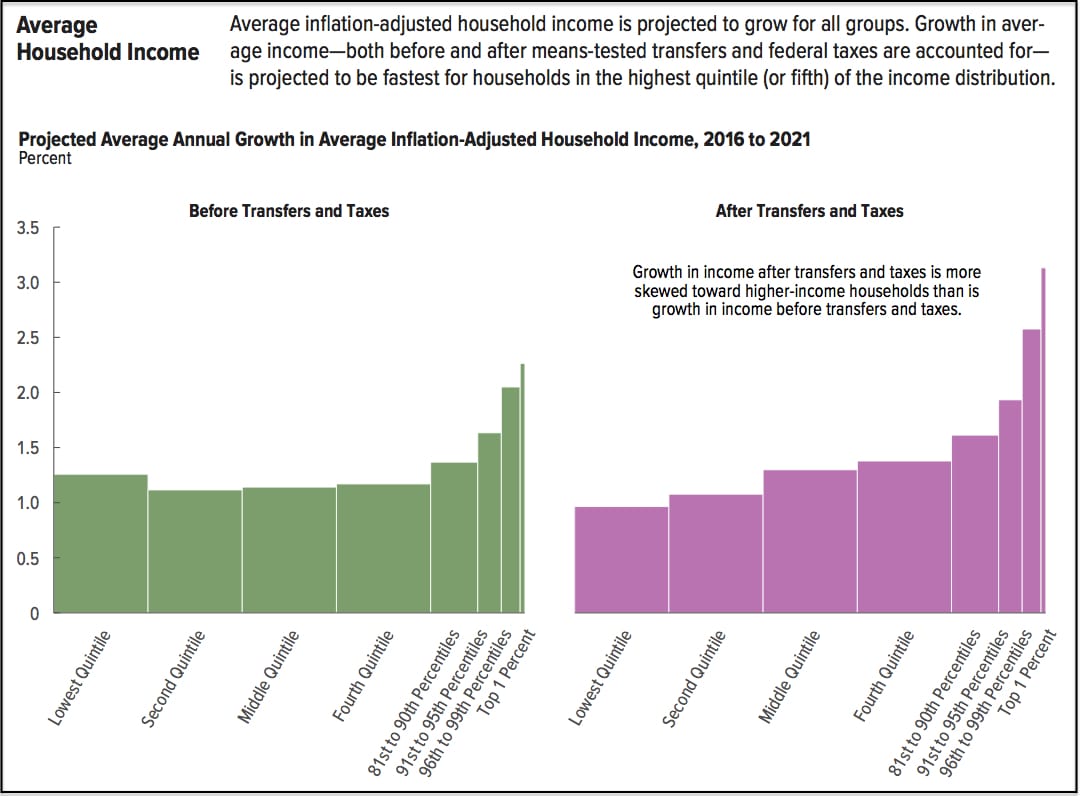

The fact is, the Congressional Budget Office [pdf] projects that income in the United States—both before and after transfers and taxes—will be more unevenly distributed in 2021 than it was in 2016. That’s because, even though average incomes for the bottom four quintiles are expected to grow, incomes for the top quintile (and especially for the top 1 percent) are expected to grow even faster.

Thus, for example, since 1979, while the average incomes of the middle three quintiles are expected to grow (after transfers and taxes) by a total of 57 percent, the incomes of those in the top 1 percent are projected to increase by a whopping 281 percent by 2021.

There’s no other way around it: inequality in the United States is obscene, and something—much more than minor regulations and continued growth—needs to be done to overcome it.

As it turns out, Americans are fully aware of the problem. For example, according to Gallup, the overall opinion of capitalism held by young adults (both Millennials and Gen Zers) has deteriorated to the point that capitalism and socialism are tied in popularity.

And a new Reuters/Ipsos poll finds that nearly two-thirds of respondents agree that the very rich should pay more.*

Among the 4,441 respondents to the poll, 64% strongly or somewhat agreed that “the very rich should contribute an extra share of their total wealth each year to support public programs”–the essence of a wealth tax. Results were similar across gender, race and household income. While support among Democrats was stronger, at 77%, a majority of Republicans, 53%, also agreed with the idea.

Moreover, when asked in the poll if “the very rich should be allowed to keep the money they have, even if that means increasing inequality,” 54 percent of respondents disagreed.

That’s the reason the Economist and the Wall Street Journal have decided to launch their campaign about inequality—to attempt to undermine the widespread belief that inequality is growing and, even more, to challenge any and all efforts to actually do something to create a more equal economy and society.

Such a campaign may satisfy their readers, at least in the short run, but the problem itself will remain. This election year, I expect the growing gap between the tiny group at the top and everyone else to overshadow their shabby efforts and culminate in a movement they simply won’t be able to contain.

* Ironically, another recent attempt to undermine the Sanders-Warren proposals of new, higher wealth taxes actually serves to reinforce how extreme wealth inequality is in the United States. While admitting that “only a small segment of the population would be subject to the top rate,” the American Action Forum’s Douglas Holtz-Eakin and Gordon Gray [pdf] can only conclude that the taxes would have “broad impacts” only because the wealth holdings of that group “constitute a significant share of the investable wealth in the economy.”