Janine Jackson interviewed Free Press’s Joseph Torres about media and the Tulsa Massacre for the June 4, 2021, episode of CounterSpin. This is a lightly edited transcript.

Janine Jackson: The night just passed of May 31 into June 1 marks a deeply painful anniversary in the lives of Black Americans. Listeners will have heard, some for the first time, of the 1921 massacre in Tulsa, Oklahoma—18 hours of terrible violence in which at least 300 women, men and children were murdered. Their killings sparked by a newspaper article about a 19-year-old Black shoeshiner, Dick Rowland, falsely accused of assaulting a 17-year-old white girl, but kindled by the white supremacy endemic in U.S. society and culture. Businesses, churches, doctor’s offices and groceries in the area known as Black Wall Street or Little Africa were destroyed, along with the homes of more than 10,000 Black Tulsans.

Afterward, papers like the Tulsa World explained things in ideas listeners will recognize, even if the language is outré. Mayor T. D. Evans was quoted:

Let the blame for this Negro uprising lie right where it belongs—on those armed Negros and their followers who started this trouble and who instigated it. And any persons who seek to put half the blame on the white people are wrong, and should be told so in no uncertain language.

The newspaper called on “the innocent, hardworking colored element of Tulsa” to “cooperate fully and with vast enthusiasm” with officials, and “band themselves together for their own protection against this element of non-working, worthless Negros.” And, yeah, there’s a lot more.

So who decides what we know about Tulsa, and what we retain of what we’re supposedly learning now—and, then, how that changes anything? We’re joined now by Joseph Torres, senior director of strategy and engagement at the group Free Press, and co-author with Juan González of the crucial book News for All the People: The Epic Story of Race and the American Media. He joins us now by phone from Maryland. Welcome back to CounterSpin, Joe Torres.

Joseph Torres: Thank you, Janine. Thank you for having me.

JJ: Listeners will feel the thud of recognition to hear that after the massacre in Tulsa—in which 300 overwhelmingly Black people were killed, and some 800 shot or wounded—the headline of the Tulsa World was “Two Whites Dead in Race Riot.”

The story of Tulsa, of Greenwood, then as now, is, importantly, a story about media: about what newspapers told people, and they believed, at the time; and then, afterward, what folks were told to remember and told to forget. You wrote about it recently for Free Press, and I would refer listeners to that piece, but talk a little, if you would, about the role of journalism in the Tulsa massacre.

JT: The role of the two main daily papers—the Tulsa World, which was the morning paper, and the Tulsa Tribune, the afternoon paper—were critical. The Tulsa Tribune, for example, in the so-called light that sparked the massacre, but in the initial days afterwards as well, and in going forward in the cover-up, making sure the story is basically forgotten in our society.

Joseph Torres: “When we think about white power structures in our society, when we think about hierarchies…the media companies are a part of that system, always have been.”

So the Tulsa Tribune was owned by a publisher named Richard Lloyd Jones. When we think about white power structures in our society, when we think about hierarchies and white racial hierarchies in the society, the media companies are a part of that system, always have been, and this was a case in point. So the paper is very sympathetic, the Tulsa Tribune, to the KKK, basically prints an advertisement about the KKK’s plans to come into Oklahoma. And then it focuses its coverage, more so in May, on issues of crime and criminality; they normally ignored Black folks in Tulsa, unless it dealt with crime.

JJ: Mmm-mm.

JT: But they started focusing more on a campaign of Black lawlessness in the Greenwood district. But the night, as you mentioned in the intro, the May 31 headline of the false attack of Dick Rowland on a white teenage girl, lights the spark that results in a white mob heading down to the courthouse to demand that Rowland be handed over to them and basically lynched.

JJ: Mmm-mm.

JT: There’s an editorial that many believe was actually published in that paper as well, that was predicting a lynching that night. But that editorial, in years later, and also that front-page story about the alleged rape, disappeared from the microfilm when they went to record the paper for historical purposes. But eyewitnesses and folks who were alive at the time remember that editorial.

JJ: Right.

JT: So there was this daily news story that was very sensational in its details of this alleged rape, and then predicting a lynching that night, lit the match of thousands of white people actually going to the courthouse, and the massacre itself. Thousands of white people invaded Greenwood and torched the whole place.

And then, following that, the Tulsa World—which is still in existence today; it’s still the daily paper in Tulsa—all this language, both papers are saying, you know, “We’ve got to get rid of these ‘bad n-words’” in their community, right?

JJ: Right.

JT: It was a purposeful attempt to blame Black folks, because what happened as well, the last important detail, is that there was never a person who was lynched in Tulsa, I believe, who was Black, to that point. And so Black residents grabbed their arms—a lot of them were former World War I veterans—and they went down to the courthouse and asked the police if they needed help to protect Dick Rowland from being lynched. They were declined twice.

