Peter Linebaugh interviewed by Johnny Flynn of Independent Left

Johnny Flynn: The first question I had to ask you was about the subtitle to your Red Round Globe Hot Burning: a tale at the crossroads of commons and closure, of love and terror, of race and class, and of Kate and Ned Despard. I saw you did a video that is up on the P. M. Press blog where you were talking about crossroads and you referenced Robert Johnson and the idea of being at the crossroads. The time of Edward Despard and Catherine Despard was one of commons and closure and race and class: the beginnings of this horrible white supremacy that we’re beset with now (with all these kinds of fascist berserkers that are all over the world gaining strength). The Despard’s attempt to overthrow the industrial capitalist system and restore the commons failed, and we ourselves are at the crossroads now between our plague-ridden current times and what they call the Anthropocene or the warming climate. Could you talk about that a little bit? How the two are related, if that even makes sense as a question?

Peter Linebaugh: It does make sense. The Anthropocene is basically putting carbon dioxide into the stratosphere, so taking what was underneath the earth and putting it on top of the earth has really messed the earth up, to be simple about it. But Despard, of course, was executed or hanged and decapitated in 1803 and this is at a time when–based on ice samples from the Antarctica–some geologists date the beginning of the pollution of the stratosphere with CO2. Carbon dioxide that’s still up there of course, that has led to global warming, planetary warming, species destruction, desertification and so on. So this is a planetary crisis now that we face.

The USA–or Turtle Island as I’ve taken to calling this part of the planet (based on the first names of the first peoples here, they say Turtle Island)–the USA is basically a product of Despard’s time, that is the 1790s. That’s the same as the UK, the United Kingdom. This was also the time of the Anthropocene. You take these two Uniteds–United Kingdom, United States of America–and try to understand how they are related to the factory and then how is the factory related to the plantation.

Taking the republic, the Anthropocene, white supremacy, the modes of production and put them together and it’s a massive attack, it’s a massive counterrevolution, I would even say, on the planet and on social life of not only two-footed critters but horses, livestock, other species. This is really mind blowing in the sense that it contradicts so many standard narratives, you know, of the scientific revolution, of industrial progress, of secular life, of the enlightenment.

I said four things. Let’s see: Anthropocene; the republics; white supremacy; modes of production. I’m sure I’m missing a few other fundamental pillars that had their foundations knit together in the 1790s. Thank you for remembering Robert Johnson and the crossroads because it was that blues tune–or rather the blues man–that was definitely in my mind. This Robert Johnson, the blues man from the Mississippi Delta, who was said to have made a pact with the devil at the crossroads where he was granted genius at the guitar and in music at the price of his soul. And far be it from me to do a sociology of the blues but it is one of the cultural expressions from Turtle Island that arose out of the plantation and against white supremacy.

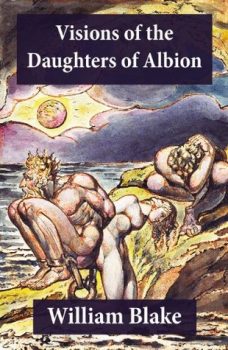

The dominant religion of white supremacy was this dualistic view of the devil versus Yahweh or a king of the universe, and Robert Johnson defied it in his music. And I see a direct relationship between that and William Blake. William Blake’s Visions of the Daughters of Albion is a beautiful meditation against white supremacy, against political domination, against the love of the body, against Eros, against the alienation of labour. It’s a great poem inspired by the Haitian revolt of 1791.

I’m trying to write a tale of the crossroads and I see that in Edward Despard, the last of many children of an Anglo Irish in County Queens or County Laois, and in Catherine Despard, who was really totally forgotten in history and was a descendant of Africans. They met in the Caribbean or somewhere in North America, maybe Central America, and they formed a revolutionary team, a partnership in the age of revolution, in the age of the United Irishmen and the age of the Haitian revolt, against which I think the United Kingdom and the USA were both formed. I see Ireland and Haiti, or the Caribbean islands, the Caribbean plantation, as kind of the one side of the barbells and the other side of the barbells is the UK and the USA, but again, this is perhaps an undialectical image.

