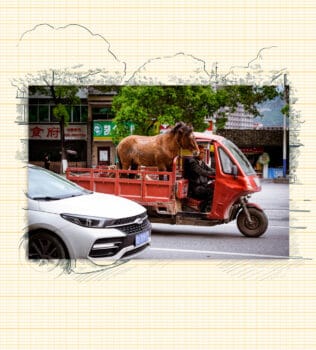

These photographs were made during a trip to Guizhou Province visiting people and sites linked to China’s targeted poverty alleviation programme. The drawn lines extending on top of the images remind us of architectural sketches. Socialism, after all, is about the constant work of construction. This visual language speaks to the name of the series of publications on socialist construction that this study inaugurates.

Part I: Introduction

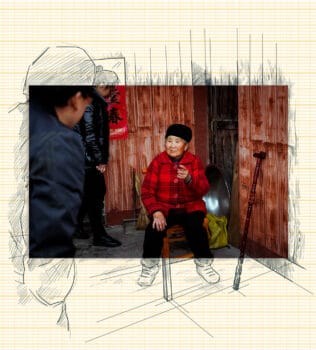

Grandma Peng Lanhua in her two-hundred-year-old home, renovated and serviced with electricity, running water, and satellite television in the village of Danyang, Guizhou Province, April 2021.

Grandmother Peng Lanhua lives in a two-hundred-year-old rickety wooden house in a remote village of Guizhou Province. Born in 1935, she grew up in a China that was under Japanese occupation and entered adolescence during the Chinese Revolution.

Peng is one of the few people in her community who did not want to relocate as part of the government’s poverty alleviation programme when the government designated her house unsafe to live in. Since 2013, eighty-six other households whose houses were deemed too dangerous or for whom jobs could not be generated locally were moved to a newly built community an hour’s drive away. But Peng has her reasons for not moving. She is eighty-six years-old and lives with Alzheimer’s disease. In addition to low-income insurance and a modest pension, she receives supplemental income from a new grapefruit company that leased her family’s land. The company, whose dividends are distributed to villagers like Peng as part of the national anti-poverty efforts, was established to develop the local agricultural industry. Peng’s daughter and son-in-law live next door in a two-storey house they built with government subsidies. Her children are employed. In other words, her basic needs are cared for, and relocation is voluntary.

‘We can’t force anyone to move, but we still have to provide the “three guarantees and two assurances”’, says Liu Yuanxue, the Party cadre sent to live in the village to see that every household emerges from extreme poverty. He is referring to the government poverty alleviation programme’s guarantee of safe housing, health care, and education, as well as being fed and clothed. Liu visits Peng on a monthly basis, as he does with all the households in the village. Through these visits, he comes to know the details of each person’s life.

‘The floor is too messy’, Liu says, jokingly reprimanding Peng’s daughter-in-law as he enters the large wooden house. She is also a member of the Communist Party of China. On the wall, a poster of Chairman Mao and, next to him, President Xi Jinping, pay homage to two of China’s socialist leaders who bookend the course of Peng’s life. Below their portraits sit a weathered table and a dusty terracotta water jug, an internet router flashing green beside them. A string of ethernet cables and wires stretch to different corners of the house (each house gets free internet and CCTV satellite television for three years before a subsidised rate sets in). There are energy-saving lightbulbs in each room and a satellite dish installed next to Peng’s hanging laundry. An extension of the house was built with a toilet and shower equipped with solar-heated running water, the mud floor poured over with concrete. As Lenin said, ‘Communism is Soviet power plus the electrification of the whole country’. Strengthening the Party in the countryside and meeting the concrete needs of the people have been pillars in China’s fight against poverty. Liu’s visit to Peng’s house is just one everyday scene in that process.

The fact that Peng has lived in this house for half a century is also a product of the Revolution; in the 1970s, during the Cultural Revolution, the house was confiscated from a rich landlord and redistributed to three poor peasant families, including Peng’s. That cadres like Liu visit her on a monthly basis, that her house has been made safe to live in through the recent renovations, and that there is internet to connect the poorest of rural villages with the world is a continuation of this revolutionary history. After all, ensuring that the country’s workers and peasants like Peng get housed, fed, clothed, and cared for is part of China’s long struggle against poverty and a fundamental stage in constructing a socialist society.

The Greatest Anti-Poverty Achievement in History

On 25 February 2021, the Chinese government announced that extreme poverty had been abolished in China, a country of 1.4 billion people. This historic victory is a culmination of a seven-decade-long process that began with the Chinese Revolution of 1949. The early decades of socialist construction laid the foundation that was deepened during the reform and opening-up period. During this time, 850 million Chinese people were lifted and lifted themselves out of poverty; that is to say, 70 percent of the world’s total poverty reduction took place in China. In the most recent ‘targeted’ phase that began in 2013, the Chinese government spent 1.6 trillion yuan (US$246 billion) to build 1.1 million kilometres of rural roads, bring internet access to 98 percent of the country’s poor villages, renovate homes for 25.68 million people, and build new homes for 9.6 million others. Since 2013, millions of people, state-owned and private enterprises, and broad sectors of society have been mobilised to ensure that–despite the pandemic–China’s remaining 98.99 million people from 832 counties and 128,000 villages exit absolute poverty.1

In 2019, as China entered the last stages of its poverty eradication scheme, UN Secretary General Antonio Guterres said, ‘Every time I visit China, I am stunned by the speed of change and progress. You have created one of the most dynamic economies in the world, while helping more than 800 million people to lift themselves out of poverty–the greatest anti-poverty achievement in history’.2

While China has been fighting poverty, the rest of the world, especially the Global South, has experienced a downward turn. United Nations agencies report a great reversal in poverty elimination outside of China: in 2020, over 71 million people–most of whom are in sub-Saharan Africa and southern Asia–slipped back into poverty, marking the first global poverty increase since 1998.3 It is estimated that the economic crisis accelerated by the pandemic will drive a total of 251 million people into extreme poverty by 2030, bringing the total number to over one billion.4 That China was successful in combatting poverty in a time of such reversal is neither a miracle nor a coincidence, but rather a testament to its socialist commitment. This stands in contrast to capitalist societies’ indifference to the needs of the poor and the working classes, whose conditions have only worsened during the pandemic.

A mural of Mao Zedong displayed in a rural village and local ‘red tourism’ attraction in Wanshan District, Guizhou Province, April 2021.

This study looks into the process through which China was able to eradicate extreme poverty as a fundamental step in constructing socialism. Based on a range of Chinese and English sources, the study is divided into five key parts: historical context, poverty alleviation theory and practice, targeted poverty alleviation, case studies, and the challenges and horizons ahead. Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research also conducted interviews with leading Chinese and international experts and made field visits to poverty alleviation sites in Guizhou Province, where the last nine counties lifted out of poverty are located. There, we visited poor villages, industrial projects, and relocation sites. We spoke with peasants, Party cadres, business owners, workers, youth, women, and elders who have been directly impacted by and have participated in the fight against poverty. Woven throughout the text, their stories are just a few among the millions who have contributed to this historic process.

Part II: Historical Context

Meeting the People’s Increasing Needs for a Better Life

My mother has two daughters, a young son who is now working in Guangzhou, and seven grandchildren. She has worked really hard to support her three children’s educations. She herself was only able to finish the second grade at primary school and started working soon afterwards by selling vegetables, going out very early in the morning and coming home late at night. Life was really tough when I was young. We ate corn grits all the time and never had rice. Now mother is here, cooking meals for the children, buying groceries, and taking her walks now and then. We would be worried if she stayed alone in her old home. Now it’s much easier for her to go back, as it only takes two or three hours. She travels back to her old home on special occasions. Sadly, my father, who had never been here, passed away a couple of years ago. His greatest hope was to come and visit here, but he died of a brain haemorrhage.

– He Ying, chairman of the All-China Women’s Federation and deputy secretary of the Party branch of the Wangjia community, Wanshan District, Tongren City.

