Dear friends,

Greetings from the desk of the Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research.

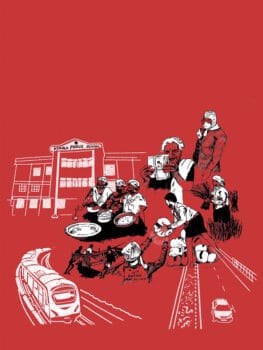

Indian farmers and agricultural workers have crossed the hundred-day mark of their protest against the government of Prime Minister Narendra Modi. They will not withdraw until the government repeals laws that deliver the advantages of agriculture to large corporate houses. This, the farmers and agricultural workers say, is an existential struggle. Surrender is equivalent to death: even before these laws were passed, more than 315,000 Indian farmers had committed suicide since 1995 because of the debt burden placed on them.

Over the next one and a half months, assembly elections will take place in four Indian states (Assam, Kerala, Tamil Nadu, and West Bengal) and in one union territory (Puducherry). There are 225 million people who live in these four states, which would, if measured by itself, make this area the fifth largest country in the world after Indonesia. Prime Minister Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) is not a serious contender in any of these states.

In Kerala (population 35 million), the Left Democratic Front has been in the government for the past five years, during which it has confronted a number of serious crises: the aftereffects of Cyclone Ockhi in 2017, the Nipah virus outbreak of 2018, the floods of 2018 and 2019, and then the COVID-19 pandemic. As a result, Kerala’s health minister, K.K. Shailaja, has earned the nickname the ‘Coronavirus Slayer’ because of the state’s rapid and comprehensive approach to breaking the chain of infection. All polls indicate that the Left will return to the government, breaking an anti-incumbency trend in the state since 1980.

To better understand the great gains made by the Left Democratic Front government over the past five years, I spoke to Kerala’s Finance Minister T. M. Thomas Isaac, a Central Committee member of the Communist Party of India (Marxist). Isaac begins by telling me that the switch back and forth between the Left Front and the Right Front, as he called it, has ‘cost Kerala a lot of social advancement’. If the Left wins again, he says, it will ‘be in power continuously for ten years. That is a sufficiently long period to leave a very substantial imprint upon Kerala’s development process’.

The general orientation of the Left’s approach toward Kerala’s development, Isaac said, has been ‘a kind of hop, step, and jump’:

The hop, the first stage, is redistributive politics. Kerala has been very noted for that. Our trade union movement has succeeded in having significant redistribution of income. Kerala has the highest wage rates in the country. Our peasant movement has been able to redistribute landed assets through a very successful land reform programme. Powerful social movements which pre-date even the Left movement in Kerala, [and] whose tradition the Left has carried forward, have pressurised successive governments which have been in power in Kerala to provide education, healthcare, [and for the] basic needs of everyone. Therefore, in Kerala, an ordinary person enjoys a quality of life which is much superior to the rest of India.

But there is a problem with this process. Because we have to spend so much on the social sector, there won’t be sufficient money [or] resources for building infrastructure. So [after] a programme of social development spread over more than half a century, there’s a serious infrastructure deficit in Kerala.

Our present government has been very remarkable in meeting the crises, ensuring that there is no social breakdown, ensuring that nobody in Kerala would go hungry, and [that] everybody will get treatment during COVID times and so on. But we did something more remarkable.

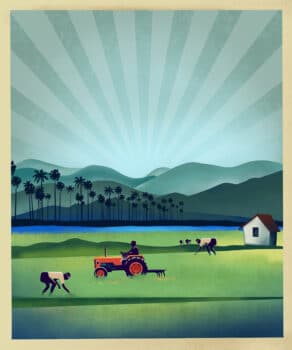

What the government did was to build the state’s infrastructure and begin to pivot to another economic foundation. The amount needed to upgrade the infrastructure is staggering, about Rs. 60,000 crores (or $11 billion). How does a Left government raise the funds to finance this kind of infrastructural development? Kerala, as a state within India, cannot borrow beyond a certain limit, so the Left government set up instruments such as the Kerala Infrastructure Investment Fund Board (KIIFB). Through the Board, the government was able to spend Rs. 10,000 crores (US$1.85 billion) and ‘has produced a remarkable change in the infrastructure’. After the hop (redistribution) and infrastructural development (step), comes the jump:

The jump is the programme that we have placed before the people. Now that infrastructure is there, [such as] transmission lines, assured electricity, industrial parks for investors to come and invest, we will have K-FON [Kerala-Fibre Optic Network], a super-highway of internet owned by the state, which is available to any service provider. [It ensures] equal treatment to everybody; nobody will have an [undue] advantage. And we are going to provide internet to everybody. It is the right of every individual. All the poor are going to get broadband connectivity for free.

