In Latin America, coups d’état are always underway. When a government goes beyond being merely procedurally democratic and advances towards social justice, the always latent coup mechanisms are accelerated. The tensions that lead to hard or soft blows revolve around three main factors: mobilized peoples, local violent oligarchies within the country that are submissive to Washington and, the limit of what the United States is willing to tolerate in each country.

More than 34 coups d’état have been carried out in 12 Latin American countries since the second half of the twentieth century. Most have been consummated, and only a few have failed in the face of popular resistance or the skill of the governments in power. The interests of the United States in the region and the disputes between oligarchies and mobilized societies are triggers for a series of processes that are permanently activated and reactivated.

Political scientists, internationalists and Latin America specialists consulted by Contralínea magazine agree that, to begin with, in Latin America coups d’état are only carried out against leftist or progressive governments. And also, in a generalized way, the right-wing in the region is always prone to request, promote, support or sustain coup attempts when the privileges of the oligarchies are threatened.

Consequently, right-wing oppositions to progressive governments in Latin America ”are not normal oppositions,” that is, they do not conform to what is expected of an opposition within the conventional definitions of the democratic political system.

A democracy that transcends the merely procedural forms and encourages the inclusion of the broad, historically neglected sectors “will not be faced with a normal opposition; it will not have an opposition that follows the norms of the rule of law as would be expected in a political science book.”

This dire warning comes from Silvina Romano who holds a PhD in political science from the Center for Advanced Studies of the National University of Córdova, Argentina. Romano adds that any government that tries to alter the structure of society and advances towards the economic, political, social and cultural inclusion of the majorities always have to face the reaction of an oligarchy that does not respect the rules and that acts outside the institutional framework, although that oligarchy might say that it is ”respectful” of the institutions.

This dire warning comes from Silvina Romano who holds a PhD in political science from the Center for Advanced Studies of the National University of Córdova, Argentina. Romano adds that any government that tries to alter the structure of society and advances towards the economic, political, social and cultural inclusion of the majorities always have to face the reaction of an oligarchy that does not respect the rules and that acts outside the institutional framework, although that oligarchy might say that it is ”respectful” of the institutions.

Romano, who also holds a joint post-doctorate from the National Autonomous University of Mexico’s (UNAM) Center for Research on Latin America and the Caribbean, and the Center for Research and Studies on Culture and Society from the National Council for Technical and Scientific Research (CONICET) of Argentina, gives as an example the recent events in Bolivia, Ecuador and Argentina, countries that sought to create a new institutional framework of social justice and that, due to this very reason, exacerbated the historical tensions in their respective societies. Romano now identifies Mexico’s current Andrés Manuel López Obrador administration and the National Regeneration Movement party (MORENA) as a similar case.

Romano clarifies that this type of processes are not reduced to a dispute between the government and the right-wing opposition. The confrontation also occurs within the governments themselves, because the institutions are not renewed overnight. A part of those who make up the progressive governments themselves maintain links with the elites. This is something that is impossible to avoid because institutions cannot be renewed simply by firing all those who were already part of them and appointing new members. So, within the governments themselves ”there is a push and pull when wanting to move forward.”

Romano, who is also researcher and coordinator for the United States and Latin America Analysis Unit of the Latin American Strategic Geopolitics Center (CELAG), also points out that opposition to progressive Latin American governments from the United States is a constant factor. From there, it operates through political actors, the media, and organizations such as the United States Agency for International Development (USAID).

The attacks coming from the U.S. exploit the internal problems experienced by progressive governments in Latin America and magnify their mistakes. The irony is that the complicated situations that the nations may face are results of U.S. policies.

Jorge Retana Yarto, who is the first director of the School of Intelligence for National Security (ESISEN) of the current Mexican government, warns that when the United States decides to weaken and overthrow governments, the job is given to its intelligence agencies, both those that operate from with the U.S. territory and those that function abroad.

The manuals that the agencies and their allies follow are well known. And the script for a coup has been followed in at least a dozen Latin American countries since the second half of the twentieth century, most with success, only a few have been thwarted halfway. The implementation of the coups, both hard and soft, has been observed in several countries including Chile, Guatemala, Brazil, Argentina, Paraguay, Uruguay, Venezuela, Honduras, Ecuador, Bolivia, Dominican Republic, and Panama. In several of those countries, on more than one occasion.

Romano takes the example of the ongoing coup campaign against Mexico. Due to the violence that was generated by the so-called ”war on drugs” and the militariization of its borders, suddenly, all responsibility for this is blamed on the current government, affirms Romano. And those in the United States who are launching a condemnation narrative seem to ”forget the 13 years of the Mérida Initiative, in which the entire security forces were organized not only in regard to the drug trafficking agenda, but also to migration.”