And so the newspapers blamed Black folks, who brought their guns to try to protect someone from being lynched, as the “agitators” of this, and that’s how they framed it: It was the Black community that was the reason this happened, and it brought great shame on Tulsa; now the Tulsa white community was responding and trying to rebuild, and Black folks needed to be very appreciative of this effort, and get rid of—as you were mentioning—those leaders that they followed.

And a lot of those leaders, including two Black newspapers, were burned down as well: the Tulsa Star and the Oklahoma Sun. [Star publisher] A.J. Smitherman was a very prominent member of the Black community in Tulsa, a very powerful person, and he eventually fled the state because he was actually charged, the Black folks in the community were charged, for instigating the massacre. And A.J. Smitherman left the state and he printed papers in Buffalo, New York, where he died.

JJ: You talk about the erasing of the incendiary editorial. And there’s been a kind of general erasure of what happened in Tulsa. It’s kind of strange to hear folks saying “the little-known,” you know, “this invisible history,” and I think, ‘Well, I know a lot of Black people who’ve been knowing about Tulsa.” But it’s true that it is, more widely speaking (or, among white people), it is hidden history. And that has something to do with media, too. I mean, there’s just been a lot of silence around this story.

JT: Yes, it was an intentional campaign. The Tulsa Tribune, which no longer exists, didn’t mention the massacre until 50 years later; there were efforts to cover it up. There was this white reporter, back in 1971, who was asked—unbelievably, by the Tulsa Chamber of Commerce—to write something and commemorate what happened on the 50th anniversary. And he started researching this story. And he started getting basically threatened by strangers that would approach him on the street and tell him not to write the story; calls to his house; someone wrote on his car windshield with a bar of soap, “Better look under your hood,” I believe was written, right?

JJ: Wow.

JT: One of the things he stated in interviews is that there were still people who were alive, who might be very prominent members of the community, who actually took part in the massacre. And you just think about it: The children of those folks, because thousands of people, literally, took part in this massacre, everyday folks in Tulsa, and police deputized—we might be declined, Black folks, from trying to protect Dick Rowland, right—they deputized white folks to go into Greenwood, set the place on fire, which they did. And then they put thousands of Black folks in concentration camps following that; they just rounded up everybody. And so a lot of these folks’ children still may be alive as well, and grandchildren.

So you can see how a cover-up happens, right, because the powers that be in the city are going to be totally implicated. And for the newspapers, obviously, they played a role; they played a role in there. Matter of fact, when that publisher died, there was no mention in the paper at all of his role in the Tulsa massacre.

So this is how it happens. And how is this really different than what Nikole Hannah-Jones is going through on the issue of tenure in North Carolina? And all this attack against critical race theory; it’s all the same thing. We have to keep that stuff buried in the past and not remember it, because if we remember it, there’s a potential that you have to, when you reconcile with something, it can be a call for repair, right?

JJ: Yep.

JT: And folks don’t want to address the “repair” part, like: What do reparations look like? How do you make a community whole like Greenwood? It was a community that was self-sustaining, that had everything it needed in that community, and it was destroyed.

Again, you need a narrative, right? That’s the whole thing with media: You need narratives. You need narratives to dehumanize people, you need narratives to justify the massacre of people, and then you need narratives to talk about how white folks in this community were coming to the aid of those who were harmed, and they’re the ones who are the heroes in the narratives.

And often, not telling the story is— not only do you need a narrative to give you political cover, but then, not telling the story is another way of just total erasure, right?

JJ: Absolutely.

JT: Of course.

JJ: Yeah.

JT: It’s still going on: This whole 1619 struggle, just to recognize very basic facts in our nation’s history, and you can see the backlash. Because at the end of the day, in my personal opinion, the question is whether a multiracial democracy, which democracy has never been fully realized, is actually possible? Right?

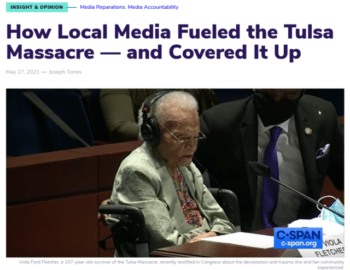

And when you have to reconcile with these stories in history, there’s going to, of course, be calls for repair, you know? And that’s one thing we don’t want to do as a country, right? We don’t want to repair. I believe even Joe Biden (correct me if I’m wrong) yesterday, when he went to Tulsa, he didn’t even mention anything about reparations for… There are three living survivors; they are three Black folks—who are 107, 106 and 100—who survived the massacre, and one of them, Ms. Fletcher, testified in Congress that she is still financially struggling.

JJ: Viola Ford Fletcher, 107 years old…

JT: Yes.

JJ: …she was seven, saying she’s slept with the lights on ever since, “because if I don’t have the lights on, how, how will I see to get out of my house?” It’s too much to even get your brain around the harm—and it’s living history.

So I just want to come back to that question of bringing it into the present, because, OK, right now, there are stories on stories on this. Some are folks like DeNeen Brown, who’s been on it for decades, right? And then, OK, here’s the Wall Street Journal, talking about multigenerational reverberations on family wealth in Tulsa. Here’s USA Today, talking about how, oh, you know it’s “not just Tulsa”; “racist mobs” (that’s their language) have been a “widespread and constant concern.” We’ve got TV projects with LeBron James; we’ve got curricula.