The USA and the UK are past their sell-by date

Johnny Flynn: I remember your extraordinarily provocative statement in one of your talks where you were talking about the United Kingdom and United States. You said that they were both formed as a kind of destruction of the commons, especially in the case of the United States and the United Kingdom: let’s say against the 1798 revolution or attempted revolution of the United Irishmen. So the restoration of the commons would be predicated upon the destruction of what we know of as the United Kingdom and the United States. If I remember correctly, in one of your talks you said something like that?

Peter Linebaugh: I think the USA and the UK are definitely hanging on, gasping for life towards the end of their sell-by date. They’re no longer political organizations that can solve the problems that are facing us, beginning with the effects of the Anthropocene or planetary warming. Their answer, at least, has been to intensify class inequalities and to intensify white supremacy and they’re totally at a loss about what to do against very vibrant forces from the assemblies of the Occupy era from 2011, to the attempts at, quote, ‘socialist constitutions’ in Latin America, against the George Floyd uprising of this last summer. They’re not able to meet these challenges. Hey Johnny, by the way, thank you for saying the whole title, Red Round Globe Hot Burning.

Book cover based on original frontispiece of William Blake’s ‘Visions of the Daughters of Albion’, which inspired Peter Linebaugh’s book title for ‘Red Round Globe Hot Burning’.

Johnny Flynn: It’s a great title, sure it comes from Blake, the Visions of the Daughters of Albion.

Peter Linebaugh: It does.

Johnny Flynn: There is a great selection of literature in that book. Ciarán O’Rourke and I were thinking you could read through your book and just have people read from different texts that are assembled in the book, because it is like a kind of omnia sunt communia of radical culture and art. It’s like this extraordinary coming together of traditions and texts and everything. It’s just a fabulous work of art, historical art. Not many history books are works of art.

Peter Linebaugh: Thank you for sending me two of Ciarán O’Rourke’s poems.

Johnny Flynn: He’s a great poet. He’s a political poet as well, so he’s totally in love with the poetic tradition like Blake and John Clare and he’s a great source for me. It’s good to have a friend who’s a poet, you know?

Peter Linebaugh: Yeah, Edward Thompson kind of had a view of poetry as oracular, you know. As related to the prophets who were able to denounce the powers that be and the world as it is.

Peter Linebaugh on Thomas Spence

‘The Commons’ and ‘John Clare Enclosed’ two Poems by Ciarán O’Rourke inspired by the writings of Peter Linebaugh. First published in ‘Irish Pages’.

Johnny Flynn: Thomas Spence is like that. It’s incredible stuff. As you’re reading it, you feel like starting to shout or whatever because it’s so powerful, the stuff he’s saying and the way he says it. The rights of infants or when he’s talking about, ‘Yes, Molochs!’ And all this amazing stuff.

Peter Linebaugh: Yeah, I think Thomas Spence is in a different league. He’s in the streets rather than the drawing rooms, and I’m not saying Blake was not in the streets. He was. He would read aloud in the garden with his wife and they wouldn’t have their clothes on, which in good weather sounds… You’d want to have short poems! And he was also seen wandering around the streets of Lambeth with a bonnet rouge. But Spence definitely, he’s not only on the streets, he’s lying on the streets to do his chalking on the pavement.

Johnny Flynn: Just compelled to resist and in these imaginative ways, through songs and graffiti and his incredible pamphlets.

Peter Linebaugh: And his songs were to the tunes of popular tunes that remind me of the Wobblies, of the IWW, who would … or of Joe Hill who would take Salvation Army tunes and turn them into working class fighting songs.

Johnny Flynn: Who’s the guy who had, They go wild, simply wild over me? Not Joe Hill but the other great songwriter for the Wobblies. T-Bone Slim? Didn’t he have that one where he’s like, ‘They go wild, simply wild over me’? Where he’s saying the cops keep beating me up, the judge keeps putting me away all because I’m a class warrior.

Peter Linebaugh: T-Bone Slim spoke of civil insanity. I won’t say Spence started that tradition, because I think that goes back to Aesop and it goes back to Commedia dell’arte in Italy, or popular forms of song and popular forms of street actions, but definitely Joe Hill and T-Bone Slim are part of that, and it comes out of Spence. I love it.

