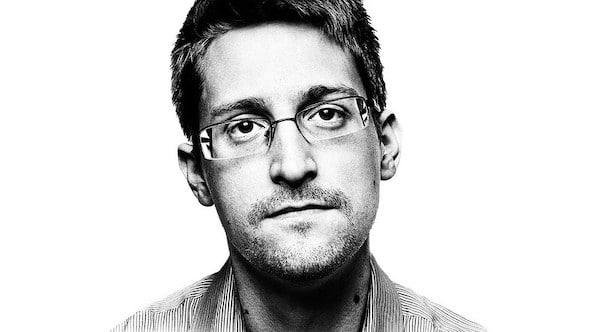

Though his story has been widely disseminated by now, before Edward Snowden fled to Hong Kong he sent a box of classified documents by snail mail from Hawaii (marked mysteriously “from B. Manning”) to a writer in New York, which made its way, unopened, from person to person until it reached journalists Laura Poitras and Glen Greenwald, who went on to meet with Snowden and tell his story of global panoptic surveillance affecting just about everybody online.

Though his story has been widely disseminated by now, before Edward Snowden fled to Hong Kong he sent a box of classified documents by snail mail from Hawaii (marked mysteriously “from B. Manning”) to a writer in New York, which made its way, unopened, from person to person until it reached journalists Laura Poitras and Glen Greenwald, who went on to meet with Snowden and tell his story of global panoptic surveillance affecting just about everybody online.

The story, Snowden’s Box: Trust in the Age of Surveillance, by Jessica Bruder and Dale Maharidge, is, as the authors emphasize, a story of trust in an age of paranoia and suspicion. They’re keen to tell us, tag-team style, how the world has changed since the events of 9/11, with the militarization of the Internet, and the rise of surveillance capitalism, leading to a pervasive sense that privacy is no longer viable. We’ve succumbed to the sad notion that if we have ‘nothing to hide’ then we needn’t worry about Big Brother watching over us.

Many readers will be familiar with Jessica Bruder’s work through the adaptation of her travel memoir, Nomadland, which recently won the Oscar for best film, and for which she worked with the director Chloé Zhao to create a screenplay. Her road travels, living the life of a nomad for months, and talking Studs Terkel-like to American wanderers, travelling from job to job as a lifestyle, jibes quite nicely with co-author Dale Maharidge’s background. Maharidge won the Pulitzer Prize in 1990 for And Their Children After Them, his follow-on to the James Agee study of Alabama sharecroppers, Let Us Now Praise Famous Men. They’re People people, and so are the cadre of journalists and independent filmmakers they hook up with in telling this side story.

The first half of the book retells the now-familiar story of how and why Edward Snowden stole highly classified documents from NSA contractor Booz Allen Hamilton and handed them over to Poitras and Greenwald, who went on to make a film, Citizenfour, and detail his revelations in the Guardian. The co-authors quote Snowden judiciously; in an interview shortly after he outs himself on TV, Snowden tells us that the surveillance state he’s seen represents “an existential threat to democracy… I don’t want to live in a world where there’s no privacy and therefore no room for intellectual exploration and creativity.”

Bruder explains that Snowden had wanted to have his revelations run in the New York Times, the nation’s preeminent paper of record, but was seriously bummed out when they quashed an October 2004 article by James Risen and Eric Lichtblau that exposed Stellar Wind, the government’s illegal dragnet of American electronic communications. The Bush administration had denied such activity.

Bruder writes, “Approaching the New York Times…was out of the question. Snowden didn’t have confidence that the newspaper would have the guts to break the story… The scoop was scheduled to run right before the 2004 elections, but Executive Editor Bill Keller deferred to Bush administration officials, who claimed the revelations would damage national security.” When the story finally broke, more than a year later, it caused a political furor and popular outcry.

A more intriguing section in Snowden’s Toolbox comes when Bruder talks about how Poitras and Greenwald got together after the Snowden revelations began running in the Guardian and were invited by Ebay billionaire Pierre Omidyar to start up a new publication–The Intercept. It was meant to be a solid alternative to the corporatized MSM and a trustworthy reporting platform for whistleblowers. The publication garnered and poached some of the best journalistic talent from NYT and WaPo and elsewhere and seemed, at first, like the Travelling Wilburys of journalism.

But there was trouble from the start. The Terms of Service (TOS) made it clear that readers could be expected to have their presence at the site logged and their comments scanned by Google Adsense and Amazon’s algorithms. Such surveillance was troublesome, if for no other reason than that the Intercept’s readership were probably the types the State would want to gather details about.

It recalled the deal that Greenwald had signed with Amazon to promote his Pulitzer Prize-winning post-Snowden account of the surveillance state, No Place to Hide. Viewers of the site were offered an opportunity to receive Greenwald’s book for free, if they applied and were successfully approved for an Amazon credit card. The application details would be processed by Chase, who Greenwald had once excoriated for their corrupt practices. But more importantly, by accepting the deal from Amazon, Greenwald was effectively promoting the forwarding of private information to a corporation that would collect and store that data–from exactly the kind of readers the State would be eager to parse.

We learn that Laura Poitras, co-founder of The Intercept, was turned down when she wanted to continue working with the Snowden trove of documents, which First Look Media, owner of The Intercept, told her “the company would own all rights to any publication that resulted from our writing about the Snowden archive.” And that, she continues, “Notes we took at the archive would be confiscated for review–and possible redaction–by the Intercept.” And she added: “I laughed. The experience felt like something out of Kafka. And it gave me a sense of déjà vu, echoing how the NSA and the FBI had shut down our request to see our files.” The Intercept has since stopped writing altogether about the Snowden archive.

It gets worse when the reader learns that Laura Poitras was stiffed by The Intercept in her compensation package. Bruder writes, “Laura had been facing challenges of her own at the company, including the startling realization that her compensation was far below that of her male colleagues Greenwald and (Jeremy) Scahill.” Unbeknownst to her, Scahill and Greenwald had renegotiated their contracts, and the resulting pay disparity was “in the hundreds of thousands of dollars.”

Toward the end of the book, Bruder and Maharidge, the leit motif is repeated. Trust–at the interpersonal level, work environment and social contract with the State–is key. They write,

Trust is the basis of all cooperative action in a free society. It’s the feeling of fellowship that allows people to take risks and grow. It’s also the underpinning of democracy. And it’s fragile, easy to undermine.

Succinct, true, and well put.

All in all, Snowden’s Toolbox is a good read, with humor, intelligence, and a welcome sense of journalistic collegiality. An Appendix offers a “toolbox” of stuff journalists and readers can do to maintain their privacy and the documents of their whistleblowing sources.

John Hawkins is an American freelance journalist currently residing in Australia. His poetry, commentary, and reviews have appeared in publications here, in Europe, and in the USA. He is a regular contributor to Counterpunch magazine.