On 57th anniversary of military coup in Brazil, the National Security Archive Posts Declassified Documentation on Brazilian Regime’s Effort to Subvert Democracy and Support Dictatorship in Chile

New Book Reveals Brazilian Intervention to Undermine Allende, Bolster Pinochet

The Chilean ambassador to Brazil, Raúl Rettig, sent an alarming cable in March 1971 to his foreign ministry titled “Brazilian Army possibly conducting studies on guerrillas being introduced into Chile.” Multiple sources had informed the Embassy that the Brazilian military regime was evaluating how to instigate an insurrection to overthrow the Allende government. The military had established a “war room” with maps and models of the Andean mountain range along the Chilean border to plan infiltration operations, stated the cable, classified “strictly confidential.” According to Rettig’s report, “the Brazilian Army apparently sent a number of secret agents to Chile who would have entered the country as tourists, with the intention of gathering more background on possible regions where a guerilla movement might operate.” No date had yet been set, one informant said, to initiate this “armed movement.”

The revealing Rettig cable is one of hundreds of documents obtained from Brazilian, Chilean and U.S. archives by investigative reporter Roberto Simon for his new book, Brazil against Democracy: the Dictatorship, the Coup in Chile and the Cold War in South America. Published in Brazil last month, the book exposes the clandestine role Brazil’s military regime played in the September 11, 1973, coup that brought General Augusto Pinochet to power, as well as the Brazilian contribution to Chile’s apparatus of repression during his 17-year dictatorship.

“The book shows how the Brazilian military dictatorship actively worked to undermine Chile’s democracy during the Allende years and, after 1973, to help the Chilean junta consolidate its power,” Simon noted in an interview with the National Security Archive.

“The book shows how the Brazilian military dictatorship actively worked to undermine Chile’s democracy during the Allende years and, after 1973, to help the Chilean junta consolidate its power,” Simon noted in an interview with the National Security Archive.

Brazil provided direct support to, and a model for, the Pinochet dictatorship.

In addition to Brazil’s reported plan to foment an anti-Allende insurrection in Chile, the book contains numerous other historical revelations, among them:

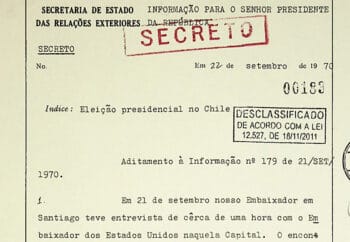

- Within days of Salvador Allende’s historic election on September 4, 1970, the U.S. ambassador to Chile, Edward Korry, met with Brazil’s ambassador in Santiago, Antonio Cândido da Câmara Canto, and shared details of initial U.S. efforts to block Allende’s inauguration. On White House orders, Korry said, the Embassy was passing hostile information about Allende to Chilean military commanders and threatening to cut off economic aid and credits if he assumed the presidency of Chile. Ambassador Câmara Canto’s report on the meeting was considered so important in Brazil that Foreign Minister Mario Gibson Barboza summarized it in a report to the President of the military regime, General Emílio Garrastazu Médici.

- The Brazilian military established back-channel communications with Chilean military officers who opposed Allende and even secretly arranged for some of them to come to Brazil for discussions about coup plotting.

- Brazilian agents established ties with the pro-terrorist Patria y Libertad organization in Chile. After a failed coup attempt in June 1973, Brazil provided protection and asylum for senior members of Patria y Libertad.

- Brazil obtained intelligence on early coup plotting, identifying military officials who were preparing to overthrow Allende. At one meeting held at the El Bosque airbase on August 2, 1973, Chilean officers evaluated the elements of the 1964 coup in Brazil to see what might be useful for their plans to assume power.

- In the days after the September 11, 1973, military golpe, Brazil’s foreign ministry aided the new Chilean junta’s diplomatic effort to present the coup in the most positive light. The book provides new details on Brazil’s effort to be the first country to officially recognize Chile’s new military regime. Brazilian officials also helped draft some of the initial speeches for Pinochet’s representatives at the United Nations to justify the bloody coup at the U.N. General Assembly. Brazil also poured considerable economic aid and financial credits into Chile following the coup, totaling over $1.2 billion in today’s dollars.

