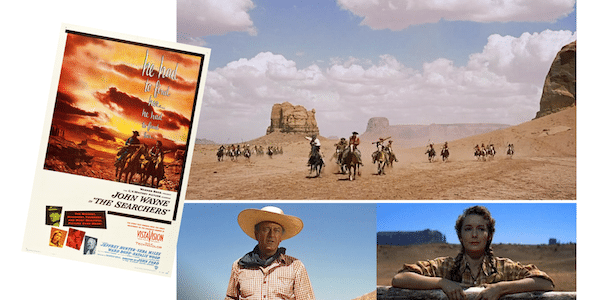

“It just so happens we be Texicans,” says Mrs. Jorgensen, an older woman wearing her blond hair in a tight bun, to rough-and-tumble cowboy Ethan Edwards in the 1956 film The Searchers. Mrs. Jorgensen, played by Olive Carey, and Edwards, played by John Wayne, sit on a porch facing the settling dusk sky, alone in a landscape that is empty as far as the eye can see: a sweeping desert vista painted with bright orange Technicolor. Set in 1868, the film lays out a particular telling of Texas history, one in which the land isn’t a fine or good place yet. But, with the help of white settlers willing to sacrifice everything, it’s a place where civilization will take root. Nearly 90 years after the events depicted in the film, audiences would come to theaters and celebrate those sacrifices.

“A Texican is nothing but a human man way out on a limb, this year and next. Maybe for 100 more. But I don’t think it’ll be forever,” Mrs. Jorgensen goes on.

Someday this country’s going to be a fine, good place to be. Maybe it needs our bones in the ground before that time can come.

There’s a subtext in these lines that destabilizes the Western’s moral center, a politeness deployed by Jorgensen that keeps her from naming what the main characters in the film see as their real enemies: Indians.

In the film, the Comanche chief, Scar, has killed the Jorgensens’ son and Edwards’ family, and abducted his niece. Edwards and the rest of Company A of the Texas Rangers must find her. Their quest takes them across the most treacherous stretches of desert, a visually rich landscape that’s both glorious in its beauty and perilous given the presence of Comanche and other Indigenous people. In the world of the Western, brutality is banal, the dramatic landscape a backdrop for danger where innocent pioneers forge a civilization in the heart of darkness.

The themes of the Western are embodied by figures like Edwards: As a Texas Ranger, he represents the heroism of no-holds-barred policing that justifies conquest and colonization. While the real Texas Rangers’ history of extreme violence against communities of color is well-documented, in the film version, these frontier figures, like the Texas Rangers in The Searchers or in the long-running television show The Lone Ranger, have always been portrayed as sympathetic characters. Edwards is a cowboy with both a libertarian, “frontier justice” vigilante ethic and a badge that puts the law on his side, and stories in the Western are understood to be about the arc of justice: where the handsome, idealized male protagonist sets things right in a lawless, uncivilized land.

The Western has long been built on myths that both obscure and promote a history of racism, imperialism, toxic masculinity, and violent colonialism. For Westerns set in Texas, histories of slavery and dispossession are even more deeply buried. Yet the genre endures. Through period dramas and contemporary neo-Westerns, Hollywood continues to churn out films about the West. Even with contemporary pressures, the Western refuses to transform from a medium tied to profoundly conservative, nation-building narratives to one that’s truly capable of centering those long victimized and villainized: Indigenous, Latinx, Black, and women characters. Rooted in a country of contested visions, and a deep-seated tradition of denial, no film genre remains as quintessentially American, and Texan, as the Western, and none is quite so difficult to change.

*

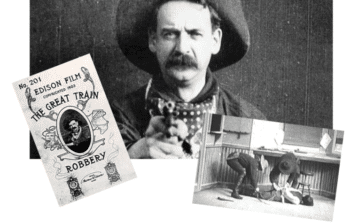

W ith origins in the dime and pulp novels of the late 19th century, the Western first took to the big screen in the silent film era. The Great Train Robbery, a 1903 short, was perhaps the genre’s first celluloid hit, but 1939’s Stagecoach, starring Wayne, ushered in a new era of critical attention, as well as huge commercial success. Chronicling the perilous journey of a group of strangers riding together through dangerous Apache territory in a horse-drawn carriage, Stagecoach is widely considered to be one of the greatest and most influential Westerns of all time. It propelled Wayne to stardom.

During the genre’s golden age of the 1950s, more Westerns were produced than films of any other genre. Later in the 1960s, the heroic cowboy character—like Edwards in The Searchers—grew more complex and morally ambiguous. Known as “revisionist Westerns,” the films of this era looked back at cinematic and character traditions with a more critical eye. For example, director Sam Peckinpah, known for The Wild Bunch (1969), interrogated corruption and violence in society, while subgenres like spaghetti Westerns, named because most were directed by Italians, eschewed classic conventions by playing up the dramatics through extra gunfighting and new musical styles and creating narratives outside of the historical context. Think Clint Eastwood’s The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly (1966).

In the wake of the anti-war movement and the return of the last U.S. combat forces from Vietnam in 1973, Westerns began to decline, replaced by sci-fi action films like Star War s (1977). But in the 1990s, they saw a bit of rebirth, with Kevin Costner’s revisionist Western epic Dances With Wolves (1990) and Eastwood’s Unforgiven (1992) winning Best Picture at the Academy Awards. And today, directors like the Coen brothers (No Country for Old Men, True Grit) and Taylor Sheridan (Hell or High Water, Wind River, Sicario) are keeping the genre alive with neo-Westerns set in modern times.

