For decades, Cuba has sent tens of thousands of its medical professionals abroad to work in countries where natural disasters or poverty have left people without healthcare. In the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, and the catastrophic U.S. response to it, the absurdity of a propaganda war against Cuban medical missions has become more obvious than ever. But you can’t rely on corporate media to explain why.

An article cited by Sen. Marco Rubio in support of punishing Cuba was debunked at the time by FAIR (3/26/19).

On May 7, 2019, U.S. Sen. Marco Rubio wrote a letter that urged Secretary of State Mike Pompeo to increase pressure on governments benefiting from what he alleged was the “forced labor” of Cuban doctors. Rubio’s letter even claimed that the practice constitutes “human trafficking” by Cuba. Two months later, Pompeo took to Twitter announcing new sanctions on Cuban officials involved with its medical missions.

One piece of supposed evidence Rubio presented in the letter was a New York Times article (3/17/19) from last year by Nicholas Casey, which was completely dismantled by Lucas Koerner and Ricardo Vaz on FAIR.org (3/26/19). Casey’s article bizarrely depicted Cuban doctors in Venezuela as agents of the Cuban government who coerce voters and even perpetrate electoral fraud.

Last month, Michael Kozak, assistant U.S. secretary of State for the Western Hemisphere, reiterated Rubio’s attack lines on the Cuban missions. He scolded governments who accept Cuba’s medical help by saying,

Crises don’t justify trafficking medical professionals, who need protection now more than ever.

Spreading allegations that don’t stand up to minimal scrutiny is the opposite of caring about the working conditions of the doctors. But the sources U.S. journalists usually rely on—the right-wing media in Venezuela, for example—have been doing that for many years.

From inciting violence to demanding liberation

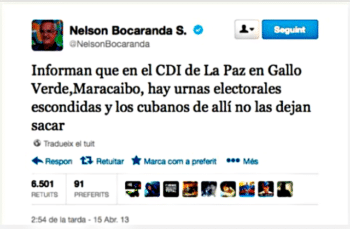

In 2013, as 18 medical centers in Venezuela were set ablaze by supporters of the U.S.-backed opposition, one prominent opposition journalist, Nelson Bocaranda, spread an allegation to about a million Twitter followers (4/15/13) that Cuban doctors were hiding away voting materials inside medical centers.

Journalist Eirik Vold moved to Venezuela in 2002, and initially lived in a wealthy part of Caracas, where everyone seemed to consume vehemently anti-government private media. He wrote in his book Hugo Chavez: The Bolivarian Revolution Up Close (p. 148; see also Venezuelanalysis, 4/7/17):

The first time I heard about the Cuban doctors, for example, was in an El Universal article that described the scandal of a child who died from alleged malpractice at the hands of a Cuban doctor.

But in the U.S., as the COVID-19 pandemic resulted in increased demand for Cuban doctors around the world, the emphasis appears to have shifted from vilifying them to casting them as victims of exploitation.

Belén Fernandez has already addressed for FAIR (4/14/20) some of the wilder claims about Cuba’s medical brigades that have appeared in the U.S. media. Examples include the frenzied output of the Wall Street Journal’s Mary Anastasia O’Grady (3/22/20), and her editors who denounced Cuba’s supposed “slave trade in doctors”; and the Panam Post (3/30/20), which claimed Cuba has a “shortage of hospital staff” because of its medical brigades. As Fernandez noted, the latter claim was so outlandish that even Reuters (3/22/20) debunked it, noting that even subtracting doctors serving abroad, Cuba still has “one of the highest” number of doctors per capita in the world. “It’s hard to avoid them” in Cuba, wrote British journalist Ed Augustin (Nation, 5/22/20), who has been based in Havana for the past seven years.

How does Cuba pay for it?

In fact, according to the UNICEF figures, Cuba has since 2000 consistently maintained a lower child mortality rate than the U.S. Since 2009, it has also maintained a lower infant mortality rate than Canada. That’s an astounding achievement for a country under a ruthless U.S. embargo for 60 years.

Independent U.S.-based journalist Reed Lindsay and his team at Belly of the Beast have begun to produce documentary videos on Cuba. One short video succinctly captures Cuba’s proactive approach to healthcare that, combined with an ample supply of doctors, helps explain Cuba’s success.

Sometimes U.S. corporate media produce articles that subject the claims made about Cuba’s medical brigades to some scrutiny, albeit very inadequately. One example is a Washington Post article (4/10/20) by Anthony Faiola and Kimberley Brown, which quoted Jose Miguel Vivanco of Human Rights Watch (HRW):

What these doctors are doing is heroic. But how the Cuban [government] treats them is disgraceful, taking credit for their good deeds while pocketing most of their earnings, denying them basic freedoms of speech and movement, and keeping them and their families back in Cuba in a situation of perpetual duress.

