Ramsey Clark, former U.S. Attorney General and renowned international human-rights attorney who stood against U.S. military aggression worldwide, died peacefully April 9 at his home in New York City, surrounded by close family. He was 93 years old.

As a pre-teen growing up in Albuquerque, I certainly knew his name and that he was attorney general. I could not imagine then that we would become friends, that I would have the honor of working with him and learning what a great humanitarian Ramsey Clark was.

As Assistant and later U.S. Attorney General, Ramsey Clark helped draft the two historic U.S. Civil Rights Acts of 1964 and 1968, the Voting Rights Act of 1965, and was key enforcer of federal desegregation orders. Personally accompanying Martin Luther King Jr. and James Meredith in the face of racist terror from Alabama to Mississippi, Ramsey was a fervent opponent of racism. In the Justice Department, he frequently confronted repressive policies within the government itself, from Congress to the FBI and J. Edgar Hoover.

Once out of government, Ramsey took on U.S. foreign policy directly, traveling to dozens of countries to meet the people who were victims of war and sanctions. Whether it was defying U.S. bombs in North Vietnam in 1972 or counting the bodies in Panama morgues and the bombed-out neighborhood of El Chorrillo to tally the true number of casualties in the 1989 U.S. invasion, Ramsey risked his life countless times to bring back the truth of U.S. aggression.

He famously traveled 2,000 miles through Iraq in the midst of intense bombing during the 1991 U.S. Gulf War to bring back the only uncensored film of the war. And for 12 years until the 2003 U.S. war and occupation, Ramsey led an international campaign against the U.S. total blockade of Iraq–sanctions more deadly than a bombing war.

On every continent, Ramsey Clark defended peoples and countries against injustice and poverty. He saw U.S. war and sanctions as being the greatest threat to humanity.

He described the U.S. government and system as a “plutocracy” and denounced the growing injustice and repression in the United States. In the 1960s, Ramsey famously called for “the abolition of the U.S. prison system as we know it,” years before it became a rallying slogan in today’s movement. He was strongly opposed to the death penalty.

The hallmark of Ramsey Clark’s advocacy was his unshakeable belief that human rights meant the right to peace, equality and social and economic justice. He did more than advocate, he acted on his beliefs.

Born William Ramsey Clark on Dec. 18, 1927, his father Tom C. Clark was U.S. Attorney General from 1945 to 1949 and a Supreme Court justice from 1949 to 1967. His mother Mary was primary caregiver to Ramsey, Tom Jr. and sister Mimi. His brother died at six years from pneumonia when Ramsey was four. Ramsey spent his childhood in Dallas until his father took a position in the Justice Department in Washington, D.C., in 1937. Although he tried to join the Marines at age 13 during World War II, he was finally accepted at 17 in the last year of the conflict.

Starting out as a private attorney, he soon began his career in the Justice Department, which lasted from 1961 to 1969.

A firm advocate of civil rights and opponent of racism

In 1961, Ramsey Clark became Assistant Attorney General in the Kennedy administration for the Lands division of the Justice Department. Yet his primary work was in civil rights defense against Jim Crow apartheid in the South and violence by racist mobs and governments. He was the principal on-the-ground enforcer of the 1954 U.S. Supreme Court ruling, Brown v. Board of Education, against the states of Georgia, South Carolina and Alabama. They were stalling or refusing to desegregate the public schools eight years after the court order. Ramsey worked there directly in 1962 and 1963 to oversee the ruling’s implementation.

In 1965, President Lyndon Johnson appointed Ramsey as Deputy Attorney General. When Black people set out to march from Selma to Montgomery, Ala., for the right to vote, they were brutally assaulted by state troopers on March 7 and March 9 and faced KKK and White Citizens Council terror. As thousands of people gathered for a third peaceful action that began on March 21, Ramsey was sent to try to ensure the protesters’ protection, under the federally deputized presence of the Alabama National Guard.

In June 1964, three civil rights activists–20-year-old Black Mississippian James Chaney, and white youths Andrew Goodman and Michael Schwerner–were arrested in Philadelphia, Miss., by deputy sheriff Cecil Price, a member of the White Knights of the KKK. He released them after summoning more Klan members, who together tortured and murdered the three young men. Their bodies were found in August. The shocking episode was met with national revulsion and was one of the catalysts for the civil rights acts.

