As was detailed in Part 1 of this series, the “epic” battle being waged, or rather being reported on in the corporate entertainment press, is between streamers and theatres or between various streamers.

However, this is a battle now being fought not just in the U.S.–Netflix is already losing U.S. subscribers to its rivals Disney+ and HBO Max–but throughout the world. Only through global subscriptions can these companies, most of whom have run up huge debts, stay one step ahead of their creditors. It is also through global profits that the companies, most now flush with cash but with the pressure of debt and increased competition always looming, can outmanoeuvre any single country that attempts to compete, a situation I detail in my new book Diary of a Digital Plague Year: Corona Culture, Serial TV and The Rise of The Streaming Services.

In the U.S. these companies are private, but in the rest of the world complicated systems of financing of film and television, and increasingly as well of alternative streaming services, usually feature a healthy amount of government funding. This funding in many cases helps account for more progressive and socially concerned films and programmes.

Neoliberal capitalist corporations vs. national governments and creatives

So this battle for the soul of popular media is actually between neoliberal, utterly profit-driven conglomerates against national governments and individual creatives who are attempting to retain some shred of their own culture and potentially address problems endemic to them.

More and more though, the power of the American streamers is forcing national films and television series to dilute their content. This is in order to also reach a global audience which they now also increasingly need, in order to compete.

This global sweep is now the main profit-making element of Netflix, where foreign subscribers now outnumber those in the U.S. and which is available in 190 of the 195 countries in the world. There are limits though even for the most dominant streamer which must come up with new content and which does not have an extensive back catalogue of films and series as do the other streamers, most of which have merged with Hollywood studios so that they now contain studio offerings going back decades.

Netflix panicked during the production halt in last year’s confinement and began leasing or buying older films such as the Francois Truffaut collection, as well as now constantly needing to compete with the other streamer/studios by corralling topline stars and directors into its stable. For example, as it has done with the upcoming Don’t Look Up, directed by The Big Short’s Adam McKay and starring Leonardo DiCaprio, Jennifer Lawrence and every other Hollywood newcomer and star they could round up.

These limitations aside, Netflix and the other American streamers following in their wake are adept at outmanoeuvring local producers and governments, with examples abounding in Britain, Italy, Australia and Spain.

In Britain, where the steamers Britbox–a combination of the programming of British public and private channels–and BFI Player attempt to counter this influence, Netflix early in its run employed in Britain 900 engineers, a huge number and comparatively, in terms of Europe, “more than any channel in France can mobilize.”

British regulators are also incensed about a Netflix button on the standard remote control of any television so that viewers can bypass British public television and go straight to streaming.

In Italy, the government is watching its industry be undermined due to its extremely generous 30 percent tax rebate for programme-making by streaming services, which results in some temporary creation of jobs but no sharing of residuals. The Italian pay on demand channel Chili is now giving Apple iTunes a run for its money in Italy, but partly because it has cash from the U.S. rivals Warner Brothers, Fox and Disney, who are attempting to outflank Apple.

Australia, which has a vibrant public television network, is being outspent by Netflix by almost 10 times as much ;in 2020 $841 million to $89.7 million. The country is in danger of being swamped by the streamers, as TV stations collapse due to loss of advertising revenue. Consumers early on demonstrated an appetite for turning off public television already in place as, before Netflix legally entered the country, 23 percent of the country, 6 million out of a total of 23 million, watched the service using VPNs which conceal the viewing country. Australia also boasts a rival streaming service, Stan, but forecasts that it too will soon be overtaken by Disney+, which has only been operating in the country for two years.

Money Heist, a Netflix global hit Perhaps the major battle is being fought in Spain, which Netflix has made its European capital. The country has abundant sunshine for filming outdoors, talent from an already developed industry, and the streaming service sees it as a portal by which it will be able to access Latin America and the 580 million Spanish speakers in that world. As Screen International reported, Netflix currently lists 50 Spanish titles, led by one of the world’s most popular series Money Heist which will is forecast to return for its final season in September.