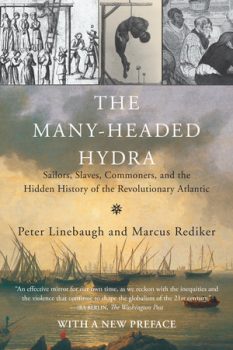

Johnny Flynn: Spence, he kind of radicalized Robert Wedderburn, didn’t he? You and Marcus Rediker have a great passage in your Many-Headed Hydra that describes Robert Wedderburn as a linchpin of the revolutionary Atlantic. It’s a great metaphor it’s brilliant. He’s a fascinating character, Robert Wedderburn. He’s a kind of Jubilee enthusiast like Spence as well: a big believer in the Jubilee.

Peter Linebaugh: That’s right, he was.

Johnny Flynn: Get rid of debts, free the slaves, all this kind of great, great vision, you know?

Peter Linebaugh: And leave the earth fallow for a year. That’s also in Jubilee, and that definitely pertains to our point in the crossroads. I was reading Nature Magazine yesterday; it has released this report that 30% of farmland needs to be turned into wild in order to preserve the planet. That notion of fallow, I think, is essential, and it’s in Jubilee as you were saying, along with debt forgiveness.

Capitalist separation and destruction of the commons

Johnny Flynn: You said that the commons is more forgiving or it’s more friendly to women and children and when it comes, the theft of the commons and the rise of industrial capitalism, women and children were prime victims, whether it’s in slave labour like the reproduction of slaves or actually in the factory system where children were literally being fed into machines at the behest of these capitalist. Whereas the commons was a place of love and solidarity but it was also a formidable place with all these different Commoning traditions. And as with your book, Red Round GlobeHot Burning, it’s not explicitly called an international but it is kind of an international of these different Commoning traditions as Despard and Catherine’s journey is navigated through all these different traditions: from Ireland, to the Miskito Indians to the Mayans and the Iroquois, all these different, great Commoning traditions.

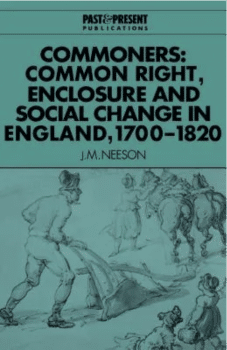

Peter Linebaugh: It is, but they never do quite get together. That was the point of his execution: to demonstrate to the world what happens if you try to get them together. But I want to get back to your other point about how the commons is friendlier to women and to children, because that’s a thought that I learned from my colleague, our colleague, Janet Neeson, who wrote the wonderful book called Commoners, which I think is probably the finest book on the commons in England during this period, during the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. She’s the one who taught me that the work of gleaning, the work of pasturage, is something for children as well as for men and women. In fact, just as I was talking, I was thinking of James Joyce. I think as a kid he used to go up into the hills–what do they call it? Booleying?–to look after pasturage of, I suppose, sheep. I’d like to read more about it, but I know he did that. But getting back to the commons and the family life, the family is not just around the kitchen or not just around the hearth, it’s also outside. It’s in the field or in the woods, and here, the family will go. I’m not sure the ramifications of that have been sufficiently explored by historians. I may want to attempt it here with the chapter on the goose, to describe children’s, quote, ‘literature.’

Long before it was literature, it was oral songs and rhymes, not for the nursery but for children, and it took place outside where lessons of cooperation and of sharing would be taught in practice by parents to children. So, then as you say, the factory will put an end and will start to create the divisions between the, quote, ‘public sphere and private sphere’ or the women’s realm and the public reserve for men. We’re still, of course, suffering the ramifications of that, as men can no longer rely on domination as their form of leadership and women are no longer consigned just to compliance and obedience. These are cultural remnants in our psychologies from this era of the capitalist separation and destruction of the commons.

Johnny Flynn: That’s a great way of putting it.

Peter Linebaugh: Well, we need much more work about it, I think, or I’d like to learn more about it, but Janet Neeson, I definitely recommend her.

