El Maizal is a rural commune between the centrally-located states of Lara and Portuguesa, with a deep commitment to Chávez’s project as expressed in the “commune or nothing” slogan. Now, in early 2021, these communards are promoting what will become the Hugo Chávez Communal City. This new democratic construction will bring together seven communes in a process that, in the words of communard Windely Matos “puts the people and not capital in the center of territorial organization.”

Here we interview Jennifer Lemus and José Luis Sifontes, two committed communards who walk us through the political and theoretical genesis of this new communal city. Lemus is a key figure in the organization of the Hugo Chávez Communal City, while Sifontes is a communard who left the comforts of Caracas to live in El Maizal Commune.

(Note: In the Bolivarian process, the term “territorial” distinguishes sectorial organizations such as those comprised of youth or workers, from grassroots and community-based organizations.)

If we understand the commune as the basis for democratizing society in economic, political, and social terms, what is the role of the communal city?

José Luis Sifontes: The first thing that we should do is understand that communal cities are not an end in themselves. Communal cities are part of a progressive process of popular organization. With Chávez’s arrival to power, the political sphere’s logic changed radically through popular participation.

Before Chávez the asociaciones de vecinos [neighborhood associations] were the main grassroots organizational structure, but they were very limited. The asambleas de barrio [assemblies in some Caracas barrios] also precede Chávez. They were seeds of what was to come.

When Chávez arrived, territorial work committees began to organize; comités de tierra urbana [urban land committees], mesas técnicas de agua[technical water committees], and comités de salud [healthcare committees] were all born in the early days of the Bolivarian Revolution. Those were the first steps towards a broad popular organization in the territory aimed at solving the problems of the people in the communities.

Communal councils–which brought together the work committees–emerged in that context. In fact, what Chávez did was to provide a legal framework to the various expressions of popular organization. That is how the Communal Council Law came into being in 2006. In other words, communal councils are part of a process of popular organization with a profoundly democratic character.

In this process, the need to form communes emerged [in 2009]. Communes are spaces for integrating several communal councils. The communes, like the communal councils, are territorial: they are the government of the people.

Chávez proposed the idea of an integrated system of communes as the seed that would become Bolivarian socialism. After going from communal councils to communes, the next step in this progressive process is building the communal city.

The communal city is the aggregation of several communes in the territory to configure an instance of self-government that is based on the realities of the people.

Of course, the key to all this is the decision-making process through which the people determine their destiny in assemblies, thus overcoming old practices of representation.

What is the point of making a communal city? To continue advancing towards democratizing society from the grassroots.

I believe that it is very important to understand that Bolivarian socialism is built from below, from the bases. It is not imposed by decree, and that is why it must express itself as a government that responds to the interests of the people.

The communal government–constituted by the people, by the pueblo, by the spokespeople of the communal councils and the communes–will create communal cities with an even wider horizon: the new communal state.

In other words, the communal city cannot be understood as an end in itself. The communal city is part of a progressive process. After that comes the grouping of various communal cities, the confederation of communes… and all this will give birth to the new communal state, which is the strategic objective!

Jennifer Lemus: Indeed, in technical terms, a communal city is the aggregation of several communes in the territory. However, beyond that, it is a space for exercising self-government and sovereignty. But I should qualify this: for us communards, when we talk about sovereignty, we are speaking about the people taking the reins of the economic, political and social affairs in the territory. In two words: popular power.

The commune–and the communal city by extension–is the space of encounter and empowerment of people who share social, cultural, economic and political characteristics and live in the territory. In the commune we meet, we identify ourselves as part of a community, we dream and we build. Through expanding this space of identification, the communal city was born.

Communal cities are a legacy of Comandante Chávez, an important link in his “all power to the pueblo” conception.

For us, the communal city also represents an opportunity to organize ourselves and build power from below among equals. Additionally, we are pouring our energy into the collective making of the Hugo Chávez Communal City because we believe that communal cities are the foundation of the communal state, which is inextricably linked with socialism and is the way to achieve what Chávez called “supreme happiness.”