The streamer currently boasts 70 film productions with 35 Spanish partners and claims to have created 1500 jobs for cast and crew and to supply 21,000 days of work for extras. The country is a production site not only for Spanish series but also Anglo series like The English, an Amazon epic Western with A Quiet Place’s Emily Blunt, as other streamers also recognize Spain’s value as a location that is exotic but cheaper than the U.S.

The country though may be in danger of being overwhelmed. Netflix produces more content than is even required of it by the government and its so-called job creation is all temporary, with again fees paid upfront and Netflix then owning the work in perpetuity.

Government attempts to stem the tide

Governments and national film and television industries are beginning to realize that their own films and series will be swept aside if this onslaught continues unabated. In Australia, there is now an attempt to address the imbalance whereby the local streamer Stan is required to give over half of its time to Australian programming, but the foreign global streamers are under no such restriction.

One proposal would require that any streamer with over 500,000 subscribers invest 20 percent of its profits in the Australian film and television industry. That proposal is being resisted, even by some Australian academics, claiming that the investment might instead open the way for a more globalized Australian content, a spurious “international free market” argument aimed at granting the American streamers full power.

In Spain, like everywhere else, the challenge is to keep the industry from becoming what Screen labels “a service industry for the U.S. giants.” There is now a law requiring streamers to pony up 3.5 percent of their profits for investment in the Spanish TV industry and 2 percent in the film industry. In addition, a bill expected to be passed next year by the Socialist government will require 1.5% of streaming revenue to be earmarked to finance Spanish public television.

South Korea, the Asian leader in television series, in attempting to withstand a Netflix investment in the industry of $500 million, wants to charge Netflix “network fees” so that they contribute to supporting local television.

France has perhaps the most extensive system of protection, but still seems stuck in the cinema model onl, y since none of its films were released to streamers during the year-long lockdown and now have come barreling into cinemas at the same time as new restrictions, including a 50-person maximum per screen limit.

The country has the largest investment requirement and is currently negotiating with Netflix asking for 25 percent of its French revenues to be re-invested in French production along with the Netflix upfront one-time payment being replaced by rights sharing. In return the country would relax its three-year restriction of a Netflix film in the cinemas and allow Netflix films to play on television after one year.

The European Union as a whole is also trying to stem this tide by advancing funds to “foster real European productions” and this now includes supporting pan-European streaming platforms. The EU advanced $2.6 billion in the last 30 years and practically matched that total amount in May of this year by allocating $2.4 billion. The idea is to promote cross-border circulation featuring “European culture and linguistic diversity”, by becoming a promoter with the scale to compete and to break down national fragmentation.

Part of the strategy is also to force the American streamers to invest in smaller, Eastern European countries, which are largely fed content from the Western states. The danger is that producers eying this money will lose focus on the local specifics which make their films and shows socially and politically relevant.

A national fund that is also sponsoring socially inflected filmmaking is the Doha fund from Qatar, a country much maligned by Saudi Arabia for its economic ties to its neighbor Iran. At the last Cannes festival, the fund contributed to two of the most socially aware films in the festival. These were The Gravedigger’s Wife, about the lack of medical treatment in Somalia and a disguised call for universal health care, and Amparo, about a mother’s attempt to keep her son from being strongarmed into the military in Colombia in the 1990s in Medellin, with echoes across the decades of the protests in that city today.

On the other hand, government funding and participation may also be used to conceal repression. Saudi Arabia, in contrast to the United Arab Emirates’ attempt to diversify its source of revenue, is doubling down on oil. This is even as the globe reels from the effects of greenhouse gases, the main source of which is fossil fuels, as it alternates between floods, droughts and ever more destructive and all-consuming fires.

The kingdom is using the film industry as greenwashing, as a sign of its modernization and liberalization. Mohammed Bin Salman, infamous for his devastation of Yemen, one of the poorest countries in the world, and for the Khashoggi assassination, lifted a ban on cinemas in the country in 2017, with screens increasing from 300 in that year to an expected growth of 2,500 by 2030, making it the only country in which box office returns grew in 2020.

A $10 million film fund supports film projects throughout the Arab world and Africa, with the country also boasting its own streaming service Shahid VIP, but also not being above fairly ruthless competition. Egypt has been the main outlet for films from this burst of Saudi financing, but the kingdom scheduled its entrée into the international film world–The Red Sea Film Festival–in December at the same time as the Cairo film festival.

