The research is pretty clear that oppressive economic and social conditions are bad for one’s mental and physical health. And there is also research showing that protesting is good for one’s mental and physical health. As Dr. Bandy X. Lee, a psychiatrist at Yale University explains:

Can protesting and other forms of activism help people break out of those negative thought cycles? Yes, because protesting alone is therapeutic. It is acting on hope and it is also, in the case of oppression, therapeutic.

Now we have a study that finds that protesting actually saves lives. More specifically, that Black Lives Matter Protests reduce police killings. As Travis Campbell, the author of the study, concludes,

census places with Black Lives Matter protests experience a 15 percent to 20 percent decrease in police homicides over [the period 2014-2019], around 300 fewer deaths. The gap in lethal use-of-force between places with and without protests widens over these subsequent years and is most prominent when protests are large or frequent.

Black Lives Matter movement and protests

Campbell dates the rise of the Black Lives Matter movement to the outrage triggered by the acquittal of George Zimmerman for the 2013 killing of Trayvon Martin. Alicia Garza, an Oakland, California-based activist, posted a Facebook message saying “black people. I love you. I love us. Our lives matter.” Patrisse Cullors, another Oakland activist, began sharing the message along with the twitter tag #blacklivesmatters. And,

with the help of activist Opal Tometi, Black Lives Matter (BLM) was born.

Campbell dates the start of the Black Lives Matter protest movement to the explosion of protests in response to the 2014 police killings of Eric Garner in New York City and Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri. The protests continued, as did the police killings, among the most well-known victims being Tamir Rice, Walter Scott, Sandra Bland, Alton Sterling, Freddie Gray, Laquan McDonald, Philando Castile, Stephon Clark, Breonna Taylor, and George Floyd.

The study—killings and protests

Campbell sought to determine whether these BLM protests, motivated by police killings, actually helped to reduce them. An important question but one not easy to answer. His first challenge was to determine the actual number of police killings.

Unfortunately, there is no reliable federal database of police killings. There are, however, a number of nonprofit and media organizations that do maintain a public record. The most important are KilledByPolice.net, The Homicide Record by the Los Angeles Times, Mapping Police Violence (MPV), the Washington Post, the Counted by the Guardian, and Fatal Encounters Dot Org (FE).

Campbell uses the Fatal Encounters Dot Org database–which relies on the work of paid researchers, public records requests, and crowdsourcing for its information–for his study. Its dataset is updated regularly and begins in 2000. According to Campbell, the MPV database has the most complete information on victims, including their race and the circumstances surrounding their death, because it also makes use of social media sites, criminal records databases, and police reports. However, Campbell doesn’t use it. Its records only date back to 2013, which makes it impossible to determine pre-protest trends in police homicides in locations with BLM protests.