Ramsey Clark went to see Chaney’s family at their home to tell them the bodies of James, Andrew and Michael were found. Young Ben was only 12 years old. When he heard his brother was dead, he told Ramsey, “I guess I’d better become president to change all this.” Ben and his family moved to New York City to escape death threats. As a Black Liberation activist only 17 years old, Ben Chaney was railroaded into prison with three life terms in Florida, despite not being involved in the crime he was convicted of. Ramsey never forgot Ben and the trauma he suffered losing his brother. He successfully petitioned the Florida parole board for Ben’s release, and he was freed after 13 years. He subsequently worked as a clerk in Ramsey’s law office for years.

Ramsey Clark was a man of principle who held to his views that the greater danger was not anti-war or anti-racist activists, but the injustices they were protesting. He famously refused to permit the wiretapping of Black liberation leader Stokely Carmichael (later Kwame Toure) despite J. Edgar Hoover’s and Vice President Hubert Humphrey’s repeated insistence. Ramsey refused demands from politicians to prosecute Stokely Carmichael for “aiding and abetting draft evasion during the Vietnam war.”

After Ramsey was replaced as Attorney General with Richard Nixon’s election, he wrote a seminal book, “Crime in America: Observations on Its Nature, Causes, Prevention and Control,” focusing on the real cause of crime, poverty and racial inequality. He openly criticized the arch-racist FBI director in the book: “Mr. Hoover repeatedly requested me to authorize FBI wiretaps on Dr. King when I was A.G. His last of these requests, none of which was granted, came two days before the murder of Dr. King.”

Mike Wallace, prominent CBS newsman, in a national TV program about J. Edgar Hoover’s blackmail tactics to intimidate his opponents, remarked, “There was only one man not afraid to stand up to Hoover: Ramsey Clark.”

A committed internationalist

With his return to private practice in 1969, Ramsey became a leading defender of the victims of U.S. foreign policy. He would travel to over 120 countries to express solidarity with oppressed peoples, from Palestine to India to South Africa. He was an abiding opponent of all U.S. bombings, sanctions and occupations, and sought to rally the people of the United States and worldwide.

The war crimes he exposed by his courageous first-hand reporting made him often the sole source of truth to counter the lies of the massive U.S. war propaganda that preceded the bombs. Both the liberal and neoconservative establishment–frequently in lockstep backing a new U.S. military adventure–often made him the subject of derisive smear campaigns by the “Pentagon stenographers’ pool.”

But Ramsey Clark was never deterred nor discouraged, never fearful of media and government critics, regardless of political pressures. This was true when he visited North Vietnam in 1972.

Invited by the International Commission for Inquiries into United States War Crimes in Indochina to join an investigative delegation to Vietnam in 1972, Ramsey accepted. He visited and interviewed U.S. soldiers who were prisoners of war, and toured the dikes and sluice gates in the North that were being heavily bombed. U.S. B-52s were dropping bombs and killing civilians, hitting their water source to destroy the people’s means of survival in a primarily rural population.

When he returned to San Francisco and held a press conference on August 14, Ramsey Clark stated the prisoners were treated well. “I’ve seen a lot of prisons in my life,” he said, according to The New York Times. “These 10 men were unquestionably humanely treated, well treated. Their individual rooms were better and bigger than the rooms in essentially every prison I have ever visited anywhere.”

When challenged on whether he thought the U.S. bombing of civilian targets was deliberate, he responded, “We are bombing the hell out of that poor land. We are hitting hospitals. I can’t tell you whether it’s deliberate. But to the people who are getting hit, it doesn’t make much difference, does it?” Over 3 million Vietnamese people and 57,000 U.S. soldiers died over the course of the war.

Opposing deadly sanctions

When the war was over with Vietnam’s unification and total victory in 1975, Clark did what no other leading voice against the war did. To him, the war against Vietnam was not over because U.S. economic sanctions were deliberately punishing the country and denying its ability to recover from the devastation, causing the deaths of thousands more. The sanctions were finally ended in 1994, 19 years later.

Within days of Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait in August 1990, the United States led the permanent members of the UN Security Council to impose “sanctions.” Many in the U.S. peace movement put forward the slogan, “Sanctions, Not War,” acquiescing to the first stage of inevitable war. Ramsey and the anti-imperialist coalition he helped lead denounced the sanctions as a means of war, knowing that a U.S.-enforced naval blockade was calculated to starve the people first, and then bomb if hunger didn’t work.

The National Coalition to Stop U.S. Intervention in the Middle East was headed by Ramsey and anti-war organizers. Within a few weeks of the bombing beginning Jan. 16, 1991, Ramsey Clark led a team of a translator, a driver and filmmaker Jon Alpert. With no electricity or gasoline in the country and bombs dropping day and night, he traveled 2,000 miles the whole length of Iraq.