All of this has provided a background for us to take the next big jump. That is, we now want to change the economic base of our economy. Our economic base is commercial crops, which are in serious crisis because of opening up [to ‘free trade’], or labour-intensive traditional industries, or very polluting chemical industries and so on. Therefore, we realise now, industries which are of our core competence would be knowledge industries, service industries, skill-based industries, and so on. Now how do you make this paradigm shift from your traditional economic base to the new [one]?

What will the new economic opportunities be for Kerala? First, because of the shift to the digital platform economy, Kerala will now develop its IT industry with the immense advantages of the state’s high literacy rates as well as 100% state-funded internet connectivity that will soon be available to the entire population. This, Isaac said, ‘is going to have a tremendous impact upon women’s employment’. Second, Kerala’s Left government will restructure higher education to promote innovation and deepen Kerala’s history of cooperative production (the example here is the Uralungal Labour Contract Cooperative Society, which recently rebuilt an old bridge in five months, seven months ahead of schedule).

Kerala aims to go beyond the paradigms of the Gujarat Model (high rates of growth for capitalist firms, but little social security and welfare for the people), the Uttar Pradesh Model (neither high growth nor social welfare), and the model that would provide high welfare but little industrial growth. The new Kerala project would go for high but managed growth and high welfare. ‘We want to create in Kerala [the basis for] individual dignity of life, security, and welfare’, Isaac says, which requires both industry and welfare. ‘We are not a socialist country’, he reminds me; ‘we are part of Indian capitalism. But in this part, within the limitations, we shall design a society which will inspire all progressive-thinking people in India. Yes, it is possible to build something different. That’s the idea of Kerala’.

A key element in the Kerala Model is the powerful social movements that grip the state. Amongst them is a mass front of the hundred-year-old communist movement and the All-India Democratic Women’s Association (AIDWA), which formed forty years ago in 1981 and which has a membership in excess of ten million women. One of the founders of AIDWA was Kanak Mukherjee (1921-2005). Kanakdi, as she was called, joined the freedom movement at the age of ten and never stopped fighting to emancipate our world from the chains of colonialism and capitalism. In 1938, at the age of seventeen, Kanakdi joined the Communist Party of India, using her immense talents to organise students and industrial workers. In 1942, as part of the anti-fascist struggle, Kanakdi helped found the Mahila Atma Raksha Samiti (‘Women’s Self Defence Committee’), which played a key role in helping those devastated by the Bengal Famine of 1943 – a famine created by imperialist policy that resulted in as many as three million deaths. These experiences deepened Kanakdi’s commitment to the communist struggle, to which she devoted the rest of her life.

A key element in the Kerala Model is the powerful social movements that grip the state. Amongst them is a mass front of the hundred-year-old communist movement and the All-India Democratic Women’s Association (AIDWA), which formed forty years ago in 1981 and which has a membership in excess of ten million women. One of the founders of AIDWA was Kanak Mukherjee (1921-2005). Kanakdi, as she was called, joined the freedom movement at the age of ten and never stopped fighting to emancipate our world from the chains of colonialism and capitalism. In 1938, at the age of seventeen, Kanakdi joined the Communist Party of India, using her immense talents to organise students and industrial workers. In 1942, as part of the anti-fascist struggle, Kanakdi helped found the Mahila Atma Raksha Samiti (‘Women’s Self Defence Committee’), which played a key role in helping those devastated by the Bengal Famine of 1943 – a famine created by imperialist policy that resulted in as many as three million deaths. These experiences deepened Kanakdi’s commitment to the communist struggle, to which she devoted the rest of her life.

To honour this pioneer communist, Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research dedicated our second feminisms study (Women of Struggle, Women in Struggle) to her life and work. Professor Elisabeth Armstrong, who was a key contributor to this study, recently published a book on AIDWA, which is now out as a paperback from LeftWord Books.

Today, organisations such as AIDWA continue to lift the confidence and power of working-class and peasant women, whose role has been considerable in Kerala and in the farmer’s revolt, as well as in struggles across the world. They speak out not only about their suffering but also about their aspirations, their great dreams of a socialist society–dreams that need to be built alongside other instruments such as the Left Democratic Front government in Kerala.

Warmly,

Vijay