Dear Friends,

Greetings from the desk of the Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research.

Any day now, Zambia will be the first African country to slip into a private debt default. It can only pay interest on the $3 billion in dollar-denominated bonds if it totally ignores the needs of the Zambian people. The country has suffered from the slowdown of the world economy, which impacted the sale of its copper for a part of this year (although copper prices and future prices have now begun to rise).

Cosmas Musumali, the general secretary of the Socialist Party of Zambia, says that the convulsions of indebtedness are not only due to the coronavirus recession but also to the wealthy bondholders and to the ‘cluelessness’ of the government of President Edgar Lungu of the Patriotic Front.

Zambia is one instance of what will be a cascade of defaults. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) estimated in April 2020 that at least 39 million people in sub-Saharan Africa will be forced into extreme poverty. Ken Ofori-Atta, the finance minister of Ghana, said in early October that ‘The ability of central banks in the west to respond [to the pandemic] to an unimaginable extent and the limits of our ability to respond are quite jarring’.

Ofori-Atta’s comment should be taken very seriously. In its October 2020 Fiscal Monitor Report, the IMF said that governments around the world have thus far spent or cut taxes to the tune of $11.7 trillion or 12% of global GDP. Through low interest rates, financial institutions are encouraging governments in Europe and in North America to borrow money to exit the coronavirus recession. The IMF’s managing director Kristalina Georgieva regularly says that countries must ‘spend. Keep the receipts. But spend’, and that this expenditure should go towards infrastructure. The World Bank’s chief economist Carmen Reinhart has said that even developing countries must take on new debt: ‘While the disease is raging, what else are you going to do? First you worry about fighting the war, then you figure out how to pay for it.’ To people like Ofori-Atta and Musumali, this is strange advice.

Ofori-Atta’s comment should be taken very seriously. In its October 2020 Fiscal Monitor Report, the IMF said that governments around the world have thus far spent or cut taxes to the tune of $11.7 trillion or 12% of global GDP. Through low interest rates, financial institutions are encouraging governments in Europe and in North America to borrow money to exit the coronavirus recession. The IMF’s managing director Kristalina Georgieva regularly says that countries must ‘spend. Keep the receipts. But spend’, and that this expenditure should go towards infrastructure. The World Bank’s chief economist Carmen Reinhart has said that even developing countries must take on new debt: ‘While the disease is raging, what else are you going to do? First you worry about fighting the war, then you figure out how to pay for it.’ To people like Ofori-Atta and Musumali, this is strange advice.

In November 2019, before the pandemic, Stephanie Blankenburg gave a presentation at the Debt Management Conference of the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD). As the head of the Debt and Development Finance Branch of UNCTAD, Blankenburg keeps a keen eye on the escalation of debt and its social impact. ‘Developing country external debt’, she said, ‘surpasses combined export earnings since 2016’. The World Bank’s International Debt Statistics 2021 shows that at the end of 2019, the total external debt of the developing countries was over $8 trillion. Ten months into the coronavirus recession has led close observers to estimate that the burden has increased to at least $11 trillion. Since 2016, developing countries were not able to finance their debt through export earnings. Now, none of the poorest countries will be able to service this debt; few will be able to ever clear it.

During the week of the annual IMF meeting, I asked Blankenburg whether the richer states–the G20, for instance–were serious about debt relief of any kind. ‘It depends what you mean by “serious”, but I assume you mean debt write-offs that return highly-indebted countries to a sustainable growth and development path’, she answered. If that is so, then, she said, ‘no, or not in any orderly and balanced fashion. Eventually, debt write-offs in the most vulnerable developing countries will be inevitable, and everybody recognises this, but the question is on what terms this will happen’.

As countries slip into default, their finance ministers find that they have almost no power to bargain their way out of a crisis; the terms are dictated to them. ‘Short-term creditor interests’, Blankenburg said, ‘are likely to keep the upper hand’. This means that financial institutions–driven by the compulsions of wealthy bond holders–will set the terms for the repayments of the odious debts. These terms are by now familiar; the financial institutions–and the governments of the richer countries that back them–will demand ‘conditionalities that favour austerity’, which, she said, will ‘undermine future growth prospects and carry high social costs for the population in the affected countries’.

‘In a nutshell’, Blankenburg told me, ‘the question is not so much whether there will be debt relief–there will have to be–but how this will come about’.

In 2015, the UN General Assembly adopted a resolution on the ‘Basic Principles on Sovereign Debt Restructuring Processes’. This resolution noted that any debt restructuring must follow the customary principles of sovereignty, good faith, transparency, legitimacy, equitable treatment, and sustainability. Behind this resolution lay another aim, namely, to overhaul the debt process and to create a mechanism for a comprehensive agreement over debt. This mechanism, it was hoped, would have the power to develop a comprehensive agreement on the galloping debt burden.

