The United States has declared the end of “business as usual” in U.S.-China relations. The escalation of recent months marks a bipartisan consensus: that the strategy of fostering political dependency through China’s economic integration into a U.S.-led world-system has failed.

As China’s rise exceeds the predetermined boundaries of the era of engagement, the U.S. turn to hybrid war makes clear that containment and engagement are flip sides of the same imperial agenda: the subjugation of Chinese sovereignty to U.S. interests.

In November of 1967, just months before announcing his entrance into the 1968 presidential race, Richard Nixon outlined in Foreign Affairs what would become a north star for Washington’s orientation towards China for the next half-century.

In an article titled “Asia after Viet Nam,” Nixon argued that the war in Vietnam had so occupied the minds of U.S. policymakers that it eclipsed the bigger picture. Vietnam—a small country on the rim of a vast continent—might have “filled the screen of our minds,” Nixon wrote, “but it does not fill the map.” The real white whale, the behemoth to be both feared and desired, was China.

“Red China,” Nixon argued, was too large a chunk of the world to remain isolated forever. The U.S. could not “afford to leave China forever outside the family of nations.” Preaching a path of “containment without isolation,” Nixon portended the defining U.S. strategy toward China for the next fifty years: wielding the carrot of integration into the “family of nations” and global trade alongside the stick of a militarized, industrialized U.S.-Pacific bloc. Such measures, in Nixon’s view, would be enough to “induce change…to persuade China that it must change.”

It is these final words—induce change—that Secretary of State Mike Pompeo lingered on while discussing recent turns in U.S.-China relations during a July speech at the Nixon Library in Orange County, California. Offering a critical assessment of the era of engagement Nixon began, Pompeo described Nixon’s premiere foreign policy achievement as a noble but ultimately naive exercise, setting the stage for decades of “blind engagement” that, rather than inducing change, propped up a “Frankenstein” China that perpetually deferred Washington’s hopes for an inevitable liberalization.

Pompeo’s was just one of several July speeches given by Trump administration officials who declared the end of “business as usual” and touted the administration’s “tough on China” record. Where prolonged trade negotiations begun in 2018 were premised on the notion that China could be cajoled once and for all into compliance with U.S. economic hegemony, this recent slate of speeches have sent a very different message. As Pompeo put it: “We can’t treat this incarnation of China as a normal country, just like any other.”

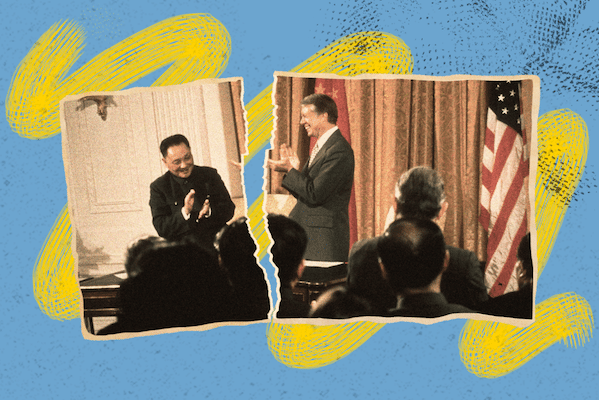

Indeed, in recent months and years the Trump administration has taken to treating China less like a troublesome rival and more like the “strategic competitor” identified in the Trump administration’s 2017 national security strategy document. The arrest of Huawei executive Meng Wanzhou in Canada in 2018; the designation of Chinese journalists as “foreign missions”; the pending bans on TikTok and WeChat; the scrutiny and surveillance of overseas Chinese students and scientists; the sanctioning of Chinese officials and companies operating in Hong Kong, Xinjiang, and the South China Sea; and finally, the forced closure of the Houston Chinese consulate—the city which famously hosted Deng Xiaoping during his historic 1979 visit to the United States—all represent a dense timeline of the U.S.-imposed escalation of U.S.-China relations under Donald Trump’s short tenure.

Where Nixon sought a strategic integration of China into the “family of nations”—a universalizing euphemism for the Western-led capitalist world order—the Trump administration is drawing new lines of containment to stop the supposed invasion of China’s Communist Party into U.S. cyberspace, supply chains, and spheres of influence. Indeed, while Nixon worried of an isolated China left to “nurture its fantasies [and] cherish its hates,” a recurring sentiment in the summer speeches offered by Pompeo, NSA Security Advisor Robert O’Brien, Attorney General William Barr, and FBI Director Chris Wray is that the deep integration of China into the world order represents the true threat, having produced not China’s liberalization but, as they argue, parasitism, subversion, and international acquiescence (“kowtowing,” in the parlance of China hawks).

