Lenin150 (Samizdat). Ed. by Hjalmar Jorge Joffre-Eichhorn and Patrick Anderson (translator), photography by Johann Salazar. Hamburg, Germany: KickAss Books, 2020, in English. 15 Euros for individuals and 50 for institutions. Books can be ordered directly from the editor at [email protected].

2020 is the birthday year of Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov, whom most of us know as Lenin. If still alive, he would be 150 years old. This explains part of the book’s title. There is also the word “samizdat,” commonly associated with the clandestine copying and distribution of literature banned by authoritarian regimes, especially in the formerly Communist countries of Eastern Europe. But here its meaning is simply: self-published. The book was deemed too weird for regular publishers to risk investing in.

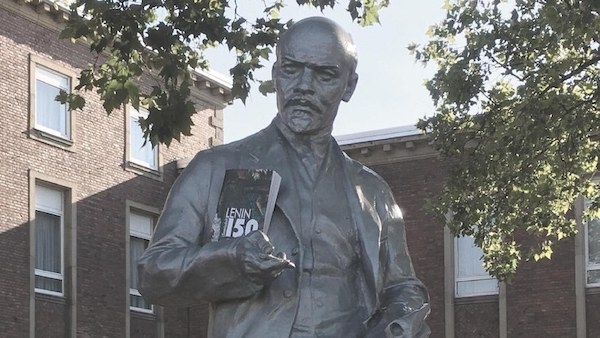

The unusual circumstances of its appearance make it a rare book from the very start, which will certainly give it a magnetic quality for collectors of literary esoterica. Aesthetically-speaking, it is also graced with an unusual (some might say beautiful) look–a detail of a colored glass mosaic of Lenin on the cover, and throughout a collection of photos by Johann Salazar of many Lenin statues and Communist monuments integrated into urban and rural landscapes.

This is a weird book indeed, blending Communist-nostalgia, sometimes whimsical/sometimes somber reflections on the realities of our time, cultural essays, poetry, revolutionary theory and dozens of photographs from a land far-away (except for those who happen to live there) called Kyrgyzstan, once part of the now-vanished USSR. The Kyrgyz Republic is a beautiful landlocked country in Central Asia frequented by the book’s editors and photographer during the early 21st century. The book focuses on a famous political “has-been” whom its twenty-six contributors believe is important–the leader of Russia’s 1917 Revolution in Communism’s earliest and heroic period, statues of whom still proliferate in this Central Asian republic.

Lenin150 (Samizdat) is a compelling volume for global handfuls (dozens, hundreds, thousands) of revolutionary-minded activists who are part of the radical ferment animating waves of dissent and protest sweeping the world. The international scope of this radical ferment, and of Lenin’s thought and influence, finds reflection in a very quick, rough count of the diverse homelands of the contributors: three from Kyrgyzstan, four from the United States, three from Germany, two from South Africa, two from China, two from France, and one each from Mexico, Argentina, India, Slovenia, Sweden, Switzerland and Britain–plus texts by the principal photographer (India/Portugal), translator/editor (Australia), and principal editor (Germany/Bolivia).

Glowing candles and dark times

Only one of these contributors knew the actually-living Lenin, and now that person is no less dead: Leon Trotsky. Reflecting on Lenin’s place in the history of Marxism, his comrade offered a bold comparison (which–Lenin’s widow Krupskaya affirmed–captivated Lenin during his final illness):

The entire Marx is contained in the Communist Manifesto, in the forward to his Critique [of Political Economy], in Capital. Even if he had not been the founder of the First International, he would always have remained what he is today. Lenin, on the other hand, is contained entirely in revolutionary action. His scientific works are only a preparation for action. If he never published a single book in the past, he would forever enter into history just as he enters it now: the leader of the proletarian revolution, the founder of the Third International.

Along with Trotsky, there are two more dead men in this volume: the famed playwright Bertolt Brecht (1898-1956) and Joomart Bokonbaev (1910-1944), a poet who is well-known only in his native Kyrgyzstan.

According to Bokonbaev, in his 1939 tribute at the time of Krupskaya’s death,

The hand of cunning death beckons us all, and

Only rests when we are laid in the black earth,

But those who struggled for the good of the people

Will never die, they will burn like candles.

Of course, a common judgment of the Communist order that Lenin and Krupskaya helped create–after so many good people perished under the crimson banner of the hammer and sickle–is often far more severe than this. Yet Brecht interceded, trying to explain to us the agonizing contradictions inherent in the life-and-death struggle between the laboring majorities and the wealthy elites, in the effort to replace the old order with a cooperative commonwealth:

You who will rise from the flood

In which we have floundered

Do not forget

When you speak of our weaknesses

The dark time

You have been spared.

