A battle is slowly brewing in Washington DC over whether to raise corporate taxes to help finance new infrastructure investments. While higher corporate taxes cannot generate all the funds needed, the coming debate over whether to raise them gives us an opportunity to challenge the still strong popular identification of corporate profitability with the health of the economy and, by extension, worker wellbeing.

According to the media, President Biden’s advisers are hard at work on two major proposals with a combined $3 trillion price tag. The first aims to modernize the country’s physical infrastructure and is said to include funds for the construction of roads, bridges, rail lines, ports, electric vehicle charging stations, and affordable and energy efficient housing as well as rural broadband, improvements to the electric grid, and worker training programs. The second targets social infrastructure and would provide funds for free community college education, universal prekindergarten, and a national paid leave program.

To pay for these proposals, Biden has been talking up the need to raise corporate taxes, at least to offset some of the costs of modernizing the country’s physical infrastructure. Not surprisingly, Republican leaders in Congress have voiced their opposition to corporate tax increases. And corporate leaders have drawn their own line in the sand. As the New York Times reports:

Business groups have warned that corporate tax increases would scuttle their support for an infrastructure plan. “That’s the kind of thing that can just wreck the competitiveness in a country,” Aric Newhouse, the senior vice president for policy and government relations at the National Association of Manufacturers, said last month [February 2021].

Regardless of whether Biden decides to pursue his broad policy agenda, this appears to be a favorable moment for activists to take advantage of media coverage surrounding the proposals and their funding to contest these kinds of corporate claims and demonstrate the anti-working-class consequences of corporate profit-maximizing behavior.

What do corporations have to complain about?

What do corporations have to complain about?

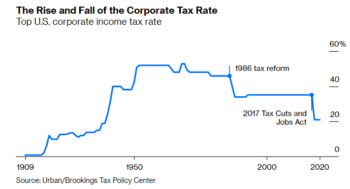

To hear corporate leaders talk, one would think that they have been subjected to decades of tax increases. In fact, quite the opposite is true. The figure below shows the movement in the top corporate tax rate. As we can see, it peaked in the early 1950s and has been falling ever since, with a big drop in 1986, and another in 2017, thanks to Congressionally approved tax changes.

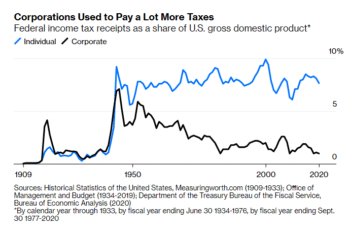

One consequence of this corporate friendly tax policy is, as the following figure shows, a steady decline in federal corporate tax payments as a share of GDP. These payments fell from 5.6 percent of GDP in 1953 to 1.5 percent in 1982, and a still lower 1.0 percent in 2020. By contrast there has been very little change in individual income tax payments as a share of GDP; they were 7.7 percent of GDP in 2020.

One consequence of this corporate friendly tax policy is, as the following figure shows, a steady decline in federal corporate tax payments as a share of GDP. These payments fell from 5.6 percent of GDP in 1953 to 1.5 percent in 1982, and a still lower 1.0 percent in 2020. By contrast there has been very little change in individual income tax payments as a share of GDP; they were 7.7 percent of GDP in 2020.

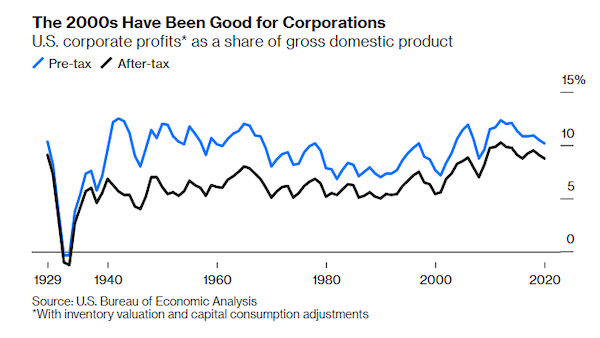

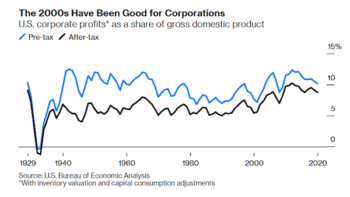

Congressional tax policy has certainly been good for the corporate bottom line. As the next figure illustrates, both pre-tax and after-tax corporate profits have risen as a share of GDP since the early 1980s. But the rise in after-tax profits has been the most dramatic, soaring from 5.2 percent of GDP in 1980 to 9.1 percent in 2019, before dipping slightly to 8.8 percent in 2020. To put recent after-tax profit gains in perspective, the 2020 after-tax profit share is greater than the profit share in every year from 1930 to 2005.

