Early evidence of the crisis in the developed world induced by the COVID-19 pandemic is trickling in. One set of numbers provides the first estimates of GDP growth in the first quarter of 2020, which includes the period when lockdowns suddenly stopped economic activity. This relates to the U.S. and the Eurozone, which are among the epicentres of the pandemic in the group of OECD countries.

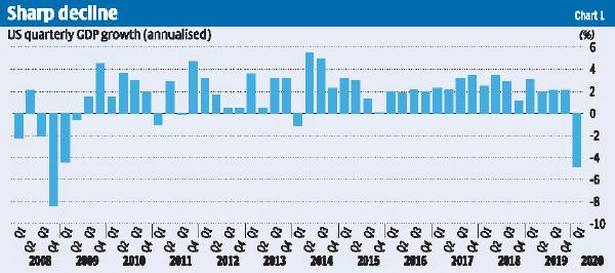

According to the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, GDP in the country contracted by 1.2 per cent in the first quarter of 2020 relative to the immediately preceding quarter, or at an annualised rate of 4.8 per cent (Chart 1). There is no comfort in the fact that despite being the sharpest contraction since the fourth quarter of 2008, this decline is less than the 8.4 per cent contraction experienced when the post-financial-crisis great recession in the U.S. was most intense. This is because the first quarter included only one month (March) when the combined effect of the pandemic and the regionally graded lockdown was felt in full.

There is no comfort in the fact that despite being the sharpest contraction since the fourth quarter of 2008, this decline is less than the 8.4 per cent contraction experienced when the post-financial-crisis great recession in the U.S. was most intense. This is because the first quarter included only one month (March) when the combined effect of the pandemic and the regionally graded lockdown was felt in full.

After the first quarter, that impact was felt in April as well and, despite talk of relaxation of the lockdown, is expected to be significant in May. Policy and social attitudes, influenced by the experience with the spread of the infection, would determine what happens in June and after. But even optimistic estimates point to a 20-30 per cent year-on-year output contraction in the U.S. in the second quarter of 2020.

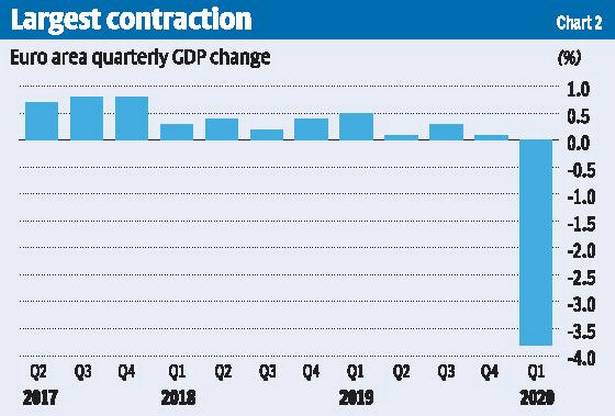

The data from the 19-member Eurozone are similar, with figures from Eurostat pointing to a GDP contraction of 3.8 per cent in the first quarter of 2020 (Chart 2)–the largest fall since Eurozone figures began to be published in 1995; and larger than the contraction in the first quarter of 2009, when the Great Recession overwhelmed the region. Though smaller than in the U.S., this contraction comes after a long period of slow growth, whereas the U.S. had seen its longest economic expansion on record. Moreover, here too, stringent lockdowns were introduced only in March, so the scenario is likely to only worsen over the next quarter, and possibly even later.

Moreover, here too, stringent lockdowns were introduced only in March, so the scenario is likely to only worsen over the next quarter, and possibly even later.

Drivers of GDP

The drivers of the downturn in terms of the relative contribution of different components of GDP to the contraction seem to tell a story. As has been widely noted, the output contraction induced by the COVID crisis and response is of two kinds. One is the sudden stop in production resulting from the containment policies.

These included constraints on activities that require the joint presence of people at the place of work or the point of consumption (such as in aircraft, restaurants, hospitals offering services other than treatment of COVID-related ailments, or venues hosting cultural or sporting events). This translates into an inability to use capacities that are in place or to resort to the consumption of certain services. And when existing capacities are unutilised, investment would not be forthcoming.

The other element influencing GDP movements is the collapse in demand, resulting from the loss of employment and incomes triggered by the first element, especially for commodities and services that are inessential or for which purchases can be easily postponed.

