Phoenix Express 2021 (PE21), a 12-day U.S.-Africa Command (AFRICOM)-sponsored military exercise involving 13 states in the Mediterranean Sea, concluded on Friday, May 28. It had kicked off from the naval base in Tunis, Tunisia, on May 16. The drills in this exercise covered naval maneuvers across the stretch of the Mediterranean Sea, including on the territorial waters of Egypt, Libya, Tunisia, Algeria, Morocco and Mauritania.

The regimes in these countries, which cover the entire northern and northwestern coastline of Africa, participated in the drill–one of the three regional maritime exercises conducted by the U.S. Naval Forces Africa (NAVAF). Belgium, France, Greece, Italy, Malta and Spain were the European states that participated in the drill.

Among the heavyweights deployed in the exercises was the U.S. navy’s USS Hershel “Woody” Williams (ESB 4). The 784-feet-long warship is a mobile military base which “provides for accommodations for up to 250 personnel, a 52,000-square-foot flight deck.. and supports MH-53 and MH-60 helicopters with an option to support MV-22 tilt-rotor aircraft,” according to the Woody Williams Foundation.

The platform has an aviation hangar and flight deck that include four operating spots capable of landing MV-22 and MH-53E equivalent helicopters.

When the warship entered into its maiden service with the U.S. navy in 2017, Capt. Scot Searles, strategic and theater sealift program manager at the Program Executive Office (PEO) Ships, said,

The delivery of this ship marks an enhancement in the Navy’s forward presence and ability to execute a variety of expeditionary warfare missions.

The Algerian National Navy frigate El Moudamir (F911), Egyptian Navy frigate Toushka (F906) and Royal Moroccan Navy multi-mission frigate Sultan Moulay Ismail (FF 614) were also part of PE21, bringing with them a range weapon systems including surface-to-surface and surface to air missiles, torpedo launchers, heavy naval guns and naval radars.

According to a press release by the U.S. navy, the purpose of this exercise was to test the ability of the participants “to respond to irregular migration and combat illicit trafficking and the movement of illegal goods and materials.”

Smugglers moving goods across the border also illicitly traffic migrants fleeing war or economic crisis in their home countries. AFRICOM has on multiple occasions acknowledged that instability in Libya is the driving force behind the migration crisis.

Who is destabilizing the region?

While ‘Russian intervention’ is blamed for the instability in Libya, AFRICOM played a key military role in the Libyan war in 2012, deposing Muammar Gaddafi, who was a staunch opponent of expanding U.S. military footprint in the region, with the help of radical Islamist organizations. With the exception of Algeria, all the other north African states which participated in PE21 had supported this war in Libya, which has led to mass distress migration.

Many Islamist organizations which emerged amid the anarchy caused by the war were also used by the U.S. and its allies in the Syrian war in a bid to overthrow president Bashar al-Assad, triggering another major wave of destabilization and migration.

Noting that “Syrians.. have (also) entered Libya from neighboring Arab states seeking onward transit to refuge in Europe and beyond,” a U.S. Congressional Research Service report states:

The International Organization for Migration (IOM) reports that nearly 654,000 migrants are in Libya, alongside more than 401,000 internally displaced persons and more than 48,000 refugees and asylum seekers from other countries identified by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR).

The report in 2020 acknowledged that with “human trafficking and migrant smuggling.. trade has all but collapsed compared with the pre-2018 period.”

This migration wave, caused in no small part by AFRICOM-coordinated military interventions in Libya, has since been purported as a reason for further militarization of the region through such exercises as PE21 sponsored by AFRICOM.

The hysteria surrounding migration whipped up by right-wing parties has provided politically fertile ground for the U.S. to mobilize state militaries for such drills. This is despite a fall in undocumented migration.

The need to respond to ‘irregular migration’ with warships is one of the official pretexts which, like the ‘war on terror’, has been used to further the militarization of Africa through AFRICOM since it was established in 2007.

