Although my Ph.D. advisor Richard Lewontin—known to everyone as “Dick” and to his students as “The Boss”—hadn’t been well lately and wasn’t receiving visitors, the news of his death yesterday at 92 was still a shock. He was without a doubt the most important figure in my career as an evolutionary geneticist, helping form me in both academic and behavioral ways. I can’t imagine a better advisor, and I loved the man. I can offer only a few words in memoriam, and please forgive me if this is the only post I put up today.

Dick’s death in Cambridge, Massachusetts came only three days after that of his beloved wife, Mary Jane (below, left). They were the closest couple I knew. They had been high-school sweethearts and I believe got married when they were around 20. They were inseparable until their deaths. Dick went home to have lunch with her every day, and they read literature to each other in bed each night. Their pet names for each other were “Mr. and Mrs. Bloom”, after Joyce’s characters. To those who knew both of them, it was inconceivable that either could live without the other. It was thus a mercy that neither had to do that that for more than a few days.

As a grad student, I once encountered Dick and Mary Jane when my partner and I were going to the movies at the Harvard Square Theater. We chatted in line, and then Dick said, “Excuse us if we don’t sit with you, but Mary Jane and I like to sit in the balcony and hold hands.” He was not making that up.

It’s hard to think that when I first met Dick, in 1971 at the University of Chicago, where I was accepted to be his student, he was only 42. I was thereafter drafted as a conscientious objector, took a Wanderhalbjahr, and then, after a detour as a prospective student of Dick’s own advisor, Theodosius Dobzhansky, called up Dick to say I was ready to join his lab. Unfortunately, he’d taken a position at Harvard’s Museum of Comparative Zoology, had forgotten about me while negotiating the transfer of his five Chicago students, and I was stuck. I had to wangle myself into Harvard on my own, and managed to do so with the help of E. O. Wilson, a story I told here. I was in Dick’s lab for five years as a grad student and then, unable to find a job, I stayed on for another year as a postdoc.

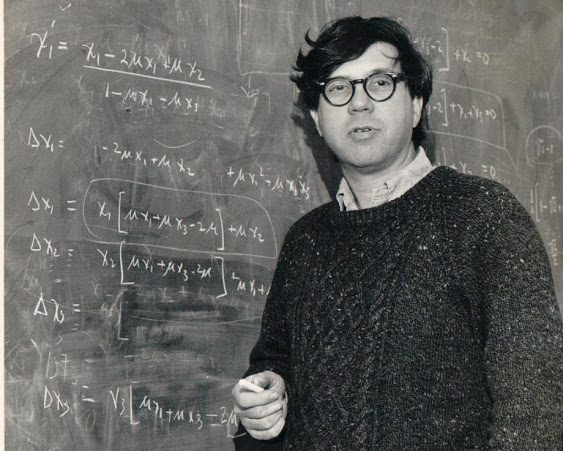

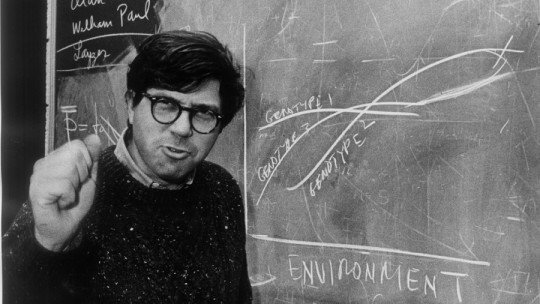

Here’s what Dick looked like about the time I entered his lab. Source.

Dick ran his lab as an egalitarian commune. His office was no fancier than ours, and all the offices were set around a large room containing a ten-foot map table procured from the geographers at Harvard. You couldn’t get to your office without passing that table, which of course was Dick’s design to facilitate interaction. A lot of science was designed and vetted at that table.

Why was he such a good advisor? For one thing, his lab was always full of smart people to learn from: not just the other students, but a constant parade of visiting scholars and luminaries who were passing through or staying a few months. In that way you got to meet almost everyone in evolutionary genetics. You can see the breadth of Dick’s academic lineage here (note: it goes on for several pages). Dick himself was fiercely smart, a terrific writer, and ferociously eloquent, which, while giving us all a role model, made some of us discouraged, realizing we’d never even get close to his level of achievement and intelligence. For two years I thought about dropping out of Harvard, but realized, in the end, that Dick was not typical of people in the field and that, with hard work, I might accomplish something worthwhile.

