In this post, I continue the draft of sections of my forthcoming book, “Marxian Economics: An Introduction.” The first five posts (here, here, here, here, and here) will serve as the basis for Chapter 1, Marxian Economics Today. The next six (here, here, here, here, here, and here) are for Chapter 2, Marxian Economics Versus Mainstream Economics. This post (following on a previous one) is for Chapter 3, Toward a Critique of Political Economy.

The necessary disclosure: these are merely drafts of sections of the book, some rougher or more preliminary than others. Right now, I’m just trying to get them done in some form. They will all be extensively revised and rewritten in preparing the final book manuscript.

-Hegel

It is difficult to fully understand the Marxian critique of political economy without some understanding of Hegel. No less an authority than Lenin wrote that “it is impossible completely to understand Marx’s Capital, and especially its first chapter, without having thoroughly studied and understood the whole of Hegel’s Logic.” Marx himself wrote

I therefore openly avowed myself the pupil of that mighty thinker, and even here and there, in the chapter on the theory of value, coquetted with the modes of expression peculiar to him.

Those are the two major reasons for keeping Hegel in mind: because Marx, like many young German intellectuals in the 1830s and 1840s, started with Hegel; and because, many years later, Marx’s critique of political economy was still influenced by his theoretical encounter with Hegel.*

But, of course, that makes understanding the movement toward the Marxian critique of political economy a bit difficult for contemporary readers, who generally aren’t familiar with Hegel’s writings. So, in this section, I want to present a brief summary of Hegel’s philosophy. But, I caution readers, this should not be taken to be a presentation of all aspects of Hegel’s thought. We only want to examine Hegel to the extent that it aids our comprehension of Marx’s theoretical journey and his later critique of political economy.

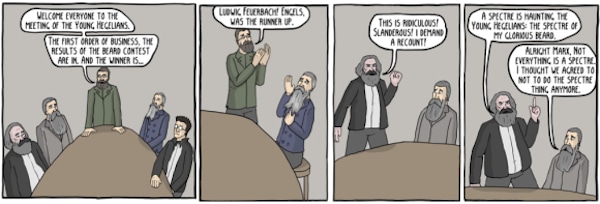

In his twenties, Marx, along with other young German intellectuals (including Ruge, Bruno Bauer, and Ludwig Feuerbach), formed a loose grouping called, variously, the Young Hegelians or the Left Hegelians. In their discussions and debates, these young thinkers sought both to draw on Hegel’s philosophy and to radicalize it, aiming their attacks especially at religion and the German political system.** Later, they turned their radical critique on Hegel’s philosophy itself.

So, what was it in Hegel’s thought that was so influential for Marx and the other Young Hegelians? One are is particularly important: the theory of knowledge and, closely related, the philosophy of history.

On the first point, Hegel’s view was that the two previous traditions—of René Descartes and Immanuel Kant—got it wrong. Descartes argued that it was impossible to know things as they appear to us (phenomena) but only things as they are in themselves (noumena). Experience was deceptive. Hence, his focus on reason, which alone can provide certainty about the world. Kant posited exactly the opposite—that it was possible to know things as they appeared to us but not their essences, things as they are in themselves. Therefore, science was only capable of providing knowledge of the appearances of things, of empirical experiences and observations about nature; morality and religion operated in the unknowable realm of things in themselves.

Hegel’s great contribution was to solve the problem and affirm what both Descartes and Kant denied. For him, history was an unfolding of the mind (Absolute Spirit) coming to know itself as phenomenon, to the point of its full development, when it is aware of itself as it is, as noumenon. In other words, the consciousness of things as they appear to us leads to knowledge of the essence of things. At the end of the process, when the object has been fully “spiritualized” by successive cycles of consciousness’s experience, consciousness will fully know the object and at the same time fully recognize that the object is none other than itself. That is the end of history.

How does this historical process work? How does the mind or Absolute Spirit pass through successive stages until it reaches full awareness? That’s where the dialectic comes in. According to Hegel (especially the Phenomenology of Mind), human understanding passes through a movement that is characterized by an initial thesis (e.g., being) that passes into its opposite (e.g., nothingness), which entails a contradiction that is resolved by a third moment (e.g., becoming), which is the positive result of that opposition. For Hegel, this process of thesis-antithesis-synthesis (or, as it is sometimes referred to, abstract-negative-concrete) is both a logical process (the development of philosophical categories) and a chronological process (the development of society), which leads to greater understanding or universality (in both philosophy and in social institutions such as religion and politics), eventually leading to complete self-understanding—the end of history.

What Marx and the other Young Hegelians took from Hegel was a method and language that allowed them to challenge tradition and the existing order: a focus on history and a stress on flux, change, contradiction, movement, process, and so forth.

But they also turned their critical graze on the more conservative dimensions of Hegel’s philosophy. For example, Feuerbach (in The Essence of Christianity, published in 1841) argued that Hegel’s Absolute Spirit was nothing more than deceased spirit of theology, that is, it was still an inverted world consciousness. Instead, for Feuerbach, God was the outward projection of people’s inward nature. Men and women were “alienated” from their human essence in and through religion—because they cast all their human powers onto a deity, instead of assuming them as their own. The goal, then, was to change consciousness by becoming aware of that self-alienation, through critique.

Marx, in particular, considered Feuerbach’s critique to be an important step beyond Hegel. Ultimately, however, he rejected the way Feuerbach formulated the problem (as individuals separated from their human essence, outside of society) and settled his account with the eleven “Theses on Feuerbach,” the last of which has become the most famous:

The philosophers have only interpreted the world, in various ways; the point is to change it.

———

*Even though I insist on the idea that a basic understanding of Hegel is necessary for understanding Marx’s theoretical journey, it is also possible to overstate the case. Marx’s method is neither a straightforward application nor a simple reversal of the Hegelian dialectic. But the time he wrote Capital, Marx had criticized and moved far beyond Hegel’s philosophy.

**At the time (beginning in 1840), Germany was governed by a new king, Frederick William IV, who undermined his promise of political reform by curtailing political freedom and religious tolerance. For the Young Hegelians, this was a real step backward in terms of following the rest of Europe (especially Britain and France) in modernizing political institutions and expanding the realm of freedom. And it was key to their eventual break from Hegel, since according to Hegel’s philosophy the Prussian state represented the fulfillment of history. (The contemporary equivalent is Francis Fukuyama’s famous book The End of History and the Last Man (1992), in which he argued that “not just. . .the passing of a particular period of post-war history, but the end of history as such: That is, the end-point of mankind’s ideological evolution and the universalization of Western liberal democracy as the final form of human government.”