Attempts by the richer nations to handle debt–such as through the G20/Paris Club’s Debt Service Suspension Initiative (DSSI)–have not borne fruit. As Blankenburg explains, the DSSI ‘was monumentally complicated and only brought limited relief on commercial debt’ for the most indebted states; anything for the rest of the indebted poorer countries ‘would have to be bigger, faster, and smoother’. Mechanisms proposed by UNCTAD, she told me, are ‘not on the horizon so far’.

The problem is that the terms for the conversation are entirely set by the richer countries, led by the G20. They are of the view that only the creditors–and at most the IMF–should be in charge. ‘The danger here’, Blankenburg tells me, ‘is that short-term creditor-led considerations of the repayability of external debt prevails as the main criterion, and long-term sustainability and development concerns are disregarded’. In other words, the rich want their money, while the poor are left without any means to survive led alone thrive.

The IMF’s Georgieva is trying to rebrand the Fund as somehow no longer committed to structural adjustment and austerity. But her advertising campaign falls short compared to the policies of the IMF. An Oxfam study found that 84% of the loans offered to 67 countries during the coronavirus recession came with fiscal consolidation–or austerity–measures. These loans came through the IMF’s Rapid Credit Facility (RCF) and the Rapid Financing Instrument (RFI), both set up in April 2020, as well as the Catastrophe Containment and Relief Fund (CCRF).

On 16 October, Zambia’s finance minister Bwalya Ng’andu told parliament that his government is working with the G20/Paris Club’s DSSI for a six-month suspension in debt servicing payments. ‘Although we have obtained some relief under the DSSI window, particularly from official creditors’, Ng’andu said, ‘engagements with commercial creditors have not yet yielded the expected results’. And they likely will not, because–as Blankenburg told me–they are focused on short-term interests and have little care for the long-term well-being of countries such as Zambia.

Cosmas Musumali of the Socialist Party of Zambia told me that the situation is bleak for his country, since the proportion of concessional lending has relatively declined, sovereign debt has increased for most developing countries, and ‘the global campaign for debt forgiveness and cancellation is much weaker today’. Strengthening that campaign is vital.

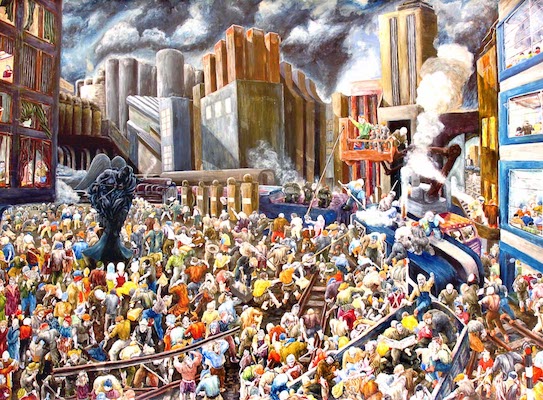

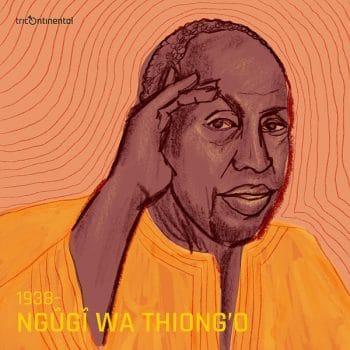

Not long ago, our friend Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, who is the author of the remarkable Petals of Blood (1977), wrote a poem called ‘Paradise for human victims of corporate persons’ (16 July 2020). It is written in the voice of the corporate leader talking to the workers of the world:

Know ye all that Corporations

For whom you work are persons

Their pursuit of profit is

Their persons’ pursuit of happiness.Concern for actual human health and happiness

Must give way to the person’s pursuit of profit

Well, not just profit, you fools,

But rising rate of profit.So:

Our Dear Workers march maskless and fearless into meat factories

Bring us profit

What does it matter if the factories are infected with coronavirus?To sacrifice your life for Corporate profit

Is the height of capitalist patriotism.

Know that if you die for our profit

We shall send your souls straight to Paradise.

From where you can enjoy us enjoying the palaces

For which you sacrificed your sweat, health, and blood.

The people of Bolivia rejected corporate leaders who want to sacrifice them for their sweat, health, and blood. By ballot box, the people swept away the coup government and reinstalled the Movement to Socialism. ‘We have regained democracy and hope’, said the next president of Bolivia, Luis Arce.

Warmly,

Vijay.