As an advisor, Dick insisted that you find your own Ph.D. thesis project. As he told me, when he went to work in Theodosius Dobzhansky’s lab, and was looking for a research problem, Dobzhansky told him, in his nasal Russian voice, “I have my research problem. What’s yours?” And so we had to find our own. Unlike many advisors (whose proportion is increasing over time), Dick did not tell you to do research that somehow slotted into his NIH grant or his own research plan. You thought up your project, and he funded it.

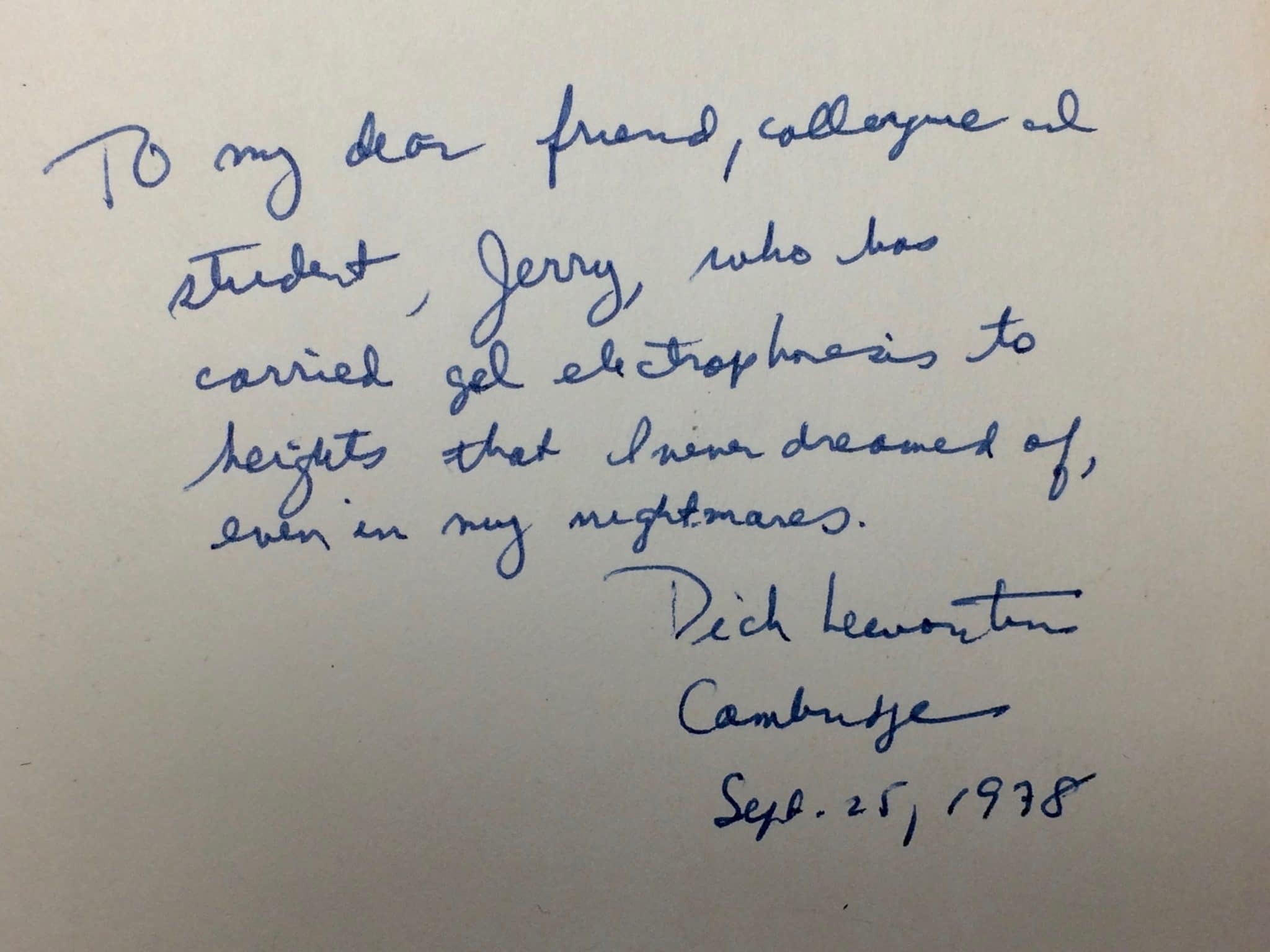

The result was that every student in the lab worked on a very different problem, though the overriding theme of the lab, and of Dick’s later work, was measuring the degree of genetic variation in natural populations. Dick and Jack Hubby had pioneered the use of gel electrophoresis at Chicago: a way to visualize variant forms of enzymes produced by mutation. His goal, and the theme of his 1974 book The Genetic Basis of Evolutionary Change, was to measure the amount of genetic variation at different loci in the genome, and then to understand why it was there. (That, too, had been a major goal of his advisor Dobzhansky.) My own contribution was to expand electrophoresis by changing the biochemical conditions of running gels, which revealed a tremendous increase in the amount of variation at many loci. But that only increased the puzzle. Dick’s solution in his 1974 book proved unsatisfactory, and we still don’t understand the reason for so much variation, though the variants could well be selectively equivalent (“neutral”).

Lewontin in his office door labeled “Dr. O. Sophila”. You can see a bunch more pictures taken when I was in the lab at this post. Dick’s attire was always the same: a work shirt, khaki pants, and work boots (topped with a green sweater in winter). We once found a label that had fallen out of his shirt, and it read “Brooks Brothers Gentleman’s Work Shirt”. We gave him a lot of guff about that! Some Marxist!

Besides the independence he afforded us, Dick was always available to talk or provide moral or financial support. His office door was always open, and if you needed an expensive piece of equipment, all you had to do was ask. He also kept the lab afloat in strong coffee, which was available for purchase with grant funds from the departmental stockroom. I remember that the NIH once audited the lab’s finances, and the auditor, seeing the huge budget for canned coffee, asked Dick, “What is all this coffee for?” Dick responded, “For drinking.”