Direct democracy is central to the Chavista project. Depicted is an assembly at El Maizal Commune. (Gerardo Rojas)

What does the El Maizal Commune aim to achieve in constructing the Hugo Chávez Communal City?

Lemus: El Maizal Commune developed the objective of building the communal city some three years ago because we aspire to contribute to the construction of the communal state from our territory.

Now we are in the process of formalizing the foundation of the Hugo Chávez Communal City, which will initially be made up of seven communes and eight communal councils. Formation and debate are at the core of the process: we are defining our objectives and our collective desires in local assemblies. Additionally, these debates will contribute to the [soon to be debated communal city] law.

The economic problem has been very much present in these assemblies. While it is true that Venezuela is going through a profound crisis, there is great potential if the country’s resources are aligned with the communal project. If this were to happen, we could solve most of our problems.

For this reason, we are working so that all the vital revolutionary forces come together. Certainly, we have differences and contradictions, but this is the time to bring our struggles together and unify our forces.

In the communal city we–the poor, the humble, among equals–will all come together under the aegis of Chávez’s project.

From there, from the communal city, we also hope to contribute to the Communard Union. With its political and economic muscle, this union will become an important tool for consolidating popular power from the bases, from the communal project, with all its implications.

Sifontes: As Jennifer said, our first goal is to carry out Chávez’s plan of making the communal state, which he saw as the final goal on the path to socialism. He bequeathed to us “commune or nothing” as a mandate.

Chávez argued that the old bourgeois state would wither to the extent that organized people would overcome it and make the communal project real. Over time, a new communal state representing the majority is supposed to replace the old bourgeois state.

To advance popular organization, it is necessary that the people come together as equals and design plans for achieving common objectives. For this to happen, it is key to understand that we have the same needs and problems, the same cultural milieu. The commune is the space for weaving our dreams together.

Chávez proposed a reorganization of the territory through communes, which would transcend boundaries established by old laws (particularly the borders of townships and states). In his way of seeing things, the geography of organization should be defined by the people and the cultural, economic, and social relationships that they established over time. The boundaries of a communal organization should not be defined by an institution.

In other words, Chávez imagined a new political geography democratically defined by the people. The communal cities are an expression of this new configuration.

As we move toward the communal city–the space for the commons–and when we vote in its foundational referendum, we will be approving a new “geopolitics.” The communal city will be the rebirth of the territory in the people’s hands.

The first meeting for creating the Hugo Chávez Commune in the Lara and Portuguesa states was held on Saturday, January 9. (El Maizal Commune)

The National Assembly is set to promote at least two laws relating to the communes: the law of Communal Cities and the Law of the Communal Parliament. While some celebrate the initiative, others are more cautious since the new bills may subordinate communes to townships in the state’s pyramidal structure, thereby transferring institutional responsibilities to the communes [garbage collection, gas distribution, etc.]. What do you think about this?

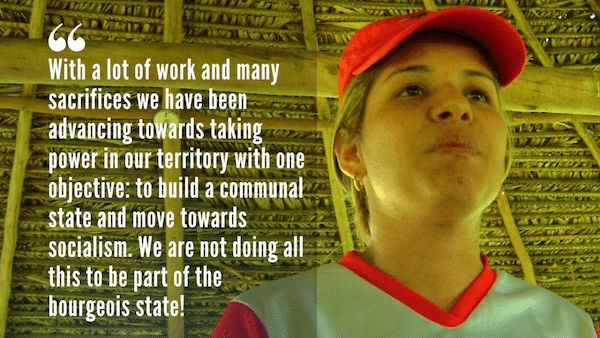

Lemus: With a lot of work and many sacrifices we have been advancing toward taking power in our territory with one objective: to build a communal state and move towards socialism. We are not doing all this to be another part of the bourgeois state!

