Since the October Revolution, Marxism has experienced almost as many crises as capitalism itself. Crises are Marxism’s bread and butter, if not its chalk and cheese. Meltdowns of capitalism usually come as little surprise to savvy Marxist theorists, who’d seen it all coming long ago, even while those capitalist economies basked in booming glory. But economic crises are one thing; economic crisis plus a global pandemic is something else again, beyond an everyday capitalist norm, more akin to the political-economy of wartime. And for a thought that fuses theory and praxis, pandemic, like war, threatens not only life and limb, but also solidarity and tender acts of human togetherness.

But there’s another aspect to pandemic as well as to a Marxism of pandemic: the delicate balance between the individual and society is disrupted, between a liberty at the personal level and the needs of a society at the population level—the scale of much epidemiological enquiry. Pandemics necessitate that public health exigencies assume priority, even at the expense of the liberty of the person. Willy-nilly, collective rights find themselves clashing with individual rights, and not always to everyone’s liking—especially in lands where personal freedom is touted as sacrosanct. We’ve seen this most starkly expressed in the conflict over face-mask wearing, where protecting other people is seen by some as a downshifting of the self, as an assault on individual liberty.

For the theoretically-minded, this strikes as another way to frame debates about agency versus structure, about freedom versus necessity, about which is the more important, the determinant rather than determined. Marxists might recognise such a dialectic as a rerun of debates that raged throughout the sixties and seventies about humanist versus anti-humanist Marxism, about whether subjectivity ought to prevail over objectivity; or whether Marxist history is really objective, a process without a subject, a theory more amenable to the affirmation of collective necessity.

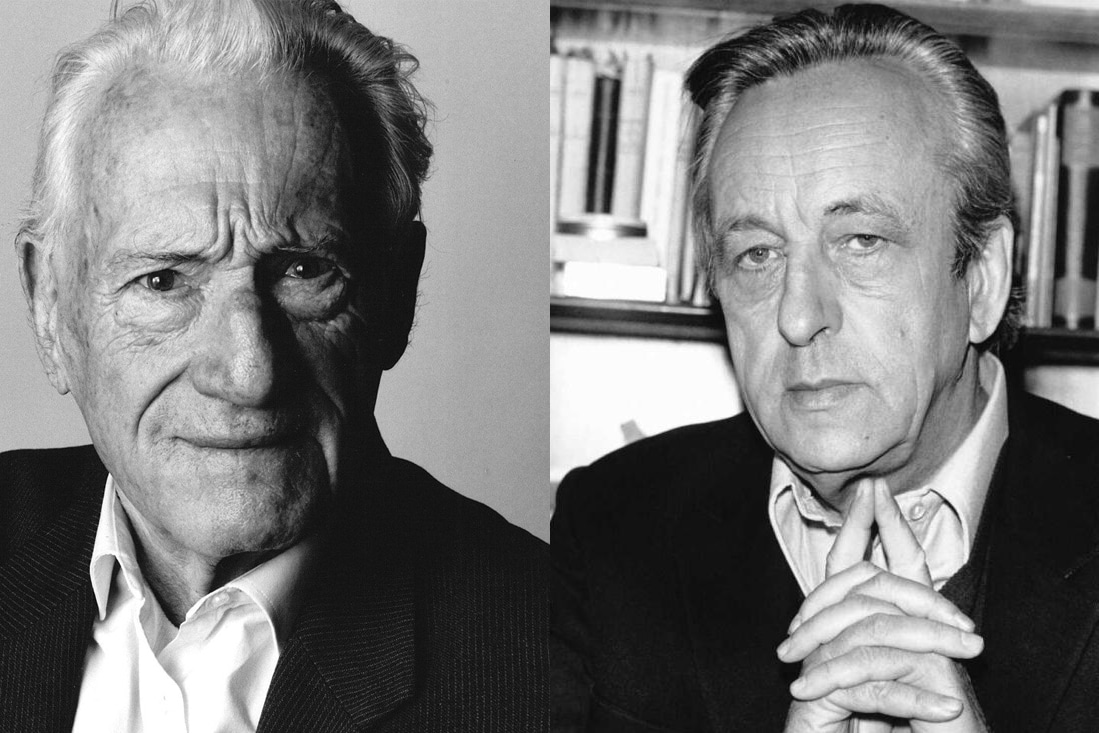

Humanists like Henri Lefebvre (1901-1991) suggest Marxism should celebrate what Hegel called a “freedom of subjectivity,” that it should prioritise the free will aspect of Marx’s vision, his yearning for “an association in which the free development of each is the condition for the free development of all.” The young, romantic Marx’s Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts are particularly dear to the humanist Marxist’s heart. Here, in 1844, still smitten by Hegelian idealism, the concept of alienation dominates—or rather dis-alienation—the transcending of alienation, the freeing of human beings from capitalist enslavement, from wage labour. Marx posits a “total man” as the liberated person, as subject and object finding unity, rediscovering inner human essence, the ability for people to realise a limitless variety of possible individualities.1