He Ying is a relocated member of the Wangjia community, where she became a Party leader. Her mother is sixty-nine years old, just three years younger than the Chinese revolution. Her lifetime traces the multigenerational struggle against poverty that the country has undertaken. Days before the official proclamation of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) on 1 October 1949, Chairman Mao Zedong said: ‘The Chinese people, comprising one quarter of humankind, have now stood up’.5 China’s national liberation came after what is referred to as a ‘century of humiliation’ at the hands of European colonial powers, a bloody civil war with Nationalist forces, and fourteen years of resistance against Japanese fascism that claimed up to thirty-five million Chinese lives.6 Internally, the Nationalist Party, warlords, and feudal landlords prioritised their class interests over the well-being of the people and the country.

During this period, China would go from being the biggest global economy to one of the world’s poorest countries. Accounting for one-third of the global economy in the beginning of the nineteenth century, the country’s GDP would fall to less than 5 percent by the PRC’s founding. In 1950, only two Asian and eight African countries had lower per capita GDPs than China: Myanmar, Mongolia, Botswana, Burundi, Ethiopia, Guinea, Guinea Bissau, Lesotho, Malawi, and Tanzania.7 In other words, the PRC was the eleventh poorest nation in the world upon its founding. When the communists came into power, they were faced with the challenge of reversing the country’s long term economic and social decline, beginning with meeting the basic needs of the country’s impoverished peasants and working class.

From 1949 to 1976, under Mao’s leadership, the Chinese government focused on improving the quality of life for its population, which had grown from 542 to 937 million people.8 In the first years of this period, poverty was addressed by transforming private ownership of the means of production into public hands and redistributing land from landlords and warlords to poor peasants. Poverty, after all, is an issue of class struggle. By 1956, 90 percent of the country’s peasants had land to till, 100 million peasants were organised in agricultural cooperatives, and private industry was effectively abolished. People’s Communes organised collective ownership of the land and means of production and distributed collective wealth, enabling the agricultural surplus to be invested into industrial development and social welfare.9

In the twenty-nine-year pre-reform period (1949-1978), China’s life expectancy increased by thirty-two years. In other words, for every year after the Revolution, more than one year was added to the life of an average Chinese person. In 1949, the country’s population was 80 percent illiterate, which in less than three decades was reduced to 16.4 percent in urban areas and 34.7 percent in rural areas; the enrolment of school-age children increased from 20 to 90 percent; and the number of hospitals tripled. The decentralisation of the health and education systems from elite urban centres to poor rural areas was key. This process included establishing middle schools for workers and peasants and dispatching millions of barefoot doctors to the countryside. Significant advances were made in women’s participation in society, from abolishing patriarchal marriage customs to increasing access to education, health care, and childcare.10 From 1952 to 1977, the average annual industrial output growth rate was 11.3 percent.11 In terms of productive capacity and technological development, China went from not being able to manufacture a car domestically in 1949 to launching its first satellite into outer space in 1970. The Dongfanghong satellite (meaning ‘The East is Red’) played the eponymous revolutionary song on loop while in orbit for twenty-eight days.12 The industrial, economic, and social gains in the transition to socialism under Mao formed the foundation of the post-1978 period.

By the 1970s, it became clear that China’s economy required an infusion of technology and capital, and that it needed to break its isolation from the world market. As China’s leader Deng Xiaoping later wrote, ‘Pauperism is not socialism, still less communism’.13 The government introduced a range of economic reforms, including opening the economy to the world market, but–because China remained a socialist country–the public sector remained dominant and free of foreign control.

During this period, China’s economy grew at a sustained pace never before seen in human history. Between 1978 and 2017, China’s economy expanded at an average rate of 9.5 percent per year, growing in size by almost thirty-five times.14 Economic growth, however, is not an end in itself, but a means to improve the lives of the people. Between 1978 and 2011, the number of people living in absolute poverty dropped from 770 million (80 percent of the population) to 122 million (9.1 percent), measured by setting the poverty line at 2,300 yuan per year.15

Pursuing rapid economic growth, however, came with great environmental and social costs. Mass migration to the cities heightened the rural-urban disparity, and the focus on eastern coastal industries left the western and central regions heavily underdeveloped. According to the World Bank, China’s Gini coefficient (a measure of inequality based on income) increased from 29 percent in 1981, peaking at 49 percent in 2007, and falling to 47 percent in 2012.16 Socially, this period produced unequal access to public services such as pensions, social insurance, education, and health care. Environmentally, rapid development took a toll on the country’s air, water, and land.

It is not surprising that addressing inequality became a principal task under President Xi (2013-present). At the nineteenth National Congress of the CPC in 2017, the twice-a-decade event that determines the national policy goals and election of top leadership, Xi spoke of the new era of socialism and, with it, the evolution of the principal contradiction faced by Chinese society:

As socialism with Chinese characteristics has entered a new era, the principal contradiction facing Chinese society has evolved. What we now face is the contradiction between unbalanced and inadequate development and the people’s ever-growing needs for a better life. China has seen the basic needs of over a billion people met, has basically made it possible for people to live decent lives, and will soon bring the building of a moderately prosperous society to a successful completion. The needs to be met for the people to live better lives are increasingly broad. Not only have their material and cultural needs grown; their demands for democracy, rule of law, fairness and justice, security, and a better environment are increasing. At the same time, China’s overall productive forces have significantly improved and in many areas our production capacity leads the world. The more prominent problem is that our development is unbalanced and inadequate. This has become the main constraining factor in meeting the people’s increasing needs for a better life.17

Peasant workers till the land in an organic bamboo fungus company, which was established to help lift Longmenao, a village that is officially registered as poor, out of poverty in Wanshan District, Guizhou Province, April 2021.

The reform and opening-up period is therefore seen as the pre-condition for building a modern socialist country. It is during this period when two of the three official strategic goals were achieved, ensuring that the people are have a decent standard of life and that their basic needs are met. Continuing the work of poverty alleviation and ensuring that poor people enter a ‘moderately prosperous society’ (xiaokang) in the rest of the country is a final step in this period. In the years since Xi’s speech, China has mobilised its people–specifically the poor themselves–as well as the government and the market to eliminate extreme poverty, marking a key phase in the transition to socialism.

Part III: Poverty Alleviation Theory and Practice

One Income, Two Assurances, and Three Guarantees

China’s elimination of extreme poverty comes a decade ahead of the UN’s 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, which set ‘eradicating poverty in all its forms and dimensions, including extreme poverty’ as its principal target.18 While millions of Chinese people emerged from poverty during the phase of rapid economic growth, economics itself cannot explain this achievement.

For this study, we spoke with Justin Lin Yifu, former chief economist of the World Bank (the first from the Global South) and founder of New Structural Economics. Lin is also a standing committee member of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Congress National Committee and a professor at Peking University. Lin classifies two primary approaches to poverty reduction, which he calls ‘blood transfusion’ and ‘blood generation’. The former–a preferred model in Western economies–is characterised by humanitarian aid or welfare mechanisms to guarantee that basic needs are met. Meanwhile, the latter describes development-oriented poverty alleviation that creates employment and increases the incomes of the poor. These two approaches alone, however, were unable to eliminate poverty in the poorest pockets of China. According to Lin, ‘In areas that are short of natural resources, far away from the market, and have poor transportation and infrastructure, such as the “Three Regions and Three Prefectures”,19 targeted assistance is needed’.

The comprehensive concept of targeted poverty alleviation–officially implemented in 2015, concluding at the end of 2020–was developed and innovated based on decades of domestic and international experiences. ‘China’s poverty alleviation’, Lin summarises, ‘is a growth-driven, government-led strategy that combines social support and the peasants’ own effort, features the “blood generating” or development-oriented pattern, and guarantees basic needs through social security’. Stressing the role of government leadership, he says: ‘In contrast to the rest of the world, the Chinese government has played a crucial part. Poverty eradication would not have been achieved merely through the role of the market had the government not paid great attention to the issue of the poor people’. In other words, a combination of the ‘visible’ and ‘invisible hand’, together with the mobilisation of broad sectors of society, was the hallmark of China’s poverty alleviation in this ‘targeted’ phase.