Ramsey was determined to show that the Pentagon’s myth of “collateral damage,” of supposed minimal loss of life, was an absolute lie meant to soften anti-war sentiment in the population. Jon Alpert’s film, “Nowhere to Hide,” was the only uncensored footage of the 43-day bombing.

When Ramsey came to San Francisco soon after his return from Iraq in early February 1991, he spoke to a packed audience of 1,200 people at Third Baptist Church in the heart of the Black community. “Nowhere To Hide” was a shocking revelation as the video showed Ramsey touring bombed-out villages and hospitals in the film. The only powdered-milk plant for baby formula was obliterated by U.S. bombs. Iraq’s whole infrastructure–water treatment and sewage plants, the electrical grid, poultry and livestock–everything was gone within 24 hours of the carpet bombing.

Until that film was shown in the United States and worldwide, every major media outlet repeated the Pentagon’s lies of “collateral damage” as if civilian casualties were an unfortunate accident.

This is the fabricated lie the public is told of every U.S. war and blockade, as millions of people face severe hardship and famine in countries blockaded by Washington. I often told people in these last few years, if Ramsey were physically able, he would be with the people of Yemen, using his international fame to shed light on the genocide committed by Saudi Arabia, fully backed by U.S. imperialism.

Ramsey’s book about the Gulf War, “The Fire This Time,” details the destruction of Iraq’s civilian infrastructure, the deaths of 250,000 people from the bombs.

When the U.S. troops came home, the following 12 years of total U.S. blockade–the euphemistic “sanctions” that some liberals applauded–continued. The blockade killed more than 1.5 million Iraqi people, until the 2003 invasion and occupation.

Ramsey submitted his yearly findings on the effects of those murderous sanctions to the United Nations. He traveled again and again to Iraq. I had the honor of accompanying him and a delegation of 84 other organizers, lawyers, doctors and trade unionists in May 1998. We walked through the horror of hospital after hospital where no medicine or working equipment existed because U.S./UN sanctions prohibited even aspirin from coming in. The situation was horrific–babies dying from treatable infections, the elderly and youth dying from exposure to depleted-uranium of U.S. bombs.

My film, “Genocide by Sanctions: The Case of Iraq” documenting Ramsey’s 1997 trip exposed the theme of “sanctions, not war” for what it really is: a lie.

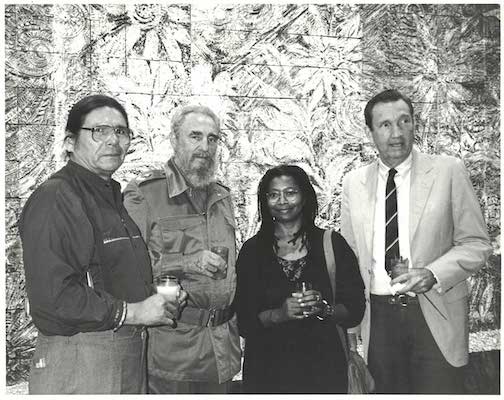

Ramsey Clark receives Cuba’s Solidarity Medal. With him, Mothers of the Cuban Five, Mirta Rodríguez, Irma Sehwerert, Magali Llort. Credit: Gloria La Riva

Ramsey was a fervent supporter of the Palestinian people’s rights and he was a beloved figure throughout the Arab world. He was the lawyer for the Palestine Liberation Organization in the United States and in many international legal arenas when almost no one else in the United States was willing to stand with the just cause of the Palestinian and Arab people. Ramsey carried out this solidarity with the Palestinian and Arab people during the decades when the Israeli government and right wing’s ludicrous assertion that doing so was anti-semitic was even more dominant. He was one of the most prominent critics in the west of the U.S. puppet regime of the Shah in Iran.

Cuba was of enormous importance to Ramsey Clark and he traveled to the island many times. He lauded Cuba’s social accomplishments, and gave his active support to the Pastors for Peace “Friendshipment Caravan” as it crossed into Mexico on its way to Cuba in 1993. He called for six-year-old Elián González’s immediate return home. He said of the Cuban Five’s wrongful imprisonment in the United States that if he were attorney general he would have thrown out their charges. For his years of support for Cuba and his opposition to the U.S. genocidal blockade, he was awarded the Solidarity Medal in 2012, accompanied by the Cuban Five’s mothers.