Did we not endure, changing our country more often than our shoes

The wars of the classes, despairing

That there was only injustice and no outrage?Yet we know:

Even the hatred of baseness

Distorts the features.

Even anger at injustice

Hoarsens the voice. Oh we,

Who wished to lay the ground for kindness,

Could not ourselves be kind.

The inhumanity that many came to associate with Communism was inseparable from the dictatorship established by Lenin’s comrade Joseph Stalin, who took power after his mentor’s death. Mexican sociologist Elvira Concheiro Bórquez contrasts the qualities of their Marxism. She quotes Lenin’s insistence, in opposing rigid and dogmatic distortions of theory, that his comrades not “turn Marxism into something one-sided, distorted and lifeless.” She recounts how Stalin created a false idealization of Lenin’s–and now Stalin’s–party with the creation of “the cult of Lenin … accompanied by the dissemination of a narrow body of teaching, codifying Lenin’ work in accordance with the demands of the new authoritarian power imposed by Stalin.”

U.S. historian Ronald Suny goes further, connecting the propagation of lifeless theory with the brutal elimination of human lives. Brecht’s poem could cover violence in the time of Lenin and in the time of Stalin, but Suny sees a difference: “For Lenin, dictatorship and terror were necessary but undesirable means to a desired end; for Stalin they became both means and end.” While Lenin’s various policies “were adjustments to harsh realities,” he notes, “Stalin’s autocracy was declared by him to be socialism.” While Suny does not absolve Lenin from everything that Stalin did in his name, he insists:

Stalinism was both an outgrowth of aspects of Lenin’s Bolshevism and a malignant perversion of the original aspirations of the founders and the revolutionary masses who came into the streets in 1917.

Revolutionary politics

Alain Badiou pinpoints an essential element in the political aspirations represented by revolutionary socialists like Lenin. Traditionally, “politics is the range of processes that concern the control and management of the state apparatus.” For Lenin revolutionary politics involved “a division between populations with differing views as to its objective,” with the laboring majority seeking “the complete transformation … with a view to higher justice,” engaging in “a non-consensual discussion of politics itself.” The revolutionary masses come into the streets, moving to replace the old state apparatus with their own democratic councils.

But this does not happen by itself. It is the culmination of years in which activist minorities educate, agitate and organize, seeking to nurture mass insurgencies. Jodi Dean emphasizes Lenin’s engagement with the organizational practicalities that help make this so. Some in this volume are deeply critical of this aspect of Lenin’s politics (“Lenin clung to the concept of the vanguard party,” Kevin Anderson laments), but Dean is having none of that. “Solving the organizational problem, figuring out how to channel and direct political work, consumes Lenin,” she writes with evident approval. “He works out organizational questions incessantly, sleeplessly.”

Lenin’s linkage of democratic collectives as essential to revolutionary politics is also indicated in Wang Hui’s comments on Lenin’s “insistence on maintaining internal party democracy even under the most dangerous and difficult conditions.” He explains that this “was informed by Lenin’s theoretical-practical conviction that to abolish open and frank intra-party debate, criticism, and self-criticism, would extinguish the party’s life force by abandoning the principle of democratic centralism.”

Without such structures, how can the revolutionary-democratic politics that Badiou stresses become a reality? Revolutionary politics is not simply writing books and articles, speaking at conferences, going to meetings, participating in protests. Lenin and his comrades dared to reach, as Trotsky and Badiou tell us, for “proletarian revolution” involving “complete transformation.” Slavoj Žižek warns the Left against “the trap of oppositionalism” that prefers moralistic protests to fighting for power. South African activist Vashna Jagarnath comments that “the NGO-sector has often effectively shifted the insurgent popular political power built from below into the realm of workshops, petitions and technical sets of demands on the state,” adding that such activities have “no ability to rally the imagination of the working class and the most dispossessed in society behind a radically liberatory vision.” German theorist Michael Brie elaborates on the disastrous consequences of the various alternatives to the revolutionary socialist project:

Social democratic, green, and even communist parties have implemented neoliberal policies as partners in coalition governments of have failed to offer an effective alternative in opposition. Many citizens feel disappointed, betrayed even, by this failure of the Left–a failure to uphold its role as the protector of social well-being, democracy, the environment and peace. At best, it is simply waging defensive battles.