What do corporations do with their profits?

What do corporations do with their profits?

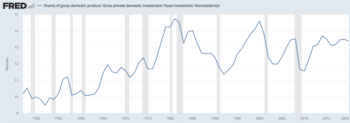

Corporations claim that higher taxes would hurt U.S. competitiveness, implying that they need their profits to invest and keep the economy strong. Yet, despite ever higher after-tax rates of profit, private investment in plant and equipment has been on the decline.

As the figure below shows, gross private domestic nonresidential fixed investment as a share of GDP has been trending down since the early 1980s. It fell from 14.8 percent in 1981 to 13.4 percent in 2020.

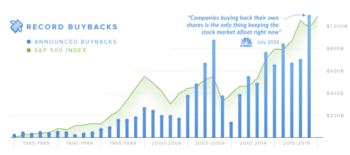

Rather than investing in new plant and equipment, corporations have been using their profits to fund an aggressive program of stock repurchases and dividend payouts. The figure below highlights the rise in corporate stock buybacks, which have helped drive up stock prices, enriching CEOs and other top wealth holders. In fact, between 2008 and 2017, companies spent some 53 percent of their profits on stock buybacks and another 30 percent on dividend payments.

Rather than investing in new plant and equipment, corporations have been using their profits to fund an aggressive program of stock repurchases and dividend payouts. The figure below highlights the rise in corporate stock buybacks, which have helped drive up stock prices, enriching CEOs and other top wealth holders. In fact, between 2008 and 2017, companies spent some 53 percent of their profits on stock buybacks and another 30 percent on dividend payments.

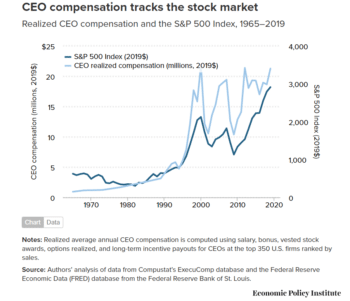

It should therefore come as no surprise that CEO compensation is also exploding, with CEO-to-worker compensation growing from 21-to-1 in 1965, to 61-to-1 in 1989, 293-to-1 in 2018, and 320-to-1 in 2019. As we see in the next figure, the growth in CEO compensation has actually been outpacing the rise in the S&P 500.

It should therefore come as no surprise that CEO compensation is also exploding, with CEO-to-worker compensation growing from 21-to-1 in 1965, to 61-to-1 in 1989, 293-to-1 in 2018, and 320-to-1 in 2019. As we see in the next figure, the growth in CEO compensation has actually been outpacing the rise in the S&P 500.

In sum, the system is not broken. It continues to work as it is supposed to work, generating large profits for leading corporations that then find ways to generously reward their top managers and stockholders. Unfortunately, investing in plant and equipment, creating decent jobs, or supporting public investment are all low on the corporate profit-maximizing agenda.

Thus, if we are going to rebuild and revitalize our economy in ways that meaningfully serve the public interest, working people will have to actively promote policies that will enable them to gain control over the wealth their labor produces. One example: new labor laws that strengthen the ability of workers to unionize and engage in collective and solidaristic actions. Another is the expansion of publicly funded and provided social programs, including for health care, housing, education, energy, and transportation.

Thus, if we are going to rebuild and revitalize our economy in ways that meaningfully serve the public interest, working people will have to actively promote policies that will enable them to gain control over the wealth their labor produces. One example: new labor laws that strengthen the ability of workers to unionize and engage in collective and solidaristic actions. Another is the expansion of publicly funded and provided social programs, including for health care, housing, education, energy, and transportation.

And then there are corporate taxes. Raising them is one of the easiest ways we have to claw back funds from the private sector to help finance some of the investment we need. Perhaps more importantly, the fight over corporate tax increases provides us with an important opportunity to make the case that the public interest is not well served by reliance on corporate profitability.