China’s Targeted Poverty Alleviation (TPA) programme can be summarised by one slogan: one income, two assurances, and three guarantees. Regarding income, the international poverty line is set by the World Bank at US$1.90 per day, measured in 2011 prices and based on the average poverty line of the world’s fifteen poorest countries. China’s poverty line was last raised to 2,300 yuan per year in 2011 (set at 2010 prices), which represents US$2.30 per day when adjusted to Purchasing Power Parity (PPP), exceeding the World Bank standard. Adjusted to 2020 prices, the annual minimum income is 4,000 yuan, while the per capita income under the targeted alleviation programme of 10,740 yuan per year is much higher.20

Understanding that poverty cannot be addressed by income distribution alone, China’s programme takes on a multidimensional approach. First theorised by Nobel Laureate Amartya Sen, the concept of multidimensional poverty looks at the intersecting and complex factors associated with poverty that are not accounted for just by measuring income. Elaborating upon Sen’s work, the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and the Oxford Poverty and Human Development Initiative adopted the Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI) in 2010, measuring ten indicators across the three dimensions of health, education, and basic infrastructural services. Their 2020 report, launched a decade after MPI’s adoption and a decade before the Sustainable Development Goals’ (SDG) deadline, found that 1.3 billion people, or 22 percent of the world’s population, live in multidimensional poverty.21 In comparison, according to the US$1.90-a-day poverty line, 689 million people–or 9.2 percent of the global population–lived in extreme poverty in 2017, prior to the pandemic.22

First Secretary Liu Yuanxue speaks with a local villager during routine home visits in the village of Danyang, Wanshan District, Guizhou Province, April 2021.

In addition to a minimum income, China’s poverty alleviation programme ensures that five other indicators are met: the ‘two assurances’ of food and clothing and the ‘three guarantees’ of basic medical services, safe housing with drinking water and electricity, and free and compulsory education, which in China is for nine years. We spoke with Wang Sangui, dean of the National Poverty Alleviation Research Institute of Renmin University about the relationship between China’s indicators and the MPI framework: ‘Multidimensional Poverty is only seen as a research approach’, he said, ‘and so far has not been adopted by any country to measure the size of the poor populations at the national level because of its great complexity’. However, by including the five key indicators, he adds, ‘In fact, China has followed a multidimensional approach in poverty eradication’. As an expert advisor to the State Council Leading Group Office of Poverty Alleviation and Development, Wang helped develop the standards for China’s programme. ‘How do you classify drinking water as safe? First, the basic requirement is that there must be no shortages in water supply. Second, the source of water must not be too far, no more than twenty minutes round-trip for water retrieval. Last, the water quality must be safe, without any harmful substances. We require test reports that confirm the water quality is safe. Only then can we say that the standard is met’.

Part IV: Targeted Poverty Alleviation

Don’t Use a Grenade to Blast a Flea

Targeted poverty alleviation, also known as precise poverty alleviation, was introduced for the first time during President Xi’s visit to Shibadong village in Hunan Province in November 2013. ‘Don’t use a grenade to blast a flea’, Xi advised the local government on how to address the root causes of poverty. Instead, he said, act as an embroiderer approaching an intricate design. This approach was implemented as the government strategy in 2015, guided by four questions: Who should be lifted out of poverty? Who carries out the work? What measures need to be taken to address poverty? How can evaluations be done to ensure that people remain out of poverty?

Defining Poverty: Who Gets Lifted?

On 28 August 2018, I came to Danyang, whose Party organisation was considered ‘weak and loose’ and whose work had not been pushed hard enough, which was why I was sent by the higher-level authorities to strengthen the building of the organisation. The organisation gave me a brief report about the villagers at first, and I started by touching base with the people to find out which households were the targets of poverty alleviation. Otherwise, the work wouldn’t be conducted properly. To get closer to the people, I had to understand human nature well […] The local people were poor for many reasons, including water shortages, low crop yields, diseases, disabilities, and the lack of education of children. Their problems and conflicts had been passed from generation to generation.

– Liu Yuanxue, first secretary stationed in the village of Danyang, Wanshan district, Tongren City, Guizhou Province.

Knowing who the poor are in a country of 1.4 billion people is an enormous undertaking. Recognising the limitations of a sampled-data statistical method, China moved towards a household identification system, which means getting to know every single poor person in the country, their conditions, and their needs. This was done through a combination of sending people to the villages, practising grassroots democracy, and deploying digital technologies. In 2014, 800,000 Party cadres were organised to visit and survey every household across the country, identifying 89.62 million poor people in 29.48 million households and 128,000 villages. More than two million people were then tasked to verify the data, later removing inaccurately identified cases and adding new ones.23

While income is the primary deciding factor, housing, education, and health are also taken into consideration when listing a ‘poverty-stricken household’. Village committees, township governments, and the villagers themselves are mobilised to assess the status of each household. Public democratic appraisal meetings, for example, are held to facilitate discussions among community members about each family’s situation and whether they should be removed from or added to the poverty registration list.24 This on-the-ground process was paired with the creation of an advanced information and management system, touching on all parts of the poverty alleviation process across the country. Big data is used to monitor the situation of each of the nearly 100 million individuals, facilitate information flow between governmental departments, and identify important poverty trends and causes.25 Mobilising the people and gaining public support are at the heart of the effort to carry out this work.

Mobilisation: Who Does the Lifting?

Move Amongst the People as a Fish Swims in the Sea

Record of Visit, 10 June 2019: Today I received a call from He Guoqiang. He said a door lock [in] his resettlement flat was broken. I went to his home and helped him contact the property management team and the construction crew for repairs. I took this opportunity to teach him to exercise his rights as a homeowner and to contact the property management and construction crew. He Guoqiang said the next time he encounters such a problem, he [will] know how to solve it.26

– He Chunliu, a thirty-four-year-old woman of Bouyei ethnicity who was stationed as a poverty-relief cadre in Libo County between 2018 and 2020.

There is no organisation without the organisers. As of June 2021, the CPC has more than 95.1 million members–27.45 million of whom are women–and 4.9 million primary level Party organisations, which includes villagers’ committees, public institutions, government-affiliated organs and enterprises, and social organisations.27 If the CPC were a country, it would be the sixteenth most populous in the world.

There is no organisation without the organisers. As of June 2021, the CPC has more than 95.1 million members–27.45 million of whom are women–and 4.9 million primary level Party organisations, which includes villagers’ committees, public institutions, government-affiliated organs and enterprises, and social organisations.27 If the CPC were a country, it would be the sixteenth most populous in the world.

The targeted phase of poverty alleviation required building relationships and trust between the Party and the people in the countryside as well as strengthening Party organisation at the grassroots level. Party secretaries are assigned to oversee the task of poverty alleviation across five levels of government, from the province, city, county, and township, down to the village. Most notably, three million carefully selected cadres were dispatched to poor villages, forming 255,000 teams that reside there.28 Living in humble conditions for generally one to three years at a time, the teams worked alongside poor peasants, local officials, and volunteers until each household was lifted out of poverty. In this process, many cadres were unable to return home to visit families for long stretches of time; some fell ill in the harsh natural conditions of rural areas and more than 1,800 Party members and officials lost their lives in the fight against poverty.29 The first teams were dispatched in 2013; by 2015, all poor villages had a resident team, and every poor household had an assigned cadre to help in the process of being lifted, and more importantly, of lifting themselves out of poverty.30 At the end of 2020, the goal of eliminating extreme poverty was reached.

Liu Yuanxu, a forty-seven-year-old man with a daughter in her senior year of high school, is among the Party secretaries who were sent in 2018 to Danyang, a village of 2,855 people in the southwestern province of Guizhou. Liu describes arriving in Danyang, where he does not speak the local dialect, and where 137 of the village’s 805 households were designated as poor. He was one of 52 cadres assigned to the village, each with different responsibilities. He told us about his day-to-day work:

I was responsible for five poor households, but it is now for four, since one person died. Back then I visited every family on an electric bike and took care of everything for them. I kept in touch with the young people on WeChat and the elders by phone. They could call me for anything. I went to every villager group to investigate who was nice and who was difficult. I’ve resolved problems through drinks and talks with the villagers who now have a very good relationship with me. Now the government maintains a register of poor households, marginal households, and key households. Digital tools help the government know when people get sick or if those who can work are employed. We also visit the villagers every month to better understand the reality of their situation.

