Richard Wright’s 1942 novel was testing the limits of what the white novel-reading public would have found imaginable.

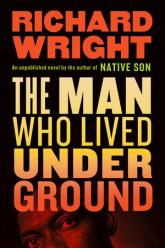

In the sort of coincidence that makes a columnist’s work much easier, the Library of America published Richard Wright’s The Man Who Lived Underground: A Novel on April 20–the same day, as it turned out, that a jury in Minneapolis convicted a police officer of murdering George Floyd last year.

It has taken almost eight decades for Wright’s book finally to appear in print. In an evaluation of the manuscript for Wright’s publisher in 1942, one reader described the opening pages of scenes of police brutality, depicted blow by blow, as “unbearable”–and to revise the text so that it could appear in a literary anthology a couple of years later, Wright cut it by about half. This rendered his short novel into a long short story, with the narrative beginning only after the central character escapes from custody.

The truncated version, which also appeared in a posthumous collection of his short fiction, has been the subject of a substantial body of academic criticism, with the echoes of Dostoevsky and the influence of Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man (not to mention the possible allusions to Plato’s myth of the cave) all duly considered. But largely missing has been a sense of the brutal context of the subsequent narrative’s sometimes dreamlike quality. Reading the work in the form Wright originally intended it to go into the world means facing not only the “unbearable” passages but also the absolute certainly that they were, if anything, understated.

Having now given topicality its due, I’ll venture a guess as to its place in Wright’s work. The Man Who Lived Underground would be among his three or four best books, even if it did not also include another text hitherto only available to scholars consulting the Wright papers at Yale University’s Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library: an essay with the unassuming title “Memories of My Grandmother,” which is certain to be one of Wright’s most discussed writings for at least the next several years.

Toru Kiuchi and Yoshinobu Hakutani’s useful Richard Wright: A Documented Chronology 1908-1960 indicates that he began writing The Man Who Lived Underground in the summer of 1941, a little over a year after his first published novel, Native Son, became an instant best seller. The inspiration came from an article in True Detective, a pulp magazine, about a man who “[got] into various stores in Hollywood by digging a tunnel connecting to the basements and back of the shops.” The culprit was a white man. But the report of his deeds somehow resonated with Wright’s own very complicated feelings about race and religion in African American life in general, and in his grandmother’s life in particular.

When we meet Wright’s underground man at the beginning of the novel, he is a sort of everyman figure called Fred Daniels, which is about as deliberately prosaic a name as you can get. A law-abiding and churchgoing guy, Daniels leaves work on an early Saturday evening with the week’s pay in hand and prepares to go back to the wife who is waiting for him at home–a day or two away from delivering their firstborn. But he has hardly had time to tuck the dollar bills in his pocket before he hears a voice from inside a cop car: “Come here, boy.”

Daniels is picked up by police for no reason they care to explain, at least not until after they’ve taunted and humiliated him on the ride to the station. Once set up in an interrogation room, they beat Daniels senseless while accusing him of a double murder. Every detail is narrated from his point of view, which shifts from bewilderment and disbelief into an almost dissociated state. Nothing he says has any effect except to bring more wrath down on him. The police offer to let Daniels see his wife if he’ll just sign a statement. The whole sequence is disorienting in part from the reader’s helpless certainty that: a) signing a confession is absolutely the worst action he could take, yet b) refusing would mean the very real possibility of dying in custody.

Wright was testing the outer limits of what the white novel-reading public would have found imaginable at the time. The 21st-century reader has no excuse to be so blinkered, given the documentation of police station torture in Chicago or what Derek Chauvin did not mind doing to George Floyd in public while a video camera recorded it. That said, one aspect of the opening that evoked a surprisingly intense reader response in me was the repeated address to Daniels, a man of about 30, as “boy”–a usage loaded with more menace and intention to degrade than it seems one word could express.

Seizing an opportune moment, Daniels gets away from the police long enough to open a manhole and descend into the foul gloom of the sewer system. He finds his way around with a few matches and encounters “a huge rat, wet and coated with slime, blinking beady eyes and showing tiny fangs … its forepaws clawing for a hold on the slick brick.” Daniels has no intention of staying any longer than necessary but also no way to know when returning to the surface will be an option.

He finds his way around by touch (“The wall ended, and his fingers toyed experimentally in space, like the antennae of an insect”) and moves toward sounds of what turns out to be an African American church service, held in a basement and visible through a grate. It is the first of several locations he is able to view, and sometimes to enter, from his place in hiding, where he sets up a makeshift “home” from bits and pieces of what he finds during his exploration.