In Barr’s words, the “many tentacles” of the Communist Party of China seek “to exploit the openness of our institutions in order to destroy them.” Here, China’s inevitable liberalization after integration into the world economy is turned on its head: as Pompeo put it: “If the free world doesn’t change China, communist China will surely change us.”

The crisis of Western liberalism, pressured on both sides by brewing separatist right-wing populist movements on the right and abolitionist movements against racial capitalism on the left, have undermined the triumphant “end of history” promised by the collapse of the Soviet Union. Compounded by the contradictions of a global pandemic which has been largely controlled by socialist states but led to prolonged, unabated outbreaks in much of the capitalist world, Western fears of a world order shaped by “Red China” reflect the untenable contradictions of liberalism and capitalism themselves.

The Terms of Engagement

Trumpian rhetoric on China’s rise poses decades of U.S. state and corporate overtures to China as a twenty-first century appeasement program, in which U.S. profit-seeking and naivete undermined the firm hand required to effectively force change in China’s political structure. NSA director Robert O’Brien described this new foreign policy truism as such: “The more we opened our markets to China, the thinking went, the more we invested capital in China, the more we trained PRC bureaucrats, scientists, engineers, and even military officers, the more China would become like us.”

But the apparent dichotomy between engagement and containment elides the fact that both share the same imperialist agenda. If the U.S. has turned (or more accurately, returned) to hybrid war on China, it is a change in tactics rather than one of desired outcomes. For Washington strategists, real bilateralism premised on China’s sovereignty and the legitimacy of its political and economic system has never been on the table.

Indeed, the shared “common sense” of both engagement and containment is a paternalistic, colonial attitude that the United States bears the right and the responsibility to “induce change” within China’s system. There is no debate over the ends, only the means: whether by co-option or by force, this is a dispute over the proper tools necessary to provoke China’s inevitable arrival at Western liberal-capitalist modernity.

A return to Washington’s debates over China policy in the late-twentieth century clarifies the ideological continuity between the past five presidential administrations, demonstrating the extent to which American chauvinism, imperial grandeur, and Western universalism has defined a consistent outlook, if a shifting toolkit, driving U.S. strategy towards China.

Post-Nixon diplomacy realized an earlier strain of thought with regards to China. In a series of speeches in 1957-1958, U.S. Secretary of State John Foster Dulles proposed “peaceful evolution” as a means to “shorten the expected life span of communism”—proposing ideas, lifestyle, and culture as the key fronts of an ideological war to subvert Chinese and Soviet communism. Yet the prospect of peaceful evolution worked in tandem with the reality of militarized containment. Stunned by their “loss of China,” the U.S. foreign policy establishment took a harsh posture by establishing an international trade embargo on the newly-established People’s Republic, waging hot war in Korea, and threatening nuclear brinkmanship during the First Taiwan Strait Crisis.

Those first decades after the establishment of the People’s Republic marked an era of uncertainty, in which Washington diplomats struggled to reach consensus on how to deal with a communist China after pouring billions of dollars in military aid and loans to the Nationalist Guomindang. To the contrary, Nixon’s detente—overdetermined by the geopolitical expediencies of the Cold War and the fallout of the Sino-Soviet split—heralded what Mike Pompeo describes as an “age of inevitability.”

As Margaret Thatcher and an ascendent neoliberal ideology declared “There Is No Alternative” to the Western capitalist model, the horsemen of capitalist convergence had reason to be optimistic. The Soviet policy of perestroika—political and economic liberalization—had begun the corrosive process that would lead to its collapse. It was in this era that Dulles’ notion of “peaceful evolution” resurfaced as a popular anxiety in Chinese political and intellectual circles. As Deng Xiaoping reflected in 1992, “The imperialists are pushing for peaceful evolution towards capitalism in China, placing their hopes on the generations that will come after us.”

Deng had long recognized that reform and opening up had introduced material and ideological aspects of capitalism into China. In Deng’s preferred metaphor, “opening the windows” to foreign capital brought fresh air as well as flies that must be fought. It was the firm hand of Party leadership which ensured the repression of capitalist elements and adherence to the socialist road. In particular, the Tiananmen protests of 1989 reflected the contradictions of reform and opening, making clear that the internalization of Western ideals of bourgeois liberalism on the part of the younger generations could spell the slow erosion of the socialist path.