Unlike models that rely heavily on non-governmental organisations and international assistance, China’s poverty alleviation programme draws its strength from mobilising its citizens. Cadres like Liu are an essential bridge between implementing government policy and understanding the concrete conditions and demands of the people. The more than ten million cadres and officials who have mobilised in the countryside have been essential in building public support for and confidence in the Party and the government.

In 2020, Harvard University published a study, Understanding CCP Resilience: Surveying Chinese Public Opinion Through Time, for which they interviewed 31,000 urban and rural residents between 2003 and 2016 about their support for the CPC.31 During this period, Chinese citizens’ satisfaction with their government increased across the board from 86.1 percent to 93.1 percent. The greatest increase in government satisfaction was seen in the rural township-level areas, which increased from 43.6 percent approval to 70.2 percent approval, particularly among lowest-income residents and those from the poorer inland areas. This growing support stems from the increased accessibility and quality of health care, education, and social services, as well as from the improved responsiveness and effectiveness of local government officials. Though the study ended in 2016 before the campaign’s completion, the poverty alleviation programme and the government’s effective response to COVID-19 have continued to build public support.32

Shortly after Wuhan emerged from the COVID-19 lockdown, York University Professor Cary Woo led a survey of 19,816 people across 31 provinces and administrative regions. Published in the Washington Post, the study found that 49 percent of respondents became more trusting of the government following its response to the pandemic, and overall trust increased to 98 percent at the national level and 91 percent at the township level.33 Eliminating poverty and containing the pandemic can be seen as two major victories of China and its people in 2020.

United Front for Poverty Alleviation

Ge Wen is from the eastern city of Suzhou, where she is the deputy director of sales for a culture and tourism company. The government promoted collaboration between the industrialised eastern part of the country with the lesser-developed western regions to support even development across the country. As part of this effort, the company Ge works for was paired with a remote village in Guizhou Province to develop an eco-tourism resort and stimulate the region’s tourism industry. The company invested 130 million yuan to construct infrastructure and renovate homes, which are leased for a twenty-year term by villagers. Of the village’s 107 households, only twenty families–all with the surname Zhang and of the Dong ethnic minority–were still living there when the project began. At the end of the lease, the houses and surrounding amenities will be returned to the villagers, some of whom have been hired as workers at the resort. Ge is one of eight employees assigned by the company to move from Suzhou to bring this project to fruition. The task is not without challenges. In addition to infrequent visits home during her three-year term, she also faced cultural, linguistic, and climate differences. ‘I’m not used to the humidity here’, she told us. High in the mountains of Guizhou, it can rain for months at a time. The location is also remote; when Ge and team were building the resort, the tarmac road to the site had to be excavated manually because the cranes could not be brought in. This stays true to the local saying, ‘Guizhou, where the sky is not clear for three days and flat land does not stretch for three li [1.5 kilometres]’.

Beyond cultivating Party and public support, the poverty alleviation campaign mobilised broad sectors of society to participate in a united front. ‘We should mobilise the energies of our whole Party, our whole country, and our whole society and continue to implement targeted poverty reduction and alleviation measures’, President Xi said in his speech at the Nineteenth National Congress. ‘We will pay particular attention to helping people increase confidence in their own ability to lift themselves out of poverty’.

The objective of achieving common prosperity with the expectation that those who get rich–particularly in the industrialised eastern coastal areas–will uplift the rest is a core element of this approach, and one that lies at the heart of Deng’s often misinterpreted quote, ‘let a few get rich first’. The poverty alleviation campaign followed this principle and used a mass mobilisation strategy reminiscent of the Mao-era to establish East-West cooperation. From 2015 to 2020, nine eastern provincial-level administrative units representing 343 counties invested 100.5 billion yuan in government and social assistance for the western regions, mobilised more than 22,000 local enterprises to invest an additional 1.1 trillion yuan, and exchanged 131,000 officials and technical personnel.34

In 2013, the city of Tongren in the southwestern Guizhou Province, where He Ying relocated and where Liu Yuanxue’s village is situated, was paired with Suzhou, the economic centre of the eastern coastal province of Jiangsu. The collaboration included economic, infrastructural, educational, and technical exchanges. From April 2017 to 2020, Suzhou provided 1.71 billion yuan in financial aid and 240 million yuan in social assistance to implement 1,240 projects. In addition, 285 eastern enterprises developed projects in Tongren, investing 26.41 billion yuan and generating employment for 44,400 people in the poverty alleviation programme. In the process, 19 industrial and agricultural parks were created and targeted projects boosted local tourism by 30 percent. To deepen the political and educational exchange, 5,345 Party cadres, government officials, and technical personnel were transferred from Suzhou to Tongren, including Tongren’s deputy mayor Zha Yingdong, who moved from Jiangsu to Guizhou to lead the poverty alleviation work.35

Beyond East-West cooperation, public and private enterprises, educational institutions, the military, and civil society also made significant contributions. The central departments invested 42.76 billion yuan, which helped bring in 106.64 billion yuan in capital and train 3.69 million grassroots technicians and officials.36Meanwhile, 94 state-owned enterprises invested more than 13.5 billion yuan in 246 counties, implementing nearly 10,000 assistance projects. Of the country’s 2,301 national social organisations, 686 established formal poverty alleviation projects, raising charitable funds and offering voluntary services.37 Through the Ten Thousand Enterprises Helping Ten Thousand Villages campaign, 127,000 private companies participated in supporting 139,100 poor villages that benefited 18 million people.38 The military helped 924,000 people in 4,100 poor villages and contributed to the construction of schools, hospitals, and special industrial projects. The Ministry of Education organised 44 colleges and universities to be part of the campaign, carrying out research projects and dispatching expert and training teams in agriculture, health, urban and rural planning, and education, among other fields.

One such collaboration was the Hebian experiment,39 which brought university experts and students to Hebian village in Yunnan Province, a community that is predominantly made up people of Yao ethnicity. Led by Li Xiaoyun, chair professor at China Agricultural University, the team helped research, raise funds, and develop tourism, educational, and agricultural projects to increase and diversify income for the community. In our interview with Li, he commented on the mass mobilisation that took place:

It is very difficult for people outside of China to understand the poverty alleviation campaign of the last eight years, and particularly how it was organised–especially the remarkable mobilisation. The most difficult question that my friend asked me was, ‘How was the government able to convince everyone to contribute resources and to go to the poor areas?’ This is what we always try to articulate through our very simple statement. This is China’s special political institution. Chinese society is different from Western societies, because it is based on the collective and not on the individual. This is reflected in how the society is organised. The government works with social organisations, where the political and social networks merge into a whole–into a leading force, organised vertically and horizontally, which enables everybody to join this social campaign.

In short, the poverty alleviation programme touched virtually every corner of society. The victory against extreme poverty, therefore, cannot be seen as a singular programme under a singular mandate by the Party and the government. Rather, it should be seen as a mass mobilisation across multiple sectors of Chinese society using diverse and decentralised methodologies at a breadth and scale that is unprecedented in human history.

Methodology: How Did China Alleviate Poverty?

Industry

Resettled residents work in a clothing factory established in the Wangjia community, Tongren City, Guizhou Province, April 2021.

Ms. Liu is one of the top earners on the Yishizhifu short video platform that helps poor peasants generate extra income. She is a peasant and mother who has earned over 200,000 credits (equivalent to about 20,000 yuan) for the videos she makes and posts online, which can be exchanged for goods through the platform. Not only have the videos supplemented her income by providing goods and time-saving appliances such as a rice cooker and a microwave oven; they have also provided her with an outlet to showcase her culture. One of the first women drummers in her community and a member of the Dong ethnic minority group, Ms. Liu uses the platform to post videos of Dong music, crafts, fashion, and drumming. In one video, she stars in a locally produced television drama. ‘We filmed it ourselves,’ she told us. ‘If I told you how we did it, you would be very touched by the process’. As she pointed to the screen, she said, ‘This is me, this is my younger brother, my sister-in-law, and my neighbour’. Together they wrote a script about the story of a young, poor boy who could not find a wife and had to turn to creative methods to attract a suitor.

