Dear Friends,

Greetings from the desk of the Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research.

Burkina Faso, in the Sahel region of the African continent, has been struck hard by the global pandemic; officially reported deaths from COVID-19 are second only to Algeria in Africa. In the past sixteen months, nearly 840,000 people out of twenty million have been displaced by conflict and drought; in March alone, 60,000 people were forced from their homes. Last year, the United Nations calculated that the number of Burkinabè residents who had little access to food was 680,000; this year, the UN estimates that the number will rise to 2.1 million. Conflict over resources and ideology had already greatly strained the region, where the climate catastrophe-generated desiccation of the Sahel has produced a serious agrarian crisis. No wonder that Xavier Creach, the Sahel coordinator of United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) recently said:

Local communities have demonstrated remarkable generosity, but cannot cope anymore. National capacities are overwhelmed. The approaching lean season, coupled with the armed conflict and the COVID-19, will generate further dramatic situations and displacements of populations. The clock is ticking; we have little time left.

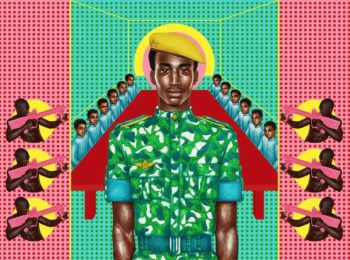

How the world has deteriorated. In 1984, Burkina Faso’s Marxist leader Thomas Sankara came to the United Nations and spoke about the importance of eradicating hunger. He said that each person in his country deserved–at a minimum–two meals a day and clean water. To that end, Sankara’s socialist government drove an agenda of agrarian reform, which included land redistribution and tree planting to combat desiccation; he began the un village, un bosquet (‘one village, one grove’) project which resulted in the planting of ten million trees over fifteen months. ‘We must produce more’, he said, without rely upon foreign aid and the import of food ‘because it is natural that he who feeds you also imposes his will’. ‘Our stomachs will make themselves heard’, Sankara said as his policies eradicated hunger in Burkina Faso, as reported by the former UN Special Rapporteur on the right to food Jean Ziegler. Sankara was assassinated for these policies in 1987, and Burkina Faso was turned into a ruin of the great dream of emancipation.

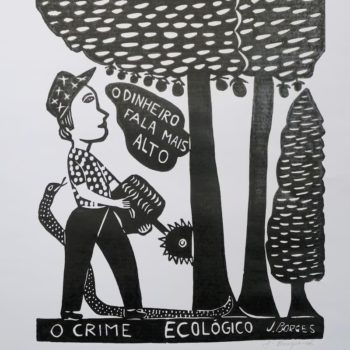

In 1971, the Brazilian singer Zélia Barbosa released her album Brazil: Songs of Protest, in which she covers a song by Edu Lobo and Ruy Guerra from 1964:

without a country in which to live, a field to plant, a love to cherish or a voice to sing, one is dead.

In Brazil and in many parts of the world, the creation of massive feudal landholdings (‘latifundios’)–and now corporate farms–has taken the means of production and the mechanisms for survival out of the hands of hundreds of millions of peasants around the world. Once dispossessed of their land, they are forced to sell their labour power to industrial and agricultural factories. Detached from their roots in the soil, agricultural and industrial workers in the Global South became footloose labour as they walked from field to factory and from factory to field in an endless spiral in search of work.

Harsh exploitation and land hunger combined to produce political movements across the world for land reform and for unionisation. In Brazil, these developments led to the creation of the Landless Workers Movement (MST) in 1984, which has occupied land, built settlements, and created a culture of cooperation, solidarity, and cooperatives as instruments to further the struggle of agricultural workers and the landless poor. This struggle has inspired landless workers across the world to reclaim their right to land–from Argentina to Haiti to Zimbabwe. For the MST, the struggle has been rooted in the land, but it has developed outwards politically to become a struggle against social oppression of all kinds–such as racism, patriarchy, homophobia–and for total social transformation. The struggle is an old companion of Afro-Brazilians, who led the fight against the system of slavery and are now so much a part of this fight over land and over the defence of nature; that history of struggle redeems humanity from its worst incarnation.

Our Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research dossier no. 27–Popular Agrarian Reform and the Struggle for Land in Brazil–explores the long history of land struggles in Brazil and offers a clear-sighted introduction to the ideas and work of the MST. The second part of the dossier describes life and work at the thirty-year-old Conquista na Fronteira (‘Conquest at the Border’) settlement in the municipality of Dionísio Cerqueira in the state of Santa Catarina. Irma Brunetto, who has lived in the settlement from its origin, guides us into the way it is organised, how people live there, how they cultivate the land cooperatively, how their children study, and how they tend to their health. ‘In a society that is as individualistic as ours, we swim against the tide’, says Irma. But she knows that the cooperative method is necessary for a planet wracked by conflict and hunger, by the failure of the bourgeois order.

Oxfam and the United Nations released a study on April 8, which showed that there is the possibility of a 20% income or consumption contraction due to COVID-19; this means that the number of those living in poverty will likely increase by between 420 million and 580 million. This will be the first time in thirty years that the numbers of those in poverty have increased, and the first time that the increase will have taken place so rapidly. The impact on rural areas will be stark. The bourgeois order has no answer to the suffering; in stark contrast, organisations like the MST–rooted in the socialist horizon–have already been experimenting for the future.

