Each generation must, out of relative obscurity, discover its mission, fulfil it, or betray it.

– Frantz Fanon1

When you are in Greyville, a neighbourhood in Durban in KwaZulu-Natal, you might look up at a building that bears the following signage: 86 Charlotte Maxeke Street, Ultra Kidney Care Renal Dialysis Unit. There is no indication that where this modern structure stands today is a historic site that was of political prominence in the 1970s. This used to be a building that housed the national office of the South African Students’ Organisation (SASO), founded in December 1968, the Natal Youth Organisation (NYO), founded in 1972, and the founding office of the Black Community Programmes (BCP), created the same year. This site holds a history that continues to inspire activists today. Charlotte Maxeke Street–formerly known as Beatrice Street–was named after the first president of the Bantu Women’s League (BWL), which Maxeke founded in 1918 (though, in practice, both names are used interchangeably).

The community building and political organising that took place at 86 Charlotte Maxeke was a continuation of a tradition that had long existed on this street. In the early twentieth century, the building had been a McCord Hospital Dispensary, a pioneering health centre for Black people. Down the street at number 29 is the Beatrice Street Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA), which was once the Bantu Social Centre, an institution with its own rich history. Created in 1933 as an arts and sports centre, the Bantu Social Centre played a central role in mobilising Black resistance to apartheid and was home to the first library for Black people in the region–despite its origins to pacify the oppressed by providing them with a genteel, non-political space for recreation. Like later Black Consciousness institutions, the Bantu Social Centre’s character became more political over time, subverting the mission of its origins. From the 1940s onwards, it bridged social life and politics. When the famous anti-apartheid Defiance Campaign of 1952 was launched in Natal, the Bantu Social Centre was its base. Number 90 is still the home of the famed United Congregational Church of Southern Africa, known as Ezihlabathini (meaning ‘in the sands’), which has served as a meeting space for Black people since 1891.

The neighbourhood was an important hub for Black social, political, educational, and economic life in the heart of the city’s busy trading and working-class area. It was a landing pad for migrant workers from rural areas, a melting pot where different people mixed: blue collar workers, street traders, shop owners, hustlers, entrepreneurs, entertainers, and educators of many religions, cultures, and traditions.

This dossier focuses on the Black Community Programmes (BCP), a series of projects initiated in 1972 that served as the practical implementation of the Black Consciousness philosophy to give Black people the power to become self-reliant. In practice, these programmes included the foundation of publications and research, health centres, factories to employ the economically marginalised, and a trust fund to provide basic necessities for former prisoners as well as grants for yet other projects. In order to understand the BCP, we must understand the context in which it was born. In particular, the Pass Resistance Campaign and the Sharpeville Massacre marked a turning point in apartheid South Africa that set off the birth of the Black Consciousness Movement, which included SASO and the BCP, among others.

The Pass Resistance Campaign

South Africa’s pass laws were a fundamental bulwark of the apartheid system. These laws facilitated the control of Black people in South Africa by the Nazi-inspired, white supremacist National Party (NP) government, which came to power in 1948. The pass laws determined where Black people in South Africa could live and work, and even the kind of employment they could engage in. A pass book contained the details of a Black person’s status: it was similar to an internal passport, with the name of the bearer and their fingerprints, photograph, and address, as well as the name of their employer and whether they were allowed to be in a particular area or city. By 1960, each and every Black South African adult had to carry their pass or reference book at all times. It needed to be instantly presented for inspection when demanded by the police. Failure to produce a pass led to immediate arrest, prosecution, and a fine or jail sentence. Informally, passes were often called dompas–meaning both ‘dumb pass’ and ‘domestic passport.’

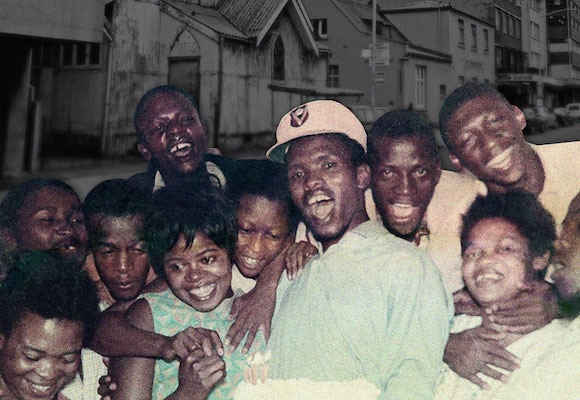

The Bantu Social Centre (now Beatrice Street YMCA) at 29 Beatrice Street in Durban, 1953.