Romano takes the example of the ongoing coup campaign against Mexico. Due to the violence that was generated by the so-called ”war on drugs” and the militariization of its borders, suddenly, all responsibility for this is blamed on the current government, affirms Romano. And those in the United States who are launching a condemnation narrative seem to ”forget the 13 years of the Mérida Initiative, in which the entire security forces were organized not only in regard to the drug trafficking agenda, but also to migration.”

The United States plan for Mexico and Central America has not only been reduced to the impulse of the free market, Romano explains. A substantial part has been the militarization of companies. To do this, it has used a supposed war against drug trafficking that has only generated more drug trafficking, violence and rupture of the social fabric.

Romano’s experience in researching the relations between the United States and Latin America and criticizing development assistance, lead her to conclude that the government of Joseph Biden is reconfiguring policy towards the region by maintaining the presence of the Southern Command of its Armed Forces (SOUTHCOM) and of agencies such as the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) and the Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA), the latter, especially through training programs for the region.

What is new about the Biden administration is that it is trying to ”make a kind of mutation of the anti-narcotics strategy to an anti-corruption war: it is going to operate from a façade of apparent soft power using hard power.”

The fight against corruption in Latin America, as is conceived in the United States, implies vigilance of the governments of the region, as well as the establishment of institutions that guarantee loyalty to U.S. democracy, which is valued more highly than equity and social justice.

“How are you going to create a healthy, less corrupt institution, if you have more than half the country in poverty?” asks Romano.

What kind of justice is that? It is a notion of justice tied to certain procedural structures that in theoretical terms are very interesting; but applied in societies where corruption is the consequence of years of misery, marginalization and violence.

Silvina Romano, who is also a specialist in underdevelopment and dependency in Latin America, explains that the great problem for Latin American countries is precisely the dependency relationships established with the United States over centuries. It has only managed to generate export-oriented economies and maquiladoras that do not have any kind of projection on the society or possibilities for social development.

In his role as economist, professor of finance and intelligence specialist for national security, Jorge Retana Yarto points out that the smear and weakening campaigns against progressive governments in Latin America never show up in isolation. They are accompanied by other equally important elements.

In his role as economist, professor of finance and intelligence specialist for national security, Jorge Retana Yarto points out that the smear and weakening campaigns against progressive governments in Latin America never show up in isolation. They are accompanied by other equally important elements.

In the coups that have taken place in the region, economic sabotage has been fundamental. In Chile, for example, after the triumph of Salvador Allende, paper money was falsified to throw the economy into chaos. At the same time, capital was withdrawn from the country and pressure was maintained on the Chilean peso in order to devalue it.

More recently, in the case of the attempted soft coup against Cristina Kirchner in Argentina, a systematic attack on the Argentinian currency was maintained and a U.S. court ordered Argentina to pay debt under disadvantageous conditions. The barrage came not only from abroad but also from within the country, explains Retana Yarto.

Romano considers that the López Obrador government seems to have a clear understanding of this situation, but it is impossible at the moment for it to dissociate from the economic relationship of subordination it has with the United States or from the immigration policy imposed from that country.

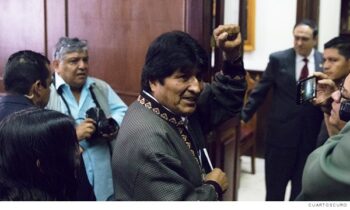

Yes, there seems to be advances in the new relationship between Mexico and the south of the Continent of the Americas. ”The Mexican government now openly says: ‘We are Latin America,’” asserts Romano, and demonstrates as examples the role that the Mexican government adopted in the face of the coup d’état against Evo Morales of Bolivia, and the agreements that it is sealing with Argentina and the ones it intends have with Cuba in near future.

“Mexico is a great country of Latin America,” states Romano.

Knowing the history of Latin America, Mexico could be at the helm.

John Saxe-Fernández, PhD in Latin American Studies, points out that the arrival of López Obrador to the Mexican presidency was seen with hope throughout the continent.

John Saxe-Fernández, PhD in Latin American Studies, points out that the arrival of López Obrador to the Mexican presidency was seen with hope throughout the continent.

A great sigh of relief was felt in Latin America with the arrival of a government that began by articulating the national public interest of Mexico.

Saxe-Fernández is a national researcher emeritus for the National System of Researchers of the National Council of Science and Technology (CONACYT). Saxe-Fernández states that already ”there are links that are connecting” Mexico with other Latin American countries. ”There is a process of multilateralization of economic, political and cultural relations,” but it is progressing slowly.

Mexico needs an even more active diplomacy than the one that is being carried out. We need more strength, more relationship, more multipolarization.