It is in this context that Washington’s debates over relations with China in the 1990s adapted Nixon’s visions of China’s induction into the “family of nations” into a neoliberal vision of integrating China into the ladder of global capital and consumption—with the U.S. at its head.

Annual legislation to renew China’s most favored nation (MFN) trade status, which was made permanent in 2000, served as a recurring forum for debate over the efficacy of this influence-via-integration strategy. In a 1991 speech, George H.W. Bush invoked the “moral” reason for renewing MFN: “to export the ideals of freedom and democracy…to create a climate for democratic change.”

Bush’s optimism in the inevitability of regime collapse was no doubt informed by the looming dissolution of the Soviet Union after a half-decade of perestroika:

No nation on Earth has discovered a way to import the world’s goods and services while stopping foreign ideas at the border. Just as the democratic idea has transformed nations on every continent, so, too, change will inevitably come to China.

The tautology of tandem economic and political liberalization speaks both to the neoliberal fervor of the moment and to the long history of liberalism’s co-evolution with capitalism. Bush, like many others, linked “the cause of privatization and human rights” as one and the same. In classical liberal fashion, the right to private property and capital accumulation was posed as the fundamental right from which all other liberal political rights proceed. As Rep. Nancy Johnson (CT-R) put it while declaring her support for permanent MFN status in 2000: “When a Chinese realizes he has rights as an investor that government should not violate, the more likely he will also realize that he has other rights as a human being.”

President Bill Clinton’s case for China’s entry into the World Trade Organization was the same. Citing the interests of evangelical missionaries alongside those of big business, Clinton argued that by joining the WTO, China was agreeing not just to import U.S. products, but also to “import one of democracy’s most cherished values, economic freedom.”

A truck transports a shipping container at a port in Zhangjiagang, China, on Aug. 7. [Johannes Eisele/AFP/Getty Images]

These grandiose articulations of bourgeois “freedom” sugar-coated more pragmatic U.S. economic interests. A massive corporate lobby supporting MFN status for China framed the nation as an untapped market of “one billion customers.” In a 1997 speech on “China and the National Interest,” Clinton clearly linked “good jobs and higher incomes in our country” to the ability to make China a “magnet for our goods and services.”

Prioritizing U.S. interests meant stipulations on China’s integration: Clinton called for China to “dramatically improve access for foreign goods and services,” to “[tear] down trade barriers,” and to end favoritism and protectionism towards Chinese firms. That these same issues remain sticking points in the Trump administration’s trade war speaks to Washington’s consistent frustration that visions of free trade dependency remain stymied by China’s efforts to retain economic sovereignty within a capitalist world-system.

Far from appeasement, U.S. orientations towards China were guided by a confidence in China’s future as a dependency of Western capitalist power. Citing China’s dependence on foreign investment, Clinton in 1997 remarked that China was then the second largest recipient of foreign direct investment in the world—“linkages,” Clinton argued, that “bring with them powerful forces for change.”

Yet some on the left ignore the clear U.S. colonial aspirations behind the era of engagement to paint China as a willing junior partner to U.S. empire, imposing a retroactive narrative of U.S.-Chinese ideological alignment in the latter half of the Cold War. Certainly, U.S.-China rapprochement was borne out of the geopolitical expediencies of the Cold War, in particular China’s geopolitical and economic precarity following the Sino-Soviet split. But exaggerating the nature of an alignment of U.S.-China interests is to ignore the founding presuppositions of the U.S. engagement strategy: that Chinese engagement with the Western world order through trade, foreign direct investment, IMF loans, and ascension to international trade and diplomatic bodies would inevitably create the conditions for the erosion of Chinese sovereignty, socialism, and the leadership of the Communist Party itself. Far from ideological convergence, this era of engagement is more accurately described as the U.S. pursuit of regime change by other means.

Socialist development breaks the “Washington Consensus”

Much ink has been spilled describing China’s “economic miracle” in the decades following the lifting of the U.S. trade embargo in 1972 and the conditional restoration of normal trade relations in 1979. In 1980, China’s gross domestic product (GDP) per capita stood at $200. Today, that figure stands at over $10,000—meaning that the average Chinese person’s material circumstances have improved 50 times over in the past 40 years.