(Source: Durban Local History Museums)

On 16 March 1960, Robert Sobukwe, the president of the Pan Africanist Congress (PAC) which was founded in April 1959, wrote to Major-General C.I. Rademeyer, the commissioner of police:

The Pan Africanist Congress will be starting a sustained, disciplined, non-violent campaign against the pass laws on Monday the 21st March 1960. I have given strict instructions, not only to members of my organisation but also to African people in general, that they should not allow themselves to be provoked into violent action by anyone. … I am now writing to you to instruct the police to refrain from actions that may lead to violence. It is unfortunately true that many white policemen, brought up in the racist hothouse of South Africa, regard themselves as champions of white supremacy… We will surrender ourselves to the police for arrest. If told to disperse, we will. But we cannot be expected to run helter-skelter because a trigger-happy, African-hating young white police officer has given hundreds of thousands of people three minutes within which to remove their bodies from the immediate environment.2

Two days later, on 18 March 1960, Robert Sobukwe announced at a press conference in Johannesburg that the Anti-Pass Campaign would be launched on Monday 21 March. Sobukwe stated the following:

I need not list the arguments against the pass laws. Their effects are well known. All the evidence of broken homes, … the regimentation, oppression and degradation of the African, together with the straight-jacketing of industry leads to one conclusion, that the pass laws must go. We cannot remain foreigners in our own land.

I have appealed to the African people to make sure that this campaign is conducted in a spirit of absolute non-violence … I now wish to direct the same call to the police.3

The Sharpeville Massacre and Political Repression

On Monday 21 March 1960, Robert Sobukwe led a mass defiance of South Africa’s pass laws called the Anti-Pass Campaign, also known as the Pass Resistance Campaign or, to use Sobukwe’s words, ‘positive action against the pass laws.’4 Sobukwe urged Black South Africans to leave their passes at home and go to police stations, subjecting themselves to arrest. On that infamous, never-to-be-forgotten day in the township of Sharpeville, near Johannesburg, white South African police gunned down a peaceful crowd of unarmed Black demonstrators. Sixty-nine people were killed and a hundred and eighty were injured. Most of the victims were shot in the back, clearly indicating that they were moving away, yet the police kept firing. Many of the victims were women and children.

This horrific indiscriminate killing, which came to be known as the Sharpeville Massacre, changed the course of South Africa’s history. The widely publicised Sharpeville Massacre confronted the NP government with an unprecedented political crisis. Both in South Africa and internationally, the reaction to the massacre was strident.

In the aftermath of the Sharpeville Massacre, the government became even more ruthless and relentless in dealing with anti-apartheid resistance. On the same day that the Anti-Pass Campaign began, Sobukwe and other national PAC leaders were arrested and later convicted for inciting people to commit an offence in protest against the laws. Sobukwe was sentenced to three years in prison and began to serve his sentence at the Old Fort in Johannesburg. In 1963, the new General Law Amendment Act was passed, allowing Sobukwe’s imprisonment to be renewed annually at the discretion of the Minister of Justice. After serving his three-year sentence, Sobukwe was sent to the notorious Robben Island Prison, where he was confined to living in a separate area and was strictly prohibited from contact with other prisoners.

On 26 March 1960, Inkosi Albert Luthuli, the then-president of the African National Congress (the ANC, originally known as the South African Native National Congress [SANNC] founded in 1912), publicly burnt his pass in Pretoria and invited all Black South Africans to do the same.

On 30 March 1960, the NP government declared a state of emergency, effective for one year, which allowed it to indefinitely detain people it deemed to threaten the regime and seize publications perceived to be subversive. Empowered by the Unlawful Organisations Act No 34 of 1960, the regime banned the PAC and the ANC on 8 April 1960–a direct reaction of the NP to the 1960 Anti-Pass Campaign launched on 21 March, which allowed any organisation deemed to threaten the public order or the safety of the public to be declared as unlawful. Almost immediately, both the PAC and ANC went underground. Subsequently, Umkhonto we Sizwe (‘the Spear of the Nation’) was formed by the ANC and the Congress Alliance as an armed wing during the period of 1961 to 1962. Similarly, between 1962 and 1963, while Sobukwe was in jail, several exiled PAC leaders who were based in Maseru, Lesotho formed the PAC’s armed wing, Poqo (the abridged name for Ama-Afrika Poqo in isiXhosa, meaning ‘the real owners of Africa’ in English).

The banning of the PAC and the ANC had been preceded by the 1950 banning of the Communist Party of South Africa (which later became the South African Communist Party or SACP) through the Suppression of Communism Act of 1950. The Act banned any party or group which subscribed to communism and prohibited ‘certain periodical or other publications’, strengthening political censorship.

The banning of the SACP, the PAC, and the ANC effectively suppressed legal political activity by these parties and many individual activists. Prior to this, the Riotous Assembly Act of 1929 had been one of several measures officially used to control political activists. This had a devastating effect on the possibilities for public life. For example, then-president of the ANC, Inkosi Luthuli, was banned in May 1953 until his death in July 1967, effectively spending about fourteen years in political limbo. Because of the Suppression of Communism Act, some radical anti-apartheid campaigners were detained indefinitely without trial, while others went into exile. The latter group included well-known activists Gertrude Shope, Ruth First, Oliver Tambo, Joe Slovo, Ben Turok, and Duma Nokwe, to mention a few.

