Harry Hopkins and Hallie Flanagan

In the lobby of the Experimental Theater, New York City, 1936. Courtesy, NARA.

A brief but spectacular achievement, the New Deal’s Federal Theatre Project (FTP) (1936-1939) provided jobs for some 13,000 destitute people at its height and created and produced 63,600 performances of 1,200 major theatrical works. It reached audiences of more than 30 million people in cities, towns, and rural areas nationwide, the vast majority of whom had never experienced live theater. With unemployment in the arts cutting deeper than in other hard-hit industries, the New Deal approach to unemployment among theatre people takes on new relevance.

The U.S. Congress funded the Federal Theatre Project primarily to provide jobs for unemployed theatre people during the Great Depression. But WPA administrator Harry Hopkins and the FTP’s dynamic director Hallie Flanagan had a much broader mission: to create a publicly funded national theater, accessible to all, that would both entertain and strengthen public dialogue and democracy.

Flanagan had achieved noteworthy results as director of Vassar College’s Experimental Theater, largely with amateurs and low cost. Along with her wide knowledge of the theatre, including European dramatic experiments, she was well prepared for the challenges of founding a national theater.

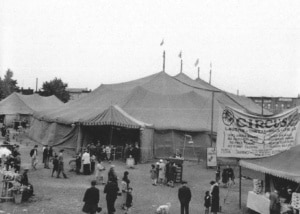

Federal Theatre Circus

New York City, probably 1936. Courtesy, Coast to Coast: The Federal Theatre Project, 1935-1939, Library of Congress.

But the task was daunting—meeting the primary goal of employing jobless theatre people and at the same time achieving quality productions, surmounting funding and bureaucratic hurdles, and responding to union demands while striving for her own broader artistic vision and social goals that evoked criticism and even charges of subversion.

Ninety percent of those employed by the FTP came from the relief rolls. Though several future stars got their start with the FTP, it was not easy to hire top talent. It could be more time-consuming to determine eligibility for an FT hire than a construction worker. Plus, there was the need to hold auditions.

The FTP still stands out for an enlightened racial policy that differed significantly from other New Deal programs. African Americans received equal pay for equal work in every aspect of theatrical production. Audiences were integrated. If a theatre refused to seat Blacks and whites together, the Federal Theatre canceled the performance. Moreover, some of the plays dramatized African Americans’ resistance to white oppression, previously unheard of in American theater.

Witches’ scene from Voodoo Macbeth

Adapted by Orson Welles, New York City, 1936. Courtesy, Library of Congress.

According to Rosetta LeNoire, who acted in one of the Negro Units,

It was the Federal Theatre that gave us so many of our great actors because they were permitted to play roles that they would never have been offered on Broadway.

The repertoire of the Federal Theatre and its national scope are astounding. Productions ranged from circuses, puppet shows, children’s plays and vaudeville to classic works—both traditional and reinterpreted, such as “Voodoo Macbeth,” set in Haiti with the witches invoking voodoo to conjure up their “toil and trouble,” and “Swing Mikado,” set on a Pacific South Sea island, instead of Japan.

There were also modern dramas unlikely to play commercially, such as T.S Eliot’s “Murder in the Cathedral” and the staging of Sinclair Lewis’s anti-fascist novel, “It Can’t Happen Here.”

It Can’t Happen Here.

By Sinclair Lewis, Jewish Theatre Unit production, 1935. Courtesy, Federal Theatre Project, FDR Library.

The Lewis play opened in 21 theatres in 17 states and was performed in English, Spanish and Yiddish—a significant step toward Flanagan’s goal of a national theatre reflecting the ethnic diversity of the country.

The FTP also found creative ways to take theatre to new audiences. New York City’s Caravan Theatre used tractors to tow collapsible trailers storing costumes, props, and stages for outdoor performances at parks, baseball fields, and blocked-off streets.

The FTP’s accomplishments extended to experimental theater. “The Living Newspaper” dramatized current events using newsreels, still photographs, live actors, music, and song. Playwright Arthur Miller, who joined the Federal Theatre as a jobless college graduate, considered “The Living Newspaper” “the one big invention of the theatre in our time.”

Living Newspaper, One-Third of a Nation

Depicting a tenement fire, New York City, 1938. Directed by Arthur Arent, setting by Howard Bay, costumes by Rhoda Rammelkamp. Courtesy, Coast to Coast: The Federal Theatre Project, 1935-1939, Library of Congress.

Despite scrupulous adherence to the facts and even canceling some of the more “hysterical” productions, the FTP came under investigation by the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC). HUAC charged that the plays were “propaganda for Communism.” Flanagan countered that they were “propaganda for Democracy.”

As HUAC’s attack on the FTP and the consequent defunding of the theater show, government support for a national theater likely would be as problematic today as it was then. Some large, public-spirited foundations would need to sponsor such a revival. Surely, factual and dramatic presentations of current events—like the Living Newspaper– could counter the ubiquitous sensational lies to which the American public is routinely subjected. As recent tragic events demonstrate, Americans are no less in need of “propaganda for Democracy” than during the Great Depression.

Federal Theatre Director Flanagan stars–not only as a revolutionary force in the American theatre–but as one who recognized the role of art and culture in strengthening democracy and the national character. Under Flanagan’s leadership, the Federal Theatre was such a force—albeit for too short a time.

Swing Mikado

Directed by Harry Minturn. Courtesy, Coast to Coast: The Federal Theatre Project 1935-1939, Library of Congress.

New Deal government job creation is the model for achieving a current federal Job Guarantee or useful, living-wage employment for all. It is a model for employing jobless people and at the same time building the nation’s physical, environmental, social, and cultural resources. The Federal Theatre is proof that both goals can be successfully achieved. How about a New Deal model to revive the post-pandemic American theatre.?

Collins and Goldberg are co-founders of the National Jobs for All Coalition. Their article is condensed from a piece to be published in an e-book series, E-Theatrum Mundi, ed. by Emeline Jouve and Géraldine Prévot, Sorbonne University Press, 2022.

Sheila Collins, is Professor Emeritus of Political Science at William Paterson University has written and lectured widely on the New Deal and the arts. She is author of numerous books and articles on American politics and public policy, social movements, and religion. She is co-author with Gertrude Goldberg of When Government Helped: Learning from the Successes and Failures of the New Deal, Oxford University Press. She was the recipient of the Albert Nelson Marquis Lifetime Achievement Award in 2019.

Trudy Goldberg, Professor Emeritus of Social Work at Adelphi University led the team of scholars that published the first cross-national study of the feminization of poverty. She has written and lectured on full employment, women’s poverty, the New Deal and social reform movements. Chair of the National Jobs for All Network, she received the Columbia University Seminars 2018 Tannenbaum-Warner Award for Distinguished Scholarship.