Saxe-Fernández is also professor at the Faculty of Political and Social Sciences at UNAM and a researcher with the Center for Interdisciplinary Research in Sciences and Humanities of the same university. He alerts that Mexico has to deal with a 36-year legacy of neoliberal governments—“a drowning in the United States.” He points out that it will not be easy to get rid of the economic treaty it signed with the North American nations.

Now the USMCA [United States, Mexico and Canada Free Trade Agreement] have become law because of its status as a treaty. It is a brutal legacy that we have.

With the treaty, Saxe-Fernández continues, the United States bought Mexico’s accumulation sectors: Petróleos Mexicanos (PEMEX) and the Federal Electricity Commission (CFE). For this reason, the “structural reforms” of the past 2 six-year terms and the current dispute generated by the present government trying to chart a different course for the two productive companies belonging to the Mexican State, have led to “very serious problems” for the country.

With the treaty, Saxe-Fernández continues, the United States bought Mexico’s accumulation sectors: Petróleos Mexicanos (PEMEX) and the Federal Electricity Commission (CFE). For this reason, the “structural reforms” of the past 2 six-year terms and the current dispute generated by the present government trying to chart a different course for the two productive companies belonging to the Mexican State, have led to “very serious problems” for the country.

The United States, the orchestrator

That Latin America is historically the scene of coups d’état has to do, first of all, with the fact that there exist mobilized societies in the continent. Progressive governments do not come out of nowhere. Behind all progressive governments there is a large number of people demanding justice. This is precisely why progressive governments come, explains Silvina Romano.

John Saxe-Fernández agrees. As the author of 23 books, including, La compraventa de México [Mexico Sold and Bought] (Plaza and Janés 2002, 2006) and Terror e Imperio [Terror and Empire](Random House 2006), Saxe-Fernandez states that in the region there is always “a popular demand for social justice, health, education and the right to food. Latin America is the region with the greatest polarization in the world.”

Romano explains that the dependence of the nations of the region is not the result of submissive societies. On the contrary, there are peoples in constant mobilization in the struggle for social justice.

The submission is clearly that of the elites, Romano adds. These are the dominant groups at the internal level, but they are dependent and submissive to the countries of the center—the United States and Canada; these are elites who hold no bargaining power. ”The submission comes from them.” These elites live in Latin America, pay few taxes and it is “easy for them to articulate themselves with the powers that be from abroad;” the powers of the United States, with whom these elites have had institutional, personal, and social networks and family ties for decades.

Saxe-Fernández points out that coups d’état accelerate when projects that deviate to a greater or lesser extent from U.S. hegemony begin to be successful and can be considered as examples for other countries to follow. It is then that ”a series of measures are articulated from within and from without” against progressive governments. It is a well-known fact that the United States is always involved, directly or indirectly.

Saxe-Fernández, who is also a teacher at Washington University, agrees that, due to its proximity to the region, the United States is always a factor present in any coup in Latin America:

We have that historical burden of the effects of U.S. expansionism and formation of class structures in Latin America.

Romano remarks that perpetrators do not always go as far as the coup itself, soft or hard. The coup is set in motion and probably, before it is consummated, the progressive government is controlled or forced to ”rectify.” Economic sanctions are not uncommon, but other, less drastic mechanisms have been systematically applied with proven success.

“Along with economic pressure there is political, diplomatic and media pressure,” adds Romano.

“Along with economic pressure there is political, diplomatic and media pressure,” adds Romano.

They operate through an institutional network that has been forged since the Cold War. Organizations such as the DEA have links with ‘expert voices’ which, in turn, have links with very important media in the United States that have their counterparts in Latin America.

Depending on the situation in each country, this institutional network can be successful almost immediately in generating consensus around certain governments. Romano clarifies that the media do not act or do anything alone. And instead of blows, the media exert attrition strategies.

However, this political destabilization is accompanied by another strategy of an economic nature. ”Our countries are tied to loans and investments that arrive to our financial centers.” For this reason, for example, in Mexico, it would not be necessary to ”take the Zócalo” to delegitimize its government.

Furthermore, of all the countries in the region, Mexico is the country where it would be least necessary to strike a hard blow.

Romano states that “Mexico is considered part of the United States territory now. There is no need to carry out a coup when the United States agencies are the ones that have a say in what must be taught in the study programs in the law schools of Mexico, for example.” In political and even constitutional terms, United States agencies have occupied Mexico through certain institutions.

Romano states that “Mexico is considered part of the United States territory now. There is no need to carry out a coup when the United States agencies are the ones that have a say in what must be taught in the study programs in the law schools of Mexico, for example.” In political and even constitutional terms, United States agencies have occupied Mexico through certain institutions.

“I cannot imagine the Department of Defense with a covert operation against Mexico, because it is not necessary,” concludes Romano.