While cold warriors paint today’s China as a “Frankenstein” propped up by Western corporations and business interests depict China’s rise as ‘proof’ of the superiority of capitalism, Chinese development cannot be chalked up to a supposed embrace of the Western capitalist model. First, the strides of the Mao era in advancing health, lifespan, and literacy formed the bedrock of the labor force that drove China’s industrialization. Second, the nature of socialism with Chinese characteristics—namely restrictions on foreign control of critical industries, a decisive role of public industry, political control over capital rather than capitalist control of politics, and an emphasis on poverty alleviation—has rendered China one of the few developing nations to retain some semblance of political and economic independence amidst the introduction of Western capital.

China’s strides in poverty alleviation—with more than 80 million people being lifted from poverty since 2012 alone—speak to the unique, people-centered nature of its political economy. In a world-historic testament to the success of the Chinese socialist model, absolute poverty is slated to be eradicated in 2020. Such feats distinguish China from the majority of developing nations, where GDP growth does not necessarily correspond with a rise in standard of living for those at the bottom.

Understanding Chinese development as a product of market socialism rather than of capitalist triumph helps to explain the frustrations of Western policymakers who for decades have sought to force China towards political dependency and destabilization via economic liberalization. It is no surprise, then, that the very measures through which the Communist Party has sought to safeguard its economic sovereignty and avoided the pitfalls of free trade dependency are the same policies which have been doggedly targeted through international trade forums and unilateral U.S. trade aggression.

The consistency of Western demands on the terms of China’s economic engagement speak to the single mindedness of Western pursuits of financial domination over the fabled “El Dorado” of China’s market. As China negotiated for entrance to the World Trade Organization by committing to bring down tariffs, reduce state trading, and open its critical service sectors to foreign investment, Western media heralded the “ultimate privatization” of China at the hands of Western corporations.

Yet where Clinton in 1997 envisaged the extinction of “state-owned dinosaurs” which allegedly could not compete in the global marketplace, as of 2020, 82 out of China’s 119 Fortune 500 companies remain under state control. Barring the highly-anticipated collapse of China’s state-owned “zombie economy,” the imperialist powers have turned to the WTO as a trade polity bludgeon: between 2009 and 2015, 90% of WTO disputes amongst China, the U.S., Japan, and Germany have been taken up by the latter three against China. Most of these disputes hinge on attacking Chinese state involvement in the economy, from market caps on foreign ownership to state subsidies and state-owned enterprises.

To be sure, the influence of neoliberal ideals and a growth-oriented mindset which subsumed ideology under economics found significant footholds both in the Party and in Chinese civil society. But if the restructuring of some half of Chinese state-owned enterprises under Zhu Rongji between 1997 and 2003 marked the starkest lurch towards full privatization, China’s market was never fully “opened” to imperialist monopolist power in the way of most other “emergent” countries. Amidst China’s ascendance to the WTO in 2001, onlookers bemoaned that despite China’s growth as an export-oriented economy, it remained only “shallowly integrated” into the world economy, with state ownership over state-owned critical industries such as banking, communications, and energy remaining “insulated from international competition.” What Marxist economist Samir Amin called China’s “partial and controlled” globalization, particularly state control over its banking systems, is at the core of China’s fight for sovereignty within a capitalist world-system.

“Chimerica” as Imperial Parasitism

China’s entrance to the WTO, and its subsequent accumulation of U.S. debt reserves, heralded what Western pundits came to term “Chimerica”—an economic beast which now makes up 40% of world GDP. Regarded both with awe and fear, the Western capitalist class relished the role of China’s integration in suppressing the U.S. interest rate and subsidizing middle-class consumption with cheap imports. Yet economic nationalists were suspicious of the offshoring of manufacturing jobs and relinquishing of critical supply chains to Chinese control.

As the Trump administration attempts to sever the chimera under a new rhetoric of decoupling, these tendencies have found new relevance in recent re-appraisals of the two economies. On the one hand, narratives such as Newsweek’s 2019 cover story “How America’s Biggest Companies Made China Great Again” paint U.S.-China economic convergence as an American corporate bailout of an otherwise bloated and fading Chinese economy. On the other hand, U.S. reliance on Chinese supply chains has been painted as a dangerous economic and security threat—language emphasized amidst the COVID-19 pandemic, as China hawks such as Peter Navarro have insisted on a disastrous “American First” medical supply chain outside of ostensible Chinese control.