Vivanco’s (and HRW’s) pro-imperial bias is something I’ve written about before for FAIR (8/31/18). In a recent Spanish-language interview (BrujulaDigital, 5/15/20) Vivanco referred to the U.S.-backed dictatorship in Bolivia, installed in a military coup incited by a dishonest OAS electoral audit (FAIR.org, 3/5/20), as a “democracy.”

So it’s very unsurprising that Vivanco would accuse Cuba, a state the U.S. treats as an enemy, of simply “pocketing” the hard currency it receives for sending doctors abroad, rather than investing, as it must, in the system that trains its medical professionals. Nobody made this obvious point in the Post article by Faiola and Brown. The article describes the medical brigades as “a major source of income,” but neither the reporters nor anyone they quoted noted that hard currency is required to sustain them—and Cuba’s healthcare system in general. Getting hard currency is especially important for Cuba, because U.S. sanctions greatly increase the costs of importing medicines, medical supplies and technology.

That’s quite an omission, when you consider how reflexively the question “how are you going to pay for it?” is thrown at U.S. politicians like Bernie Sanders who advocate Medicare for All (FAIR.org, 2/29/20) and free college (both of which Cuba has). If that’s considered a crucial question in the most powerful country in the world, why not in Cuba, a small island subjected to a brutal U.S. embargo? (By the way, that embargo has been overwhelmingly denounced by the UN General Assembly in 28 consecutive resolutions.)

Could socialism be a motivating factor?

I contacted John Kirk of Dalhousie University in Nova Scotia, who has researched Cuba’s foreign policy and its medical brigades for many years. He provided a credible analysis of why so many Cuban doctors choose to serve abroad.

Kirk lived with Cuban medical professionals as they worked in El Salvador and Guatemala. Over a 12-year period, he interviewed 270 Cuban doctors, nurses and technicians who had spent at least two years working abroad. One of Kirk’s books about Cuba is Healthcare Without Borders: Understanding Cuban Medical Internationalism (published by University Press of Florida).

Speaking by telephone, Kirk provided some figures for Cubans who had worked in Brazil:

They went because they earned $1,000 per month, as opposed to $70 back in Havana. Yes, the Cuban government took 75 percent, $3,000 on top of the $1,000 that they earned. “How do you feel about that?” I asked [the doctors]. The general response was, “It would be nice to earn more money, but bear in mind that our regular salary, insignificant though it may be, is still being paid to our families back home. So what we are earning here is on top of the regular salaries. The money that goes into the Cuban government’s pot subsidizes the healthcare system for the entire population.”

In fact, even the one Cuban doctor the Washington Post (4/10/20) quoted (a defector, of course) said he volunteered to go on missions to make much more money than he could in Cuba.

Kirk said that nobody he interviewed claimed they were pressured to serve abroad; the monetary incentives alone make that very easy to believe. He added that many, for personal reasons, had turned down opportunities to go on second or third missions without repercussions.

Professional development is another incentive that Kirk mentioned—the opportunity to gain experience treating patients with conditions they would seldom (if ever) see in Cuba. He told me that when Ebola struck West Africa, the Cuban government had thousands more volunteers willing to go than it accepted.

Kirk described other incentives as well:

Another reason they went is because it is the kind of thing that everybody is doing—a kind of rite of passage. It’s like backpacking in Europe in the 1960s for North Americans: Everyone was doing it. At one point, 25 percent of Cuba’s doctors were working abroad. Everybody knew somebody who was abroad, or was about to go abroad. It’s also important to bear in mind the social ethos, if you like, the ethic of Cuban society. Kids from preschool are conditioned, socialized, whatever word you want to use, to think of themselves as part of a collective.

Another way to put it is that a socialist ideology can motivate people to help others. In Western media, socialist ideology is generally invoked only if it can be linked to repression or inefficiency, not a healthcare system in the Global South that in various ways outperforms those of many rich countries.

But Cuba is a dictatorship!

If anyone dares to point to any of Cuba’s achievements, the objection is inevitably raised that Cuba is a dictatorship. Cuba has indeed resorted to one-party rule to prevent itself from being destroyed by the U.S.—which, by the way, has killed tens of thousands of Venezuelans through economic sanctions since 2017, imposed in an effort to oust Venezuela’s democratically elected government.

In defiance of U.S. threats, Iranian tankers began to arrive in Venezuela on May 23, bringing desperately needed gasoline. Iran has formally complained to the UN about U.S. threats against the tankers.

Democracy does not protect a foreign government from U.S. military or economic attack—mainly because U.S.’s own democracy is severely stunted by its corporate media. They constrain every public debate, including those about Cuba’s medical brigades or anything related to Cuba.