All right. So everybody who is invested in wanting this country to change knows that you take your shot when there’s an opening; we need understanding all the time, but you take your shot where there’s an opening.

But right now, it seems like we’re saying, “Look at Tulsa: It’s an example of the depth and the breadth of the hatred, of the intergenerational harm…”

JT: Right.

JJ: “…of the lie, and of the silencing and gaslighting and censoring.”

And I fear that what some folks are taking via the media is, “Tulsa, what a crazy exceptional episode in U.S. history,” you know, “Thank goodness, we aren’t like that anymore.”

It matters, not just to tell the story, but to show that it’s not just story, you know? And so I’m just wondering, like—I’m not negative on it; I appreciate the attention…

JT: Yes.

JJ: …I appreciate the spotlight; my question is: What’s going to be left behind when media move away, when they’re not talking about Watchmen, when they move away from the story of Tulsa, what’s going to be the sediment? What’s going to be learned from it?

JT: Yeah, that’s the thing. I feel privileged and honored to be able to work on a project called Media 2070 that the Black Caucus at Free Press created, which calls for media reparations for the Black community. And a part of reparations is reconciling and repair.

For us, for myself, speaking for myself, the idea is that we have to address narratives in the history of anti-Black racism in the media system, and narrative that’s been intentionally weaponized in order to further white racial hierarchies in society.

When you think about the federal government now, when we think about broadcasting, we think about broadband, it’s been a policy of exclusion; it’s been a policy of excluding Black folks and other communities of color from ownership of our nation’s infrastructure. Powerful institutions have been created by using our public airwaves, by the roads that we dig up, and the broadband that we lay underneath the ground, and that’s our rights of way, have been used to generate great wealth, and cause great harm to our communities by the stories that these institutions tell.

JJ: Media 2070—which is a project that I’m also a part of…

JT: Yes.

JJ: —it begins, at least, with dialogue, and with an understanding: Corporate news media are forever telling us we’re doing a “racial reckoning” in this country. And you think, “Well, what does that mean, an actual ‘reckoning’?” It has to mean a really dry-eyed, clear conversation that includes actual history, and not whitewashed history.

And that’s why I think Tulsa is a chance for news media, to say, “How seriously are you going to do this? Are you going to really tell the truth? Are you going to really lift this up and continue to acknowledge the lessons that come from this?” Or are you going to say, “This is a weird exception that happened in history, and we’re only going to remember it now because it’s the 100th anniversary”?

JT: Well, yes, that’s how this stuff often works. People are much more comfortable with stuff that happened in the past, right? As opposed to dealing with their own—you know, the news media have to deal with their own hierarchies, the idea of, over the year since George Floyd as well, the racial uprisings that began to happen last year, including newspapers, like the New York Times and the Tom Cotton editorial, and the Philadelphia Inquirer firing its editor after the whole “Buildings Matter, Too” headline.

JJ: Right.

JT: The idea is that even news institutions are invested in a white racial hierarchy, and so it’s difficult for them to want to address anti-Black racism when they have to address their own hierarchies. And so we have to do that to reduce harm, right?

But also, can we also dream of a world where we have an abundance of resources that fund Black-owned media platforms that control the creation and distribution of their own narratives, and that are tethered to serving their community? We have to dream of these new possibilities, while also trying to prevent further harm from happening from these institutions that continue to harm us.

It’s always a struggle to hold folks accountable, to hold institutions accountable; that’s what we have to continue to do. And I don’t know how you feel, Janine; you’ve been doing this for a long time. But at times I feel hopeful, in the sense that we’re actually having this debate. I hate to see Nikole Hannah-Jones struggling just to get tenure, but there is a public fight happening.

JJ: Absolutely. I think we’re ahead of where we’ve been. I think we’ve got a lot of forces that we can marshal as we push forward.

JT: Yeah. So that’s what we’re trying to do with Media 2070. And we had this press briefing for Media 2070 with the new Tulsa Star, which is the new platform for covering the community. So there are a lot of folks doing amazing work out there, amazing journalists who are doing justice-based journalism, movement-based journalism.

There are a lot of folks who are trying to use journalism for a force of good, and of course a lot of journalists of color and Black journalists who work at our major media institutions, who are doing their best against tough cultural circumstances within their newsrooms to continue to make sure these stories are told. All the stories we’re seeing now, which is a good thing, about Tulsa, it’s because folks are really advocating in newsrooms to make sure this story is not forgotten.

JJ: We’ve been speaking with Joseph Torres. He’s senior director of strategy and engagement at the group Free Press, and co-author of the necessary book, News for All the People. His piece on Tulsa is up on FreePress.net. Joe Torres, thank you so much for joining us this week on CounterSpin.

JT: Thank you, Janine, appreciate it. Thank you so much.