Our world is historical.

Take a virus, which might appear to stand outside history–genes surely do not care whether they flow through serfs and lords or infect Amazon delivery workers and investment portfolio managers–and you can quickly trace a story from its creation to its spread to its eventual cure that is saturated in history. Power and wealth weave the conditions in which we live and die, and power and wealth have not always taken the forms we know today.

After the financial crash of 2008, hundreds of millions of dollars flowed from New York to industrial meat production in China as bankers at Goldman Sachs hunted for safe investments. Partly as a result, large-scale industrial agriculture pushed smaller Chinese producers out into dangerous terrains where their animals came into contact with bats, which carry coronaviruses. None of this is immediately visible. Observers now decry instead the so-called ‘wet markets’ in Wuhan where the virus likely first reached humans; they focus on this visible sphere of commodity circulation–that moment when a shopper bought an infected pangolin–and so they reach nationalist answers to questions about how and why this all happened. It was China’s fault. This nationalism collapses once we uncover what Marx called the ‘hidden abode’: production. Restive capital in Manhattan, which must grow or die, produces new agricultural conditions thousands of miles away that then reshape how people grow and die.

Those who think COVID was produced in a secret laboratory are both nearly right and miserably wrong. They are right that the virus was produced. They are right that human beings create phenomena that then confront us as alien things not of our making–that is equally true of viruses and the machines that dominate our working days. The conspiracy theorists suspect, and they are right, that a great and damaging mystification has taken place to make us accept as natural and unavoidable forces that are created by a particular kind of society, which has not always existed and might not always exist in future. But they identify a single secret lab as the source of the crime because the real villain is so much bigger and harder to comprehend.

Once passed to people in China, the virus became a global pandemic so quickly because of the kind of world we inhabit. Within weeks, it had followed supply chains that carry commodities from China to Europe. Wealthy travelers brought it into poorer countries and then washed and quarantined, bringing death to the poorest people in packed housing with bad sanitation. Refugees forced to travel without precautions carried it on their backs. It has spread in crowded prisons and in vast warehouses.

In treating it, human need is not the principle that immediately governs the allocation of our resources: hotel rooms now sit empty around the world while the lockdown leaves victims of domestic violence in urgent need of a safe bed; doctors are exposed to the virus, and die, because governments fret about buying protective equipment; meanwhile billionaires buy large bunkers to be safe. If a vaccine is found soon, the companies that develop it will not be eager to dole it out to the needy, unless they can pay. Our experience of this lockdown is so thoroughly socially variegated that nobody should now claim (as Marx thought several ‘utopians’ of his day believed) that it is relatively easy to step outside the injustices of our society and exit capitalism as individuals rather than transcending it for all.

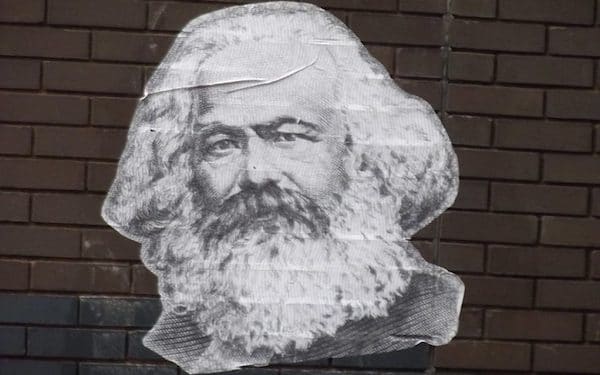

All of this brings renewed urgency to questions about why murderous irrationality proliferates. Who or what is to blame for privation in a world of plenty? This is not a bad time to convene a class on Marx, who grappled with a peculiar world and sought to explain why it looks and acts the way it does. He was not an economist seeking to predict tomorrow’s prices (though plenty have wanted him to be, including both critics and admirers). He sought instead to explain how that thing we call ‘the economy’ comes to dominate us.

Marx’s first intuitions were that social life is complex and that history mattered. His world, he thought, was being remade by an oblique process of dazzling potency and novelty. As a young social philosopher, Marx thought capitalism had transformed our experiences of social life and ourselves so radically that we could barely think outside its categories; and as a mature social theorist at the height of his powers, he attempted to chart the intricacies of that process. Two COVID anxieties–individual fears of potential unemployment and global worries about a future recession–offer useful entry points for rediscovering Marx.

Work

Why was it, in the first days of lockdown, that people spoke with enthusiasm of the new skills and new kinds of work they might undertake if freed from the obligation to travel to offices every day? Economists treat work as a disutility, across time and place a miserable thing undertaken in the hope of eventual rewards. Marx’s early interest in ‘alienation’ begins from a different premise worth pondering in this lockdown: that the activity of paid work removes something from the worker in historically particular ways that have to be explained.

Whereas slaves once produced for masters and peasants for lords under various whips, Marx saw a world of landless workers compelled to work not ultimately by any individual boss but by an abstract imperative. Divested of the means to reproduce themselves, to feed and clothe themselves, workers were dependent on a thing called ‘the market’ and so on work handed out by property owners. A peasant might rebel, burn down the lord’s manor and use her land to feed herself, but everyone anxious right now about losing their job knows that our position is quite different, that most of us need to work for others in order to survive.