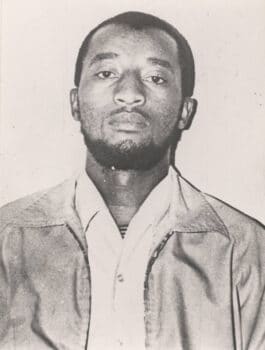

Mapetla Mohapi, the administrator of the Zimele Trust Fund and general secretary of SASO, pictured above, was killed in the Kei Road police station just outside of King William’s Town on 5 August 1976 after a period of detention under Section 6 of the Terrorism Act.

(Source: UNISA Archives)

October 1963 saw the commencement of the now-iconic Rivonia Trial of ten leading anti-apartheid activists facing charges of sabotage. In June 1964, eight top leaders of the ANC and the Congress Alliance were sentenced to life imprisonment: Nelson Mandela, Walter Sisulu, Govan Mbeki, Raymond Mhlaba, Ahmed Kathrada, Dennis Goldberg, Elias Motsoaledi, and Andrew Mlangeni. They were all sent to Robben Island, which imprisoned Black, Indian, and Coloured South Africans, with the exception of Dennis Goldberg, who was sent to Pretoria Central Prison’s section for white political prisoners. From the mid to late 1960s, there were over 1,000 PAC and ANC members and a few activists from other smaller organisations on Robben Island.

Filling the Void: The Birth of SASO

By the mid-1960s, there appeared to be a political lull in South Africa. The fearful climate, tense with political silence, was a result of a harsh clampdown on protests, brutal political killings, and the outlawing of key political organisations. In addition, the persecution of activists through banning orders, detainment without trial, life imprisonment sentences, and exile constrained the anti-apartheid movement. To the National Party, this looked like the defeat of their enemies, at least for a while. But while older people may have seemed cowed by repression, young people gallantly fought back and tried to fill the political vacuum created by the banning of two key political parties that embodied the aspirations of the masses.

Black students who were aligned with the ANC formed the African Students’ Association (ASA) in 1961, and Black students affiliated with the PAC formed the African Students Union of South Africa (ASUSA) in 1962. However, these organisations were operational only for a short time because associating with banned organisations was risky and university management was hostile to student political groups.

The establishment of SASO in 1968, followed by the creation of the BCP in 1972, was a response to the political vacuum during this period. SASO initially emerged in response to Black students’ marginalisation in white-dominated educational institutions. From 1963 to 1964, many Black students had joined the multiracial National Union of South African Students (NUSAS), founded in 1924. Members of NUSAS, mainly from white English-speaking universities, fought against apartheid. But NUSAS operated in a deeply segregated educational system.

In 1967, Steve Biko, a medical student at the University of Natal Non-European section in Wentworth, attended the NUSAS conference at Rhodes University in Grahamstown (now Makhanda) that July on behalf of the Wentworth campus. The following year, in 1968, he attended a conference of the multiracial University Christian Movement (UCM) in Stutterheim in the Eastern Cape. UCM, created in 1966 and 1967 and led by Protestant Minister Basil More and Catholic Priest Colin Collins, was supported by many Black students. At the UCM conference, Biko began to drum up support for the idea of an all-Black students’ movement, which would do away with the difficulties of symbolic integration and white liberal leadership. Many Black students within UCM reacted positively to Biko’s suggestions.

Biko organised a formal meeting of Black student leaders to discuss the launching of a new movement exclusively for Black people in December 1968 at his alma mater, St Francis College, a Catholic mission school in Mariannhill, outside of Durban. The meeting was attended by approximately thirty Black members of university Students Representative Councils (SRCs). The SRC members reacted enthusiastically to the idea of an all-Black organisation, and it was agreed that it would be named SASO.

In July 1969, the inaugural conference took place at the University of the North (also known as ‘Turfloop’ and currently the University of Limpopo). Biko was elected SASO’s first president. The founding cohort was made up of:

- Barney Pityana, an exponent of Black theology who succeeded Biko and became the second President of SASO in July 1970 at the first General Students Council of SASO.

- Harry Ranwedzi Nengwekhulu, who was elected permanent organiser when SASO was founded.

- Petrus Machaka, the first vice president of SASO, elected at the inaugural conference in July 1969.

- Manana Kgware, who was elected secretary of SASO at the inaugural conference in July 1969.

- Vuyelwa Mashalaba, who was also elected secretary of SASO at the inaugural conference in July 1969.

- Strini Moodley, a student at the University College for Indians, Salisbury Island, Durban, which was the precursor to the University of Durban Westville. He wrote the famous political satire Black on White and was also the editor of the SASO Newsletter.

- Aubrey Mokoape, who was present at the formation of the PAC as a teenager in 1959. Influenced by Sobukwe, he participated in the 21 March 1960 anti-pass campaign and was arrested for his involvement. At the age of sixteen, he was South Africa’s youngest political prisoner at that time. After serving three years in prison at the Old Fort’s Number Four prison complex in Johannesburg, he enrolled in the University of Natal Non-European section in Wentworth, Durban, where he was a student at the same time as Biko.