Johnny Flynn: Would you say it’s a flaw in Marxism, that no one ever talks about how the worker is reproduced? It’s like the worker arrives at the factory to do the work or whatever. You know, do you think Marx overlooked the whole social reproduction? The stuff that was considered women’s work within the kind of capitalist system?

Peter Linebaugh: Johnny, you’re going to make me defensive. So, I think I’ve got to acknowledge that, because I have such admiration for Marx.

Johnny Flynn: Me too.

Peter Linebaugh: And he has so many enemies that to look at his limitations is… Well, it’s necessary and it’s true, he’s got a chapter on reproduction but it’s not social reproduction. In our era there have been such great debates from Maria Mies or Mariarosa Dalla Costa or Sylvia Federici or Margaret Benson, who have pointed and worked with this huge absence from Marx’s political economy, the other half of the human race.

Myself, I think what’s missing in so much of Marxism has depended on his political economy through the disparagement, on the one hand, of the philosophical anthropology of the young Marx, but also the neglect of (and even a failure to publish) the old Marx. Not all the ethnological manuscripts and notebooks have been published or translated. And they are about the commons, whether it’s the Russian obshchina or the peasant ‘mir’ or the Iroquois ‘longhouse’ here in Turtle Island.

Also Marx spent two months at the end of his life in Algeria and there he was investigating also the practices of the Algerian remnants of forms of Commoning. Now, all of this is not to say that just because he’s interested in commons, he’s therefore interested in women’s labour, but the definition of Marxism, I think, has to do with unpaid labour and that phrase that I think has really gotten in the way of many people’s thinking, which is free wage labour. They use freedom in contrast to slavery. I think that’s a hindrance to further thought because when it is labour of reproduction, of raising children, of her care work, whether it’s raising children, looking after the old or getting the breadwinner through the day, that labour is totally unpaid.

Johnny Flynn: What David Graeber, the late David Graeber, calls the bullshit jobs are paid for but the care work is disparaged.

Peter Linebaugh: His death, unexpected, is a great loss to us. He described bullshit jobs definitely. I haven’t read Bullshit Jobs but I did read Debt and I admire it.

Johnny Flynn: We were just speaking about the Jubilee too.

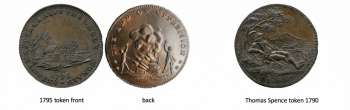

Tokens, used as coinage were a form of revolutionary messaging as highlighted in Red Round Globe Hot Burning by Peter Linebaugh.

Peter Linebaugh: I think Thomas Spence also confronted this issue of money and wanted to turn money or token into political coin.

Johnny Flynn: Incredible: class war coins. They’re all over your book, Red Round Globe Hot Burning. There are all those different coins in the book.

Peter Linebaugh: I like that [1795] one because the top one is a quote from the Irishman Oliver Goldsmith. ‘One only master grasps the whole domain’ and it shows this village that’s just wrecked and these trees that are dead and the squalid nature of the road. The other side of the coin is called The End of Oppression and it shows two people burning deeds, burning property deeds. So, it’s just like when a Zapatista showed up and led by women, they burnt the property deeds there in San Cristobal.

Peter Linebaugh interview: the Charter of the Forest

Johnny Flynn: You told a story about the Zapatistas where you said that you misunderstood Subcomandante Marcos about the Magna Carta, something like that, and then you ended up doing a whole Magna Carta book. Was that correct? I think I remember reading that and thought it was a pretty funny story.

Peter Linebaugh: You’ve got to use your own ignorance to advantage. I’m lousy at language. I don’t speak Irish or can’t pronounce it, same with Spanish and all other languages, so when I saw Subcomandante Marcos referring to Magna Carta, I thought, ‘Oh boy, this is the 1215 charter of liberty,’ but it wasn’t at all, it was the Mexican Constitution he was referring to. But, despite that mistake, it made me pay attention to the Mexican Constitution which was all against the ejido. And that had been the beginning in 1994 or the year before the ejido was removed from the Mexican Constitution: ‘no more commons’. That caused me to go think about the English Magna Carta, what had been its relationship to the commons? And as a result discovering its sister charter, the Charter of the Forest.

