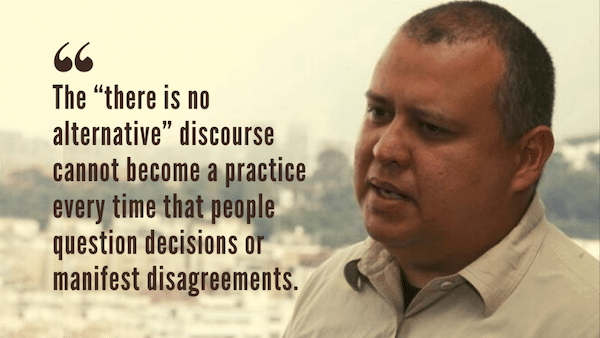

A blogger-come-minister, Reinaldo Iturriza has written creatively and insightfully about Chavismo and its contradictions. His work includes El chavismo salvaje (Wild Chavismo) and La política de los comunes (Politics of the Commons). In this VA interview, Iturriza addresses what is possibly the most difficult question facing Chavismo today: the political disaffection that can be found in important sectors of the Venezuelan people.

You have developed a creative reading of the Chavista identity over the years. Could you tell us something about this?

First, there is what is laid out in the El chavismo salvaje book, which basically gathers writings that go from 2007 to 2012. Among other things, it is a first attempt at identifying the tensions within Chavismo, an effort to present the logic of the different lines of force that traverse the movement, how they are expressed in practices, etc.

Writing these texts involved some abstraction in the attempt to capture the real movement–it was a dizzying exercise –, but at no point did I intend to position myself as an observer of Chavismo “from the outside.” On the contrary, these are militant writings. At that time I considered it imperative to explain what we had learned, what we had been, and where we were as a movement. It required working in two registers: on the one hand, recording what the experience of the Bolivarian Revolution meant to us; on the other hand, we had to construct a story outside of the propaganda, not make concessions to self-indulgent approaches.

The very concept of “wild Chavismo” is far from being a mere metaphor or attempt to provoke. What I pinpointed then is that there was an attempt to “brutalize” [brutalizar] Chavismo (in fact this is one of the founding practices of anti-Chavismo), but there was another attempt aimed at “stupefying it” [embrutecer]–this latter would become a characteristic of what I call “officialism” in my reflections.

Nonetheless, I highlighted that civil service, for example, was not by definition officialist, and that it is also possible to reproduce an officialist logic inside the grassroots movement. In synthesis, I tried to problematize the question of power, of its exercise, and also the question of the state and its institutions.

In the book [El chavismo salvaje], I raised issues of this kind and left open, as is inevitable, many questions. It was a starting point. From then on, I have tried to go deeper into some of these issues, while other themes have emerged.

In 2017, I wrote an essay (still unpublished): Chávez, lector de Nietzsche [Chávez, Reader of Nietzsche]. During the last years of his life, Chávez was a committed and unprejudiced reader of Nietzsche. And, as one would expect from a man like Chávez, his were not mere philosophical cavilings.

The Nietzsche readings, with others, inspired some major decisions. In fact, Chávez’s “Commune or Nothing,” the famous slogan, was born, at least in part, from Chávez’s peculiar and very heterodox reading of Nietzsche. Finally, in line with the analysis initiated in El chavismo salvaje and taking as a reference Gilles Deleuze’s interpretation of Nietzsche, I suggested that there was an “active” Chavismo that would set itself apart from “reactive” Chavismo.

In 2018 I wrote another book (also unpublished), La política de los comunes[Politics of the Commons], in which I collected some already published texts on the communal question in Venezuela. Among other things, I attempted to demonstrate that Chavismo breaks with the political culture of Acción Democrática [the social-democratic party that ruled for many years in Venezuela]. In other words, I argued that although there is a clear line of continuity between Accion Democratica’s political culture and that of Chavismo, what distinguishes the latter is precisely its singularity.

What does the singularity of Chavismo consist in? When is it born? A real “epistemological rupture”–as Chávez would call it–occurred in the 1990s when a young Bolivarian military contingent “discovered” the idée-force of participative and protagonist democracy. We were in the presence of a full-fledged theoretical and political event: by gravitating around this idea, revolutionary politics in Venezuela would never be the same. It marks a before and an after. I do not think I am exaggerating when I say that the Bolivarian Revolution becomes possible with this breakthrough. It changed everything and, in particular, the way of relating to the popular subject.

More recently, in 2019, I wrote a series of articles called Radiografía sentimental del chavismo [Sentimental X-ray of Chavismo], and I began to work on a line of research that I called Cuarentena [Quarantine]. The latter has nothing to do with the coronavirus pandemic, but with the fact that, in 2017, the most reactionary anti-Chavista lines of force became fervent promoters of the total economic blockade against Venezuela–a “quarantine” to contain and eradicate the “contagious disease” that is Chavismo.

Radiografía is an update of the analysis that I began in El chavismo salvaje. For example, what I identify in Radiografía as “disaffected Chavismo” is the most contemporary expression of wild Chavismo which, as far back as 2010, has been fed up with “dumb politics,” with the aggravating factor that [in recent times] this phenomenon of disaffection has become massive.

In Cuarentena I tried to identify the conditions triggering the phenomenon of political disaffection by delving into an area which I had not paid enough attention to until then: the economy. More than a pending issue at the personal level, I’m thinking that this–understanding the economy–is a pending collective task.

To give you an example, we have to understand the class composition of Venezuelan society today. But more than a snapshot of the current historical situation, I think we should understand the evolution of the class structure in Venezuelan society since the 1970s. Until we begin to gather such basic and crucial information, we will be condemned to repeat the same old generalizations about “oil rentierism,” “post-rentierism,” and other vague analyses.