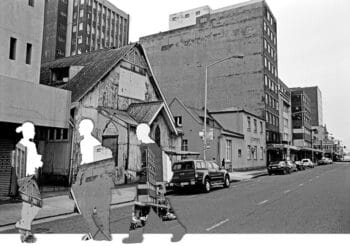

The United Congregational Church of Southern Africa (Ezihlabathini) at 90 Beatrice Street is featured second from the right with the slanted roof; to its left is the since-demolished head office of Black Community Programmes and an office of the South African Students Organisation.

(Source: Durban Local History Museums)

At the 1st General Student Council of SASO in July 1970, Biko was elected chairman of SASO’s publications. The debut issue of the monthly SASO Newsletter was launched in August of the same year. This important publication carried a regular column by Biko under the pen name Frank Talk entitled ‘I Write What I Like.’ By 1972, the circulation of the SASO Newsletter had reached 4,000 readers. As Frank Talk, Biko wrote:

It will not sound anachronistic to anybody genuinely interested in real integration to learn that blacks are asserting themselves in a society where they are being treated as perpetual under-16s. One does not need to plan for or actively encourage real integration. Once the various groups within the given community have asserted themselves to the point that mutual respect has to be shown, then you have the ingredients for a true and meaningful integration. At the heart of true integration is the provision for each man [and woman], each group to rise and attain the envisioned self.5

The Black Consciousness Movement

SASO advocated the ideology of Black Consciousness. As Biko wrote in his famous essay ‘Black Consciousness and the Quest for a True Humanity’, ‘Black Consciousness is an attitude of mind and a way of life, the most positive call to emanate from the black world for a long time.’6 From SASO’s inception, Biko and his colleagues agreed that the oppression of Black people was a psychological problem. The struggle for SASO was to make Black people halt their dependence on white people. SASO maintained that most Black people had been subjugated for such a long time that, psychologically, they were not even aware of their oppressed state. In SASO’s view, because of centuries of European cultural imperialism, most Black people suffered from an inferiority complex. Hence, Biko wrote: ‘At the heart of this kind of thinking is the realisation by blacks that the most potent weapon in the hands of the oppressor is the mind of the oppressed.’7 He defined Black Consciousness as an ideology that:

seeks to give positivity in the outlook of the black people to their problems. It works on the knowledge that ‘white hatred’ is negative, though understandable, and leads to precipitate and shot-gun methods which may be disastrous for black and white [people] alike. It seeks to channel the pent-up forces of the angry black masses to meaningful and directional opposition basing its entire struggle on realities of the situation. It wants to ensure a singularity of purpose in the minds of the black people and to make possible total involvement of the masses in a struggle essentially theirs.8

Membership of SASO and the Black Consciousness Movement also included Coloured and Indian South Africans. Biko’s definition of Blackness was expansive:

We have in our policy manifesto defined blacks as those who are by law or tradition politically, economically and socially discriminated against as a group in South African society … identifying themselves as a unit in the struggle towards the realisation of their aspirations. … Merely by describing yourself as black, you have started on a road towards emancipation.9

In Biko’s words, SASO’s position was essentially that ‘blacks are tired of standing at the touchlines to witness a game that they should be playing. They want to do things for themselves and all by themselves.’ Thus, the organisation aimed ‘to crystalise the needs and aspirations of non-white students and to seek to make their grievances known.’10

Some observers saw Black Consciousness as ‘reverse racism.’ On this view, Biko wrote that ‘We are looking forward to a non-racial, just and egalitarian society in which colour, creed and race shall form no point of reference.’<11 This was similar to the idea of Black leadership geared toward a non-racial society advocated by Sobukwe and Luthuli.

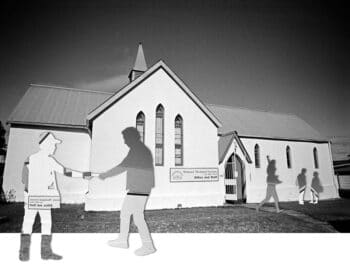

15 Leopold Street, where the Eastern Cape Black Community Programmes and South African Students Organisation office was located in King William’s Town (eQonce).

(Source: Steve Biko Foundation)

Biko and the other founders of the Black Consciousness Movement in South Africa were inspired by a global moment of Black self-assertion and the works of a range of radical writers of the time. Among them were Frantz Fanon’s Black Skin, White Masks and The Wretched of the Earth, Aimé Césaire’s Discourse on Colonialism, John Mbiti’s Introduction to African Religions, Eldridge Cleaver’s Soul on Ice, C.L.R. James’s The Black Jacobins, Stokely Carmichael and Charles Hamilton’s Black Power: The Politics of Liberation, and The Autobiography of Malcom X. Key concepts and ideas were triggered by thinkers such as Charles Hamilton, James Cone, Cheikh Anta Diop, David Diop, Léopold Senghor, and Kenneth Kaunda as well as frameworks such as négritude and African humanism. Further stimulus flowed from the U.S. civil rights movement of the late 1950s and 1960s, such as the Black Panther Party and the Montgomery Bus Boycott of 1955.