The Forest Charter of 1217 obliged the English king to give back the use of the forest to the people.

Johnny Flynn: You did very well, actually, because there was some great stuff about the Magna Carta. The Magna Carta Manifesto was brilliant. There’s a video of you on YouTube at Sherwood Forest talking about these great oaks, and you are almost channelling Spence or someone. You get into a real kind of rhetorical power.

Peter Linebaugh: It was like a dream to be in a place where it felt like Robin Hood was going to pop out somewhere and to be surrounded by all these powerful militants from all over the midlands of England, against fracking and for the preservation of the woodlands. There were some wonderful people there and also, Johnny, the most amazing trees I’ve ever seen.

Johnny Flynn: You said to be among these great oaks…

Peter Linebaugh: It was like out of a Hollywood fantasy movie. I expected these oaks to start talking or their limbs moving like arms at any moment.

Peter Linebaugh on thanatocracy

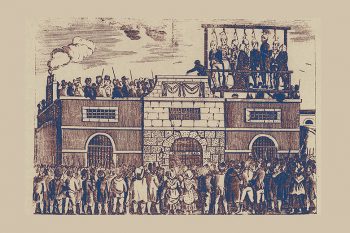

Johnny Flynn: Beginning with The London Hanged you talk about ‘thanatocracy’, which I presume means rule by the spectacle of death, or the threat of death or hanging and executions, as a way of disciplining the common folk who have been kicked off the commons. It’s in Red Round Globe Hot Burning as well, you talk about the thanatocracy. It seems like a key concept for you in the rise of capitalism: red in tooth and claw.

Peter Linebaugh: I’ll talk about it but then I want to know what you think about it, because thanatocracy, I guess it’s Greek, government by death, like you have democracy, government by the people. It comes from John Locke. He defined sovereignty as the ability to pass laws with the punishment of death, and so if that was his notion of sovereignty, that’s the Roman notion of sovereignty too. When Caesar is displaying himself in the city in a procession, he’s preceded by a person carrying a bundle of sticks and these sticks were the fasces and they sit with an axe among them, they indicated sovereignty and the axe was a tool of decapitation.

So capital punishment and the ability to murder or to kill another person was the essence both of the precessions of Caesar but also of John Locke and the foundation of the liberal era. The foundation of law was capital punishment. Of course I wanted to tie it into Marxism. Surplus value, as interest, rent or profit provides bankers, landlords and capitalists and entrepreneurs with their wealth, but it’s always at the expense of those whose value, that is their wages or their receipts of subsistence goods is reduced lower and lower and lower and lower until death arrives.

There is a constant reduction on the value of a human being and the value of work. In fact, work itself is deathly, as Marx showed in Chapter 10 of Capital with the story of Ann Walkley who died from overwork. I learned more about this last night from hearing Mike Stout talk about the struggle at the Homestead Steel Works in Pittsburgh, a factory that produced the steel for the world for a couple generations. He said between 15 and 20 people were killed every year at Homestead at these steelworks in Pittsburgh. And then this summer we saw the police knee on the neck of George Floyd, and this, again, was to demonstrate the power of police. And you look at the policeman’s face and you can see that he’s sort of taking satisfaction in his work, unlike a lot of executioners such as Jack Ketch, a lot of them do not take much satisfaction in that work and it leads to illness. So, there’s a spectrum, I think, from John Locke to George Floyd, and we also see it in the management of the coronavirus, of the pandemic, I think where African American people, poor people, old people are targeted in a kind of triage, an unspoken triage, are left to die, are left to be more susceptible to this disease, and certainly less able to obtain relief.

And then going back to the theories of capitalism in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, especially to Malthus, there is a new form of reasoning, of calculating the deaths numerically across a whole demographic spectrum, a whole society, and I think that method of reasoning had its origins in Ireland with the English conquest of Ireland, with Gregory King and William Petty of the Down Survey. People were beginning to calculate and enumerate populations as a whole. They were beginning to study social reproduction for a whole society. So some of them also anticipated and try to manage deaths. Who is going to starve and who won’t starve? Who is more likely to obtain, get a disease and who isn’t? And this is also, I think, related to thanatocracy. But mainly, of course, thanatocracy refers to capital punishment, which I define not just legally but as the punishment of capital, so it’s trying to broaden the meaning. Now, my question to you, Johnny, is if I had some different essays on this, which I’ve written over the years and I want to put together in a book, do you think I should call it Thanatocracy?