Ramsey made multiple trips to the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea or North Korea as well as to South Korea. In 2001 he was the keynote speaker and principal jurist at the International Tribunal on U.S. War Crimes in the Korean War. The Tribunal presented expert testimony and drew participation from people all over the world. Ramsey’s last trip to North Korea was in July 2013 to mark the 60th anniversary of the Armistice Agreement that ended military hostilities in Korea in 1953. While in Pyongyang and in subsequent trips to Seoul and Tokyo, Ramsey spoke eloquently about the need to end sanctions on North Korea and demanded that the United States sign a peace treaty with North Korea to end the Korean War once and for all.

There was not a struggle or cause for social justice that Ramsey did not support.

Anyone who had the opportunity to spend a few hours with him would get a memorable history lesson from his experiences. I once drove him in California to a university engagement three hours up and back. Ramsey told me the whole story of Ruchell Magee’s life, whom he tried to free in appeals, and the absolute cruelty he has been subjected to by the “justice” system.

He was a firm believer in Native people’s sovereign rights and was instrumental in settling key land claims that had not been done in 50 years.

On Jan. 1, 1994, when the Zapatista rebellion rose up in Chiapas, Mexico, Ramsey, true to form, knew he had to be there to investigate and show his support. I was fortunate to be in that small team with Brian Becker and others within a week of the uprising. The heroic action of Indigenous Mayan people was prompted by the NAFTA free trade agreement, signed by presidents Bill Clinton and Carlos Salinas. The Zapatistas knew NAFTA would destroy their livelihoods by flooding U.S. products like corn into Mexico.

The fear of the Mexican army’s repression was palpable. The Mexican and international press, and liberals sympathetic to the plight of the Indigenous people, nonetheless were reluctant to give credence to the armed struggle. At the conclusion of our visit, Ramsey declared to hundreds of journalists at a hotel press conference in San Cristobal de las Casas that their armed struggle–“the shot heard around the world” as he called it–was wholly justified.

Ramsey was an appeals attorney for Native political prisoner Leonard Peltier, who today is still in U.S. federal prison 45 years after being railroaded by the FBI. In a mass indoor rally for Leonard in San Francisco of almost 1,000 people on Nov. 16, 1997, Ramsey told a cheering crowd, “Everyone knows, and most of all the prosecutors and the FBI, that Leonard Peltier is innocent of the crime for which he has been convicted. … It is essential that we free Leonard Peltier and in doing so, recognize Indigenous and Native people as first, first, first among equals. Until Leonard is free, we are all at risk. He represents whether the American people have the will to stand up finally to powerful economic interests that control the media and the military-industrial complex, that are ravaging poor people across the planet. Whether we have the will to stand up and stop the American government in its tracks before it is too late.”

Early the next morning Ramsey flew from San Francisco to Yugoslavia to show support for that beleaguered country. Yugoslavia was at that point the only socialist government in Europe that had not been toppled by the capitalist counterrevolutions that swept the region from 1988 to 1991. But the United States was determined to destroy the government and two years later it did. In March 1999, the U.S./NATO 73-day bombing campaign began under the pretext of defending a Muslim minority people in the Serbian province of Kosovo.

U.S. imperialism’s demonization of Yugoslavia’s leader Milosevic in the corporate media effectively neutralized many of the traditional U.S. peace organizations. But thousands of people from the anti-imperialist wing of the U.S. anti-war movement took to the streets. Soon all of Yugoslavia’s people became NATO targets. NATO, under the leadership of the Pentagon and the Clinton administration, dropped 28,000 bombs and missiles on this small country in central Europe. Many liberals, even some well-known progressive activists, lamented Ramsey’s active defense of Yugoslavia. They only saw what CNN, NBC and The New York Times wanted them to see–Milosevic as the only occupant of Yugoslavia.

But Ramsey, guided by his moral compass, saw through the Pentagon propaganda machine. As soon as the bombs began dropping on March 24, 1999, I had the privilege once again of flying with him, this time to Hungary. We were driven to Belgrade, Yugoslavia, on the fifth day of the war to document the devastating effects on the civilian population.

It became my documentary, “NATO Targets Yugoslavia.” Literally every day of the war, CNN would report that the bombing the day before was “the heaviest bombing yet by NATO forces.” Ramsey flew there on the 55th day of the war. I accompanied him again.