For anti-humanists like Louis Althusser (1918-1990) this reasoning rings out bogus, as something ideological, problematic for any socialist ambition. Socialism needs a “scientific” concept, says Althusser. “Humanism” here presupposes an “empiricism of the subject,” a kind of “essence” to human beings, which, Althusser reckons, the mature Marx—the Marx from the mid-1850s onwards—rejects. Humanism throws a “universal” veil over society, whereas revolutionary struggle isn’t a struggle to liberate “humankind” as such, but a struggle between classes. So, if we should ever talk about humanism, says Althusser, we might at least talk about “class humanism,” or “proletarian humanism.” Marxist liberation isn’t about releasing any transcendental human essence, nor expressive of personal freedom; it’s a historical phase that ends class exploitation, that builds democracy for the working classes.2

Humanist Marxists accuse anti-humanists of dogmatism—of endorsing an “official” Marxism, under Stalin’s watch, with its programme of “the dialectics of nature.” Class struggle therein is seen as objective and deterministic, unfolding without conscious human agency, almost behind the backs of real people, like waves eroding the shoreline. Dogmatic Marxists, Lefebvre says, are happy to move people aside, being especially leery of Marx’s early writings. After all, they might give Soviet workers dangerous ideas about alienation in their own society. But if world communism is inevitable, an inexorable act of nature, as Stalin insists, people can be readily expunged from making history; Marxism elides into economism. Everything else—sociology, psychology, speculative philosophy, etc.—is reformist, irredeemably bourgeois.

Anti-humanists reckon the problem with dogmatism is too much humanism, not too little. Humanism encourages “the cult of personality,” says Althusser, the agency accorded to glorious leaders who supposedly make history all by themselves, like Stalin—or Hitler and Mussolini, or like a few of our own contemporary despots. This is divine worship of the individual, subjective humanism sneaking in through the back door, ideologically poisoning the rest of the house. The cult of personality has no place in Marxist theory, Althusser says, which is why he posits the provocative thesis that Marxists should break with the idealist category of “subject.” History has a “motor,” according to Althusser, but no subject. “Individuals aren’t ‘free’ and ‘constitutive’ subjects in the philosophical sense of these terms,” he says. “They work in and through the determinations of the forms of historical existence of the social relations of production and reproduction.” It’s another way of repeating Marx’s oft-cited dictum, that the masses make their own history, but not under circumstances chosen by individuals themselves.

***

Lefebvre and Althusser, as budding opposites, joined the French Communist Party (PCF) as young men. The former, scared by the Great War, in 1925; the latter, inspired by militant Resistants, in 1948. Lefebvre would, for “ideological deviations,” get expelled in 1958, though he’d reembrace the Party in the 1970s; Althusser would never leave, yet remained an outspoken critic. As dissident Party members, Lefebvre’s Marxism bathed in sunlight, was energised by what Ernst Bloch called a utopian “warm stream”; Althusser’s assumed a darker, colder, more melancholy cast. Lefebvre’s sixty-odd books overflow with the loose spontaneity and passion his Marxism advocates; Althusser’s writings, by contrast, are essays, tight and concise, shorn of frills.

Althusser’s anti-humanism insists that Marxism beds itself down in “the concrete analysis of a concrete situation.”3 But Lefebvre’s humanism doesn’t want to give up the ghost—geist—of alienation. If progressives jettison it, he says, won’t the living baby disappear with the stagnant bathwater? And yet, maybe twenty-first-century Marxism needs to loosen alienation from its subjective moorings, where it can degenerate into subjectivism, into an expression of bourgeois individuality and freedom. Maybe we need to see alienation not as undermining some abstract human essence, but posit it concretely, as a historical category, at work and in life. The traits of Marx’s factory system have entered into the generic traits of our society writ large. Life itself nowadays assumes a kind of industrial logic, with speed-ups and intensity drives, drills and efficiency targets, audits and assessments. As workers lean in, as they fill in those leaky non-workday pores, alienation is concrete. It moves with the times and so should we. It takes on meaning in different epochs, changes as we change, as our needs and aspirations change, as they change us, as we change them.