Unemployment in the U.S. has risen sharply to 18 per cent, as reflected in the 30 million new claims for unemployment benefits in the six weeks since the lockdowns first began. But not all who have been pushed out of work have been able to make their claims, and many are not eligible for these benefits, so some estimates suggest that the actual number of jobs lost could be as much as 1.5 times that figure. In the Eurozone, the unemployment rate had been creeping down from 7.7 per cent in March to 7.3 per cent in December, 2019, remained at that level for the next two months and rose slightly to 7.4 per cent in March 2020.

Consumption expenditure

Rising unemployment and falling incomes would impact consumption–moderated only by the interventionist schemes, if any–of governments seeking to make transfers to those who have partially or fully lost their sources of income. This does seem to come through in the figures on the movements in the different components of GDP.

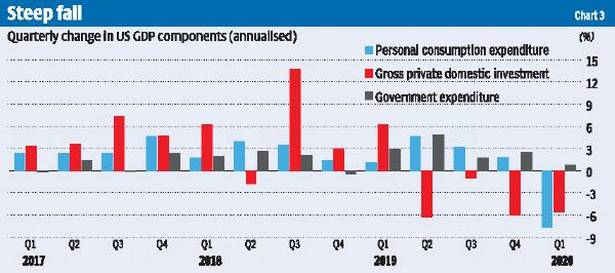

In the US, the sharpest fall in the first quarter of 2020 was in personal consumption expenditure, which contracted by 7.6 per cent (annualised) relative to the previous quarter (Chart 3). What is noteworthy is that the demand for goods contracted only by 0.3 per cent, with the fall in demand for durable goods (-1.21 per cent), especially motor vehicles and parts (-0.9 cent), being partly neutralised by the increase in demand for “food and beverages for off-premises consumption”, which rose by 1.1 per cent as households stocked up in the context of the lockdown. The focus of the demand compression is the services sector. Influenced by shrinking demand, private investment, which had already been contracting over the previous three quarters, fell by a further 5.6 per cent. What is noteworthy is that, as of the first quarter of 2020, the contribution of government expenditure to the GDP growth was woefully inadequate to combat the effects of the contraction in personal consumption and private investment. This was partly because the $2.2-trillion U.S. stimulus package, subsequently enhanced to around $3 trillion–including a one-time transfer to individuals and improved unemployment benefits–was announced only at the end of March.

Influenced by shrinking demand, private investment, which had already been contracting over the previous three quarters, fell by a further 5.6 per cent. What is noteworthy is that, as of the first quarter of 2020, the contribution of government expenditure to the GDP growth was woefully inadequate to combat the effects of the contraction in personal consumption and private investment. This was partly because the $2.2-trillion U.S. stimulus package, subsequently enhanced to around $3 trillion–including a one-time transfer to individuals and improved unemployment benefits–was announced only at the end of March.

How much of a difference the stimulus would make would be known only when figures for the next quarter are released in July.

In the Eurozone too, final household consumption expenditure of households fell in the first quarter of 2020 by 3.1 per cent in Austria, 7.3 per cent in Spain, and 6 per cent in France (the countries for which figures have been released). Here too, individual countries have announced and initiated implementation of stimulus packages.

But the sizes of these packages vary from 9 per cent of GDP in Austria, 5 per cent in France, and 4.9 per cent in Germany, to only 1.6 per cent in Spain and 1.4 per cent in Italy.

There is little agreement on a strong joint stimulus effort across the Eurozone. Rigid EU rules limit the ability of precisely those countries that need larger fiscal stimuli.

Credit push

However, there appears to be one element in the response packages to the COVID-induced crisis in the U.S. and the Euro area, which might explain the nature of the contraction in these countries. This is the overwhelming reliance on reaching credit to governments and businesses as a means of stimulating a recovery.

If the contraction is due to the collapse of consumption, in turn because of loss of jobs and incomes, the stimulus must focus on reviving demand, especially consumption demand.

But for that to occur, firms and enterprises would need more than just credit to keep them afloat and ready to respond to increases in demand. They would need support to resume production and re-employ the millions of people who have been displaced from their occupations. This would require a hugely enhanced fiscal stimulus in the form of income transfers to spur demand and support the resumption of production.

Given the uncertainty over the duration of the pandemic, the recession is bound to be prolonged and recovery delayed. But if the needed fiscal effort is not put in place, even a delayedeconomic recovery may proveto be elusive.