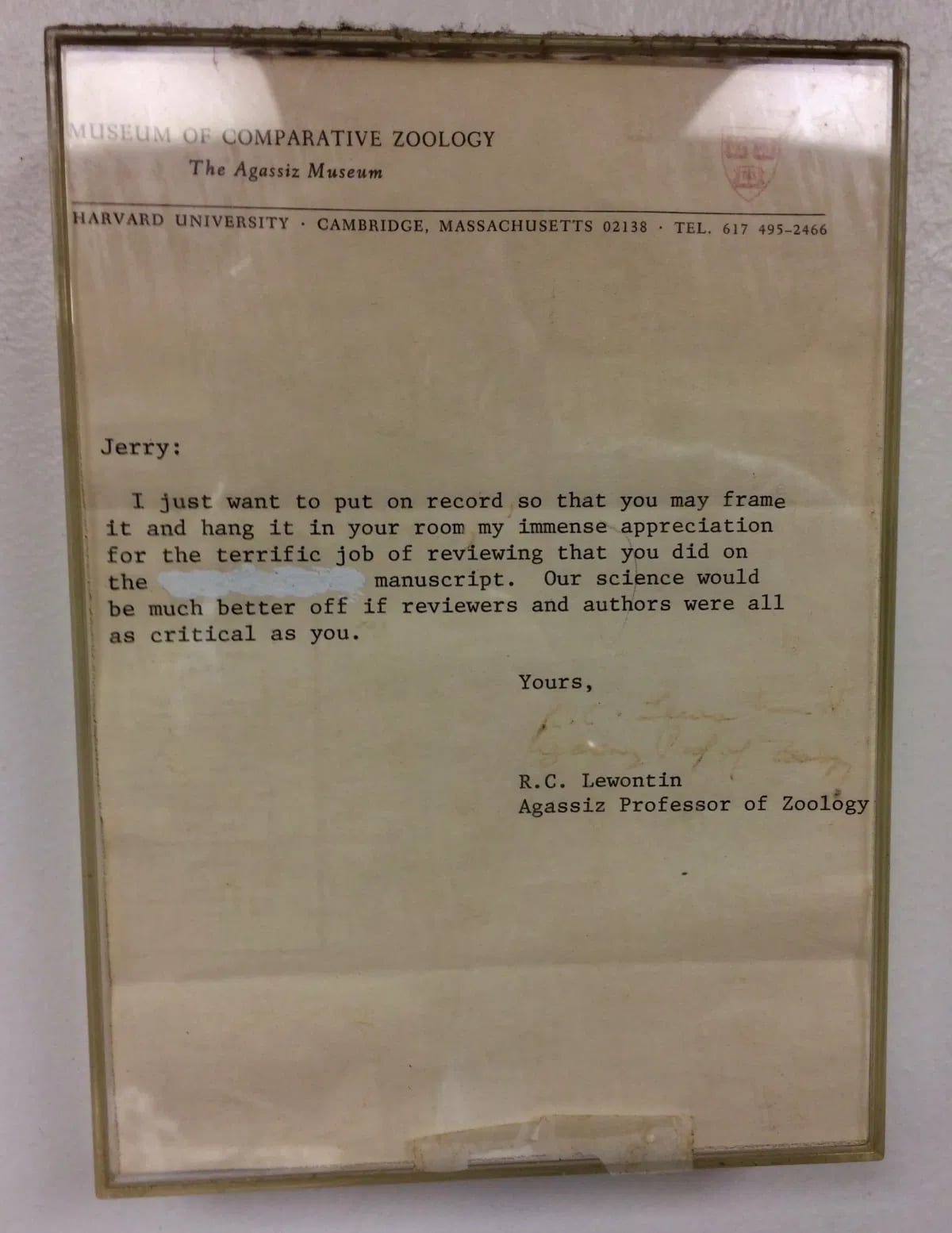

Perhaps most important, Dick had a strong sense of ethics which he took care to instill in all of us. If he thought a scientist was overselling their data, he would write them off—forever. (I won’t name names.) He refused to put his name on any papers from his lab in which he didn’t have a substantial role. I remember when I wrote my first paper about gel electrophoresis, I typed out a draft and put, on the author line “Jerry A. Coyne and Richard C. Lewontin.” I put it on his desk for vetting.

The next day the paper was returned to me with, among the other comments, his name crossed out as author. He told me, “Don’t ever do that again.” It was drummed into us that adding your name to a student’s paper was bad form, which caused what he called “The Matthew Effect” (from the Biblical verse, “For to every one who has will more be given, and he will have abundance; but from him who has not, even what he has will be taken away.”) Taking credit for your students’ work, he said, was a cheap way to make a name for yourself, which should be made based on your own work and ideas. Dick didn’t count providing research advice or helping rewrite papers as a “contribution.”