Decades ago, witnessing many German and European workers opt for fascism, vote against their class interests, Lefebvre spoke of alienation as mystified consciousness, recognising how propaganda transformed people’s minds en masse. He never saw this morph into social media, into misinformation and fake news, into twenty-first century estrangement, whose ideological channels never switch off and span the entire planet. Our alienation is different now, more cunning, less evident. And our consciousness is different, too, reshaped and re-mystified by a culture deliberately intent on undermining people’s capacity to think critically, to analyse broadly and deeply. Bombarded with banal messages and commercial stimuli, our brain cells have been pulverised by informational overload. Differentiating truth from falsity becomes increasingly difficult, fertile terrain for cults of personality to prosper, for demagogues to make promises they’ll never keep. But no matter.

Here, Althusser’s analysis still shines light on the murky zones of ideology. Ideology is never just free-floating, says Althusser, never simply (or complexly) a system of ideas innocent in life. Rather, ideology gets “materially” constituted, is embedded in particular capitalist “apparatuses” that manufacture it, that transmit it. They stalk the public, statist sector—in education and law, in the police and army, in religious institutions and political parties—as well as civil society—in business and advertising, on TV and radio, in newspapers, in social media and information technology. In fact, everywhere, we are enveloped in ideology. State ideological apparatuses can act repressively, through force (sending in the police and military), or else engineer compliance via consent, via more subtle modes of domination.

Althusser says ideological apparatuses “interpellate” people, “hail” us as concrete class subjects. It all happens, he says, along the lines of the most commonplace everyday scene—a hailing from across the street: “Hey, you there!” Conscious we’ve done something wrong, we look over, get taken in, believe the caller. Somehow, instinctively, we listen, accept it is us being called. This is how reality takes place through ideology, Althusser says, even if it seems to take place outside of ideology, beyond it. This is how we get “recruited” as class subjects and why Marx says life conditions consciousness—and not the other way around. What Lefebvre calls mystified consciousness, Althusser terms “an imaginary representation of our real conditions of existence.”

Ideology isn’t false consciousness: it’s real, has real anchoring to reality, real material existence. The bluster of Trump or Boris Johnson interpellates large numbers of people because their calls have what Althusser labels “a recognition function,” something a person needs to believe, wants to believe, recognises. It hits a reality buzzer somewhere inside them, becomes the necessary mood music for dissatisfied and alienated people. They want to hear this music, are open to it, feel the need to believe it. It’s on the level of feeling that messages get through, stoke up visceral emotions. Yet recognition functions through illusory representations, through imaginary distortions of actual reality (like the notion the Presidential election was rigged). “Experience shows,” says Althusser, “that the practical telecommunications of hailing is such that they hardly ever miss their man.” Verbal calls, messages popping up on screens, entering inboxes or dropping through mailboxes, getting bawled out at political campaigns, tweeted on social media—“the one hailed always recognises that it is really them who is being hailed.”

Althusser labels the drama of interpellation his “little theoretical theatre,” and the notion of theatre here is suggestive, full of dialectical resonance. Theatre stage plays involving actors with scripts. These actors assume roles and know how to learn their lines. They memorise them, act these lines out in character. Before them lie audiences, gatherings of people looking on, perhaps innocently, perhaps dangerously—dangerously in the sense that they are identifying with the actors. In interpellation, actors and audience become one, get bundled together; you can’t differentiate one from the other—at least in audiences’ heads—because the latter begin to live out the roles they’re watching. They come to the theatre, Althusser says, really to see themselves, and that’s why it’s dangerous: it’s precisely how interpellation hails you in life.

Althusser took a keen interest in theatre. While he plainly sees bourgeois theatre like bourgeois life, as a paradigm of interpellation, laden with ideology, he nonetheless understands theatre as part of the solution, too, as educational for not getting taken in by ideology. In this respect, misrecognition becomes a vital arm of political resistance, something Althusser tries to highlight in his articles on Bertolt Brecht.4 Althusser says Brecht revolutionised bourgeois theatre the same way Marx revolutionised bourgeois philosophy. Marx says philosophy shouldn’t be contemplative and neither should theatre says Brecht.

