A Black medical truth-teller traces the link between a 1793 yellow fever epidemic and today’s coronavirus racial disparities.

The impact of the coronavirus pandemic has further exposed the glaring disparities between racialized groups, especially African Americans and White people.

At the start of the crisis in spring 2020, Midwestern states such as Wisconsin and Illinois, states that rank poorly in terms of quality of life for African Americans, and both North and South Carolina–Southern states with significant Black populations–had disproportionately higher rates of coronavirus cases and deaths among Black residents than White residents. Public health officials warned Americans that these disparities would reveal how medical racism, poverty, co-morbidities and labor conditions combine to harm African Americans.

They were not being hyperbolic in declaring medical racism a public health crisis.

Medical racism is not a new phenomenon. It did not start with either the Tuskegee syphilis study (an unethical experiment from 1932 to 1972 that the U.S. Public Health Service commissioned to study the effects of syphilis on 600 Black men in Alabama) or Henrietta Lacks, the mid-20th-century Black woman suffering from cancer whose cells became the first immortalized cell line in history. The origins stretch back centuries and created a system of belief and practice that allowed doctors to place blame on Black people for not having the same health outcomes as White people.

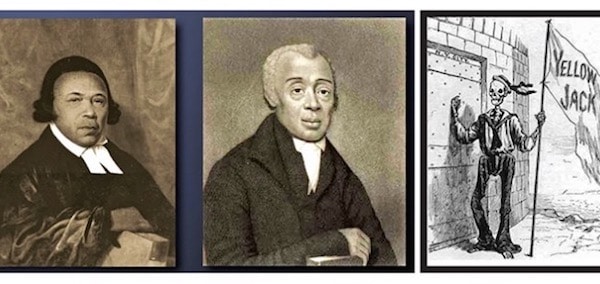

In fact, the first exposé on the dangers of medical racism emerged during a pandemic that ravaged Philadelphia just years after the founding of the nation. In 1793, there was a yellow fever outbreak and Philadelphians were dying in large numbers. Physicians were overworked. Gravediggers were running out of space, and residents were panicked.

One of the country’s leading physicians and abolitionists, Benjamin Rush, asked Ministers Richard Allen and Absalom Jones, and Black entrepreneur William Gray, to call upon Black residents to assist in the effort to help end the yellow fever epidemic. Believing that Black people were more immune to it, Rush petitioned the leaders to have their community provide care and essential services for the larger White population. Allen and Jones protested, informing Rush that African Americans in the city were not only infected with the viral disease, but also dying of it in great numbers. Rush kept pressing and eventually the men agreed to solicit help from African Americans to stem the tide of the virus by performing labor as caregivers, grave diggers, body collectors, housekeepers and trash collectors.

Black Philadelphians answered the call. They went to work as essential workers on the front line. Soon, their bodies were compromised because of the labor they performed. As a result, these Black workers began to fall victim to yellow fever. That year, the epidemic killed 5,000 Philadelphians. Black Philadelphians made up 10 percent of the dead, even though they were only 6 percent of the city’s population.

The disproportionate death toll exposed the deadly consequences of poverty, exploitative and dangerous labor conditions and false beliefs about biological difference. The fact that Black people had to live and work in isolated environments with infected patients, touch diseased cadavers, enter spaces to clean where the sick emitted bodily fluids and then return to their racially segregated communities after providing these services created the perfect conditions for the virus to thrive.

In fact, Allen almost died after contracting the disease. And then he read the work of prominent publisher Mathew Carey, who wrote a pamphlet condemning Black workers in 1793. “A Short Account of the Malignant Fever, Lately Prevalent in Philadelphia: With a Statement of the Proceedings that Took Place on the Subject in Different Parts of the United States” depicted Black workers as criminal and pathological. Carey accused Black workers of looting the homes of their charges, robbing the dead of their valuables and essentially profiteering from the disease.

After Carey published two more reprints, Allen and Jones located a prominent publishing house, William W. Woodward, to publish their retort and correct the record. The result was the first political tract against medical racism:

Narratives of the Proceedings of the Black People During the Late Awful Calamity in Philadelphia, in the year 1793: and a Refutation of Some Censures, Thrown Upon Them in Some Late Publications.

After a year of working to recruit Black citizens to help the city, which was devastated by disease, Allen and Jones had to shoulder the burden of researching and collecting data to refute Rush’s mistaken belief about Black people’s immunity to yellow fever and defend the Black community against Carey’s charges of immorality and criminality. They did so with hard facts and quantitative data, providing statistical evidence on Black people’s deaths.

Anti-Black racism continued to manifest in medical practices during the 1800s. Consider Samuel Cartwright’s use of the spirometer, a medical instrument designed to assess lung capacity. During the antebellum era, Cartwright, an enslaver, physician and an adherent to the idea that Black and White people represented two different species, found that Black people had lower lung capacity than White people. He surmised this was objective evidence of Black people’s biological inferiority. What he did not consider (or perhaps he did and did not care) was how cramped living quarters with little to no ventilation or insulation from the environment put enslaved people, the subjects of his experiments, at higher risk for respiratory conditions than White people.

By the 20th century, Black Americans were still suffering the effects of medical racism. Black women and girls in the South during the 1950s and 1960s received hysterectomies without their knowledge or consent. Infamously, as the Tuskegee experiment and Lacks case revealed, Black Americans were either neglected or exploited by institutions, both governmental and medical, that were supposed to prioritize their care. Black people’s mistrust was not born of superstitions, but originated in the ways they had been treated so callously by physicians.

From the 18th century until now, African Americans were more likely to suffer because of the social determinants of health and an anti-Black bias that permeated the medical field.

Thankfully, a number of prominent organizations such as the American Medical Association, the American College of Obstetricians of Gynecologists and the March of Dimes have declared medical racism a public health crisis. These organizations now recognize the ideas advanced over two centuries ago by Allen and Jones that have since been carried on by Black health workers, activists and their organizations. Medical racism has no place in a country where Black Americans, like those who worked and suffered during the 1793 yellow fever epidemic, have contributed so much to our society. It is an outdated racial science that not only has made the United States the most dangerous developed nation for Black pregnant people to give birth, but also has made a respiratory disease into a racialized disease.

Deirdre Cooper Owens is an educator, administrator and author of the award-winning “Medical Bondage: Race, Gender and the Origins of American Gynecology.”