Johnny Flynn: I think it’s an extraordinarily suggestive concept. I think it’s brilliant. For me it gives me a good picture in my mind, everything I think about, the rise of capitalism and through your works I can get a really vivid picture of just the sheer brutality of the enterprise, because often as leftists, you’re always on the back foot. People say, ‘Oh, what about Stalin? What about the brutality of the Soviet experiment or whatever?’ You’re like, ‘Absolutely. I’m not denying it. But let’s also concentrate on this extraordinarily brutal couple of hundred years which is just unparalleled in the terms of the amount of savagery.’ I think thanatocracy is a theme in your works from The London Hanged to tales like The Many-Headed Hydra: such as when Francis Bacon is talking so genocidally about working class people and plebeians.

COVID and the U.S. election from the perspective of Peter Linebaugh

Johnny Flynn: It’s interesting you just brought up the issue of quarantines and COVID. I actually had that as a kind of second question I was going to ask you. Did you think there was any relation to the idea that how people are almost expendable now under this plague system? Does it in any way relate to what you discussed as thanatocracy?

Peter Linebaugh: It’s already part of a mainstream debate in this election year here in the USA. How many lives did Trump sacrifice? Is it 100,000 or is it tens of thousands? There’s sort of a debate, but the assumption in both of them is that those policies led to deaths. But what’s missing from that debate, at least in the mainstream, is those deaths were socially targeted towards a population that’s either dangerous or useless from a standpoint of producing surplus value, from the standpoint of producing wealth or riches for the ruling class. Trump has no use for nursing homes. He has no use for the urban proletariat of cities, and is willing to … I was going to say sacrifice, but it’s more than that. Well, I don’t want to get into his psychology, but politically the morbidity of the coronavirus targets African American, brown people, immigrants and the elderly. That’s common public health knowledge.

What makes a criminal?

Johnny Flynn: I was reading Stop, Thief! where you have the published, ‘Karl Marx, the Theft of Wood, and Working-Class Composition’, and discuss the essays that alerted or turned Marx towards a more class analysis eventually. You also discuss criminology and especially in The London Hanged and Red Round Globe Hot Burning, it’s like you turn the tables on what is called the criminal and criminality. You basically say the theft of commons was the crime and then this whole architecture of law was built in order to defend that. And then criminalise the customs of the people who were commoners. Let’s say if you worked in the docks you had customary perquisites, you took a certain amount of coffee or tobacco: that was criminalized. You had the police there to insure that. So now we have this huge architecture of law, this carceral state with the police at the front of it. So I like in your work how you subvert what was traditional in criminology to go, ‘Actually, the real criminals are …’ It’s a bit like the peasant ditty of prison for the man or woman who steals the goose from off the common, but the greater villain is let loose, who steals the common from the goose. I think that’s a great kind of aspect of your work. It’s only one aspect but it’s a very important one because you’re thinking about the whole of capitalism. It really wrong-foots the apologists of capitalism. So if you could talk a little bit about that. That seems to be one of your early kind of entries into this work of yours was that kind of thinking about the whole idea of criminalisation.

Peter Linebaugh: This goes back for me to what I learned from people, other historians like Edward Thompson or Eric Hobsbawn or George Rudé who were writing in the early 1960s. Also, in the early 1960s in the USA there were the municipal uprisings that began in, let’s say, 1962 or ’63 in Harlem and Rochester and then expanded to Detroit, to Watts, and these were rebellions against white supremacy, rebellions against poverty, against slum housing conditions and against a future with no hope, basically no future at all. Those rebellions led to a huge counter-movement of law and order, where it was assumed the only law and order was the law and order of property and of U.S. entrepreneurial individualism. In California it is Ed Meese who becomes the attorney general for Ronald Reagan who then, years later, becomes president under that cultural sign of law and order, which a couple months ago, Trump dragged out and tried to use against the protests of the murder of George Floyd.