It shouldn’t be “culinary,” he says, mere entertainment for audiences to drool over the play’s “hero.” In Brechtian “epic” theatre, there are no heroes, not even in plays like The Life of Galileo and Mother Courage, two of Althusser’s favourites. This is “materialist” theatre. There, the masses make history, not heroes. Brecht wants no object of identification—either positive or negative—between spectators and the spectacle, no complicity between the two, no pity or sentimentality, no anger or disgust. It’s the only sort of alienation that kindled Althusser’s political imaginary: the famous “alienation-effect,” Brecht’s Verfremdungeffekt—or V-effekt—the distancing that avoids reifying inter-subjectivity, that counteracts any possible emotional empathy audiences develop with the characters.

Brecht demands cool thinking responses from his audiences, not hot feeling outbursts. He wants to foster critical interpretation, a thought that provokes action. Overthrown are classical ideals of Greek theatre, where the repressed energy of the drama erupts into what Aristotle called catharsis—a stirring emotional release, usually at the play’s finale. It sounds like the din of a Trump rally, its demagogic rage. Brecht wants to snub any fictional triumph, any fear and misery of the Second Term. He interrogates context rather than panders to confabulation. “The public ought to cease to identify with what they’re watching,” says Althusser. “They ought to find a critical position,” take a stand on the outside, not be taken in on the inside. It’s precisely this critical distance that needs to be carried over into real life, into our diseased life. Like with all viruses, prevention is always better than cure.

***

As Althusser drifted away from the PCF in the late 1970s, Lefebvre drifted back into it. The decade pushed and pulled socialists and communists everywhere, ushering in as much a meltdown of the post-war Left as of post-war capitalism. Gramsci might have called this an interregnum, between a dying past and a new era yet to be born, haunted in the meantime by monsters. For awhile, the Left in France called for unity, for a “Union of the Left”; a popular unity to ward off monsters, between the PCF and the Socialist Party (PS), in solidarity with other Left factions and forces—avoiding, on the one side, dogmatism and sectarianism within its own ranks, and striving, on the other, to forge an electoral pact, a ballot box socialism.

The European Left was distancing itself from Moscow, abandoning commitment to “dictatorship of the proletariat,” embracing instead so-called “Eurocommunism”—“the democratic road to socialism.” The workers’ movement needed to fight for structural reforms, transform the capitalist system by stages, eventually altering it wholesale. Head on confrontation between bourgeoisie and proletariat ought to be avoided; socialism without the consensus of a large majority of the “progressive” population would be impossible. Rather than take the enemy’s fortress by assault, in one fell swoop, Eurocommunists needed to encircle this fortress, undermine it gradually, vote it out, erode its power. Later on, they could seize control, democratise the state.

Althusser thought this a grave tactical error, a betrayal of the working classes, and said so after the Union’s electoral defeat in 1978; Lefebvre seemed more open, more curious about its exploration, more ready to face reality. Althusser wrote a series of blistering articles in April, 1978, serialised in the newspaper Le monde, about why he thought the Left union had collapsed and “What Must Change in the Party.”5 He said the Party had to step out of its own “fortress,” embrace the popular movement, have more faith in the rank and file. “Democratic centralism” could only work, Althusser said, if the PCF loosened its absolutist grip on the workers’ movement. Party bigwigs, alas, had been more concerned with defending their institutional privileges against the PS than in allying to combat a national bourgeoisie.

Lefebvre also released a text in 1978—a crucial year in the demise of European Left—a book with a revealing title: La révolution n’est plus ce qu’elle était [The Revolution Isn’t What it Was], a dialogical exchange with Catherine Regulier, Lefebvre’s newly-wed and young PCF militant. Althusser is frequently pilloried by Lefebvre; Regulier usually sides with her Party comrade in opposition to her husband, making the conversation particularly fascinating because of its tangled loyalties. Like Althusser, Lefebvre disagrees with Gramsci: the Party isn’t a Modern Prince; Stalin put paid to such imagery. Yet rather than orchestrate “democratic centralism,” Lefebvre wants to develop and generalise “autogestion,” a worker self-management, pushing the Party to accept more decentralisation; power needed devolving to local communes; more coordinated direct action required fostering at ground level. Lefebvre, in effect, sought a democratic line between Party and state, wishing both would wither away.

