Dear Friends,

For Ernesto Cardenal (1925-2020), who has gone to hand out clandestine pamphlets in the sky.

Greetings from the desk of the Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research.

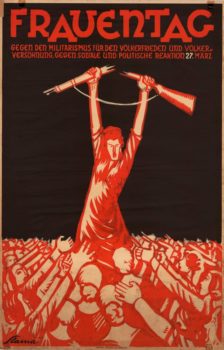

On 8 March 1917 (23 February by the old Julian calendar), a hundred women in the textile factories in Petrograd decided to go on strike; they went amongst the other factories and called their fellow workers onto the streets. Before long, around 200,000 workers–led by the women–marched through the streets. ‘Down with war’, they cried, and ‘no bread, no work’. This strike set in motion a cascade of protests which eventually broke the Tsarist state and inaugurated the Russian Revolution.

Seven years before the start of the Russian Revolution, the German Marxist Clara Zetkin proposed to the 2nd International Conference of Socialist Women in Copenhagen (Denmark) that an International Women’s Day be held each year. They chose 8 March to commemorate the ‘March Revolution’ of 1848 in Europe, when the monarchies were forced to nominally accept universal suffrage. From 1911 onwards, it was socialist women who held rallies and demonstrations on 8 March as part of their campaign first for the franchise, and then–after 1914–to end the war. They faced terrible repression, harshest perhaps in the Tsarist empire. It did not stop them.

When the entire editorial board of Rabotnitsa (‘The Woman Worker’) was arrested before the 8 March 1914 protest, Anna Elizarova–Lenin’s sister–hastily gathered some comrades, produced the paper, and then saw to the distribution of twelve thousand copies on that day. For these socialist women, International Women’s Day was a powerful rebuke against the brutality of the war and the indignity of patriarchy. In the midst of the events of 1917, Ekaterina Pavlovna Tarasova, a Bolshevik organiser, remembers that a woman worker told her, ‘We who were nothing and have become everything, shall construct a new and better world’.

In 1920, the Bolshevik leader Alexandra Kollontai wrote that women in the Soviet Republic had rights and the vote, but that ‘life itself has not absolutely changed. We are only in the process of struggling for communism and we are surrounded by the world we have inherited from the dark and repressive past’. What was ahead was the struggle. The next year, the 2nd International Congress of Communist Women fixed 8 March as the date for International Women’s Day. It would eventually be adopted–due to the work of the Women’s International Democratic Federation–by the United Nations in 1977.

The origins of the day lie in people like Nina Agadzhanova, the Bolshevik member of the editorial board of Rabotnitsa, who later wrote the splendid film Battleship Potemkin; she leapt before a tramcar on 8 March 1917, grabbed the keys from the driver, and declared that the city of Petrograd was on strike.

To develop the seam of socialist feminist thought, our team at Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research will release a series of studies on the history of women in our struggles. The opening booklet, published this week to commemorate 8 March, lays the groundwork for this series of texts. It offers an analysis of the conditions for women in our time and of struggles led by women against the regimes of austerity and war. There are detailed analyses from Latin America, India, and South Africa not only of the perilous situation for society but of the organisational forms of struggle that have developed in response to these adverse conditions. As our team writes, ‘we are particularly interested in highlighting the progressive, feminist, and mass resistance processes in the Global South and in identifying the key characteristics of the struggles of our time, inspired by the legacy of women in struggle throughout the 20th century’. Do read this text carefully and share it in your movements and in your networks. Other texts in this series will appear over the coming months.

To develop the seam of socialist feminist thought, our team at Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research will release a series of studies on the history of women in our struggles. The opening booklet, published this week to commemorate 8 March, lays the groundwork for this series of texts. It offers an analysis of the conditions for women in our time and of struggles led by women against the regimes of austerity and war. There are detailed analyses from Latin America, India, and South Africa not only of the perilous situation for society but of the organisational forms of struggle that have developed in response to these adverse conditions. As our team writes, ‘we are particularly interested in highlighting the progressive, feminist, and mass resistance processes in the Global South and in identifying the key characteristics of the struggles of our time, inspired by the legacy of women in struggle throughout the 20th century’. Do read this text carefully and share it in your movements and in your networks. Other texts in this series will appear over the coming months.

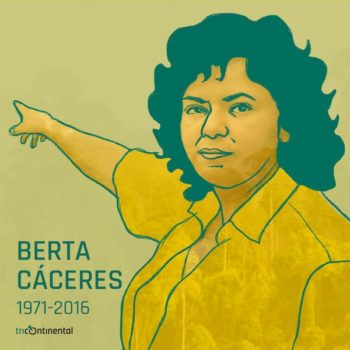

Four years ago, on 2 March 2016, hired hitmen assassinated Berta Cáceres, who was one of the leaders of the Civic Council of Popular and Indigenous Organizations of Honduras (COPINH). Cáceres and COPINH fought against the building of a dam on the Gualcarque River in western Honduras. The company that was building the dam–Desarrollos Energéticos Sociedad Anónima (DESA)–fought her using the full power of the Honduran state. Honduran police and military guarded the site, and it was former Honduran armed forces members who assassinated Cáceres. Evidence at the trial of these men showed the deep complicity of the Honduran state as a whole, including of the current government led by Juan Orlando Hernández. In 2009, the U.S. government–along with the Honduran oligarchy–overthrew the left-leaning government of Manuel Zelaya; in his place, they put the preferred instruments of the oligarchy and the United States, namely the far-right National Party of people like Hernández. Berta Cáceres was killed not only by these hitmen, but by the detritus of a coup d’état that established a government of impunity.