That was the context back in the ’60s, this demonization of African American people, and the man who showed that to me and has showed it to the world as being a phony, slanderous labelling was Malcolm X, Malcolm Little, who himself had been a criminal, a burglar, who did time in prison and who learned in prison in the late 1940s, perhaps from Wobbly teachers in the Massachusetts prison. Anyway, over the years, he begins to turn the tables. So, all you have to do is see what he does and then do it yourself. And I wasn’t the only one, like the other historians. I’m trying to say that my knowledge came out of the movement. What I learned was already being put into practice by the African American working class in the USA. And of course it’s worldwide.

You in Ireland would know it, like in South Africa or India, the different forms of humiliation and degradation which the ruling class always uses, whether it has to do with table manners or whether it has to do with racism, whether it has to do with educational opportunities or living conditions. People from colonial settings learn how to be compliant and how to have that double consciousness, of how to get along with the man, how to get along with authority on the one hand and on the other hand it’s ‘save yourself’, to have some kind of dignity, some kind of solidarity with others who suffer. So taking that quatrain that you quoted: the law locks up the man or woman who steals the goose from off the common but lets the greater villain loose who steels the common from the goose. There’s a story in there that Foucault told us about the carceral society but also in there is the story of Malcolm X, the story of how the prison can become the university of liberation. This happened of course with H-Block in Ireland.

The ruling class will always try to criminalize its opponents and when it comes to property or to subsistence life, then it gets very desperate, and then the famine, early death, morbidity arises. But in Red Round Globe Hot Burning, I got two chapters at least about the criminalization of the commons. Usually we think of the commons in rural or agrarian settings or settings of the woodlands or wetlands or pasture but what these two chapters try to help us see is that the so-called criminality in the city is also like a form of opposition to enclosure, forms of opposition that are analogous to the estovers, the pannage, the herbage, the agistments, these old concepts of the agrarian commons. So that’s what I was trying to do.

Johnny Flynn: You were talking about getting radicalized in prison. I love your idea that maybe Thomas Spence met Edward Despard in prison. I was thinking about that for ages afterwards, just imagining the two of them meeting in prison, because Spence was imprisoned at the same time as the Mutineers or the 1797 naval mutiny. And weren’t the United Irish involved in it?

Peter Linebaugh: Yeah, Valentine Joyce.

Edward Despard and Thomas Spence

Johnny Flynn: When they were in prison, Despard was in prison then as well, wasn’t he? Was he locked up?

Peter Linebaugh: He was locked up in those cells in the Clerkenwell or the Stille. They called it the Bastille or the Stille for short. But Despard also had been in Shrewsbury Prison, another new prison, and his life was a time of prison construction. I think Spence had been there in Shrewsbury Prison, or I know he was, but I’ve wrote the Shrewsbury Record Office because I didn’t have the wherewithal to make a personal visit, because you’re always dependent on the generosity of the archivist as a historian, but they couldn’t date an overlap between Spence and Despard in Shrewsbury Prison. But that’s kind of a vain search, you know, Johnny? They wouldn’t know about each other. Like I never met Malcolm X even though he taught me, you know what I mean? Certainly, there would be plenty of songs that Despard would know.

And I think Spence was very expressive and Despard was not. Despard didn’t write much. Spence wrote quite a bit. That was his method of communication. That, then chalking and music. Despard was a military man. He was a leader and could see many different forces at play at once. He saw the city as a target, as an insurrectionist. He’s more like Auguste Blanqui in French revolutionary history. I don’t know Irish politics well enough to know in the Republican tradition who are those who are most apt to go for another Easter Rising, of just attacking, say, the post office as a first step. But Despard certainly had a tradition of this. He was a skilled artilleryman because of his knowledge of geometry, but he was good at: ‘Where do you put a cannon? What do you point it at? How do you get it there?’ This is largely a question of organizing livestock and human beings to move ordinance around. That’s a big job of labour. And so he in a way was a manager, you know what I mean? We have to look at his life, what he was trained at doing. Then, when he’s jailed in prison all through the 1790s in one prison after another, Newgate, Shrewsbury, the Tower, the Coldbath, Stille and several others, he meets a lot of people and they want to shut him up. They want to prevent him from getting food. They want to make sure that there’s no glass in his windows. They want to make sure that the door doesn’t go down to the floor, so that wind and snow and rain can flood his cell. They want to work on his malaria and see him perish.