One especially dramatic episode with Ramsey occurred when the counterrevolution took place in Yugoslavia in late June 2001. Milosevic was overthrown in a CIA-engineered “color revolution.” The new coup government quickly began arresting Yugoslav socialists and other patriots who led the resistance to the 1999 NATO bombing.

Ramsey decided he wanted to fly there right away. By then the Yugoslav embassy in Washington, D.C., had changed hands to the right wing and refused him a visa. That did not stop Ramsey. He called me in San Francisco and said, “Take the next plane to JFK. I can meet you at the airport.” When I got there we raced through the terminal as fast as we could. The gate to the plane was closing, ready for takeoff.

When we finally arrived in Belgrade, we stood in the immigration line and as we approached the window, the staff slammed it shut. Officials came up to us and said, “You have to leave the country, you can’t stay. Get back on the plane now.” Ramsey said, “I’m Ramsey Clark and … ” to which they replied, “We know who you are, get on the plane.” We said, “No, we need to make a phone call to our hosts waiting outside.” Our friends in the Socialist Party were waiting to pick us up.

That plane took off. Another plane coasted up on the tarmac returning to Paris. Again, the officials insisted, “Get on this plane, now!” We refused. Then that one took off too. How long we could continue we did not know.

Then two police, a woman and a man, came up to us. The young woman said, “Please give me your passports.” The man said to me, “Follow me.” And he led me to the airport terminal, took me to a kiosk and said, “You can make your phone call.” When I returned to Ramsey, the policewoman handed us our passports, complete with visas. She said emotionally to Ramsey: “We will never forget what you did for our people, supporting us during the war. My brother was in the army and he was injured fighting.”

She paused and said brightly, “I’ll see you tonight at the rally!”

When we arrived at the mass rally protesting Milosevic’s illegal arrest and kidnapping to The Hague on trumped-up charges by the imperialist court, the crowds cheered Ramsey. They saw in him a true friend. It was quite an adventure, like one that could only happen in a movie.

A humanitarian loved worldwide

In January 2004, Ramsey Clark and I were at the World Social Forum in Mumbai, India. I was there for the freedom struggle of the Cuban Five. Of course, Ramsey also spoke on their behalf as well on other themes in our days there. At the end of one of his presentations, in walked Winnie Mandela. I was stunned at the presence of this revolutionary woman leader. She said out loud as she walked up to embrace Ramsey, “When I heard Ramsey Clark was here, I had to come see him.” They had a warm and happy exchange.

Later that day, he remarked to me, “She suffered as much as Nelson Mandela if you think about it. She suffered imprisonment, police abuse, banishment, isolation from her children and husband.” He told me he went to South Africa to visit her one time. Banished, she could not even open the door to let him in and she could not leave her house. And just because Ramsey put his hand up to the screen door as a “handshake,” to touch her hand through the screen, she was forced to a more isolated banishment.

Ramsey was known and loved worldwide by millions of people whom he defended.

I have witnessed too many of those expressions of admiration and love for Ramsey’s internationalist missions to relate them here. Ramsey Clark’s legal and political life have filled books and library archives. So much more could be said.

A special history of his life is told in the award-winning documentary produced by renowned filmmaker Joe Stillman, “Citizen Clark: A Life of Principle.” Joe says, “When I learned the details of his life, I knew I had to tell his story. I had a choice, either buy myself a house or put my money into a film about Ramsey. I’m glad I documented his life. I would do it again in a heartbeat.”

In Yugoslavia on Ramsey’s first wartime trip in March 1999, I was filming him as he spoke to a packed audience of academics, jurists and attorneys. He mentioned that it was his 50th anniversary of marriage to his wife Georgia, and he spoke with great love and affection about her. He said she supported his absence during their anniversary as necessary to defend those who needed a defense. Georgia shared his belief in social justice and she worked for years in his law offices, while they raised two children, Tom and Ronda. They also traveled frequently as a family.

Sadly, Georgia died in 2010. Tom, an environmental attorney in the Justice Department, died of cancer at 59 in 2013. Ronda is deaf and developmentally disabled and has lived at home all her life. She has been transitioning to a special school in New York City in anticipation of Ramsey’s passing. Ramsey Clark raised her alone after Georgia died. He treasured Ronda and loved to say, “She’s the boss of the house.” His close surviving family members are sister Mimi Clark Gronlund, sister-in-law Cheryl Kessler Clark, three granddaughters Whitney, Taylor and Paige Clark, and extended family.

Rare is such a person as Ramsey Clark with uncompromising defense of true human rights and the courage to defend those beliefs. He will be deeply missed at home and worldwide.