Black Community Programmes

The BCP were founded in 1972 in response to the need to address community welfare, culture, Black theology, education, literacy, Black art, self-help, and other relevant projects. The BCP outlined its goals ‘To help the Black Community become aware of its own identity… [and] create a sense of its own power. To enable the Black community to organise itself, to analyse its own needs and problems and to mobilise its resources to meet its needs. To develop Black leadership capable of guiding the development of the Black community.’12

Historian Leslie Hadfield maintains that, during the early years of the 1970s, proponents of Black Consciousness expanded their notion of ‘development’ to ‘a kind of community development designed to bring about a social and then eventual political liberation.’ This notion manifested in the creation of a series of concrete projects through the BCP. The Black Consciousness Movement’s objective was to galvanise Black society at all levels so that they would recognise and co-operatively realise their self-sufficiency and ‘attain the envisioned self’ through the BCP, as Biko wrote.13

Black Consciousness stalwart Mamphela Ramphele aptly pointed out that the development goals of the Black Consciousness Movement through the BCP:

were articulated as the practical manifestation of Black Consciousness philosophy, which not only called for critical awareness of social relations amongst the oppressed, but for the need to translate that awareness into active programmes for liberation from white domination.… It was argued that people who had known nothing but scorn and humiliation needed symbols of hope to lift them out of despair and to empower them to liberate themselves.14

The underlying message of the BCP was that a community cannot be self-reliant unless it is aware of and proud of its identity and dignity. A community cannot be self-reliant unless it has power (which manifests itself in the existence of institutions and organisations that make collective decisions concerning the community’s destiny). A community cannot be self-reliant unless it uses its resources–material, physical, mental, and spiritual–effectively for its own benefit. A community also cannot be self-reliant unless it has adequately trained leadership to guide the development of its members.

Mamphela Ramphele wrote about how Black Consciousness activists were heavily influenced by their involvement in the field of community development, especially by two main forces. First, by the ideology of ujamaa as a development philosophy promoted by President Julius Nyerere of Tanzania, which in Ramphele’s words, ‘sought to utilize traditional structures of the economy of affection for national development.’15 Second, she wrote that ‘Paulo Freire’s conscientisation approach in Latin America was found to have great relevance for the problems [Black Consciousness] leaders identified amongst black people in South Africa.’16

Christian institutions also played a fundamental role in the formation of BCP that stemmed from Beyers Naudé’s Christian Institute.17 The Study Project on Christianity in Apartheid Society–Phase 2 (SPRO-CAS 2), from which the Black Community Programmes developed into an independent organisation, was originally sponsored by the South African Council of Churches and the Christian Institute of Southern Africa.

Operating from four offices across South Africa, the BCP clearly expressed concern for the desperate conditions of urban and rural Black communities and implemented programmes in response to their challenges. Along with the head office of the BCP at 86 Beatrice Street in Durban, there were regional branch offices at 15 Leopold Street in King William’s Town (also known as eQonce), Eastern Cape, and at 80 Jorissen Street in Braamfontein, Johannesburg. After the programme’s Executive Director Bennie Khoapa was banned in October 1973 and his movement was restricted to Umlazi, a Durban township, the Natal Regional Office was opened in the same area. Christian networks were critical in providing office space in a context in which more overtly political organisations were banned.18

The site where the Njwaxa Leatherwork Factory was once located in Njwaxa village near Middledrift in the Eastern Cape.

(Source: Steve Biko Foundation)

The BCP was made up of a broad range of projects that included research and publications, health centres, a factory, and a trust fund. All of these projects sought to create the conditions for Black people to be self-reliant, politically conscious, and the drivers of their own development and liberation.

BCP Research and Publications

Black Consciousness activists were determined to transform research by and about Black South Africans and ensure the publication of their work. Ramphele noted the importance of this in Bounds of Possibility, writing that ‘Black people had previously been used mainly as objects of research and that reinforced their self-image as “those acted upon” rather than as active agents of History.’

In 1972, Biko initiated Black Review, an annual journal that sought to address the need for an alternative approach in South Africa by surveying major events in the country. The original intention of publishing Black Review was to openly expose what the Black community had attained or failed to attain: direction taken by Black people in South Africa in matters that affected their situation as Black people as well as to assert their common or varied aspirations. With the assistance of volunteers Tomeka Mafole and Welile Nhlapo, Biko carried out research using newspaper reports, annual reports from organisations working within the Black community, the Government Gazette, and interviews with community workers and leaders across South Africa. The first edition of Black Review was slated to come out in 1972 but came out in the early months of 1973. In this edition, Khoapa was credited as the editor because Biko’s banning order in March 1973 prohibited him from participating in the publications. BCP were also precluded from acknowledging his editorship of Black Review 1972.

This was a common way of working around state repression. After Khoapa himself was banned in October 1973, Mafika Gwala’s name replaced Khoapa’s in that year’s edition of Black Review. After Malusi Mpumlwana, who edited the 1974–1975 edition, was banned in October 1973, Thoko Mpumlwana (née Mbanjwa) was credited for that edition. When Thoko Mbanjwa was banned in 1976, Asha Moodley (née Rambally) appeared on the cover of the 1975–1976 edition underneath a thick black line that covered the text where Mbanjwa’s name had appeared.