The introduction of e-commerce in rural areas was a key part of the poverty alleviation programme. Between 2016 and 2020, online businesses in poor counties grew from 1.32 million to 3.11 million, which helped increase rural households’ income while connecting the countryside to online markets.40 One such platform is Yishizhifu, launched in Tongren in June 2020, which trains peasants to produce short videos by setting up over twenty filming studios in poor communities in the city and surrounding villages. Users can upload their videos onto the mobile application and receive points for views that can later be exchanged for products available on the platform. For every minute of video watched, ten credits are awarded and distributed: six to the video producer, one to the viewer, two to the studio, and one to the Yishizhifu platform. Goods such as clothing, household appliances, agricultural products, farming equipment, and even cars are secured through partnerships with state and private enterprises. These businesses donate goods to the platform either to receive tax credits, offload excess stock, or use the platform as a source of free advertising. In this example and countless others, industrial development–facilitated by e-commerce and internet access–is a means of connecting the countryside with the city, generating employment and supplementary income, and building cultural confidence among peasants and the poor.

The targeted poverty alleviation strategy developed five core methods to lift poor people – or, rather, help them uplift themselves–out of poverty: industry, relocation, ecological compensation, education, and socialist assistance. The first of the five core methods is to develop local production. With that goal in mind, public and private sectors got involved to provide poor people with access to financing (loans, subsidies, and microcredit), technical training, equipment, and markets. Through the TPA programme, industrial poverty alleviation policies impacted 98 percent of poor households and established 300,000 industrial bases for agricultural production as well as animal breeding and processing across each of the 832 poor counties. Over 22 million poor people are employed in these bases, plus another 13 million in rural enterprises. Poverty alleviation workshops (small-scale centres of production organised on idle land or in people’s homes) contributed to nearly tripling the per capita income of poor households from 2015 to 2019, reaching 9,808 yuan per year.41 This in turn has helped develop new poverty alleviation models linked to tourism and the green economy.

Relocation

A local food vendor and user of the Yishizhifu short video platform showcases her cooking in the village of Danyang, Wanshan District, Guizhou Province, April 2021.

Atule’er is a village in the mountains of Sichuan Province whose ancestry dates back to the Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368), when it was deemed strategic to farm in the mountains during wartime. At an altitude of 1,400 metres, the village was until recently only accessible through 800 metres of poorly constructed rattan ‘sky ladders’ that dangled from the edge of the cliff. The commute to schools, local markets, health services, and public transport was hours away and dangerous. One of the residents, Mou’se said, ‘It took me half a day to climb down the cliff to buy a packet of salt’. Four years ago, the government spent one million yuan to replace the ladder with a safer steel structure. Mou’se and eighty-three other families in Atule’er resettled in May 2020 during the poverty campaign.42

For families who are living in extremely remote areas or exposed to frequent natural disasters, it is near impossible to break the cycle of poverty without moving to more habitable environments. A total of 9.6 million people–roughly 10 percent of the people lifted from poverty–moved from rural to newly built urban communities. New housing was constructed along with 6,100 kindergartens, elementary, and middle schools; 12,000 hospitals and community health centres; and 3,400 elder-care facilities; and 40,000 cultural centres and venues were built or expanded.

The main challenge when transitioning from the countryside to cities is finding employment for the relocated families. To address the challenge of finding employment for the relocated families, the government developed training programmes and new industries. As a result, 73.7 percent of all of relocated people who are able to work have found jobs and 94.1 percent of relocated families with members who can work have found employment.

Ecological Compensation

A little green button in the Alipay mobile app Ant Forest takes users to a screen with an animated seedling in the middle. In return for walking or using a shared bicycle system rather than private transportation, users are rewarded with green credits that can be exchanged for planting trees on an interactive mobile application. Launched in 2016 by the company then known as Ant Financial Service Group, which is linked to the internet giant Alibaba, the online payment platform encourages its 550 million users to lower their carbon footprint.

Despite the game-like design, the trees are not virtual. As of March 2020, 122 million trees have been planted through Ant Forest, covering 112,000 hectares heavily concentrated in arid regions in Inner Mongolia, Gansu, Qinghai, and Shanxi. As a result, 400,000 jobs were created linking environmental conservation to poverty alleviation in public welfare-protected areas and ecological economic forests. In 2019, Ant Forest won the UN Environment Programme’s top award, Champions of the Earth.43

Ecological conservation and restoration, particularly in designated poor areas, have been among the key methods to address poverty, primarily through job creation in the ecological sector. Since 2013, 4.97 million hectares of farmlands in poor regions have been restored as forests or grasslands. In the process, 1.1 million poor people have been employed as forest rangers, while 23,000 poverty alleviation cooperatives and teams for afforestation (the creation of new forests) have been formed.44 This is part of China’s continual greening efforts over the past two decades. According to the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO), China was ranked as a global leader in reforestation and accounted for 25 percent of the total growth in leaf area between 1990 and 2020.45 The greening efforts have been taken up not only through government efforts, but also through private sector initiatives like Alipay.

Education

When Tibet was formally incorporated into the PRC in 1951, education was controlled by the monasteries with the exception of a few private schools. Schools were reserved for monks and officials, resulting in only 2 percent enrolment of school-aged children. From 1951 to 2021, over 100 billion yuan was spent to develop a modern education system that has attained 99.5 percent enrolment for primary school, 99.51 percent enrolment for middle school, and 39.18 percent enrolment for tertiary-level education as of 2021. In 2012, Tibet was the first among the country’s regions to offer a free fifteen-year education programme from preschool to senior high school, which includes tuition, accommodations, textbooks, meals, transportation, and other costs.46 The policy was expanded to include university students from rural households registered as poor. From 2016 to 2020, 46,700 impoverished undergraduate students benefitted from this policy.47

Education has been central in breaking the cycle of intergenerational poverty. To fulfil the TPA programme’s guarantee of education, great efforts were made to ensure that the 200,000 school dropouts from poor families (as of 2013) had adequate support to return to school. By 2020, 99.8 percent of China’s elementary and secondary schools met the basic educational requirements, with 95.3 percent of schools connected to the internet and equipped with multimedia classrooms. Large governmental funding programmes have offered educational assistance to 640 million people and improved nutrition in schools, reaching 40 million students every year.48

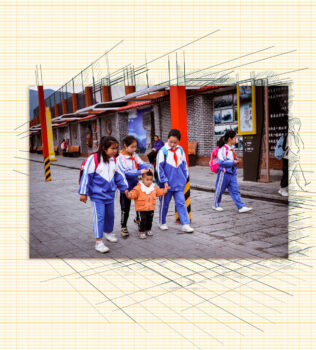

Students on their short walk home from school in the Wangjia community, Tongren City, Guizhou Province, April 2021.

Developing quality educators was also prioritised: 950,000 teachers were recruited through the Special Post Programme to teach in impoverished areas upon graduation. The National Training Programme added an additional 17 million rural teachers to the less-developed central and western regions, 190,000 of them dispatched specifically to remote poor and ethnic minority areas. In line with the socialist tradition, these efforts ensure that young people receive first-hand knowledge of life in the countryside, at the same time cultivating the next generation of educators.

These gains in education were reflected not only in villages, but across the country. In the seventh national census of 2020, the average years of education increased from 9.08 to 9.91 years, while the number of people with tertiary education nearly doubled from 8,930 to 15,467 per 100,000 from 2010 to 2020.49 The profile of those who are able to access tertiary education has also shifted. According to Tsinghua University’s Chinese College Student Survey, from 2011 to 2018, over 70 percent of all first-year students in Chinese universities were the first in their families to attend university, and nearly 70 percent of these students are from rural areas.50 In the World Economic Forum’s Global Gender Gap Report 2020, China ranked first in women’s enrolment in tertiary education, as well as in the proportion of women professional and technical workers.51 The education reforms of the past decade tackled the multidimensional factors of poverty, the urban-rural divide, and gender.