That is the saddest thing. What we do get instead is the Mexican right-wing asking for help from certain agencies to destabilize the López Obrador government. That has been part of the soft coup in Latin America. There are declassified documents of businessmen who travel to the United States to ask for help.

There remains a question to be asked: the United States would not easily support a coup in Mexico; but is there a limit that it is not willing to tolerate and that could make it consider that a coup should be carried out?

”Yes, the nationalization of resources,” Romero replies immediately. That is the fine line: energy, oil, land and tariffs, that is what the United States would not be able to tolerate.

Saxe-Fernández considers that in Mexico there is an opposition ready to do whatever it takes to oust López Obrador from power. In fact, it had already been operating before Obrador came to the presidency. That USAID finances the political-business group that opposes the current Mexican government is not by chance. “I don’t expect anything good from those people,” concludes Saxe-Fernandez.

To receive money from USAID is to play the game by the rulebook of the United States, something that we have seen consistently in the Latin American right-wing.

A selection of coups d’état, soft and hard, in Latin America:

| Year | Country | Event |

| 1954 | Paraguay | Coup against President Federico Chávez by the armed forces. Dictator Alfredo Stroessner assumes power. |

| 1954 | Guatemala | CIA participation in Carlos Castillo’s coup against Jacobo Árbenz confirmed |

| 1955 | Argentina | Eduardo Lonardi leads the overthrow of Juan Domingo Perón |

| 1956 | Honduras | A Military Junta assumes power |

| 1958 | Venezuela | Wolfang Larrazábal leads overthrow of Marcos Pérez Jiménez |

| 1960 | El Salvador | José María Lemus is removed from power |

| 1962 | Argentina | José María Guido removes Arturo Fondizi from power |

| 1962 | Peru | Ricardo Pérez Godoy overthrows Manuel Prado Ugarteche |

| 1963 | Honduras | Coup against Tamón Villeda Morales |

| 1963 | Dominican Republic | Miguel Atila Luna and others lead coup against Juan Bosch to install a Triumvirate |

| 1963 | Ecuador | Military Junta overthrows Carlos Julio Arosemena Monroy |

| 1964 | Brazil | Humberto de Alencar leads a coup against João Goulart. Military dictatorship begins. |

| 1966 | Argentina | Juan Carlos Onganía leads the overthrow of Arturo Umberto Illia |

| 1968 | Peru | Juan Velasco Alvarado leads coup against Fernando Belaúnde Terry |

| 1968 | Panama | Boris Martínez leads the overthrow of Arnulfo Arias. Military Junta assumes power. |

| 1972 | El Salvador | Failed coup attempt against Fidel Sánchez Hernández |

| 1972 | Ecuador | Failed coup attempt by armed forces against José María Velasco Ibarra |

| 1973 | Uruguay | Juan María Bordaberry leads coup against the General Assembly. |

| 1973 | Chile | The CIA and the armed forces carry out a coup against Salvador Allende. Augusto Pinochet’s military dictatorship begins. |

| 1975 | Peru | Francisco Morales leads coup against Juan Velasco Alvarado |

| 1975 | Ecuador | Raúl González Alvear leads failed coup attempt against Guillermo Rodríguez Lara |

| 1975 | Argentina | Jesús Cappeli leads failed coup against María Estela Martínez de Perón |

| 1976 | Argentina | Jorge Rafael Videla consummates a blow against María Estela Martínez de Perón |

| 1979 | El Salvador | Carlos Humberto Romero executes coup through electoral fraud, with the support of the military |

| 1980 | Bolivia | Coup d’etat to disqualify electoral results |

| 1989 | Paraguay | Andrés Rodríguez Pedotti leads coup against Alfredo Stressner |

| 1992 | Peru | Alberto Fujimori and the armed forces execute coup against the Congress, dictator Fujimori assumes power. |

| 2002 | Venezuela | Pedro Carmona leads failed coup against Hugo Chávez |

| 2008 | Bolivia | Opposition parties execute failed coup against Evo Morales Ayma |

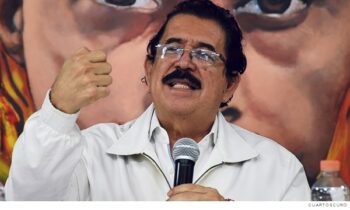

| 2009 | Honduras | Opposition parties and the CIA execute coup against Manuel Zelaya |

| 2010 | Ecuador | National Police and opposition parties execute failed coup against Rafael Correa |

| 2014 | Argentina | Financial organizations and opposition parties execute failed coup against Cristina Fernández de Kirchner |

| 2016 | Brazil | Senate and Judiciary execute coup against Dilma Rousseff |

| 2019 | Bolivia | Armed Forces and opposition parties carry out coup against Evo Morales Ayma |

Translation by Orinoco Tribune