A growing number of business and political leaders have found yet another argument to use against federal pandemic relief programs, especially those that provide income support for workers: they hurt the economic recovery by encouraging workers not to work.

In the words of Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell, as reported by BusinessInsider:

“We have flooded the zone with checks that I’m sure everybody loves to get, and also enhanced unemployment,” McConnell said from Kentucky. “And what I hear from businesspeople, hospitals, educators, everybody across the state all week is, regretfully, it’s actually more lucrative for many Kentuckians and Americans to not work than work.”

He went on: “So we have a workforce shortage and we have raising inflation, both directly related to this recent bill that just passed.”

In line with business claims that they can’t find willing workers despite their best efforts at recruitment, the governors of Montana, South Carolina, Alabama, Arkansas, and Mississippi have all announced that they will no longer allow the unemployed in their respective states to collect the $300-a-week federal supplemental unemployment benefit and will once again require that those receiving unemployment benefits demonstrate they are actively looking for work.

In reality there is little support for the argument that expanded unemployment benefits have created an overly worker-friendly labor market, leaving companies unable to hire and, by extension, meet growing demand. But of course, if enough people accept the argument, corporate leaders and their political allies will have achieved their shared goal, which is to weaken worker bargaining power as corporations seek to position themselves for a profitable post-pandemic economic recovery.

Wage trends

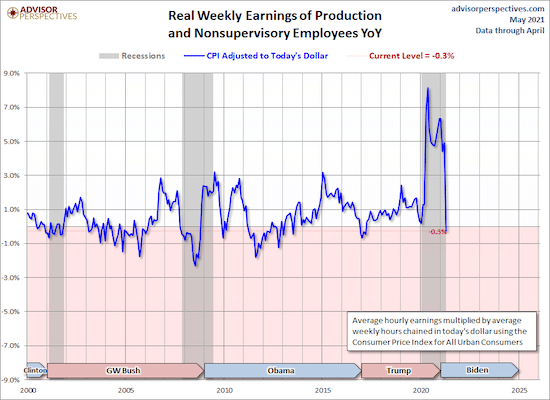

If companies were aggressively seeking workers, we would expect to see the resulting competition push up wages. The following figure shows year-over-year real weekly earnings of production and nonsupervisory workers—approximately 85 percent of the workforce. As we can see, those earnings were actually lower in April 2021 than they were in April 2020.

In short, companies may want more workers, but it is hard to take their cries of anguish seriously if they remain unwilling to offer higher real wages to attract them. Real average weekly earnings of production and nonsupervisory workers in April 2021 stood at $875. Multiplying weekly earnings by 50, gives an estimated annual salary of $43,774. That total is actually 5.7 percent below the similarly calculated peak in October 1972.

Over the last three months, the only sector experiencing significant wage growth due to labor shortages is the leisure and hospitality sector (which includes arts, entertainment, and leisure as well as accommodations and food services). Wages in that sector grew at an annualized rate of nearly 18 percent relative to the previous three months. But, as Josh Bivens and Heidi Shierholz explain,

There is very little reason to worry that labor shortages in leisure and hospitality will soon spill over into other sectors and drive economywide “overheating.” For example, jobs in leisure and hospitality have notably low wages and fewer hours compared to other sectors. Weekly wages of production and nonsupervisory workers in leisure and hospitality now equate to annual earnings of just $20,628, and total wages in leisure and hospitality account for just 4% of total private wages in the U.S. economy. . . . [Moreover] this sector seems notably segmented off from much of the rest of the economy.

Job openings and labor turnover

The figure below, drawn from the Bureau of Labor Statistics’s Job Openings and Labor Turnover Summary (JOLTS), shows the monthly movement in job openings, hires, quits, and layoffs and discharges, with solid lines showing their six-month moving averages.

As we can see, despite business complaints, monthly hiring (green line) still remains greater than during the last years of the pre-pandemic expansion. And although job openings (blue line) are growing sharply while the number of hires is falling, the gap between openings and hires is also still smaller than it was during the last years of the previous expansion. In addition, the number of quits (light blue line), which are an indicator of labor tightness, remain below the last years of the previous expansion and rather stable. In short, there is nothing in the data that suggests business is facing a dysfunctional labor market marked by an unreasonable worker unwillingness to work.

Even with the additional financial support in Biden’s American Rescue Plan, many workers and their families continue to struggle to afford food, housing, and health care. Many workers remain reluctant to re-enter the labor market because of Covid-related health concerns and care responsibilities. Moreover, as Heidi Shierholz points out:

there are far more unemployed people than available jobs in the current labor market. In the latest data on job openings, there were nearly 40% more unemployed workers than job openings overall, and more than 80% more unemployed workers than job openings in the leisure and hospitality sector.

While there are certainly fewer people looking for jobs now than there would be if Covid weren’t a factor . . . without enough job openings to even come close to providing work for all job seekers, it again stretches the imagination to suggest that labor shortages are a core dynamic in the labor market.

We need to discredit this attempt by the business community and its political allies to generate opposition to policies that help workers survive this period of crisis and redouble our own efforts to strengthen worker rights and build popular support for truly transformative economic policies, ones that go beyond the stopgap fixes currently promoted.