The narrative of his itinerary is both concrete (full of all-too-tangible details) and phantasmagoric, and at some point while reading, I found the phrase “naturalistic surrealism” coming to mind. It is more or less a contradiction in terms. In naturalistic fiction, characters and actions are depicted within, and as products of, an environment; social conditions and physiological drives are never out of view. With surrealism, the landscape is entirely interior; words and deeds obey no logic but that of a dream or fantasy. Wright’s Native Son is a landmark work of American naturalist fiction, and the rat Fred Daniels sees will remind any reader of the earlier novel of its opening scene in the tenement apartment where Bigger Thomas lives. And the narrative arcs for both Thomas and Daniels are defined by as naturalistic a motive as anyone can be: the drive to self-preservation. (Also bearing note: the comparison of Daniels’s fingers to antennae.)

But with The Man Who Lived Underground, a nightmarish tone is set from the moment Fred Daniels finds himself overpowered and helpless to respond to accusations of guilt for a crime he doesn’t even know about–much the situation facing the central figure in Franz Kafka’s novel The Trial. (Spoiler alert: the parallels do not end there.) But this is less a matter of literary influence than of Wright burrowing in to explore the Kafkaesque circumstance of living in his own skin.

Reading “Memories of My Grandmother” makes explicit that any resemblance between Wright’s novel and surrealism is absolutely inevitable. “Surrealism,” Wright explains, “is a manner of looking at the world, a way of feeling and thinking, a method of discovering relationships between things; it is a phase of the creative process.” Nor was he importing it: “The manner in which Negro blues songs juxtapose unrelated images was the advent of surrealism on the American scene.” Wright returned to this line of thought in later work, but this early formulation of the idea is particularly forceful, as if the ideas are taking shape as he writes:

A black woman, singing the blues, will describe a rainy day, then, suddenly to the same tune and tempo, she will croon of a red pair of shoes; then, without any logical or causal connection, she will sing of how blue and lowdown she feels; the next verse may deal with a horrible murder, the next with a theft, the next with tender love, and so on. This tendency of freely juxtaposing totally unrelated images and symbols and then tying them into some overall concept, mood, feeling, is a trait of Negro thinking and feeling that has always fascinated me. I think it was this part of my grandmother’s personality that fascinated me more than anything else. The ability to tie the many floating items of her environment together into one meaningful whole was the function of her religious attitude. It seemed indicative of a certain strange need on her part.

Connecting Salvador Dalí and his Seventh-Day Adventist grandmother involves quite a leap, but here Wright is feeling his way into strange depths. “Eternity was so real to her,” he recalls, “that human life had an air of unreality … [Her] never-blinking eyes … seemed to be contemplating human frailty from some invulnerable position outside time and space.” They fought–quite a bit, it sounds like–across an enormous psychological distance:

She hovered somewhere off in space so distantly that things that strike us as having no relationship were merged into an organic blur for her, and things that were united for us were either separate or nonexistent for her.

Pious as his grandmother was, she would have resented Wright’s implication that she had anything in common with singers of the blues or paintings in which, e.g., watches melted. And some of his reflections suggest that the author himself only made the connections after writing The Man Who Lived Underground. He writes,

First, I noticed that Fred Daniels was withdrawn from the world; second, that he suffered a loss of contact with reality in a hard and sharp sense; third, that there was a gradual disintegration of his personality. Yet while noticing this, I also noticed that this whole idea of a man withdrawing from the world had a striking similarity to the life of my grandmother, who, in her religious life, was certainly withdrawn from the world as much as anybody has ever been withdrawn from it, as much as anyone can live in this world and not have anything to do with it.

If all this has its surrealist aspect, Wright also has a very clear sense of it as (to put it in naturalistic terms) a survival mechanism. In the much shorter version of the text that readers have known for decades, the story of Fred Daniels opens with him plunging directly into the underworld. We soon learn that the police are on his back. But only now, with the novel in its restored form, do you see how they got inside his head–and all the violence that put them there.

Scott McLemee is the Intellectual Affairs columnist for Inside Higher Ed. In 2008, he began a three-year term on the board of directors of the National Book Critics Circle. From 1995 until 2001, he was contributing editor for Lingua Franca. Between 2001 and 2005, he covered scholarship in the humanities as senior writer at The Chronicle of Higher Education. In 2005, he helped start the online news journal Inside Higher Ed, where he serves as Essayist at Large, writing a weekly column called Intellectual Affairs. His reviews, essays, and interviews have appeared in The New York Times, The Washington Post, The Boston Globe, The Nation, Newsday, Bookforum, The Common Review, and numerous other publications. In 2004, he received the Nona Balakian Citation for Excellence in Reviewing from the National Book Critics Circle. He has given papers or been an invited speaker at meetings of the American Political Science Association, the Cultural Studies Association, the Modern Language Association, and the Organization of American Historians.