Peter Linebaugh: That’s where Kate is so helpful in organizing not just her alone but the relatives, the wives, the women of other political prisoners. They formed support groups, and I think as you emphasise in a review you wrote, she was intrepid.

Johnny Flynn: She put the fear of God in them.

Peter Linebaugh: She did. Horatio Nelson, she’d speak back to him. These people lived in fear of this woman’s tongue and of her righteousness, quoting her in parliament and also trying to subvert her by saying a black person could not write good grammar.

Johnny Flynn: That they were too well written or something.

Peter Linebaugh: When they say, ‘Oh, public schooling,’ what they mean is, ‘You’ve got to come and learn the way we spell, the way we think, the way we write.’ Anyway, there she is, helping to write his last speech at the gallows.

Johnny Flynn: That speech at the gallows, that’s a good speech. I like that one. She probably must have written the bulk of that, as he doesn’t seem to be the man of words, was he?

Peter Linebaugh: I think he learned that you want to put things in threes.

Johnny Flynn: I love your rumination at the end of the book, ‘What is the human race?’ You end the book with these real bravura chapters, it’s like the red crested bird and the black duck. Allegorical kinds of interesting mise en scene, like the guy who decided he was sick of urban life and went over to live with a Native American and has come back and is telling this story, and how you connected that story with the Irish and the Native Americans. It’s a fascinating chapter, that one. And then ‘what is the human race?’ is brilliant way to end the book because it brings all the themes together.

Peter Linebaugh: Well, the Irish defeat in 1798 meant a lot. Thomas Jefferson would not have been elected president without the effort of former United Irishmen, who were editors of newspapers in South Carolina, North Carolina. The splendid historian of Ireland taught me that.

Johnny Flynn: Who is that, Kevin Whelan?

Peter Linebaugh: This book could not have been written without the writings of very fine Irish scholars and historians and poets, especially from the Field Day tendency. Kevin Whelan is a big part of it and I was very grateful to him and others who invited me to Ireland at the time of the Good Friday Agreement and we had a grand meeting on the commemoration, the bicentennial of the 1798 rebellion. So I really want to thank them very much. And also Patrick Bresnahan at Maynooth who wrote an appreciation of Red Round Globe Hot Burning in the journal Antipode.

We let a point slide by that I want to return to, which was Catherine Despard was active in preventing the foundation of a panopticon. I just wanted to emphasize that. That was one of Jeremy Bentham’s favourite projects.

Johnny Flynn: I’ve one last question, which is about the Diggers and Winstanley and, ‘the earth is a common treasury for all’. If I understand your book correctly, Winstanley and the Diggers, True Levellers, the Ranters, they come from an earlier tradition as well, like maybe Wat Tyler? And the message from the English Revolution, the radical message, stays alive. So when Edward Despard is accused by the prosecutor, Lord Ellenborough, of being a Leveller, of believing in this equality, this terrible stuff. This is Winstanley’s message back again. It’s come back through Edward Despard and his revolutionary conspiracy essentially. It’s gone around the Atlantic and it’s come back as this conspiracy to restore the commons.

Peter Linebaugh: And Despard is only one of the vectors. There are many others.

Johnny Flynn: It’s fascinating that, like you said in the book, that stories help keep alive the memory of defeats or help us understand defeats, and I think your book kind of does that. If you took your book as a story, it pieces together all these things and all the different things happening at the time and it helps us make sense of defeats, but defeats aren’t the end of the story. In the twenty-first century we could still restore the commons, you know?

Peter Linebaugh: I think the crossroads isn’t something that just happened back then. It’s still here, and the alternatives are for us to revive.