Yet neither framing captures the fundamental nature of the “Chimerica” relationship: one of imperialist parasitism. As mediated by the conferral of most favored nation trade status and WTO ascendance, the U.S.-China relationship is premised on an economic imbalance in which Western corporations reap the rewards of China’s massive, low-cost workforce while inflating Western consumption through access to cheap imports. Under these terms of engagement, China has historically borne the brunt of the West’s offshored resource extraction, dirty manufacturing, and waste exports. While decades of U.S. trade policy has decried a “trade imbalance” in China’s favor, the U.S. advantage is quantifiable: between 1978 and 2018, on average, one hour of American work was exchanged for almost forty hours of Chinese work.

The ubiquity of “Made in China” consumer goods in the 2000s—along with the racialized connotation that such products were necessarily cheap, dirty, or fabricated—spoke to a U.S.-China economic relationship that boiled down to the maxim “China produces, the U.S. consumes.” During the era of “open doors” and Opium Wars, British economist and critic of imperialism J.A. Hobson described the looming colonization of China as inevitably “draining the greatest potential reservoir of profit the world has ever known” in order to consume it in the West. The twenty-first century integration of China into the global capitalist economic system realized, in part, that age old imperial fantasy.

China’s willingness to enter into such terms is often misconstrued as a sign of a Chinese ruling party that is communist in name alone, indicative of a Chinese ‘state capitalism’ which has hitched its wagon to the West’s imperialist capitalist commerce. Yet, an understanding of socialism with Chinese characteristics situates Chinese engagement with Western capital instead as a fundamental bargain on the part of Party leadership. Since the 11th Central Committee plenaries between 1977 and 1982, the Party officially recognized the primary contradiction of Chinese society as “between the ever-growing material and cultural needs of the people and backward social production.” In Deng’s formulation, the fresh air of foreign investment, technology transfer, and productive advancement warranted the flies that inevitably came with it.

Controlled economic liberalization nonetheless created conditions for neoliberal thinking. An emphasis on economic growth arguably created a popular misunderstanding of the relationship between politics and economics, in what Wang Hui calls the “depoliticized politics” of the Deng era. Such thinking also coincided with pro-American ideology and a popular belief in the intertwined destinies of China and the United States. In the wake of the 2008 Western financial crisis, slogans such as “to save America is to save China” (救美国就是救中国) and “China-U.S. couple theory” (中美夫妻论) reflected China’s perceived national interest in stabilizing the capitalist world economy from internal collapse, and the belief that ideological and political divergences between China and the Western capitalist world could be resolved by economic cooperation alone.

Such faith in the intertwined fates of China and the United States evinces a critical underestimation of the preconditions of economic cooperation. While cloaked in the fervor of Cold War ideology, U.S. aggression on China is also decidedly material. After all, the alignment of China’s national development aspirations with the U.S. capitalist class’s thirst for a massive, cheap labor supply was always conditional on China “knowing its place” in the global supply ladder.

In this light, recurring Western demands for market access, privatization, and an end to state economic planning function as attempts to constrain China’s growth within the confines of a U.S. unipolar world. Chinese efforts to climb out of its predetermined role as the “world’s factory” are thus necessarily interpreted as an existential challenge to U.S. hegemony. Beneath the financial jargon of tariffs, currency manipulation, and most favored nation trade status, U.S. stipulations on China’s engagement in the world economy are fundamentally a question of imperialism, profit extraction, and economic sovereignty.

In fact, China’s ongoing economic restructuring over the last decade is very much in recognition of its over-dependence on Western capital—made all the more dire by the U.S. turn towards “decoupling.” In the wake of the 2008 financial crisis, a 2010 Chinese Ministry of Commerce report warned that for every $100 billion exports from China to the United States, the United States captures $80 billion in profits to China’s $20 billion. Similar reports quantified the “hegemony dividend” yielded by U.S. monopoly profits via dollar hegemony, debt seigniorage, and financial derivatives. This led China to refocus on domestic markets, “quality and innovation” over low-end exports, and industrial restructuring in its 12th Five Year Plan (2011-2015). This economic pivot consolidated under the Made In China 2025 initiative, which privileges innovation and domestic markets better described as Made by (and often, for) China.