I recently spoke to Berta Cáceres’ daughter Bertha Zúniga Cáceres, who told me that the past four years have been difficult for her personally and for COPINH, which she now coordinates. The hitmen have been sentenced to prison, but the authors of the assassination–the owners of DESA and the men in the state apparatus–have not been investigated or charged. But this is not where she is putting her attention. With the weight of the socialist feminist tradition on her shoulders, Zúniga Cáceres is focused on the welcome mat that the far-right government has placed for transnational corporations to extract resources and undermine the rights of the Honduran people. There needs to be a ‘refoundation of Honduras’, she told me.

I recently spoke to Berta Cáceres’ daughter Bertha Zúniga Cáceres, who told me that the past four years have been difficult for her personally and for COPINH, which she now coordinates. The hitmen have been sentenced to prison, but the authors of the assassination–the owners of DESA and the men in the state apparatus–have not been investigated or charged. But this is not where she is putting her attention. With the weight of the socialist feminist tradition on her shoulders, Zúniga Cáceres is focused on the welcome mat that the far-right government has placed for transnational corporations to extract resources and undermine the rights of the Honduran people. There needs to be a ‘refoundation of Honduras’, she told me.

The assassination of Berta Cáceres came two years after gunmen burst into the home of Thuli Ndlovu, a leader of South Africa’s Abahlali baseMjondolo. The local political leadership in KwaNdengezi had interests in the development of housing; Ndlovu and Abahlali had the audacity to organise working women into a political organisation to confront their economic and political power. It is for this reason that Ndlovu was assassinated. The next day, Abahlali released a powerful statement on the murder. ‘Our movement is shocked, but not surprised’, they wrote. ‘We have accepted that some of us will die in this struggle. … We are facing a war. The struggle for land and dignity continues’.

There are so many names to be added to the list that includes Cáceres and Ndlovu.

Honduran president Hernández entered his second term in 2018 following allegations of election fraud that evoked mass protests across the country; Hernández responded with tear gas and live fire. Nobody in the office of the Organisation of American States (OAS) raised an eyebrow. Hernández, for all the investigations against him about narco-trafficking, is favoured by the United States government. This whole business of election fraud is now deeply political, with organisations like the OAS weaponised to undermine left-leaning governments. A new study by two scholars from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) shows that there was no fraud in the Bolivian elections of 2019; the OAS ‘preliminary’ report on that election alleged fraud, which was used by both the U.S. government and the Bolivian oligarchy to overthrow the government of Evo Morales Ayma. Morales is in exile in Argentina, the far right is in control in Bolivia, and Washington has sent down its USAID teams to ‘monitor’ the elections (for a briefing on the elections in Bolivia, read our Red Alert no. 6). The conditions for the 3 May elections are terrible, with violence against the party of Morales, Movement for Socialism (MAS), structured into the behaviour of the state apparatus. A U.S. government-funded official who helped sanctify the elections in Honduras–Salvador Romero–is now in charge of the elections in Bolivia.

On 23 February 2020, the legions of the far right, egged on by elected officials of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), went on a rampage against the Muslim residents of North East Delhi. So far, almost fifty people have been killed and thousands have been injured and displaced. The men marched through the streets chanting violent slogans, their purpose to intimidate Muslims by beating and killing people and by burning their homes. The Delhi Police, controlled by the government of Prime Minister Narendra Modi, stood by, complicit in this terrible violence provoked by the BJP’s discriminatory citizenship act.

Meanwhile, in Kerala, where the Left Democratic Front is in power, the government–through its LIFE Mission–has just inaugurated 200,000 homes for the homeless. Kerala Chief Minister and Communist leader Pinarayi Vijayan said that his government turned over the homes to people without asking the names of their caste, religion, or citizenship. They only asked, he said, ‘if they had a home to call their own’.

One side of history burns houses; another side builds them.

From 5-9 March, three thousand militants will attend the First National Meeting of Landless Women of the Landless Workers’ Movement (MST) in Brasília. They will be there to underline that they are women in struggle and that they are ‘sowing the seeds of resistance’. On the last day of their meeting, women in Mexico will go on strike. Their hashtag is #UnDíaSinNosotras–a Day Without Us.

There is a straight line from the Bolshevik Nina Agadzhanova to the Mexican women who will stop their own tramcars and march down their own streets.

Warmly, Vijay.