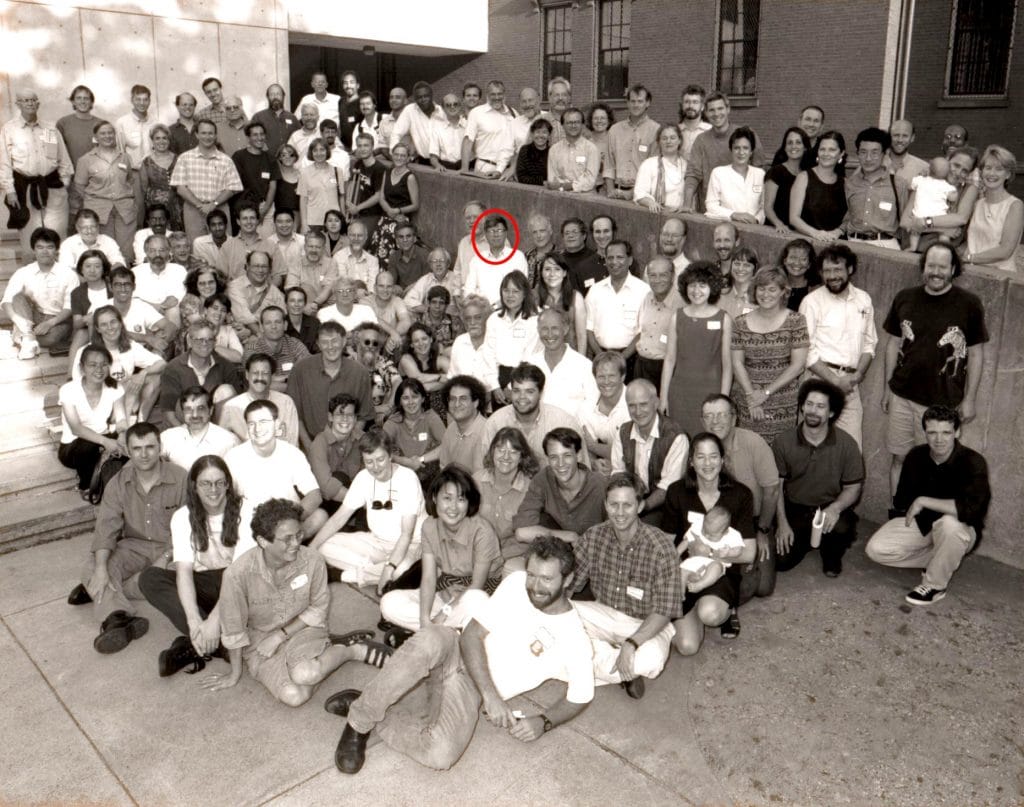

When we held a celebration in his honor since he showed no signs of retiring in 1998, 150 of his colleagues showed up at “DickFest”. Here’s the gang; you may recognize some of the famous scientists in here. Andrew Berry and I organized it; it was Andrew who informed me yesterday of Dick’s death. (Andrew is in the very front of the photo below.) I’ve circled Dick.

DickFest ended with a celebratory meal in the very corridors of Harvard’s Museum of Comparative Zoology. At the end, we asked Dick to say a few words, and he stood up briefly in front of a tank containing a coelacanth preserved in formalin. (He noted the irony of that.) But his brief talk had only one point: “DO NOT PUT YOUR NAME ON YOUR STUDENTS’ PAPERS”. That was the message he wanted to impart, and one he himself got from Dobzhansky, who adhered to that practice as well. And Dobzhansky got it from Thomas Hunt Morgan, the Nobel Laureate who was also generous with credit. When it came my turn to say a few words at CoyneFest five years ago, I said exactly the same thing.

Sadly, the competition for fame and, especially, jobs is such that few professors can afford to leave their names off student papers: they are mostly lab managers and do little science with their own hands.

I find it hard to recount Dick’s scientific accomplishments—not because I don’t know them, but because they’re already well known and you can read about them in many places, including here and here. He made fundamental contributions in theoretical population genetics, in experimental population genetics (out of his lab came the first assays of genetic variation at individual loci using both electrophoresis and DNA sequencing), and even in ecology. He never wrote a trivial paper. I will leave it to others, in the spate of obituaries to come, to recount his achievements in detail.

Dick was an avowed Marxist, and on this we disagreed. But he kept his lab’s science separate from his politics, and it caused no friction. It did motivate both him and Steve Gould (also at Harvard) to attack biological determinism and especially sociobiology, a fight that persisted throughout my time at Harvard. E. O. Wilson, the founder of sociobiology, had his lab only one floor up from ours. They did not speak to each other when I was there, though it was Ed who helped recruit Dick to Harvard from Chicago.

