To read the mainstream press, you’d think that the U.S. economy—especially the economy from the standpoint of workers—is on the mend.

The New York Times is a good example:

The American economy gained 1.8 million jobs last month, even as the coronavirus surged in many parts of the country and newly reintroduced restrictions caused some businesses to close for a second time.

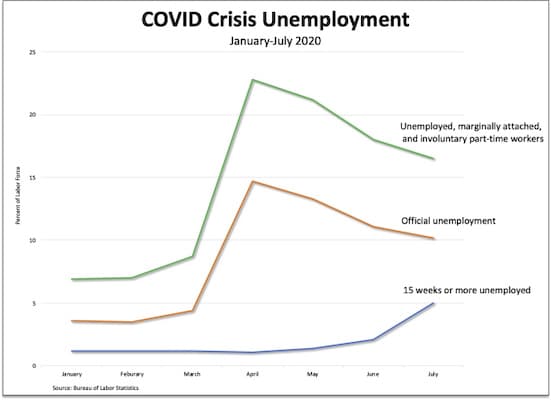

And, it’s true, both the official (U-3) unemployment rate (the orange line in the chart) and the more inclusive (U-6) rate (the green line) have fallen since April. But, at 10.2 and 16.5 percent, respectively, they’re still at or just below what they were during the worst period of the Second Great Depression.

Moreover the percentage of American workers who have been unemployed for 15 weeks or more is on the rise—and can be expected to continue to grow in the months ahead.

The massive Reserve Army of unemployed, long-term unemployed, discouraged, and underemployed workers is serving to discipline and punish workers, both those who have managed to keep their jobs and those who have lost them.

We know this because workers’ pay is going down. At the same time, workers are forced to have the freedom to commute to and labor at their jobs under perilous pandemic conditions, they’re being paid less. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, both the average hourly and weekly earnings for production and nonsupervisory workers fell between June and July of this year.*

Meanwhile, now that emergency federal benefits have expired, the unemployed—both continuing cases and newly laid-off workers—will not be receiving the $600-a-week supplement that helped them pay their bills through the spring and early summer.

Instead of raising workers’ wages, to mitigate the effects of the pandemic and to attract them back to work, employers and their political representatives prefer to slash unemployment benefits in order to compel workers to compete for the few jobs that are currently available.

Whichever way you look at it, American workers are the ones who are being forced to shoulder the lion’s share of the costs created by the COVID economic crisis.

*These numbers relate to production employees in mining and logging and manufacturing, construction employees, and nonsupervisory employees in the service-providing industries. These groups account for approximately four-fifths of the total employment on private nonfarm payrolls.