Social Assistance

The final of the five key methodologies employed to alleviate poverty focused on providing social assistance. China’s first social safety net traces its history back to Shanghai’s Urban Minimum Living Guarantee System (dibao) in 1993, which was extended to all urban areas in 1999 and to rural China in 2007.52Under this programme, any household whose per capita income was lower than the local poverty line had the right to apply for social assistance. This is considered the largest cash social assistance programme in the world.53 Dibao was complemented with other programmes for education, healthcare, housing, disabilities, and temporary assistance, while a pension system was established for people in rural areas in 2009 and in urban areas in 2011.

The rural subsistence allowance grew from 2,068 yuan to 5,962 yuan per year from 2012 to 2020;54 9.36 million people have been covered either by these funds or by extreme poverty relief funds, and 60.98 million people receive a basic pension. These programmes cover virtually all rural and unemployed urban residents.55

However, China’s social system is under great strain. Faced with declining birth rates of 1.3 children per woman according to the last census and an aging society, China recorded its first social insurance deficit last year. The number of elders (people above 60 years-old) is expected to reach 300 million by 2025, and the Chinese population is expected to start shrinking by 2050. China is currently undergoing reforms in the urban worker pension system to address the pension deficit, which could reach 8 trillion yuan within the next decade.56

Recognising that disease and poor health are key factors causing rural poverty, improving health care in the countryside has been key to the TPA programme. To improve health provision in poor areas, 1,007 leading hospitals were paired with 1,172 county-level hospitals, which sent 118,000 health workers to establish 53,000 projects across the country. These doctors treated 55 million out-patients and performed 1.9 million surgeries. Meanwhile, 60,000 medical students received free training in return for working in rural medical institutions upon graduation.57

Evaluation: How Is Poverty Alleviation Measured?

‘Can households with immediate relatives who are village cadres be rated as poor?’ students ask in a cross-examination session with the local officials of Pingbian Yi Ethnic Township. Students and professors from Southwest University in Chongqing travelled 300 kilometres to rural Sichuan. They have been trained and assigned by the government to evaluate the successes and shortfalls of the local poverty alleviation efforts. Only the night before do they advise the local officials of the villages that they want to inspect. On these randomised spot-checks, the students visit homes and register their questionnaire answers in a centralised application, review bank statements and housing appraisal certificates, survey housing conditions, and verify whether the indicators have been met.58

To carry out a programme on this scale requires a sophisticated system of checks and balances at every level and in every region. Since 2016, an assessment has been carried out yearly at the national level, led by the State Council Poverty Alleviation Office, the Central Organisation Department, and member units of the State Council Leading Group on Poverty Alleviation and Development.59 Their task is to evaluate the effectiveness of poverty reduction in a given area, including confirming the accuracy of household information, the adequacy of measures taken, and the appropriate use of funds, among other factors. The assessment is carried out in three principal ways: inter-provincial cross-assessment, third-party assessment, and social monitoring.

Inter-provincial cross-assessment: There were twenty-two provinces in central and western China that signed the agreement to cross-examine each other’s work, progress, and the credibility of their reported results.60 Each province sends dozens of Party cadres to perform on-site evaluations to see whether the households were correctly added or removed from the poverty registration list, if adequate assistance was provided, what problems were encountered, and what lessons were learned.

Third-party assessment: The Leading Group Office of Poverty Alleviation and Development entrusted relevant scientific research institutions and social organisations to verify that a county is indeed poverty-free once it is declared so by the local authorities. These teams conducted surveys and field verifications to evaluate the reliability of the data. The third-party assessment agencies were determined through a public bidding process.61 Over the course of the programme, a total of 22 third-party agencies surveyed 531 counties, over 3,200 villages, and 116,000 households in the field.62

Social monitoring: Beyond official evaluations and third-party evaluation processes, the poverty alleviation work was also assessed through random checks performed by cadres. For example, visits were made to poor households to see if the families’ situations were accurately reported, such as by verifying income sources.63

Evaluation results: The systematic evaluation processes revealed issues in the poverty alleviation programme, including the failure to meet the annual poverty reduction goals, mismanagement of funds, falsification of data, inaccuracy in adding and removing poor families from the registration list, and other disciplinary violations.64 Among these problems is corruption, which the Party under President Xi’s leadership has openly addressed and criticised. In 2018, the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection (CCDI), China’s top disciplinary body, established a campaign to fight corruption in the poverty alleviation programme. Since assuming office in 2013, Xi has made anti-corruption a high priority, targeting not only the ‘fleas’, but also the ‘tigers’. From 2012 to the first half of 2020, over 3.2 million officials were punished for corruption-related offenses.65 From January to November 2020, the government found that one third of the 161,500 processed corruption cases–including 18 high-level officials–were linked to poverty alleviation.66 In the process of constructing socialism, combatting corruption is part of the ongoing work of the class struggle that holds accountable those who are illegally profiting from public coffers. Unsurprisingly, the anti-corruption campaign has enjoyed widespread popular support, building confidence in both the Party and the government to stay true to their mandate of serving the people.

Part V: Case Studies

Danyang Village

Spanning 18.9 square kilometres and encompassing a population of 2,850 people (825 households), Danyang is one of the largest villages in the Wanshan district of Tongren City, Guizhou Province in southwest China. Poverty in Danyang stemmed from a variety of factors, including water shortages, low crop yields, diseases, disabilities, and a lack of education for children. Since many young adults left the village for cities to find jobs, children and elders were often left behind.

In August 2018, the forty-seven-year-old district government official Liu Yuanxue was sent to Danyang village as a first secretary (a local leadership position in the Party) to focus on poverty alleviation and Party building work. Since 2013, more than three million first party secretaries and 255,000 teams were dispatched across the country to work as part of the TPA programme for at least two years.

When Liu arrived, there were still 137 poor households (443 people) of the 825 households in the village. The village Party organisation (with fifty-eight members, including one poor member, five female members, and seventeen members over sixty years old) was listed as one of tens of thousands of Party organisations that needed to be strengthened.

According to Liu, a total of fifty-two Party cadres were dispatched from township and district-level governments to assist poor households in Danyang. They are expected to visit each family four times per week and address problems ranging from housing to employment to health care. ‘The Party organisation should take the lead so that their employment and social issues can be addressed’, Liu said.

In Danyang, villagers used to work on their own plots of land, but in 2017, the village founded the cooperative to develop industries ranging from vegetable and fruit production to pig farming and even e-commerce. ‘The rural industry will grow faster and better only after peasants are mobilised and small scattered rural lands are combined into big-scale farming’, Liu told us. ‘We should also guarantee that everyone from the village can benefit from development’.

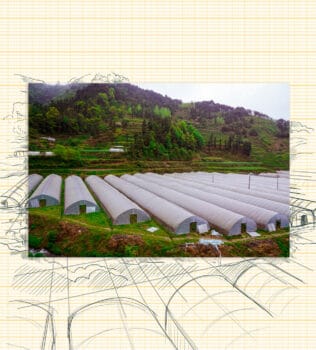

For example, in 2017, 48 peasants in Danyang signed a 10-year contract with the co-op to lease their 100 mu (equivalent to 6.7 hectares) of land to build vegetable greenhouses. The peasants charged an annual rental fee of 800 yuan per mu and the cooperative hired 10 peasants to manage the greenhouses. By 2020, a total of 242,000 yuan in dividends was paid to the villagers. In 2019, with an investment of 4.8 million from government subsidies and company loans, the rural cooperative also established a 13-mu pig farm by collaborating with Wens Foodstuffs Group Co., Ltd. The company provides technology and pig stock while the cooperative provides land and employees. Around 6,000 pigs will be raised every year. Between 2014 and 2018, 132 households totalling 431 people were lifted out of poverty. The last five poor households, totalling 11 people, were lifted out of poverty in 2019.