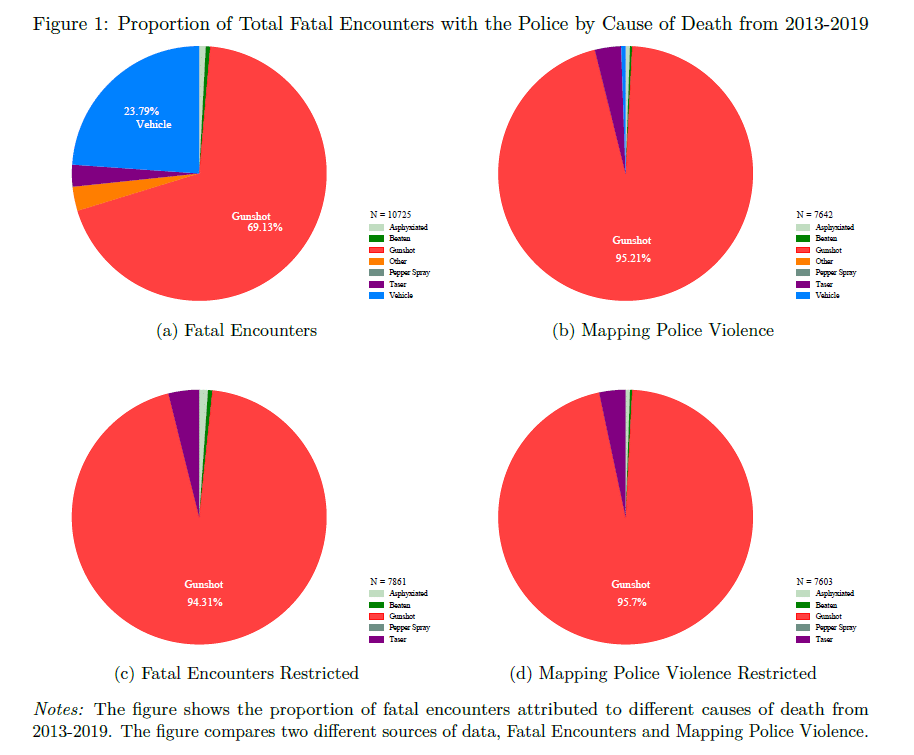

As for what constitutes a police homicide, FE uses a broad definition: all lethal interactions with police, whether on- or off-duty, including suicides. The MPV database only includes cases where “a person dies as a result of being shot, beaten, restrained, intentionally hit by a police vehicle, pepper-sprayed, tasered, or otherwise harmed by police officer whether on-duty or off-duty.” Campbell uses a more restrictive measure for his study, one that only includes police homicides due to asphyxiation, bludgeoning, a gunshot, pepper spray, or a taser that are not suicides.

As we can see from Figures 1 (c) and (d) below, which correspond to Campbell’s more restrictive measure, both FE and MPV include roughly the same number of total deaths with a correspondingly high share caused by gunshot. This similarity encourages confidence in the reliability of the FE database.

The second challenge is to determine the number of BLM protests. Campbell draws his data from a 2018 published study that covers protests over the years 2014-2015 and a public data base maintained by Alisa Robinson for the following years. To maintain a focus on street demonstrations Campbell does not include in his data “online demonstrations, protests by professional athletes, protests against presidential candidates, or protests against conservative talks at universities.”

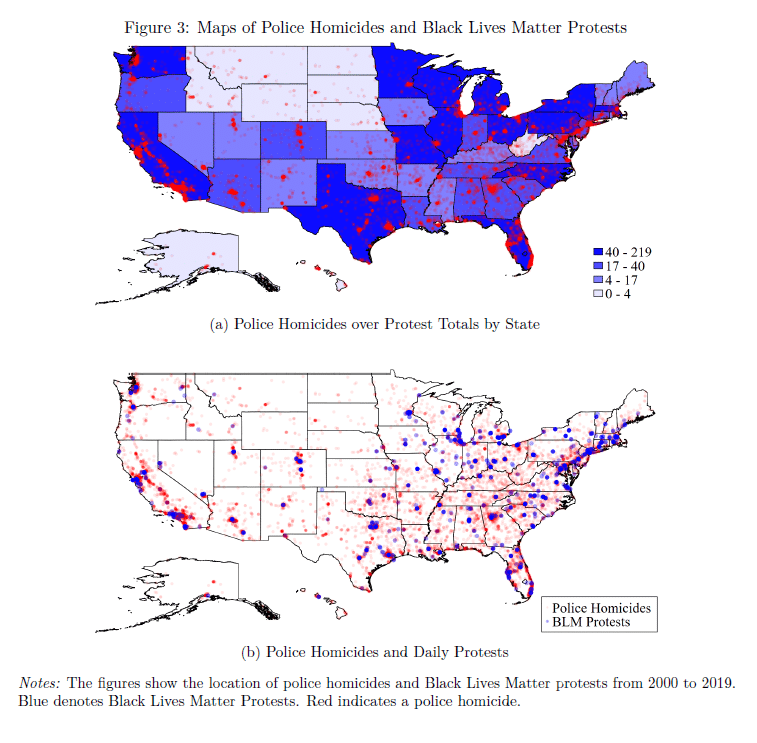

The following figure shows the location of the killings and protests used in the study.