Lewontin was a prolific author of popular pieces, especially in the New York Review of Books. You can read many of those article here. He was a terrific writer, but didn’t have the ambition to be a public figure on the order of, say, Steve Gould or Carl Sagan. When he was elected to the National Academy of Sciences, he resigned his membership after finding out that some of the members were working for the Department of Defense.

Eventually Dick did retire, but he never seemed to age. I don’t think his hair turned gray until he was about 75. In the last decade or so his short-term memory began to fade, though he always could remember the past. In 2009 I interviewed him for several hours about his life and career for a piece for Current Biology, but it went on for so long that I couldn’t find a way to shorten or publish it. I still have a recording of the interview that I need to place somewhere, and may make it available to readers.

I’ll end by alluding to an anecdote I’ve told before, recounting how Lewontin caught me buck naked in his office one night. You can read about it here; the nudity, while embarrassing, had nothing to do with sex. It’s a tribute to Dick’s sense of humor that he accepted my explanation and then forgot about it.

A few photos and a video that will give you a sense of Lewontin’s presence…

To give you a sense of what talking to Dick was like, here’s a video in which he discusses diverse matters with Harry Kreisler on a visit to Berkeley to give a series of lectures. Kreisler’s first question is “What drew you into the sciences?” Dick’s answer: “A charistmatic high school teacher.” Dick was one of those charismatic teachers and, along with Bruce Grant of The College of William and Mary, was one of the two teachers who drew me into evolutionary biology.

Note the work shirt, khakis, and green sweater.

And so it’s goodbye at last, Dick. It was great having you on loan from the Universe for so long.