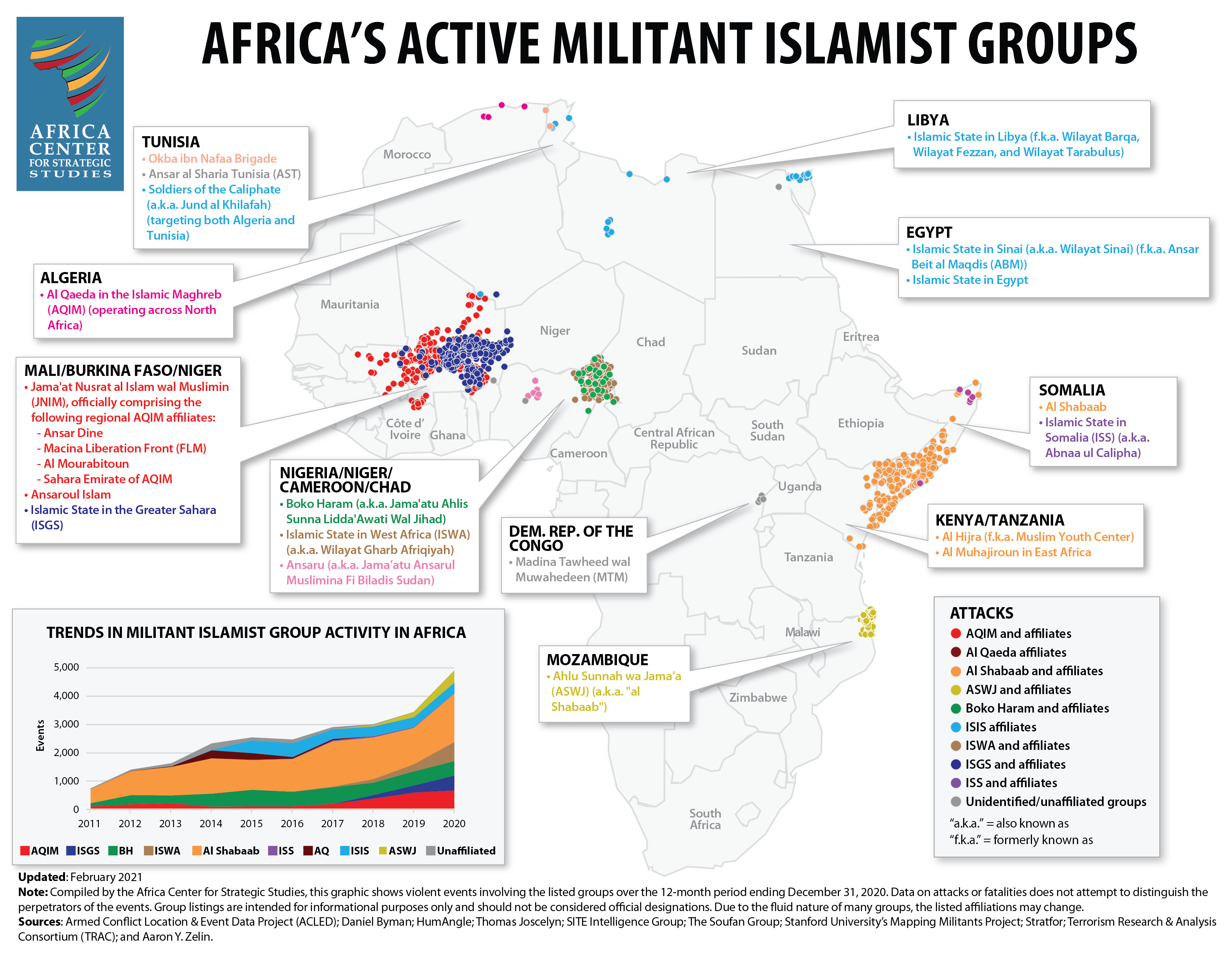

Meanwhile, notwithstanding the fact that the main cause behind the explosion of terrorist organizations in the region was the 2011 Libyan war in which AFRICOM itself was an aggressor, it continues to be portrayed as a bulwark against terrorist organizations. Its operations in Africa over the last decade, including hundreds of drone strikes, correlate with a 500% spike in incidents of violence attributed to Islamist terrorist organizations.

The Chinese boogeyman

Another justification given by the U.S. for AFRICOM is the perception of a growing Chinese influence. “Chinese are outmaneuvering the U.S. in select countries in Africa,” General Stephen Townsend, commander of AFRICOM, told Associated Press late in April, less than three weeks before the start of PE21.

He went on to claim that the Chinese are “looking for a place where they can rearm and repair warships. That becomes militarily useful in conflict. They’re a long way toward establishing that in Djibouti. Now they’re casting their gaze to the Atlantic coast and wanting to get such a base there.”

Calling out the lack of credibility of this claim, Eric Olander, a veteran journalist and co-founder of The China-Africa Project, wrote: “The Chinese are looking for a base but he doesn’t provide any specifics or any evidence to back up the claim. Again, we’ve heard this before… for years in fact. For all we know the general doesn’t have any more refined intelligence than the same speculation that’s been floating around African social media all these years about a new Chinese base in Namibia or was it Kenya or maybe Angola?”

Townsend also pointed to the Chinese investments in several development projects in Africa. “Port projects, economic endeavors, infrastructure and their agreements and contracts will lead to greater access in the future. They are hedging their bets and making big bets on Africa,” he claimed.

This has been disputed by Deborah Bräutigam, director of the China Africa Research Initiative at Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies, who concluded that China’s economic engagements in Africa are not of a predatory nature.

Bräutigam argues that Chinese economic engagements on the continent are very much in line with the economic interests of these African states, providing jobs to locals and improving public infrastructure.

Neither the concocted threat of Chinese domination of Africa, nor terrorism and irregular migration add up to the raison d’etre of AFRICOM. As former AFRICOM commander Thomas Waldhauser explained to the House Armed Services Committee in 2018, the purpose of AFRICOM is to enable military intervention to propagate “U.S. interests” across the continent, “without creating the optic that U. S. Africa Command is militarizing Africa.” However, the 5,000 U.S. military personnel and 1,000 odd Pentagon employees deployed across a network of 29 bases of AFRICOM in north, east, west and central Africa present a different picture.

AFRICOM has its headquarters in Stuttgart, Germany, which sponsored PE21. While this exercise was still underway, preparations for African Lion 21, Africa’s largest military exercise, had already begun.