The West, which initially refused Saudi money with the producing agency Endeavor famously returning $400 million after the Istanbul assassination, while always creeping around the Saudi tent, is now coming back through the front entrance. For any film festival to succeed it needs a prominent director, and the Saudis enlisted Edward Waintrop, the head of the Cannes Director’s Fortnight section, whose rationale for lending credibility to a warlike regime that is helping to devastate the planet was that this festival would be celebrating filmmaking as [a] force for positive change.”

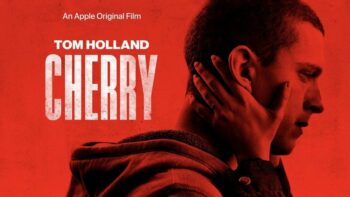

Hollywood, since the Saudis have too much money for the industry to retain its integrity for long, is now back in force with this year’s Cherry, a Russo Brothers (The Avengers) film for Apple with Spiderman’s Tom Holland. The Saudi film fund also invested in Disney last year as well as pouring $50 million into the Russo brothers production company, thus putting it on the entertainment industry map.

Finally, governments may also promote regulation designed primarily not to halt the economic swamping of the industry but to upend any attempt at criticism. This is the case in India, with the right-wing Modi government’s highly repressive broadcasting code which forbids all content that “disrespects the sovereignty and integrity of India,” is “detrimental to India’s friendly relations with foreign countries” and “endangers national security.”

The code has been used to attack both Netflix and Amazon, both of which have featured films and series that spotlight the neoliberal turn in the country toward a regressive and divisive social system. Amazon’s series Tandav, first broadcast at the time of the farmers’ strike in Delhi, opens equally with a farmers’ strike being brutally suppressed by smiling, rotund police and then details the ruthless, murderous rise of a politician who has no scruples and hides behind a supposedly religious code, in a Modi-like fashion. Netflix’s White Tiger, based on a popular novel, is a reverse Slumdog Millionaire, where a poor boy learns the cunning and ruthlessness it takes to come out on top in Modi’s society, in a kind of Scorsese-esque Wolf of Wall Street treatment.

Both challenge the law and both were attacked under it, making this the rare case where the streamers, chasing new subscribers through a sensational expose, contributed to a progressive conversation about a repressive, right-wing government.

So what is to be done?

In one sense the streamers and their attack on the last vestiges of socially responsible film and programme making and on media sovereignty are the ultimate expression of the neoliberal ethos. Neoliberal capitalism is plundering the world, increasing equality, poverty and wage precarity, with weakened governments now barely able to react, let alone influence, plan and control the global economy in any meaningful way.

So, what is the answer? We need a re-organization of civil, social and governmental society in which the natural tendency of creators, supported by governments and thus freed from the dreadful imperative of the profit motive, can flourish as they have the space to look around them and put on display the ravages of this system.

For the moment this exists only in dribs and drabs and incomplete pieces, such as Mike White’s critique of ruling-class nonchalance in The White Lotus or Taika Waititi’s more open acknowledgement of the humour and pathos of Native American life in Reservation Dogs. Any truly creative, social movement must acknowledge the power of the media of film and Serial TV and encourage its truth telling rather than its addictive qualities. In the end speaking truth to wealth and power is the most effective alternative to the kind of corporate palliatives that, despite the ever-worsening situation which threatens us all, still go under the misnomer “entertainment.”

Dennis Broe’s latest book is Diary of a Digital Plague Year: Coronavirus, Serial TV and The Rise of The Streaming Services. He is also the author of Birth of the Binge: Serial TV and The End of Leisure. His TV series blog is Bro on The Global Television Beat. His radio commentary can be heard on his show Breaking Glass on Art District Radio in Paris and on Arts Express on the Pacifica Network in the U.S. He is the author of two novels: Left of Eden, about the Hollywood blacklist and A Hello to Arms, about the postwar buildup of the weapons industry. He is currently teaching in the Masters’ Program at the Ecole Superieure de Journalisme. He is an arts critic and correspondent for the Morning Star and for Crime Time, People’s World and Culture Matters, where he is an Associate Editor.