Étienne Balibar, a former student and confidant of Althusser, and co-author with his teacher of Reading Capital, told me via email that Lefebvre and Althusser actually encountered each other during this fraught period. They met along with other Marxist theoreticians (like Christine Buci-Glucksmann and Jean-Marie Vincent) at Lefebvre’s apartment on rue Rambuteau (overlooking the Pompidou Centre). Balibar says they were “private meetings” [réunions privées], organised by another ex-Althusser student Nicos Poulantzas, whose idea was “to try and reunite Marxist intellectuals and relaunch, if possible, Leftist debate and the Union of the Left in distress [L’Union de la gauche en perdition].”6

“Lefebvre was old,” recalls Balibar, “but very alert and a charming conversationalist.” He wanted the Left “to bury the old hatchets,” to overcome its internal differences and disagreements, have everyone make peace with one another. Maybe he was recalling what Lenin said about Marxists and anarchists? That there was nine-tenths similarity and one-tenth difference. Didn’t the same go for humanists and anti-humanists? “Althusser was often ill and absent in those days,” Balibar remembers. “He came a few times to the meetings without saying much, sometimes saying nothing at all.” “Lefebvre,” says Balibar, “told me that the Presses Universitaires de France had commissioned him to do a book on ‘Marx Today’. ‘Why don’t we do it together?’ he asked me. Like an idiot I refused, under the pretext that the deadline was too short for me, and that I write much slower than he does. To this day, I regret not doing it.”7

Lefebvre’s and Althusser’s work over that decade, from differing perspectives, tried to valorise for the Left a capitalist state in crisis. Could a unified Left leverage state power away from a disgruntled Right? Could it do so in the streets, in the factories, and through the ballot box? Could forces within the state be modified by organised pressure from the outside? Could pressure from the outside not only transform the inside but actually become that inside? “On s’engage,” Althusser used to say, “et puis on voit.” And yet, after engaging, after jumping into the fray, what one saw was a dramatic power shift, a transition and renewal in the reverse direction. It was the Right who got its act together, who closed ranks, whose class power “condensed,” just as the Left’s fell apart, as its unity fractured into disunity.

By the mid-1980s, a lot of ideas about popular unity and democratising the state, about Eurocommunism triumphing, collapsed, got rejected—almost before the votes were cast. Somehow its programme had overly compromised; or else hadn’t compromised enough. It was as if the Left didn’t know whether it was coming or going, having no more legs to stand on. It had kicked away both the Party and the People, hobbled lame. Still, unlike Britain and the US, “the Left” did nonetheless triumph in France, in 1981, under François Mitterrand’s Socialist Party; yet victory soon turned Pyrrhic, as its “leftist” policies began drawing straight from the Right’s playbook. By then, too, in a gentrifying Paris, an octogenarian Lefebvre had been evicted from his rental on rue Rambuteau and a depressed Althusser had strangled his beloved wife, Hélène, in a moment of “temporary insanity,” ending his days as a public figure. Poulantzas, meanwhile, had freaked out at a friend’s apartment, throwing himself out of the window in an impulsive suicidal defenestration.

Suddenly, the “New Right” set off on its long march, telling us there is no such thing as society anymore, only individuals and families. From struggling to ensure a providential state, now there was apparently no more state, not a public state for people anyway, only one preparing the political terrain for free market entrepreneurialism. Thus arose an awkward predicament for progressive people, especially for Marxist theoreticians: those items of “collective consumption” so vital for reproduction of the relations of production, so indispensable for propping up demand in the economy and for satisfying working class needs—public housing and infrastructure, hospitals and collectively consumed goods and services—were getting cast aside. How could this be? What once appeared essential ingredients for capitalism’s continued reproduction, for its long term survival, now turned out to be only contingent after all.

The Left has never really come to terms with a seismic tremor that registered big digits on the neoliberal Richter Scale. The 1980s bid adieu to social democratic reformism, to an age when the public sector was the solution to capitalism’s woes and the private sector the problem. Henceforth the former needed negating, Right ideologues argued; the private sector was the solution and a shot and bloated public sector the problem. State bureaucrats dishing out items of collective consumption through some principle of redistributive justice gave way to reality in which the market ruled. Writ large was the beginning of the privatisation of everything, of an ideology of possessive individualism. “Freedom” became its tagline: free markets, free trade, free choice, freedom to consume, freedom to do one’s own thing, freedom not to care about other people’s freedom.

Successive generations have been force-fed this ideology of freedom, treating anything public, any realm of necessity, with suspicion, as shoddy and inefficient, as something symbolising unfreedom. Now, it’s no longer an ideological category: it’s embedded in people’s brains, a belief system that teaches us how to forget, how to turn our backs on the public realm and ergo on any social contract. Maybe for good reason: the public state has been hollowed out to such a degree that it is shoddy. Its core functions—the planning and organisation of public services—have been outsourced to private consultants and contractors who’ve delivered little yet raked in much.