Lenin represents a politics that pushes beyond such limitations. It precludes coalition governments with either wing of the capitalist class and advances a strategic orientation that might well involve defensive battles but at the same time projects going beyond defensive battles–guided by what Georg Lukács identified in his succinct 1924 work Lenin: A Study in the Unity of His Thought as a sense of “the actuality of revolution.” This doesn’t mean that revolutions will necessarily be actualized. Inevitably, sometimes there will be defeats. But as Wang Hui puts it, “the true standard of defeat is not defeat in and of itself but whether the logic of struggle is able to persist and endure”–animated by a “philosophy of victory” seeking to advance “the will of the people.”

Learning from Lenin–and doing it differently

This subtitle, taken from Michael Brie, is a point made by more than one author in Lenin150 (Samizdat). Like many good lines, it can have more than one meaning. The first half, learning from Lenin, is suggested by all that has preceded this portion of the review. In fact, “doing it differently” is also consistent with learning from Lenin, since he more than once urged comrades of different countries to learn from the Russian revolutionaries’ experience but also to learn from their own very different social, economic, cultural and political contexts–which necessarily meant not attempting to replicate everything that the Bolsheviks had done, instead, to “do it differently.”

That has not been a simple thing. Owen Hatherley describes growing up in households where activist adults were convinced that “the Bolshevik October revolution was the most important and heroic event in human history. And that it could be repeated.” This included, he asserts, “a total fidelity to the party structures advocated in the Russian Social Democratic Labor Party for operating in a police state in the 1900s,” as well as “skewed ideas about their own history and uniqueness.” With such an approach, sects are created that will be incapable of accomplishing the sort of thing that Lenin and his comrades actually accomplished in their own time. (In a sense, such sectarians actually are“doing it differently”–while under the illusion that they are doing exactly what Lenin did.)

Vijay Prashad makes the same point: “Everything that Lenin wrote a hundred years ago is not to be taken as gospel. It is a guide. Circumstances change, developments must be studied carefully.” More than this, it can be argued that even in his own time, Lenin was hardly in a position to deal adequately with all matters of importance. We find Kevin Anderson noting that “Lenin neglected gender and the family in his writings and made no original theoretical contribution in this sphere.” Georgy Mamedov calls for the development of “A Leninist Perspective on Identity Politics,” observing that “the queer and feminist Marxist movements of the 1970s,” decades after Lenin’s death, found it necessary to transcend “the economism of the traditional Marxist understanding of the class struggle.” Such transcendence is suggested in What Is to Be Done? with Lenin’s “tribune of the people” argument, but Mamedov insists “the most important lesson a revolutionary Marxist can draw from Lenin’s theoretical and practical experience is that no theory of the past, however radical and uncompromising, contains a blueprint for action in the current circumstances.”

There is something more. Because Lenin was very much a human being, he sometimes, quite simply, got things wrong. We know this because that is what human beings sometimes do–get things wrong. (This aspect of Lenin’s humanity is explored in my 2017 study October Song: Bolshevik Triumph, Communist Tragedy 1917-1924.)

Lenin’s humanity surfaces in an interview conducted by the book’s editor with actress Ursina Lardi, who plays Lenin in a 2017 play on the dying revolutionary by Milo Rau. There are multiple facets of Lenin’s personality, conflicting qualities, that are part of her performance. One scene involves a conversation between Lenin and the People’s Commissar for Education, Anatoly Lunacharsky. Lenin asks: “How would you play Lenin?” Luncharsky responds: “To play Lenin as a human being would already be a mistake, I think.” Lenin’s companion Krupskaya reacts: “But why? Why would he not be a human being?” Yet in the course of the performance, Lenin is transformed into the revolutionary icon that he was made into: “Over the course of the evening I lose, one after the other, the things that make me who I am,” Lardi explains. But surely this is a form of degradation.

Asked what facets of Lenin’s thought and action we should “set free, revive of elaborate,” Lardi answers: “As long as one single human being is in bondage, oppression has not been eliminated! If the whole is not free, then our freedom is not worth a damn.”

South African activist Molaodi Wa Sekake–extolling Lenin as “a man of action and a defender of the integrity of revolutionary thought”–tells us:

We can only honor a man of Lenin’s stature by locating him in history; that is, by looking at how history shaped him and how he shaped it in return. To do so is to look at moments of progress and regress; of mishaps and happiness. To go about such a task requires our blatant refusal to bury or imprison the contours of history in hagiographies. We should, therefore, visit Lenin’s grave to work with him and against him (when the need arises).

Those who want to make fruitful use of this great revolutionary’s contributions will find much of value in Lenin150 (Samizdat). It doesn’t pretend to be the best introduction or the last word. But it is a fitting tribute and fine resource.