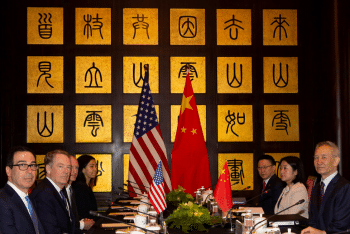

U.S. and Chinese officials, including Chinese Vice Premier Liu He, United States Trade Representative Robert Lighthizer, and Treasury Secretary Steve Mnuchin, meet during negotiations in Shanghai in July 2019. [Ng Han Guan/AFP/Getty Images]

In this light, the Western demonization of Xi Jinping as the personification of yet another “loss” of China has everything to do with the fact that under Xi’s tenure, China has consolidated the defense of the socialist tenets of its political economy—namely, an emphasis on Party leadership over the private sector, an expansion of the role of state-owned enterprises, and a clampdown on corrupt officials who exploited the influx of capital under reform and opening for personal gain. Coupled with the success of state economic planning in navigating the crisis of China’s COVID-19 pandemic and a forthcoming 5 Year Plan prioritizing “rural revitalization,” the turn towards the reinsertion of the state into economic planning and autonomy is likely to be further consolidated. Combined with a more assertive diplomatic and international stance through international initiatives such as the Belt and Road and the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, both of which reduce China’s dependence on Western markets and Western-controlled international institutions, the past decade has eroded any doubts as to whether China would join the ranks of Japan or South Korea as junior partners to a U.S.-led capitalist, imperialist world-system. To the chagrin of Western political elite, the era of “biding time, hiding strength” appears to have decisively passed.

Seen in this historical context, the so-called “trade war” between the U.S. and China is better understood as a last-ditch attempt to constrain China’s economic rise within the predetermined confines of the era of engagement. Former White House strategist Steve Bannon has proffered a surprisingly cogent assessment. Describing the urgency Beijing has placed behind Made In China 2025 in the context of U.S. sanctions on ZTE, Bannon stated: “They understand their weakness, how inextricably linked they are to the West.” In other words: hit the remaining spheres of Chinese dependence on Western capital—such as semiconductor chips and the SWIFT transfer system—before the full maturation of a Chinese innovation economy.

The hardline negotiation of phase one of a U.S.-China trade deal in January of 2020 portended to do just that. Decried by Chinese netizens and state media alike as a return to the neocolonial “unequal treaties” of the 19th century, phase one forced Chinese concessions on issues of intellectual property transfer, increased purchases of U.S. exports, and market access for U.S. financial services firms. The latter point, which sought to address what U.S. business interest groups decried as the “anemic” market share under strategic restrictions on foreign financial companies, led the U.S. financial sector to salivate over the prospect of “opening its $45 trillion financial industry.” Optimistic U.S. analysts promised that a phase two deal could target higher-hanging fruits: state subsidies, discrimination against foreign firms, and Made In China 2025 itself. But less than a year later, the signing of the phase one trade deal already feels as a relic from another era, a last attempt on the part of the U.S. to retain hegemony vis-a-vis China through bilateral negotiations rather than the unilateral aggression of recent months.

Case in point: just weeks after the inking of the deal, Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross remarked on the “bright side” of news of an unknown coronavirus strain cluster in Wuhan—the outbreak could “help to accelerate the return of jobs to North America.” Nine months later, the U.S. pandemic death toll sits at over 210,000, with 20.6 million jobs loss. What’s more, China has emerged as the only major economy to post GDP growth in Q2 of 2020—a modest 3.2% that nonetheless looms large over the U.S.’ 32.9% plunge.

The Trump administration has demurred on the possibility of phase two negotiations.

The Bipartisan Pivot to Asia

In retrospect, the trade war can be seen as a swan song for the era of engagement. COVID-19 has laid bare the vulnerabilities of the vast majority of Americans under neoliberalism, while China’s socialist pandemic response has set the foundations for an era-defining economic divergence. With the window of opportunity on curtailing China’s rise via bilateralism all but closed, the U.S. has pivoted instead to sanctions, decoupling, and militarization—the toolkit of a new containment doctrine.

Yet the “peaceful evolution” presupposed by U.S. engagement with China has always been overdetermined by the shadow of hot war and military encirclement. As Marxian scholars of world-systems theory have made clear, in the last instance, a structure of economic hegemony and dependency is always backed by military supremacy.