And as pandemic raged, countries who’d hollowed out their states most of all fast discovered they had neither the hardware capacity nor the software know-how to deal with a massive societal problem. So they doled out millions to private consultant “experts” like McKinsey who apparently did. When, in Britain, the latter instigated a National Health Service (NHS) test and trace system that hardly worked, we realised these “experts,” too, were clueless. COVID-19 has exposed the shortcomings of the privatised state, of the incompetence of private enterprise addressing public health—and of how public health challenges aren’t resolvable by individuals and families alone.

There’s plenty of collective necessity, of course, dealing with a global pandemic. But collective necessity can only work if people recognise the state as “democratic,” know good government from bad. These days, in populist nations, democracy seems like a vision from another planet. We might call these uncivil states because people there have lost their sense of duty to one another. We’ve been kidded by demagogues into thinking we’re all free agents capable of doing what we like, and if we can’t then it’s someone else’s fault. The European Union’s? Big government’s? Rarely big business’s. Private inclinations have run roughshod over public interests, cults of personality have gone viral. Maybe intelligent people, inspired by some Brechtian V-effekt, might one day acknowledge society again, might distance themselves from ruling class lures and lies. Perhaps then we’ll see how we can be freer if each of us admits that we are part of a public culture in desperate need of collective repair, that the goal of socialist democracy is to fight to reclaim public power.

En route, we might also remember Marx, who insisted that real freedom came though addressing necessity. “Freedom can only consist in socialised man,” Marx said, “when associated producers rationally regulate their metabolism with Nature.” “A shortening of working day is the basic prerequisite for freedom,” he thought. Life blossoms forth on such a basis, he said. Freedom without necessity is yet more bourgeois claptrap, another ideological ruse to perpetuate its class dominance. “The bourgeoisie lives in the ideology of freedom,” Althusser tell us, and makes us live in it, too, forces its concept down our throats. But real freedom is hard when you have to worry about making the next rent check, when you wonder if your job will be there tomorrow, or what happens if you get sick. Free choice means practically nothing when you’re financially enslaved. Freedom here isn’t very humanist. Indeed, when it comes to anti-humanism, capitalism has got Marxism licked any day.

Notes

- ↩ See, especially, Dialectical Materialism (1939), Lefebvre’s humanist rejoinder to Stalin’s Historical and Dialectical Materialism, published in Moscow a year earlier.

- ↩ See Althusser’s For Marx (1965), the best introduction to his anti-humanist Marxism.

- ↩ We might remember that even Marx’s abstract reasoning is concrete. Marx is weary of abstract abstractions, calling them in the Grundrisse “chaotic conceptions.” In a way, Marx would have been sceptical of epidemiologists’ scale of “population.” “Population,” Marx says, is an abstract abstraction, “if I leave out the classes of which it is composed. These classes in turn are an empty phrase if I am not familiar with the elements on which they rest. E.g. wage labour, capital, etc. These latter presuppose exchange, division of labour, prices, etc.” When we follow Marx’s concrete logic, we can see more clearly how the COVID pandemic doesn’t just affect the population, but strikes different populations, strikes them unevenly and unequally, subject to positioning in the wage-relation and division of labour. Here we might add different races, too, and different classes of those races.

- ↩ Two instances are “The Piccolo Teatro,” a discussion of Bertolazzi alongside Brecht, which Althusser included in For Marx; and another, “Sur Brecht et Marx,” in Écrits philosophiques et politiques — tome II (1997).

- ↩ New Left Review translated and republished Althusser’s missives as a standalone essay (see NLR, No.109, May-June 1978).

- ↩ Even if little of practicality emerged from these meetings, protagonists did help pioneer a very interesting, if short-lived, theoretical journal called Dialectiques; between 1973 and 1981, 33 issues appeared, full of wonderful material that still inspires. Both Lefebvre and Althusser feature within its now-yellowing leaves, yin and yang opposites of a truly dialectical Marxism for what were truly dialectical times.

- ↩ Ironically, the book, Être Marxiste Aujourd’hui [To be a Marxist Today], would only materialise years later, in 1986, co-written with Patrick Tort, a strange homage to Georg Lukács. The focus was a conference at Paris’s Hungarian Institute from 1955, celebrating Lukács’s 70th birthday, an opportunity for Lefebvre to critique as well as champion his old Hegelian-Marxist colleague. If Balibar regrets passing up on joint-authorship, we can only regret not reading what might have been.