Black Consciousness organisations and activists were enthused by Black Review. According to Black Consciousness stalwart Asha Moodley, this publication ‘was used by researchers, libraries, educational institutions, and those people who were interested in history because it strove towards projecting the objective facts about events and trends within the Black community, presented by black [people] themselves.’19

Another important publication was Black Viewpoint, where Black people wrote about current and relevant issues. It was launched in 1972 with issues edited by Biko and Khoapa. In a Black Viewpoint introduction in 1972, Biko wrote:

Our relevance is meant to be in the sense that we communicate to blacks things said by blacks in the various situations in which they find themselves in this country of ours. We have felt and observed in the past, the existence of a great vacuum in our literary and newspaper world. So many things are said often to us, about us and for us but very seldom by us… In terms of this thinking, therefore, Black Viewpoint is meant to protect and further the interests of black people.20

Another publication produced by BCP, Black Perspectives, was published in 1973. Though it was meant to be a series, it was discontinued after only one issue. The first manuscript of Black Perspectives was confiscated by the police when they seized BCP materials. Catering to Black academics and professionals and more scholarly in tone, the volume included in-depth studies generated by Black scholars on issues affecting the Black community. Future issues of Black Perspectives planned to showcase writing on history, culture, theology, education, and literature and to encourage empirical research and publications.

In June 1973 , a directory of voluntary organisations in the Black community entitled Handbook of Black Organisations was produced. Hadfield explained that in the Handbook,

BCP hoped to ‘introduce’ these groups to each other and the public in order to help them understand what ‘each … is involved in doing’ and draw out the common elements of ‘self-help, self-reliance and self-determination.’ Nearly one hundred pages long, it covered organisations ranging from cultural to professional, political, educational, religious, and welfare agencies. … The BCP hoped that, together with the Handbook, it could act as a ‘central registry’ and assist ‘community leaders like clergymen, social workers, teachers, sociologists, businessmen and administrators in the course of their daily work.

Black Community Programmes planned to update the Handbook annually but only published one edition because of financial constraints.

BCP Health Centres

The Zanempilo Community Health Centre was established in January 1975 in Zinyoka, a village in rural Ciskei within the restricted area delineated by Biko’s banning order, ten kilometres outside of King William’s Town (eQonce) in the Eastern Cape. Zanempilo means ‘the one bringing health.’ Its first medical officer was Dr Mamphela Ramphele; as the workload increased, two more doctors, Dr Siyolo Solombela and Dr Sydney Moletsane, joined the team.21

A second health centre named Solempilo (meaning ‘eye of health’) was built near Adams Mission in Durban. However, before it could become operational, it was closed when all Black Consciousness organisations were banned on 19 October 1977, an infamous day still remembered as Black Wednesday. Subsequent to the banning, Zanempilo Health Centre was taken over by the government of Ciskei, a so-called homeland (a system based on the American reservations for Native Americans) led by Chief Minister Lennox Sebe. After the end of apartheid rule in 1994, Zanempilo was taken over by the new government of South Africa and is still functioning to this day.

The Njwaxa Leatherwork Factory

Black people were marginalised economically during apartheid. The BCP attempted to rectify this by opening the Njwaxa Leatherwork Factory in 1974 to give the Black people who worked there a measure of economic independence. The factory was opened in the rural village of the same name situated about 48 kilometres from King William’s Town on the road to Alice (eDikeni). It operated for four years, manufacturing items such as belts, handbags, saddles, cushions, shoes, sandals, fishing-rod holders, purses, and tobacco pouches. Among Black Consciousness supporters involved in this project were Malusi Mpumlwana, his sister Vuyo Mpumlwana, Voti Samela, and Mxolisi Mvovo. This factory too was closed when all Black Consciousness organisations were shut down by the apartheid regime in October 1977.

Zimele Trust Fund

The Zanempilo Community Health Centre in Zinyoka, ten kilometres outside of King William’s Town in the Eastern Cape.

(Source: Steve Biko Foundation)

The BCP started the Zimele Trust Fund to provide support to former political prisoners, supplying them with basic necessities such as clothing, essential furniture, and food, and offering study bursaries for their children. In order to encourage and enable the creation of income-generating self-help projects, the Zimele Trust Fund also made grants available to them (Zimele means ‘stand on your own feet’). Mapetla Mohapi, the administrator of the Zimele Trust Fund, was killed in police custody on 5 August 1976. As was the case with all Black Consciousness organisations, the Trust Fund was also shut down in October 1977.

Conclusion

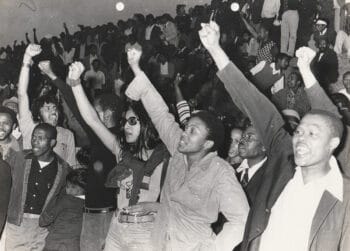

In May 1976 in Pretoria, while still under a banning order, Biko gave testimony about the Black Consciousness Movement at the SASO/Black People’s Convention trial (1975–1976).22 The accused were Saths Cooper, Muntu Myeza, Patrick ‘Terror’ Lekota, Aubrey Mokoape, Nkwenkwe Nkomo, Pandelani Nefolovhodwe, Kaborone Sedibe, Zithulele Cindi, and Strini Moodley. They were on trial for organising the Viva FRELIMO rally, which took place at Curries Fountain Stadium in Durban on 25 September 1974 in support of FRELIMO’s 1974 victory in Mozambique.