Wangjia Resettlement Area

With 663 mu (44.2 hectares) of land, the Wangjia community is the largest relocation area in Tongren. Since 2016, a total of 4,322 households (18,379 people) have been relocated from rural villages in Sinan, Shiqian, and Yinjiang counties. Sixty-five percent of the community belongs to eighteen non-Han ethnic groups (the majority of Chinese people are of Han ethnicity). The community is served by a team of eleven cadres who are responsible for all areas of life, work, and Party building, most of whom are elected by the residents every five years.

After relocation, each resident receives 1,500 yuan in living subsidies and an additional 3,000 yuan in compensation if their previous house was demolished. Of those monies, each person pays 2,000 yuan to receive a twenty-square-metre apartment, equalling 100 yuan per square metre (lower than the commercial housing price of 4,000 yuan per square meter in Tongren). The water, electricity, and gas fees are exempted for six months.

The government also built three kindergartens, one elementary school, and one middle school with quality facilities and teachers that have the capacity to educate approximately 2,800 students. Villagers who used to spend forty minutes by bus to get to a hospital or at least one or two hours on foot to get to school are now a five-minute walk from community health centres and schools.

But not everyone can adapt easily to city life after relocation, especially elders who spent almost their entire lives in villages. The community Party branch launched the ‘six firsts’ projects to facilitate the adjustment to city life, teaching newly relocated residents skills from how to use crosswalks and elevators to how to shop at the supermarket. Local students are organised as ‘volunteer grandchildren’ to take care of elders, who are in turn incentivised with credits that can be exchanged for rice to participate in these activities. Serving the people is a value and a practice cultivated amongst the young and the old alike.

To create new employment, the local government renovated a three-story office building into what is called a poverty alleviation mini factory to develop industry. The mini factory created 600 jobs at six firms in the community, including an embroidery workshop, clothing factories, and an artificial intelligence project under China’s leading tech giant Alibaba. The community also encourages rural women to find jobs or start their own businesses, generating income for their families while building their confidence and sense of independence. For example, the local Women’s Federation helps train women and sell their homemade handicrafts.

One factory owner, Gong Changquan, grew up in a county nearby and left home in 1997 to work in the southeastern Guangdong and Fujian provinces. In 2017, at the encouragement of the local government, he returned home to contribute to poverty alleviation. In June 2019, the forty-three-year-old Gong, with an investment of 1.8 million yuan of his own money and 200,000 yuan in government funding, set up a 1,500-square-metre factory, which during peak season can produce daily around 5,000 pieces of clothing to fulfil both domestic and international orders. His rental fees were also waived by the government for three years.

Gong hired sixty-seven workers from the community and pays each worker 2,000 to 3,000 yuan per month after two months’ training.

Greenhouses were introduced to stimulate the local agricultural industry in the village of Danyang, Wanshan District, Guizhou Province, April 2021.

As of May 2021, over 98 percent of the 7,000 working-age people in the Wangjia community are employed. The remaining 2 percent includes those who care for children and people with disabilities. There has only been one family–a couple with disabilities–that decided to move back to their village from the relocation area.

Part V: Challenges and Horizons

Challenges and the Road Ahead

Overcoming extreme poverty in China is an achievement of a size and scale that has never been seen in history. Rather than being the end point, it is one phase in the construction of socialism that must be deepened and expanded. To ensure prosperity in the countryside, the Chinese government has put forth a programme for rural revitalisation to consolidate and expand on the achievements in poverty alleviation. Modernising agricultural production, protecting national food security, developing high-standard arable land, and closing the urban-rural gap are key among the goals of rural revitalisation.67

China is on track to become a high-income country by 2025 at the end of the fourteenth Five-Year Plan period (a high-income country is defined by the World Bank as one that has a gross national income per capita of over US$12,696 by 2020 standards).68 China’s per capita GDP passed the US$10,000 threshold for the first time in 2019, which it maintained in 2020 despite the pandemic.69> Put into context, that is a tenfold increase in the last twenty years, when the country’s per capita GDP was less than US$1,000. As it emerges into high-income status and builds a moderately prosperous society (xiaokang), China is faced with a new era of challenges. Not only is the country faced with ensuring that the people lifted out of poverty remain out of poverty; it also seeks to move beyond a focus on mere survival (in other words, moving beyond extreme poverty) and towards creating a better standard of life for all.

The country’s focus has now moved from extreme poverty to relative poverty, ensuring that more people can participate and benefit from social and economic life. Addressing relative poverty was a key focus of the Fourth Plenary Session of the Nineteenth Central Committee of the Communist Party of China in 2019, for whom improving social assistance and public services such as access to child and elderly care, education, employment, medical services, and housing are key to this long-term goal and ongoing process of eliminating poverty.70

What are the implications for the rest of the world as China moves into the next historic phase of poverty elimination? The historic defeat of extreme poverty and the COVID-19 pandemic does not provide a model that can be directly implanted onto other countries, each of which has a specific history and distinct path to shape. Rather, China’s experience offers lessons and inspiration for the world, particularly for countries in the Global South. The task of uplifting the world’s poor is a key pillar of China’s proposal to build a ‘shared future for humanity’.71 This vision, advocated by President Xi, imagines a future that is based on multilateralism and shared prosperity in the face of Western hegemony.

In its international relations, China has demonstrated its priority to build bridges over militaristic interventions, medical internationalism over privatisation, and infrastructural investments and financial aid that do not come with strings attached. China offers a vision for the Global South that five hundred years of Western imperialism and capitalism has failed to provide. According to the World Bank, the landmark Belt and Road Initiative will directly help uplift 7.6 million people in participating countries out of extreme poverty and another 32 million out of moderate poverty. China is promoting hundreds of other projects based on multilateral cooperation in trade, infrastructure, green industry, education, agriculture, health care, and people-to-people exchanges that encourage the development of countries and people in the Global South.72

‘Poverty alleviation is the single best story that China can tell because it is so rich and so ubiquitous in terms of its importance in the world’, Robert Lawrence Kuhn, an expert on China and the creator of the documentary Voices from the Frontline: China’s War on Poverty (2020), said in a conversation Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research. However, Western-controlled media has stifled these stories and prevented them from reaching much of the world. In one of many such examples, Kuhn’s documentary, jointly produced by PBS (US) and CGTN (China), was taken off-air for ‘not meeting accepted standards of editorial integrity’, Kuhn explained. ‘We had 4,000 broadcasts on PBS, and the irony was that the one production that caused a lot of problems was on poverty alleviation, which was the topic that was the most neutral and beneficial to the world. It is a sign of the times. It is not a superficial problem but a very serious one’.

This study aims to bring forth some of these stories, both from those who were lifted–and lifted themselves–out of poverty and from those who helped do the lifting. It seeks to shine a light on some of the complexities, theories, and practices involved in this historic feat. Building a world in which poverty is eradicated is an essential part of constructing socialism. To be able to study, have a house, be well fed, and enjoy culture are aspirations shared by the working classes and poor across the world. It is part of the process of becoming human.

Epilogue

He Ying wakes up every morning at 7:30am, ready to serve her community of over 80,000 people who have recently relocated. She picks her youngest son up from school at 4:30 pm, a five-minute walk away from her apartment. ‘Upstairs is where I live, downstairs is where I work’, she told us. When she still lived in the village, the trip from home to the school used to take her and her son one-and-a-half hours. In order to earn an income for her family, He Ying became a migrant labourer in the southern province of Guangdong. During this time, the first of her two children stayed in the village in the care of her mother, who He Ying could only visit once a year. This is the reality for millions of China’s ‘left behind children’73 in the countryside. It is also one of the main reasons that He Ying decided to permanently relocate to Wangjia when the opportunity arose, despite initial opposition from her mother, father, and mother-in-law.

‘Some of the elders came back to the village for a few days and then returned because they didn’t know how to adapt to urban life’, she said. ‘Some don’t know how to cross the street, others don’t know how to take elevators’. As a poor person who relocated, He Ying became a Party leader in the process of lifting herself out of poverty. She now is a leader in the Wangjia relocation community, where she has held the hands of countless elders learning to use zebra crosswalks and ride elevators.

