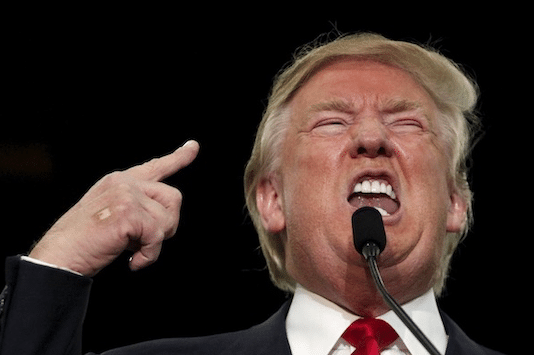

Since nationwide protests began this summer, President Trump has seemed a little paranoid. He has portrayed protesters, political opponents, and the press as domestic enemies working to destroy the nation from within. As if at war with his opponents, he even approved of the domestic use of military-style tactics, such as low-flying helicopters, riot gear, and tear gas. In July, as news broke of an unprecedented economic contraction, he floated the idea of delaying the November election. According to the president, treasonous actors among us have threatened the stability of the election. To the surprise of no one, Republicans have not put up much of a fight. They have mostly pretended they do not go on social media.

The truth is Trump’s paranoia is a political strategy, designed to drum up popular support and keep elites in line. Congressional leaders have long feared the president’s wrath because, more than any recent political figure, Trump has effectively harnessed what Richard Hofstadter called “the paranoid style” over a half-century ago.

The key to the paranoid style is its delusions of persecution. According to its rhetoricians, the nation’s enemies are lurking around every corner, threatening our security. They come from within government, too, what Trump often calls the “deep state.” Historically, paranoid rhetoricians such as Joseph McCarthy singled-out Catholics, communists, and intellectuals as anti-American figures of which we should be weary. Today, among President Trump’s scapegoats are members of Black Lives Matter, immigrants, liberals, President Obama, the media, and scientists who write about global warming.

In The Paranoid Style in American Politics (1963), Hofstadter described a style of communication that Americans would recognize today. One, Trump portrays the world in apocalyptic terms, constantly sounding the alarm about apparent subversives that are very nearly destroying the nation. The point is to present foes as being so dangerous that they must be stopped immediately, or at least held at bay. One analysis of Trump’s 2016 campaign found a clear pattern. He would first invoke feelings of national shame, frequently about China or Mexico. Then, he would direct anger at scapegoats. And, finally, he would promise a return to greatness under his leadership.

Two, the politically paranoid believes there can be no comprise in politics. Even a mild concession could cause the destruction of humanity. Just last week, in fact, a federal appeals court ruled against the administration’s incredible claim that it can willy-nilly terminate reporters’ credentials. But Trump knows he can never concede ground to his adversaries. As the White House presents it, Trump and his opponents are in a battle of good versus evil and our nation’s survival is at stake.

Three, since traditional news and educational systems cannot be trusted, alternative news sources are necessary. For Trump, CNN is “fake news” and The New York Times, though “failing,” remains dangerous.

Finally, Trump and others who speak the paranoid style are obsessed with proving their case. The result is an easily digestible account of the world, which, as Hofstadter wrote, is “far more coherent than the real world, since it leaves no room for mistakes, failures, or ambiguities.” Bad trade deals? The Clintons. Rioters in the streets? Anarchists. Things not so great? Make America great again! As Hofstadter put it, the paranoid rhetorician is “not a receiver” but a “transmitter.”

As a mode of communication, the paranoid style has no ideology. But we must not engage in false equivalencies: from Hofstadter’s time to today, most paranoid rhetoric belongs to the political right. This ideology, which Hofstadter identified as “pseudo-conservatism,” is not about preserving tradition, order, or values. Pseudo-conservatism is securing economic individualism and attacking the federal government. Such members of Congress see their job mostly in terms of casting “no” votes.

Hofstadter’s own politics were conservative by the standards of the 1950s and 1960s. Yet radicals today would do well to pay attention to his writings. Indeed, Hofstadter’s approach to history retained the radicalism of his youth. His books showed dialectical patterns (thesis—antithesis—synthesis) by discussing seemingly unimportant forces, almost a digression, whose later significance occasionally surprised readers. Furthermore, radical contemporaries such as C. Wright Mills also exposed paranoid far right rhetoric.

What ought to alarm us is not the presence of paranoid rhetoricians but the fact that they find an audience. Who would listen to such delusional claims? The answer may be helpful in an election year that has also become a year of protest.

The paranoid style preys on citizens’ resentment of their place in society. The strategy works by appealing to rather different groups. Monied interests resent being passed by in a changing economy. In the late nineteenth century, old patrician families saw their status overshadowed by the new industrialists. Today, we might come to similar conclusions about the old industrialists who are overshadowed by the tech leaders at Amazon, Google, and Facebook.

More important, however, are the feelings of resentment held by everyday citizens who see diminished prospects for the future. These include not only working-class families supported by coal and manufacturing, but also middle-class folks in office jobs and young people with few prospects for the future. President Trump’s misleading but seemingly straightforward commentary, which burdens our nation’s problems on scapegoats, remains appealing for those suffering economically.

We should begin by acknowledging that many people are justifiably worried about their ability to meet basic expenses. In appointing billionaires to his cabinet, passing a tax cut for the wealthy, and undermining the Affordable Care Act, President Trump does not act on behalf of everyday people. But, as an experienced prestidigitator, he nonetheless pretends to address the genuine concerns of those living in places like Pennsylvania, Wisconsin, and Michigan. It is not enough for Trump’s opponents to expose the illusion. They, too, must respond to the problems of late capitalism.

The paranoid style has become a mainstay of Republican politics. We should condemn its scapegoating. We should understand its appeal.