As an offshoot of the new state, we must assume new responsibilities in our territory, but this does not go hand in hand with those proposals that advocate transferring problems that the institutions cannot solve to the communes. Instead, we think that the communes (and the communal cities) should characterize the territory and identify common plans, objectives and responsibilities. We know best what our needs are and we will solve them communaly.

The communal city does not aim to eliminate town halls, regional governments or other institutions. Instead, from the bases, we are building the new state and we aspire to transcend the old structures.

Sifontes: When it comes to new laws, we should be wary of reformism. It is troubling how some sectors within the Bolivarian process ignore Chávez’s proposal for the communal state. We have to combat these tendencies because the new state’s birth is imperative.

We live under the structures of a bourgeois state that does not obey the people’s common interests and is designed to reproduce exploitation. That’s the state we have today.

However, the new can be glimpsed in the Constitution, and it is fully present in Chávez’s conception of the commune. The National Assembly should debate the full incorporation of the commune into the Constitution of the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela. With this in mind, we propose a national consulting process. That would be a way of ensuring that the new laws are really borne from the people, the commune-builders, and that they obey Comandante Chávez’s guidelines and not reformism.

The Communard Union–a national space bringing communes together and promoting them–is sure to have a debate about this. At El Maizal Commune, the debate will be promoted in the Commune’s School of Political, Ideological, and Technical Formation, but also in the educational spaces of the Communard Union. From there, from the bases, we are going to generate debates and proposals.

As for the Law of Communal Cities that the National Assembly will develop, it is important to understand the communal cities are not an end in themselves and that they aren’t appendices of the existing institutions. As I said before, a communal city is one step in the integrated communes system towards the communal state, the state of the people.

Now, as we speak, there are proposals circulating based on highly bureaucratic conceptions that would impose external administrative procedures and institutional requirements in the making of communal cities, which break with participative democracy.

The conditions in every communal territory vary a great deal. Some are urban, others rural; some are productive, others service-oriented. Additionally, some communes comply with the central government’s norms whereas others have not been able to do so. However, this should not be a barrier for the construction of a communal city. In fact, the spirit of community and solidarity within a communal city should lead to cooperation between communes. This would in turn strengthen self-government and the process of compliance with other norms.

It would be a mistake to put up barriers to the promotion of communal cities, to put “legality” as an obstacle in the advancement of communal organization.

It is also not correct to decree communal cities. The Ministry of Communes can guide or accompany communal construction, as can local and regional governments and the [PSUV] party. However, the initiative for making communal cities resides in the people.

The communes, the communal cities, and ultimately the communal state must be a creation of the masses. The communal project belongs to the people, not to the institutions. That should be very clear. The commune is not an appendix of the institutions and cannot be conditioned by institutional logic.

We also have to be vigilant about the Law of the Communal Parliament, which will be discussed at the National Assembly as well. This is important because some want to fit the commune into the bourgeois state’s structures.

According to the Kelsen pyramid, there is a parliamentary organization on a national level (the National Assembly), below that are the legislative bodies at the regional level, and under that the municipal councils. Now, as Jennifer points out, we should be wary of tendencies that want to fit communal councils and communes in that structure and under the municipal councils. Doing so would be a serious mistake.

If the communal parliaments were to enter the Kelsen pyramid, they would be subsumed by the old state’s structures.

In our view, the Law of the Communal Parliament must progressively open spaces for the integrated system of communes while becoming a vehicle to the new communal state.

The process of commune-building (and in fact any revolutionary process) necessarily generates contradictions, both internal and external. What are the main contradictions and debates right now? How do you work to resolve them and advance towards collective emancipation?

Sifontes: As we speak, the main contradiction is with the party [PSUV] and the state’s institutions. The question is: who is going to promote popular organization and shape the new communal state? In this regard, there is a latent internal debate regarding the need to overcome the old bourgeois state. When it comes to doing so, there is resistance and even entrenchment. In our grassroots debates, we argue in favor of the new communal state.