The Party office in the community is decorated with pictures and slogans. On the wall there is a poster that reads ‘The Loving Heart Station’, with photographs showing appreciation of the workers who lead cooking classes, literacy programmes, and cultural activities. Written in big letters is the welcoming phrase: ‘Rest here when tired; drink water here when thirsty, charge your phone here when it’s out of power, heat your food here when it’s cold’. We were waiting to speak with He Ying when an elderly woman walked in and began to ask us how to turn on her gas stove, since she had never owned one before, not knowing that we were just visitors.

Through the All-China Women’s Federation, He Ying is helping build the confidence of newly migrated peasant women to overcome the many challenges they face. Through personal experience, she recognises the difficult transition that people have to make in relocating from the village to the city. In the early months of the relocation, He Ying’s husband grew uncomfortable witnessing his wife’s newfound independence as a leader. However, he has since come around, especially after witnessing the community mobilisation during the fight against COVID-19.

‘I told [the local women] that women could hold up half the sky’, He Ying said. ‘If they could work, they would get more respect from their husbands and alleviate the [financial] burden on their families’. He Ying’s family of ten, which used to live in an 80-square-metre house together, now lives in three spacious apartments totalling 200 square metres. They live in a community with three well-equipped and well-staffed kindergartens, one elementary school, and one middle school. There are two community health centres within a five-minute walk. Though He Ying’s mother is still not adapted to urban life, and perhaps may never be, she is finding her way: ‘Gradually, I’m getting used to the new life here. At least I can cook meals for the kids’, she told us.

He Ying shows us a video on her cell phone of her mother leading a line of children behind her, all seven grandchildren in one place. One of them is He Ying’s elder son, who she had to leave behind to her mother’s care when she was a migrant worker. He is now studying elevator maintenance at a vocational school in the city. ‘I hope that after graduation, he can come back and work in our community to serve the people’, she tells us. She says that technicians are needed to maintain the community’s sixty-four elevators that so many families are just learning to use for the first time.

He Ying has photographs on her phone of her old dilapidated wooden home in the village. She speaks about the village with a sense of loyalty, but without romanticism. ‘I’ll bring my children back to my old village so that they can remember the life of yesterday and cherish the life of today’.

Acknowledgements

This study was led by Tings Chak (翟庭君), Li Jianhua (李建华), and Lilian Zhang (张丽萍).

Xiang Wang (photography) and Daniela Ruggeri (illustration).

Endnotes

- ↩ ‘Xi Declares “Complete Victory” in Eradicating Absolute Poverty in China’, Xinhua, 26 February 2021, www.xinhuanet.com

- ↩ United Nations Secretary-General, ‘Helping 800 Million People Escape Poverty Was Greatest Such Effort in History, Says Secretary-General, on Seventieth Anniversary of China’s Founding’, United Nations Press, 26 September 2019, www.un.org

- ↩ United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, The Sustainable Development Goals Report 2020, July 2020, unstats.un.org; United Nations Development Program, Assessing Impact of COVID-19 on the Sustainable Development Goals, December 2020, sdgintegration.undp.org

- ↩ United Nations Development Program, Impact of COVID-19 on the Sustainable Development Goals, December 2020, sdgintegration.undp.org

- ↩ Mao Zedong, ‘The Chinese People Have Stood Up!’ (21 September 1949) in Selected Works of Mao Tse-Tung: Volume V (Beijing: Foreign Languages Press, 1961). www.marxists.org

- ↩ Zhao Hong, ‘China’s Contribution and Loss in War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression’, CGTN, 13 August 2020, news.cgtn.com

- ↩ John Ross, China’s Great Road: Lessons for Marxist Theory and Socialist Practices (New York: 1804 Books, 2021), 86.

- ↩ Communist Party Member Net 共产党员网, ‘Dang zai 1949 nian zhi 1976 nian de lishi xing juda chengjiu’ 党在1949年至1976年的历史性巨大成就 [The Party’s historic great achievements between 1949 and 1976], 28 July 2016, fuwu.12371.cn

- ↩ Wang Sangui, Poverty Alleviation in Contemporary China, trans. Zhu Lili (Beijing: China Renmin University Press, 2019), 51.

- ↩ Phoenix News 凤凰网, ‘1949–1947 nian: Maozedong shidai zui you jiazhi de lishi yihan’ 1949―1976年:毛泽东时代最有价值的历史遗产, [1949-1976: The most valuable heritage of the Mao Zedong Era], 28 December 2009, news.ifeng.com

- ↩ Maurice Meisner, Mao’s China and After: A History of the People’s Republic (New York: Free Press, 1986), 437.

- ↩ Meng Yaping, ‘Fantastic Feats of China’s Space Odyssey’, CGTN, 19 April 2017, news.cgtn.com

- ↩ Deng Xiaoping, ‘Building a Socialism with a Specifically Chinese Character’ (30 June 1984) in Selected Works of Deng Xiaoping, Volume III (1982-1992) (Beijing: Foreign Languages Press, 1994), en.people.cn

- ↩ Ross, China’s Great Road, 57.

- ↩ The State Council Information Office of the People’s Republic of China, Poverty Alleviation: China’s Experience and Contribution (Beijing: Foreign Languages Press, April 2021), www.xinhuanet.com

- ↩ Singh, Anoop, Malhar S. Nabar, and Papa M. N’Diaye, China’s Economy in Transition: From External to Internal Rebalancing (International Monetary Fund, 7 November 2013), www.elibrary.imf.org

- ↩ Xi Jinping, ‘Secure a Decisive Victory in Building a Moderately Prosperous Society in All Respects and Strive for the Great Success of Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for a New Era’, China Daily, 18 October 2017, www.chinadaily.com.cn

- ↩ United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, ‘Poverty eradication’, Sustainable Development, accessed 30 June 2021, sdgs.un.org

- ↩ ‘Three Regions’ refers to the Tibet Autonomous Region; the Tibetan areas of Qinghai, Sichuan, Gansu, and Yunnan provinces; and Hetian, Aksu, Kashi, and Kizilsu Kyrgyz in the south of Xinjiang Autonomous Region. ‘Three Prefectures’ refers to Liangshan prefecture in Sichuan, Nujiang prefecture in Yunnan, and Linxia prefecture in Gansu.

- ↩ CCTV中国中央电视台, ‘Zhongguo xianxing fupin biaozhun diyu shijie biaozhun? Guojia xiangcun zhenxing ju zheyang huiying’ 中国现行扶贫标准低于世界标准?国家乡村振兴局这样回应 [Is China’s current standard for poverty alleviation lower than the global standard? A response from the National Revitalisation Bureau], 6 April 2021, news.cctv.com

- ↩ United Nations Development Programme and Oxford Poverty and Human Development Initiative, Charting Pathways Out of Multidimensional Poverty: Achieving the SDGs, July 2020, hdr.undp.org

- ↩ World Bank, Poverty and Shared Prosperity 2020: Reversals of Fortune, 2020, openknowledge.worldbank.org

- ↩ New China Research, Chinese Poverty Alleviation Studies: A Political Economy Perspective (Xinhua News Agency, 22 February 2021), www.xinhuanet.com

- ↩ Zhang Zhanbin et al., Poverty Alleviation: Experience and Insights of the Communist Party of China (Beijing: The Contemporary World Press, 2020), 139.

- ↩ New China Research, Chinese Poverty Alleviation Studies, 60.

- ↩ New China Research, Chinese Poverty Alleviation Studies, 77.

- ↩ ‘CPC membership grows to over 95 million’, CGTN, 30 June 2021, news.cgtn.com

- ↩ The State Council Information of the People’s Republic of China, Poverty Alleviation: China’s Experience and Contribution (Beijing: Foreign Languages Press, 2021), 35.

- ↩ The State Council, Poverty Alleviation, 48.

- ↩ The State Council, Poverty Alleviation, 35.