The label ‘alienation’ does not name a psychological problem–work that feels disempowering to some workers. It describes a modern condition in which the form of our labour reflects our disempowerment, however we feel about it. We produce not directly to meet our needs but rather to coat in layer upon layer of gold the power of those bosses who direct our production. We cannot but do so.

Marx was no moralist because he was interested in the apparently tragic dimensions of a world where people good or bad were deprived of any means of survival beyond working hard erecting the conditions of their own domination. Even our bosses and the self-employed are compelled to make profits or go under. Profit rules like a heavy weight even over individual profiteers. Capitalists are only awful ‘bearers’ (as Marx had it) of a broader problem not reducible to individuals.

With dizzying irony, the fact of our servitude to this abstraction makes us see society misleadingly as a space of warring individuals and nothing else, since every wage-earner must face the world as an individual battling to secure her own pay. The structure of capitalist power works to obscure itself. And so conspiracy theories abound about evil Chinese doctors.

Time

Capital presents a new kind of interpretive challenge, since explaining the world it creates requires understanding the abstract principle of compulsive accumulation that governs our lives. Marx saw the need–as Louis Althusser put it–for a new object of analysis, the historically changing ‘mode of production’.

Take one current problem as an example: why does COVID-19 threaten to bring a long and deep recession even if a vaccine were discovered and administered tomorrow? In a different world, like one in which peasant producers lived on the land they worked, the end of the virus would bring with it the ability for those who survived to pick up tools again and get back to work (even as a depleted population might mean much less productive capacity). Capitalism is different. Market dependence, a society where we all must engage in market exchange in order to reproduce ourselves every day, requires constant activity. For every restaurant closed and every waiter who stops working, his lost pay packet amounts to one less consumer buying the holiday he had planned or the new sofa he wanted.

When millions are put in that position, the networks of credit that fund production are thrown into turmoil. Capitalists make investment decisions drawn by the promise of future value, so today’s loss of production without a guarantee about when it might resume means havoc long into the future. We are ruled now not by the time of royal reigns which defined the historical awareness of Medieval chroniclers, but by the ‘empty homogenous time’ of the factory clock dividing production into endless hours and minutes.

This new relationship to time, where tomorrow will surely die unless we are chained to our work today, is the achievement of a particular mode of production. Its precondition is concentrated ownership of the world’s resources, forcing most of us to survive by selling our labour to others. The result is ascendant valorisation, where market dependence converts ever-more spheres of life into market exchanges whose goal is to produce value that can be realised in exchange: sold. That turns endless accumulation into a compulsion, and so it produces the death drive that sees capitalists eager to burn the Amazon or push workers into unsafe factories without equipment to protect them from a rampant virus; death for the species might mean profit for the individual, and sometimes only active resistance can save our lives.

In the decades after his death, Marx was increasingly cast as a Ricardian partisan of the ‘labour theory of value’, celebrating labour as a great virtue under-rewarded by capitalists. But his interest in labour was analytical more than normative: that is, he wanted to know how the thing we now call ‘the economy’ as a realm separable from the rest of our social lives was constructed by a massive transformation that turned all work into a tradeable commodity and so harnessed us to the service of ever-expanding production.

Think now of the recent fretting about a choice between saving lives and saving ‘the economy’–think of the Texan politician who suggested old people might be willing to sacrifice themselves to get ‘the economy’ moving again. Marx wanted not simply to condemn such thinking as plenty of others have done, but rather to show how it had become possible. He wanted to show that even the most basic categories underpinning today’s thinking had emerged out of an earlier and quite different world.

Back to the future?

Marx’s way of thinking is stranger to us, and potentially more revelatory too, than is sometimes supposed. For instance, where states and ‘free’ markets are often talked about as opposites now, Marx inhabited a nineteenth century intellectual climate that preferred to identify the shared roots of apparently disparate things. He saw the capitalist mode of production as a social totality incorporating state as well as corporate power; that might now help us to think about furlough schemes to keep companies afloat and workers paid, with state intervention and even nationalisation as a crutch for capitalist production and not an alternative to it. Adding to his purported statism, Marx is usually treated in current popular debates as a chronicler of class struggle alone–simply siding with workers against bosses where really he attempted an account of why there are workers and bosses at all, and why that structure offered possibilities for its own supersession.

COVID-19 has altered our experiences of work and time and the state. Altered experiences can provoke questions about what these phenomena really are.

Against this backdrop, I will be teaching an introductory class of four sessions–open to all–on Marx, launching the London programme of the excellent Brooklyn Institute for Social Research. Interested neither in hagiography nor condemnation, we will seek instead to understand what precise intellectual problems preoccupied Marx and how he tackled them. His questions, and not only his arguments, might surprise contemporary readers. We will see the grandeur of his theoretical project. He sought a holistic account of capitalist social relations and the intellectual forms thrown up by them, misrecognising them–like the nationalism, conspiracy thinking and individualism I have mentioned here. His critical social theory promised to displace the old questions of economists and philosophers by showing how their questions were produced by the society Marx described, as its partial and distorted reflections.

And we will tackle the thorniest issue, which I have studiously avoided here: if the world that Marx described remains familiar to us in some ways, very much of it now seems strange and gone too. What is living, then, and what is dead in Marx’s sense of how capital might be transcended?