Yukon River chum salmon, which make up 70 percent of the subsistence harvest in the region, didn’t turn up this year. Neighbors are helping out but people worry about hunger in the coming winter.

It’s as if emergency food supplies had to be delivered–beef to Oklahoma, wheat to North Dakota, or apples to Washington state–due to a sudden plunge in harvest levels after thousands of years of plenty. And no one knows why the crops or animal populations failed.

“It’s devastating. And it’s scary,” said Executive Director Serena Fitka, Yup’ik, of the Yukon River Drainage Fisheries Association. “Because we don’t know what is going on with this fish. Why isn’t it coming back?” The association serves 42 Alaska communities on the Yukon River.

Salmon are born in fresh-water streams and rivers then go to sea to mature. They return years later to the waters of their birth to spawn a new generation then die.

A report by Catherine Moncrieff describes the importance of the annual return of salmon to subsistence, the harvesting and sharing of food that’s at the heart of Alaska Native cultures. For thousands of years, the Athabascan, Yup’ik, and Inupiaq people living on the Yukon and its tributaries have depended on salmon as a reliable source of healthy, nutritious food.

Thousands of Alaska Natives customarily spend days or weeks every summer harvesting and preserving fish. Commercial fisheries also provide cash income in regions where jobs are scarce, injecting tens of millions of dollars into local economies.

“I grew up fishing the Yukon and to me it’s near and dear to my heart,” Fitka said.

I’m very passionate about serving our people, and really very passionate about making sure that not only that people have fish on the table through the winter, but also it’s about the cultural identity because our traditions, our values are so ingrained in how we prepare our food.

People jar cases of plain and smoked salmon, some flavored with spices and jalapeno peppers, store dried fish, and fill their freezers with salmon steaks, fillets, or whole salmon. Usually their stash of salmon lasts until spring. It’s a dietary staple, in part because the villages are accessible only by boat or plane. Transportation costs drive up prices to a third more than or even double the U.S. average.

“These communities are remote,” Fitka said.

The cost of living is very high and I would rather be able to go get my moose or get my fish for the winter instead of buying a $100 three-pound roast from the store.

An empty fish rack in St. Marys, a village on the Yukon River, at a time of year when it would normally be packed with salmon fillets getting smoked or dried for preservation (Photo by Serena Fitka, Yukon River Drainage Fisheries Association). 2021

This year, there are no nets in the water, no fish wheels scooping up salmon, the most effective ways to fish in quantity. Many people are still visiting their tent or cabin at fish camp to harvest alternative species, in a labor-intensive effort to make up for the loss.

But it’s a big gap to fill. Chum salmon, one of five species of salmon, makes up 70 percent of the subsistence harvest. Chum numbers have been declining for decades. In 1918, a million chum were harvested just to feed sled dogs. From 1987 to 1991, an average of 1.1 million chum were harvested in the fall fishery, and another 384,000 in the spring.

This year fewer than 300,000 chum salmon are predicted to return. That’s not enough to sustain the chum salmon population, much less allow a harvest, so commercial and subsistence fisheries are closed.

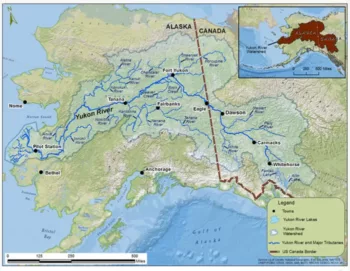

The Yukon’s headwaters, 900 miles of the river, are in Canada. Under the terms of a treaty, the United States is obligated to allow 500,000 chum salmon to cross into Canada. Returns this year are too low to meet that obligation.

Fitka said it was sad to visit her home village of St. Marys earlier this summer.

I want to be on the river and I want to take my kids out. I want them to learn how to cook and prepare our food traditionally. And that was how it was in every community on the river. It was very depressing. I traveled this summer, I was able to travel to a lot of communities and they felt the same way. They said, ‘I feel depressed.’

“Yukon River families want to raise their children with knowledge of fishing and experiences growing up at fish camps teaching them knowledge, skills, and abilities that are critical to surviving life in rural Alaska,” reads Moncrieff’s report.

The Yukon River is the longest undammed, free flowing river in the world. And that raises the question: what’s killing the salmon? Biologists and fishermen point to several possibilities:

- Increased predation as other species decline in the North Pacific

- Competition for food by hatchery fish

- Inadvertent harvest on the high seas by trawlers targeting other species

- Warmer ocean and freshwater water temperatures

- Lower freshwater levels

- Scouring of riverbeds by floods of water from rapidly melting snow

Various remedies have been recommended and some put into action. Since the cause for the decline is unknown–and it could be a combination of several factors–it’s hard to figure out the solution.

The Yukon River Drainage Fisheries Association holds a weekly teleconference during the fishing season for fishermen and fisheries managers. Fisheries consultant Dennis Zimmerman, of Whitehorse, on a recent call, said,

It’s clear everyone’s hurting. What I’ve heard a few times is, the system isn’t working. We can’t keep doing the same thing over and over again.

He said it’s important that the scientific work by the Canadian Department of Fish and Oceans, and the Alaska Department of Fish and Game continues.

Where residents usually fish with nets to catch fish in quantities, a couple uses rods and reels to harvest non-salmon species at the mouth of the Melozi River, a tributary on the Yukon river. (Photo by Serena Fitka, Yukon River Drainage Fisheries Association).

“We probably are not going to find the silver bullet,” Zimmerman said. He supports using (Canadian) Research and Enhancement funds “for ways to adapt to keep kids cutting fish, using ceremonial fish, and going to alternative species. Keep those cultural elements alive with the few fish we’ve got. No one gains from a lost culture,” he said.

The Association of Village Council Presidents, which represents 56 villages in the Yukon-Kuskokwim region, announced on July 22 there hasn’t been enough fish for people to stock up for the winter but neighbors have stepped up to help.

A neighbor-to-neighbor gift

South of the Yukon River on the coast, Bristol Bay this year had its largest sockeye salmon run ever: 63 million fish, well above the Alaska Department of Fish and Game forecast of 50 million.

The six fish processors operating in Bristol Bay voted on July 1 to donate 25,000 pounds of salmon to Yukon River communities.

The village council presidents association said “an amazing number of organizations” pulled together to get the fish delivered. The nonprofit Seashare is coordinating the effort. They’re working with airline companies, regional nonprofits, fisheries developers, and tribes. The state covered some costs but most were donated.

Delivery to villages along both the upper and lower Yukon river began in late July. Tribes in the villages decided how to hand out the fish, with the first deliveries going to elders.

Gov. Mike Dunleavy announced Tuesday the state is using some of its COVID fiscal recovery funds to get another 12,500 pounds of fish delivered to lower Yukon River villages. That batch was purchased from Copper River Seafoods.

“We are grateful to Governor Dunleavy and all involved for the donation of salmon to the communities on the Lower Yukon River in a time of need,” said CEO Vivian Korthuis, Yup’ik, Association of Village Council Presidents.

Again, the donation will not fill the freezers up, but the salmon is very appreciated. We are grateful and acknowledge the teamwork it took to get the salmon from where they were caught, transported, delivered and distributed to the families along the Lower Yukon River. Quyana (thank you in Yup’ik) on behalf of the region.

Dunleavy said additional deliveries will be announced in coming weeks.

Joaqlin Estus, Tlingit, is a national correspondent for Indian Country Today. Based in Anchorage, Alaska, she is a longtime journalist. Follow her on Twitter @estus_m or email her at [email protected].