Oxfam and the United Nations released a study on April 8, which showed that there is the possibility of a 20% income or consumption contraction due to COVID-19; this means that the number of those living in poverty will likely increase by between 420 million and 580 million. This will be the first time in thirty years that the numbers of those in poverty have increased, and the first time that the increase will have taken place so rapidly. The impact on rural areas will be stark. The bourgeois order has no answer to the suffering; in stark contrast, organisations like the MST–rooted in the socialist horizon–have already been experimenting for the future.

João Pedro Stédile is a member of the national leadership of the MST. I spoke to him this week about how Brazil is dealing with the CoronaShock, and about the imperative of agrarian reform.

What is your quick assessment of why the Brazilian ruling class refuses to address the fact of land hunger in the country?

Brazil is the country with the highest concentration of land in the world. This is rooted in our colonial past; for 400 years, land was owned by the monarchy, who relied on the labour of slaves, indigenous peoples, and Africans. Our dominant class is essentially still based on slavery today; it considers workers to be merely objects to be exploited.

We missed the opportunity to enact agrarian reform when slavery was abolished in 1888, as occurred in other countries such as the United States, Haiti, and other countries in Latin America. Then we missed the opportunity again when we entered into industrial capitalism in the 20th century and did not build a market for domestic consumption. We again missed the opportunity in the 1960s, when even the Kennedy administration in the United States–scared by the Cuban Revolution–defended agrarian reform as a way to contain the advance of revolutions on the continent.

In Brazil, economic power and the dominant class are made up of large landowners, industrial capital, banks, and transnational agricultural corporations, all of which merge and act together; these actors prefer a model that concentrates agribusiness over one that enables agrarian reform.

In Brazil, economic power and the dominant class are made up of large landowners, industrial capital, banks, and transnational agricultural corporations, all of which merge and act together; these actors prefer a model that concentrates agribusiness over one that enables agrarian reform.

Is Brazil ready for a new historic project against the impasse of neo-fascism? Will Bolsonaro’s decadent response to Corona make a dent in neo-fascism?

Brazilian society is immersed in its biggest crisis in history. We have been in the throes of a deep economic crisis since 2014, which generated a social crisis rife with unemployment, precarization, and a greater dependence on finance capital, which then developed into a political crisis with the coup against Dilma, followed by the election of a neofascist government.

The outbreak of the coronavirus has deepened this crisis in every way, which has been made worse from a social perspective, since–as we have seen in other countries–the only way that we can confront the virus is with a strong government, with people’s organisations and leadership at the forefront.

The neofascist government is the complete opposite of this, representing a mere 8% of fanatic followers, neofascists, Pentecostals, and a lumpen bourgeoisie. I believe that the coronavirus is going to help us lift the awareness of the people and divide the bourgeoisie and the middle class and that–when we return to the streets–we will overthrow the fascist government.

The neofascist government is demoralized. It has been left with merely following the ideology of the Trump administration; they are both on the same sinking ship. The United States Empire will also be defeated by this crisis.

What will make the non-rural population accept the imperative of agrarian reform?

The economic, social, political, and coronavirus crisis are helping us show the general population–85% of whom live in cities–that we need to organise a new anti-neoliberal, anti-imperialist economic model. We hope that we can build new paradigms of social organisation.

One of these paradigms is that–to ensure the health of the entire population–we need to have healthy food. Only small farmers and peasants can produce healthy food; agribusiness doesn’t produce health food–it produces commodities and is exclusively interested in profits. This is anti-social.

In the near future, we will have better conditions to explain to the people that new agrarian reform will not only redistribute large landed estates give work to the peasants. This new type of agrarian reform is based on new paradigms: producing healthy food for all based on an agroecological model that is in harmony with nature and that protects water and fights against inequalities and environmental crises such as climate change. This new agrarian reform will also produce food using agroindustry and scientific knowledge to support our food sovereignty. In other words, each region or territory will produce its own food, avoiding dependence upon international trade with transnational corporations. We will carry out international trade of food only with the surplus that is produced after ensuring that all of our people are fed. We will value local cuisine and the culture of our people. We will guarantee access to education for the entire population, including in the countryside. This popular agrarian reform will benefit not only the peasantry but the entire population–much of which is already living in cities.

Such is the agenda that looks ahead and does not marinate human anxiety in hatred.

Of such a vision of the world, the MST leader and poet Ademar Bogo offers us this lovely poem, It Is Time to Harvest:

There are moments in history

in which all victories

seem to slip away from us.

But it is those who do not get discouraged who win

and seek in their self-worth

the strength to be persistent.Time passes slowly, but with it passes

the glory of the emperor.

Those who have hands to build

will have to get up and decide on

the day that they will bury the painand rise from everywhere

to say that it is time to harvest

everything that was planted.

People are like the water from the sea:

even as it moves slowly,

it shows through its swaying

that it can never be bent.We watered the desert of conscience

and a new being was born;

it is time to go ahead comrade;

you are the fighter that history has given us.

It is time to discard the hierarchies and miseries that we have inherited from the past and build the possible–and necessary–utopias of the future. It is this future that needs cultivation.

Warmly, Vijay.