In the words of Black Consciousness stalwart Vino Reddy:

The rally was held to stand in solidarity with Frelimo in Mozambique on attaining their hard-fought freedom. … We sang and danced until we were set upon by the police with dogs and batons. I was arrested while trying to assist a man who was being bitten by a dog. I was taken in the back of a police van to the Smith Street Police Station and charged with leading a Riotous Assembly and held in a cell for 48 hours under the General Law Amendment Act. I had no recourse to an attorney or family. On the evening of the 27th September, 1974 the security police arrived and informed me that I was now detained under Section 6 of the Terrorism Act. I was removed to Amanzimtoti Police Station and held in solitary confinement, incommunicado.

As Reddy described it, this demonstration, celebrating a victory by a communist-aligned national liberation movement, was regarded as a serious threat by the apartheid state.

The trial of the organisers of this demonstration marked the beginning of the end of the Black Consciousness Movement as it was known at that time: just over a year after the trial, in September 1977, Biko was killed while in detention. In October of the same year, the Black Consciousness Movement and all of its affiliates were banned by the NP government. Nonetheless, in the years since, the Black Consciousness Movement has continued to inform and inspire resistance movements in South Africa.

When Biko was asked by David Saggot, the senior counsel for the defence, to describe the Black Community Programmes, he responded:

The approach of BCP is three pronged. First we engage in the form of direct community development projects which are in the form of clinics, churches, and so on. And then we engage in what we call home industries–these are economic projects, in rural areas mainly, sometimes in urban areas as well… And the main purpose here is to give employment to people, and offer some kind of technical training in that particular skill… And thirdly we do leadership-training courses.23

The Black Community Programmes succeeded in advancing a legacy of community development for political transformation that continues to inspire activists today. The ideas developed and taken up in this five-year period of ferment (from 1972 till the banning in October 1977) have also sustained influence in contemporary South Africa. In the early 1970s, Freirean ideas about praxis moved from the Black Consciousness milieu to the trade union movement, and then the community-based struggles of the 1980s. They remain present in current forms of popular organisation and struggle. A high price was paid for this period of political creativity. Activists were detained, sentenced to imprisonment, and received individual banning orders, and a number of them were killed. Their role in the history of South Africa should be studied, recorded, and remembered.

Vino Reddy (née Pillay) in dark glasses during the Viva FRELIMO rally, photograph taken outside of the Curries Fountain Stadium in Durban, 25 September 1974.

(Source: Vino Reddy)

The banning of the Black Consciousness Movement and the organisations falling under its ambit dealt a crippling blow to resistance against apartheid. The clampdown was comprehensive, affecting all levels of society, from community organisations to black journalists’ associations.

Even though the repression was draconian, resistance continued in varied ways. As veteran journalist and anti-apartheid activist Joe Thloloe said, ‘the oppressed had a way of responding to the oppressor.’24

Endnotes

- ↩ Frantz Fanon, The Wretched of the Earth (London: Penguin Books, 2001), 166.

- ↩ Derek Hook, ‘New Books | Robert Sobukwe’s letters from prison’, New Frame, 21 March 2019, https://www.newframe.com/new-books-robert-sobukwes-letters-prison/.

- ↩ Hook, ‘Sobukwe’s letters.’

- ↩ Hook, ‘Sobukwe’s letters.’

- ↩ Steve Biko and Aelred Stubbs, ed., I Write What I Like: Steve Biko a Selection of His Writings (Johannesburg: Picador Africa, 2017), 22.

- ↩ Biko and Stubbs, eds., I Write What I Like, 101.

- ↩ Biko and Stubbs, eds., I Write What I Like, 101.

- ↩ Biko and Stubbs, eds., I Write What I Like, 33.

- ↩ Biko and Stubbs, eds., I Write What I Like, 52.

- ↩ Biko and Stubbs, eds., I Write What I Like, 16–17.

- ↩ Biko and Stubbs eds., I Write What I Like, 158.

- ↩ Black Community Programmes. Black Community Programmes: 1973 Report (Durban: Black Community Programmes, 1973), 3.

- ↩ Leslie Anne Hadfield, ‘Conscientization in South Africa: Paulo Freire and Black Consciousness Community Development in the 1970s,’ International Journal of African Historical Studies 50, no. 1 (2017): 79–80.

- ↩ Barney Pityana, Mamphela Ramphele et al., eds., Bounds of Possibility: The Legacy of Steve Biko & Black Consciousness (Cape Town: David Philip Publishers, 1991), 157.

- ↩ Pityana, Ramphele et al., eds., Bounds of Possibility, 154.

- ↩ Pityana, Ramphele et al., eds., Bounds of Possibility, 155.