Still, the Old West looms large, says cultural critic and historian Richard Slotkin. Today’s Western filmmakers know they are part of a tradition and take the task seriously, even the irreverent ones like Quentin Tarantino. Tarantino called Django Unchained (2012) a spaghetti Western and, at the same time, “a Southern.” Tarantino knows that the genre, like much of American film, is about violence, and specifically racialized violence: The film, set in Texas, Tennessee, and Mississippi, flips the script by putting the gun in the hand of a freed slave.

Slotkin has written a series of books that examine the myth of the frontier and says that stories set there are drawn from history, which gives them the authority of being history. “A myth is an imaginative way of playing with a problem and trying to figure out where you draw lines, and when it’s right to draw lines,” he says. But the way history is made into mythology is all about who’s telling the story.

Slotkin’s work purports that the logic of westward expansion is, when boiled down to its basic components, “regeneration through violence.” Put simply: Kill or die. The very premise of the settling of the West is genocide. Settler colonialism functions this way; the elimination of Native people is its foundation. It’s impossible to talk about the history of the American West and of Texas without talking about violent displacement and expropriation.

“The Western dug its own hole,” says Adam Piron, a film programmer at the Sundance Indigenous Institute and a member of the Kiowa and Mohawk tribes. In his view, the perspectives of Indigenous people will always be difficult to express through a form tied to the myth of the frontier. Indigenous filmmakers working in Hollywood who seek to dismantle these representations, Piron says, often end up “cleaning somebody else’s mess … And you spend a lot of time explaining yourself, justifying why you’re telling this story.”

While the Western presents a highly manufactured, racist, and imperialist version of U.S. history, in Texas, the myth of exceptionalism is particularly glorified, perpetuating the belief that Texas cowboys, settlers, and lawmen are more independent, macho, and free than anywhere else. Texas was an especially large slave state, yet African Americans almost never appear in Texas-based Westerns, a further denial of histories. In The Searcher s, Edwards’ commitment to the white supremacist values of the South is even stronger than it is to the state of Texas, but we aren’t meant to linger on it. When asked to make an oath to the Texas Rangers, he replies: “I figure a man’s only good for one oath at a time. I took mine to the Confederate States of America.” The Civil War scarcely comes up again.

The Texas Ranger is a key figure in the universe of the Western, even if Ranger characters have fraught relationships to their jobs, and the Ranger’s proliferation as an icon serves the dominant Texas myth. More than 300 movies and television series have featured a Texas Ranger. Before Chuck Norris’ role in the TV series Walker, Texas Range r (1993-2001), the most famous on-screen Ranger was the titular character of The Lone Ranger (1949-1957). Tonto, his Potawatomi sidekick, helps the Lone Ranger fight crime in early settled Texas.

Meanwhile, the Ranger’s job throughout Texas history has included acting as a slave catcher and executioner of Native Americans. The group’s reign of terror lasted well into the 20th century in Mexican American communities, with Rangers committing a number of lynchings and helping to dispossess Mexican landowners. Yet period dramas like The Highwaymen (2019), about the Texas Rangers who stopped Bonnie and Clyde, and this year’s ill-advised reboot of Walker, Texas Ranger on the CW continue to valorize the renowned law enforcement agency. There is no neo-Western that casts the Texas Ranger in a role that more closely resembles the organization’s true history: as a villain.

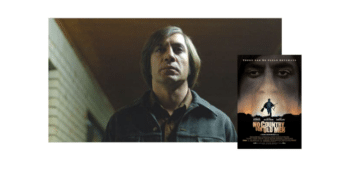

The Coen brothers’ No Country for Old Men (2007) ushered in the era of neo-Westerns set in modern times.

Ushered in by No Country for Old Men (2007), also set in Texas, the era of neo-Westerns has delivered films that take place in a modern, overdeveloped, contested West. Screenwriter Taylor Sheridan’s projects attempt to address racialized issues around land and violence, but they sometimes fall into the same traps as older, revisionist Westerns—the non-white characters he seeks to uplift remain on the films’ peripheries. In Wind River (2017), the case of a young Indigenous woman who is raped and murdered is solved valiantly by action star Jeremy Renner and a young, white FBI agent played by Elizabeth Olsen. Sheridan’s attempt to call attention to the epidemic of missing and murdered Indigenous women still renders Indigenous women almost entirely invisible behind the images of white saviors.

There are directors who are challenging the white male gaze of the West, such as Chloé Zhao, whose recent film Nomadland dominated the 2021 Academy Award nominations. In 2017, Zhao’s film The Ride r centered on a Lakota cowboy, a work nested in a larger cultural movement in the late 2010s that highlighted the untold histories of Native cowboys, Black cowboys, and vaqueros, historically Mexican cowboys whose ranching practices are the foundation of the U.S. cowboy tradition. And Concrete Cowboy, directed by Ricky Staub and released on Netflix in April, depicts a Black urban horse riding club in Philadelphia. In taking back the mythology of the cowboy, a Texas centerpiece and symbol, perhaps a new subgenre of the Western is forming.

Despite new iterations, the Western has not been transformed. Still a profoundly patriotic genre, the Western is most often remembered for its classics, which helped fortify the historical narrative that regeneration through violence was necessary for the forging of a nation. In Texas, the claim made by Mrs. Jorgensen in The Searchers remains a deeply internalized one: The history of Texas is that of a land infused with danger, a land that required brave defenders, and a land whose future demanded death to prosper.

In Westerns set in the present day, it feels as if the Wild West has been settled but not tamed. Americans still haven’t learned how to live peacefully on the land, respect Indigenous people, or altogether break out of destructive patterns of domination. The genre isn’t where most people look for depictions of liberation and inclusion in Texas. Still, like Texas, the Western is a contested terrain with an unclear future. John Wayne’s old-fashioned values are just one way to be; the Western is just one way of telling our story.

Nic Yeager is the culture fellow at the Observer and the author of the guidebook 111 Places in Austin That You Must Not Miss.