- Brazil sent a team of intelligence agents to Santiago to participate in the prisoner interrogations at the National Stadium, which became a mass detention, torture, and execution center after the coup. According to the book, the secret mission was led by Colonel Sebastião Ramos de Castro, from Brazil’s intelligence service, the Serviço Nacional de Informações, (SNI).

- Brazil trained dozens of officials and agents from the feared Chilean secret police force, DINA, among them agents who participated in international assassination missions including the car-bombing of former Ambassador Orlando Letelier and his colleague, Ronni Karpen Moffitt, in Washington D.C. Senior military officials also spent considerable time in Brazil, among them Humberto Gordon, who was stationed in Brasília as a “military attaché” in 1974 and rose to become head of Pinochet’s secret police agency, the Central Nacional de Informaciones (CNI).

- Drawing on U.S. intelligence records declassified in 2019, the book presents a more detailed description of Brazil’s role in the Southern Cone collaboration of secret police forces known as Operation Condor. Brazil, according to one CIA document, attempted to “control” Condor’s missions, resisting efforts by Chile, Uruguay, and Argentina to engage in targeted assassination operations outside the Southern Cone, and preferring to engage in a number of bilateral rendition operations to kidnap and disappear leftist opponents in the region. According to a 1977 State Department intelligence analysis, Brazil–along with its smaller allies, Paraguay and Bolivia–was “(acting) as a damper on Condor,” and Brazilian officials had stopped attending Condor meetings.

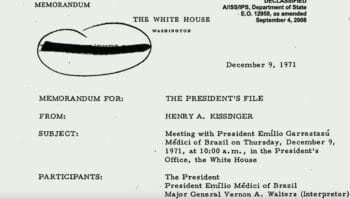

The book highlights a dramatic scene in December 1971 when the head of Brazil’s military regime, General Emílio Garrastazu Médici, came to Washington and met privately with President Richard Nixon at the White House. The two leaders candidly discussed efforts to depose Allende. Médici told Nixon that Allende would be overthrown “for very much the same reasons that Goulart had been overthrown in Brazil,” and “made it clear that Brazil was working towards this end.”

Nixon responded “that it was very important that Brazil and the United States work closely in this field” and offered “discreet aid” and money for Brazilian operations against the Allende government. Nixon made clear that Brazil could help the U.S. defeat Allende and other leftist governments and movements throughout Latin America and said he “hoped we could cooperate closely, as there were many things that Brazil as a South American country could do that the U.S. could not.”

The now famous Nixon-Médici Oval Office meeting was recorded in a Top Secret White House memorandum of conversation that the National Security Archive first obtained and publicized in 2009; the Archive also posted CIA intelligence summaries of reaction to the meeting by some Brazilian military officers, including one who believed that “the United States obviously wants Brazil to ‘do the dirty work’” in South America.

The now famous Nixon-Médici Oval Office meeting was recorded in a Top Secret White House memorandum of conversation that the National Security Archive first obtained and publicized in 2009; the Archive also posted CIA intelligence summaries of reaction to the meeting by some Brazilian military officers, including one who believed that “the United States obviously wants Brazil to ‘do the dirty work’” in South America.

But, the abundance of documentary evidence that Roberto Simon has meticulously gathered for O Brasil Contra A Democracia reveals that Brazil did its own ‘dirty work’ in Chile—as well as in Uruguay, Bolivia, and other parts of the Southern Cone. Although the military regime may have coordinated and collaborated with the Nixon administration, Brazil’s military dictatorship acted for its own geo-political preservation, rather than at the behest of Washington.

“The image of Brazil’s military regime as ‘Washington’s puppet,’ fully aligned with the regional superpower, is a myth that relegates Brazil to a mere subsidiary role in the region,” Simon asserts in his introduction.

The book demonstrates that the opposite was true: the Brazilian dictatorship had its own motivations–strategic, ideological, economic and more–to intervene in Chile.

Indeed, the book represents a watershed publication for the historiography of the overthrow of democracy and advent of dictatorship in Chile—a historiography which has, until now, focused almost exclusively on the role of U.S. covert intervention in the September 11, 1973 military coup. “This book is a game changer for the historical narrative on imperial intervention in Chile,” according to Peter Kornbluh, who directs the Chile and Brazil documentation projects at the Archive.

It provides a far fuller understanding of the history of foreign violations of Chile’s sovereignty, and suggests there is more to be learned.