The “nuclear option” of lethal force has thus cast a long shadow on U.S.-China relations. From early Cold War proposals to bomb Chinese supply hubs during the Korean War or launch nuclear strikes during the first Taiwan Strait Crisis to the “accidental” bombing of the Chinese embassy in Belgrade by NATO in 1999, Chinese strategy has long been informed by recognition of what the U.S. euphemistically refers to as its “asymmetric military advantage” in Asia and the Pacific. Having watched two decades of largely unopposed U.S. military belligerence in the Middle East, China’s recent emphasis on military modernization is no doubt shaped by recognition of the U.S.’ favored means of dealing with geopolitical noncompliance.

U.S. attempts to renegotiate the terms of engagement over the last decade have similarly been backed by the quiet reshuffling of the U.S. military towards the “Pacific theater.” With less bombast but arguably more substance, the Obama administration’s military “Pivot to Asia” preceded the Trump administration’s labeling of China as a “strategic competitor” by shifting 60% of U.S. navy and air combat capacity to the Pacific theater. This military encirclement added heft to Obama’s free trade Trans-Pacific Partnership, which sought either to shore up U.S. regional economic power to the exclusion of China or integrate China into further conditions of economic liberalization.

The Trump administration’s prompt decision to withdraw the U.S. from the Trans-Pacific Partnership is often cited as proof of the turn in China policy between the two administrations. Yet, Trump’s military strategy has largely continued the shift initiated by Obama’s pivot to the Pacific theater. In 2019, Defense Secretary Mark Esper added rhetorical bluster to the Obama administration’s quiet calculations by declaring China the Pentagon’s “number one priority.” And in 2020, the U.S. Indo-Pacific Command released a budget plan titled “Regain the Advantage,” requesting $20 billion to retain military supremacy in the Asia-Pacific through a massive expansion of missile, radar, and “precision-strike networks” across Guam, Okinawa, and Hawai‘i.

The unity of U.S. military strategy towards China between the Obama and Trump administrations reflects a bipartisan consensus: “China’s rise” has exceeded the bounds acceptable to U.S. hegemony, creating diminishing returns for the parasitic U.S.-China relationship.

Meanwhile, it is clear the Democratic Party has no alternative to the program of unilateral escalation and deterioration of the U.S.-China relationship. Joe Biden has taken to ridiculing Trump for allowing China to perfect the “art of the steal” and condemned Trump for praising Xi Jinping’s early COVID-19 response, insisting that he would have demanded “boots on the ground” in Wuhan. In a preview of her likely policy agenda, Biden’s favored Defense Secretary Michèle Flournoy decried the “erosion of American deterrence” and called for new investment and innovation to “maintain the U.S. military’s edge” in Asia in the name of “peace.”

As in the old neoliberal formulation, “there is no alternative” to a Thucydides trap of the U.S.’ own making. To the detriment of humanity, the U.S. hegemonic worldview insists on distorting Chinese declarations of sovereignty, multilateralism, and “shared future for humankind” into threats of aggression and imperialization.

The end of engagement marks a critical reassessment on the part of the United States: that change in China cannot be “induced” through co-optive means alone. If hot war is considered off the table given the intertwined economies of the United States and China, then U.S. efforts towards economic decoupling must be understood also as military strategy, opening the door to a whole range of escalating tactics.

Yet, the end of engagement also poses a historic juncture between the paths of unilateralism and of multilateralism. Contrary to State Department fear mongering, China’s rise is not a threat to U.S. hegemony because China seeks its own hegemony. The real threat to U.S. hegemony is China’s role in ushering in a new era of multilateralism, in which institutions such as the UN once wielded as proxies of a hegemonic “Pax Americana” fulfill their promise instead as platforms for international peace and cooperation. China’s increasing commitments to UN peacekeeping forces, the World Health Organization, and international COVID-19 vaccine efforts such as COVAX all speak to China’s interest in bolstering rules-based multilateralism as a counterweight to ongoing U.S. belligerence.

Such are China’s rejoinders to the U.S. Cold War mentality. Before the United Nations General Assembly in September, President Xi Jinping declared that China “has no intention to fight either a Cold War or a hot one with any country,” rejecting zero sum geopolitics and calling for global cooperation to face the global crises of COVID-19 and climate change.

That Chinese sovereignty and the socialist path have been heralded as an existential threat to the Western alliance speaks far more to the nature of U.S. hegemony than it does to the character of China’s rise. After all, it is not China but the U.S. empire that insists on dividing the world into opposing camps. In the end, there are only two sides to be taken: the side of imperialism, unilateralism, and hegemony—and the side of the future.