As El Maizal Commune we have political responsibilities, and we must follow revolutionary principles and Chávez’s project. With this in mind, our task is not to promote our particular vision; our obligation is to promote debate.

From El Maizal Commune we are encouraging those debates. On Saturday [January 9] we had the first assembly and yesterday [Tuesday, January 12] the second meeting of the Hugo Chávez Communal City Promotion Brigade. Both happened in Sarare’s Sucre Mission university seat [a space in Lara state, recovered by the commune].

Many people participated in yesterday’s meeting. It included the local mayor, town hall directors, the local head of the PSUV, and, most importantly, the communes’ spokespeople and communards from the area. In the meetings, there was a debate and some obstacles emerged. However, the democratic and communal spirit overcame the institutional tendencies. The majority prevailed.

The agreements include a plan for visiting the territories [beginning Thursday, January 14] and a plan for encouraging debate and formation with one main goal: drafting a proposal for forming the communal city. We will also send that proposal to the National Assembly. In so doing, we are abiding by one of Chávez’s slogans: Sólo el pueblo salva al pueblo [Only the people will save the people].

We are defenders of Chávez’s legacy, the sons and daughters of Chávez, and those who believe in “commune or nothing!”

Lemus: Indeed, there are a lot of contradictions. However, we have a single historical objective, constructing socialism, and we will give everything to achieve it.

I believe that the key to overcoming contradictions is listening to Chávez. Chávez was our school, and we still have much to learn from him. Chávez can show the way forward.

Additionally, an important way to resolve contradictions here, in El Maizal Commune, is by setting an example and working hard every day. In so doing, we are building a new political, economic and social model with the people–a model that is not paternalistic and from above. A model of solidarity and integration among equals.

In our commune, there are many of us who get up very early every day with a very clear objective: building socialism through communal means. We are convinced that only the people will save the people. That motto is dear to our hearts.

From El Maizal Commune and the soon to be Hugo Chávez Communal City, we are convinced that the only way to get out of this quagmire is by working with the people who continue to believe in Chávez’s legacy. But it is also up to us to convince others that Chávez’s dream is not just a dream, that there are people working to make that dream a reality.

I am happy to say that in the meetings and assemblies to shape the new communal city, we see many enthusiastic and committed people with a desire to move forward together.

We are lighting Hugo Chávez’s flame again in every corner of our territory, and we are sure that in the coming months we will be able to say that the Hugo Chávez Communal City is not simply a project, a dream, it is a reality. Furthermore, we are convinced that the flame will spread with the work of the Communard Union.

This brings us back to Chávez. To conclude, I would like to ask you about El Maizal Commune’s efforts to recover and revive his revolutionary proposal.

Sifontes: It concerns us that Chávez’s project is being abandoned. This year we are going to promote a communication campaign to recover the people’s Chávez: the Chávez that bequeathed us the project of creating the communal state.

Chávez is conjured up for each electoral campaign, but many have shelved his program. Abandoning the project plus corruption, bureaucratism and other deviations generates popular discontent towards the revolutionary process and even towards the figure of Chávez!

This is happening in our families, among our neighbors, etc. Of course, imperialism’s criminal sanctions and the pandemic also harm us, but at the end of the day, it is our duty to recuperate the people’s affection for the popular Chávez. To give you an example, while it is true that Chavismo won the majority in the parliamentary elections [on December 6, 2020], it is up to us to really analyze those results.

We must recover the popular Chavismo and authentic Chavismo. It is up to the Chavista grassroots to salvage his legacy from inefficiency, indifference, and corruption. Chavismo cannot tolerate inefficiency and corruption. To be Chavista is to be honest and to believe in the pueblo, not to benefit from resources that belong to the people… and we at El Maizal have the moral authority to say so!

This year we will advance in rescuing the popular Chávez–our Chávez, the one who belongs to the pueblo!