- ↩ Xolela Mangcu, Biko: A Biography (Cape Town: Tafelberg, 2017), 155–156.

- ↩ According to Ian Macqueen in Re-Imagining South Africa: Black Consciousness, Radical Christianity and the New Left (2011), 86 Beatrice Street was set up as follows: ‘ American Board Mission minister and Congregational Church of Southern Africa treasurer Howard Trumbull rented an empty upstairs room in the church offices at Beatrice Street to SASO, which he was able to do as the treasurer without permission from the church authorities. … His son, David Trumbull, attended Natal University for two years, met and spoke with Biko at the campus in 1969, and was involved in student politics there. Dave recalls being asked by Biko if he was aware of any space that could be used by SASO…’ The regional office at 15 Leopold Street in King William’s Town was, according to Ramphele in Bounds of Possibility (1991), ‘set up in response to Steve Biko’s banning and restriction to that area in 1973…’ According to Lindy Wilson in Steve Biko: A Life (2012), ‘ Very soon after his arrival, Biko located the Anglican priest, David Russell, who had broken the news of his banning to his mother [Alice Biko a.k.a. MamCethe]. Russell lived in a small house on the grounds of the church of St Chad’s in the heart of King William’s Town’s white residential area: no. 15a Leopold Street. The church had not been used for a year… When Russell approached the priest in charge, James Gawe, they agreed it should be used as an office for SASO and BCP… [and] a new committed community began to form.’

- ↩ Asha Rambally, ed., Black Review 1975-1976 (Lovedale: Black Community Programmes, 1977), vii.

- ↩ Steve Biko, ed., ‘Introduction,’ Black Viewpoint (Durban: Spro-cas/BCP, 1972).

- ↩ Ramphele remembers in Bounds of Possibility (1991) that, ‘Zanempilo quickly became a meeting place for all activists in the area. It also served as a guest house for visitors from far and wide who came to see the project or to consult with Steve Biko (who was under banning orders) over a range of issues.’

- ↩ This trial is known as the ‘Trial of Ideas’ or the ‘SASO/BPC Nine Trial.’

- ↩ Millard W. Arnold, ed., The Testimony of Steve Biko (Johannesburg: Picador Africa, 2017), 131–132.

- ↩ Mwelela Cele, ‘What Black Wednesday means for media today,’ New Frame, 19 October 2018, www.newframe.com

Bibliography

Arnold, Millard W., ed. The Testimony of Steve Biko. Johannesburg: Picador Africa, 2017.

Black Community Programmes. Black Community Programmes: 1973. Durban: Black Community Programmes, 1973.

Biko, Steve, and Aelred Stubbs, ed. I Write What I Like: Steve Biko a Selection of His Writings. Johannesburg: Picador Africa, 2017.

Biko, Steve. Interview by Gail Gerhart. 24 October 1972. Transcript, Historical Papers Cullen Library, University of Witwatersrand, Johannesburg.

Biko, Steve, ed. Black Viewpoint. Durban: Spro-cas/BCP, 1972.

Cele, Mwelela. ‘What Black Wednesday means for media today.’ New Frame, 19 October 2018. www.newframe.com

Fanon, Frantz. The Wretched of the Earth. London: Penguin Books, 2001.

Hadfield, Leslie Anne. Liberation and Development: Black Consciousness Community Programs in South Africa. East Lansing: Michigan State University Press, 2016.

Hadfield, Leslie Anne. ‘Conscientization in South Africa: Paulo Freire and Black Consciousness Community Development in the 1970s.’ International Journal of African Historical Studies 50, no. 1 (2017): 79-98.

Hadfield, Leslie Anne. Multiple interviews. 2008–2010. Transcripts, Oral History Collection, Steve Biko Foundation and Steve Biko Centre Archives, Ginsberg, eQonce.

Hook, Derek. ‘New Books | Robert Sobukwe’s letters from prison.’ New Frame, 21 March 2019. www.newframe.com

Langa, Mandla and Ari Sitas, ed. Mafika Pascal Gwala Collected Poems. Cape Town: South African History Online, 2016.

Macqueen, Ian M. Black Consciousness and Progressive Movements Under Apartheid. Pietermaritzburg: University of KwaZulu-Natal Press, 2018.

Macqueen, Ian M. ‘Re-imagining South Africa: Black consciousness, radical christianity and the New Left, 1967-1977.’ PhD diss., University of Sussex, 2011.

Magaziner, Daniel R. The Law and the Prophets: Black Consciousness in South Africa, 1968–1977. Johannesburg: Jacana Media, 2010.

Mangcu, Xolela. Biko: A Biography. Cape Town: Tafelberg, 2017.

Pityana, Barney, Mamphela Ramphele et al., eds. Bounds of Possibility: The Legacy of Steve Biko & Black Consciousness. Cape Town: David Philip Publishers, 1991.

Rambally, Asha, ed. Black Review 1975-1976. Alice: Lovedale Press, 1976.

Wilson, Lindy. Biko: A Life. Ohio: Ohio University Press, 2012.

Woods, Donald. Biko. Essex: Paddington Press, 1978.