The methodology

Campbell’s study includes every census place with a population of at least 20,000 people. Using a stacked difference-in-difference design, he tested whether Black Lives Matter protests had an effect on police killings in the locations where protests occurred. In broad brush, the design uses the locations where no Black Lives Matter protests occurred to develop a baseline trend, adjusted for relevant economic and social determinants (highlighted below), of police killings. Then, the adjusted baseline is applied to locations where Black Lives Matter protests have occurred to determine whether the protests had an independent effect on the number of police killings.

In recognition of the great differences between census areas, the adjusted baseline trend is calculated taking a number of different variables into account. These include: poverty rates, labor force participation rates, unemployment rates, full-time employment rates, black poverty rates; and educational attainment measures; rates and types of crime; and the number, renumeration, and training of police officers as well as officer demographics, unionization, use-of-force reporting, use of cameras, and community policing initiatives.

The results

The results are striking. As Campbell explains:

Following BLM protests, lethal use-of-force fell by 16.8 percent on average. If the model is correct, then BLM protests are responsible for approximately 300 fewer people being killed by the police from 2014 through 2019. The payoff for protesting is substantial; every 5 of the 1,654 protests in the sample correspond with approximately one less person killed by the police over the following years. The police killed one less person for every four thousand participants.

When Campbell normalized the homicides by population and gave added weight to larger census areas under the assumption that news reports of police killings and protests were likely more accurate there, the decline in police homicides grew to 19.8 percent.

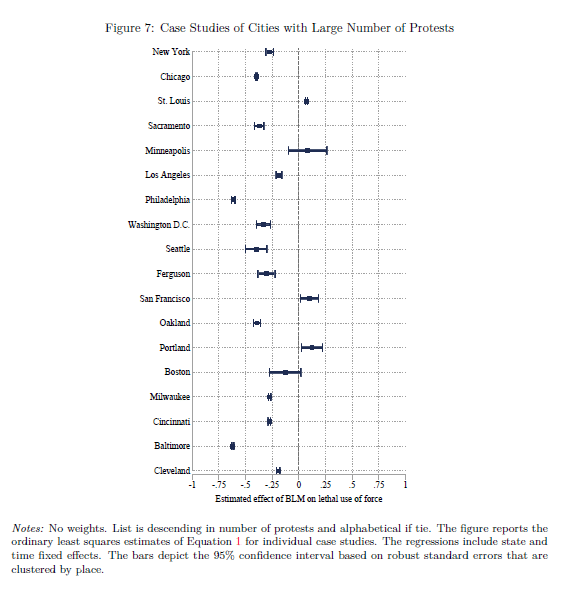

Campbell tested his conclusion by looking separately at the cities with the greatest number of protests. The figure below shows census places with the most protests in descending order, many of which were home to high profile police killings. As we can see, almost all experienced a statistically significant decline in police killings following protests. The exceptions were St. Louis, Minneapolis, San Francisco, and Portland.

As to possible explanations for the decline in police killings, Campbell found that the demonstrations appeared to force changes in local policing. For example, they increased police use of body-worn cameras, the number of police officers assigned to regular geographic patrols, and the adoption of a variety of community policing initiatives.

A Scientific American review of the study quotes Aldon Morris, the Leon Forrest Professor of Sociology and African American Studies at Northwestern University and president of the American Sociological Association a sociologist at Northwestern University:

The question becomes, ‘Are Black Lives Matter protests having any real effect in terms of generating change?’ The data show very clearly that where you had Black Lives Matter protests, killing of people by the police decreased. It’s inescapable from this study that protest matters—that it can generate change.

Hopefully that recognition—that BLM protests are saving lives—will encourage ever greater support for, and participation, in the movement, thereby helping to achieve the transformational changes in policing needed to protect the rights of communities of color to live safely and well.