A niche clinic

At 8 a.m every Wednesday, Dr. Pan Bolin of the Department of Transformative Surgery at Peking University Third Hospital opens the doors to his Gender Dysphoria Clinic. He gets to his desk early, atop which a hormone treatment flowchart and a variety of transgender literature greet him.

Apart from just counseling patients, he also needs to educate the parents who accompany them about transgender issues. It means his morning clinic schedule is often delayed until noon or even later.

On a July afternoon in 2020, Liu Meng and her mother waited at the entrance of the clinic. She recalls that most patients were with their parents, nearly all with gloomy faces, gripping their cell phones in silence.

Liu, however, did see one couple cheerfully accompanying their child into the clinic. She found it an incredible sight, and recalls thinking to herself,

What a lucky kid.

A trans woman, Liu is currently a freshman at a university in Beijing. Last summer, Liu, then an 18-year-old, visited this clinic for the first time. At that time, Dr. Pan spoke with Liu’s mother about what it meant to be transgender, the most important takeaway being that it is no longer considered a medical condition.

The most direct manifestation of Dr. Pan’s efforts to depathologize transgender people is to call them “visitors”–it avoids offending or unnecessarily discriminating against the community.

In May 2019, the World Health Organization (WHO) removed gender dysphoria, or gender identity disorder, from the International Classification of Diseases. In China, however, being transgender is still classified as a mental illness, and transgender people require a “certificate of mental illness for gender dysphoria” before using hormones or getting sex reassignment surgery.

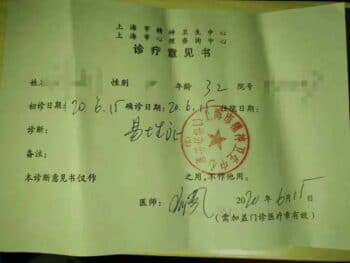

Liu received her mandatory gender dysphoria certificate from a psychiatric hospital the day before she saw Dr. Pan.

Liu’s gender dysphoria diagnosis certificate. These certificates are mandatory in China for anyone who wants to undergo gender reassignment surgery. (Photo: Beijing Youth Daily)

While researching Dr. Pan online, Liu had only gathered that he was “mild” and “friendly.” When she first met him, he rarely smiled but his voice was soft, and he spoke slowly. Liu also noticed that her mother listened to Dr. Pan attentively. “He said the same thing, but for me to say this might not be a disease, and for Dr. Pan to say it–it isn’t quite the same,” says Liu.

Dr. Pan told Liu and her mother that treatment would involve three steps, starting with psychological adjunctive therapy–allowing Liu to better understand herself and her body. If this allowed her to accept herself, she wouldn’t need further help. If not, the next step would be hormone therapy under medical supervision. The third step was surgery.

Liu recalls that her mother was calm. She says,

She was probably still trying to accept and understand all this new information.

At the time, Liu still had close-cropped hair but felt she didn’t need to explain her attire, behavior, or thoughts in this small clinic. She knew Dr. Pan understood it all, and this gave her a sense of relief that spread from her heart through her whole body, “like seeing my savior and grabbing a lifeline.”

In 2016, Dr. Pan opened China’s first center for the transgender community, integrating the resources of various departments. In 2017, he opened the Comprehensive Gender Dysphoria Clinic.

For Dr. Pan, it was all part accident, part destiny.

In 2010, as a plastic surgeon, Dr. Pan visited the Showa University Hospital in Tokyo, Japan. While there, he read a book that compiled reports and recommendations on the diagnosis and medical support for gender dysphoria.

Its contents always brings back memories of the transgender people he’s met, starting two years when he worked in surgery. Then, a transgender person underwent sex reassignment surgery at the hospital and he was responsible for her medication.

At the time, his view of the transgender community was the same as many others–incomprehensible, yet curious. He admits feeling a little apprehensive and uncomfortable around her.

But after meeting her a few times, Dr. Pan found she was frank, gentle, and stoically tolerated the pain he caused by his then amateurish technique.

“It doesn’t matter, keep going, come on,” she would say to him. When the patient was discharged from hospital, she asked him where she could get hormone therapy. He was stumped by the question. He asked some other physicians, and they too were flummoxed.

That’s when Dr. Pan had a revelation. He translated the book he’d read while in Japan into Chinese and posted it online. At the time, it was difficult to find medical information on transgender medicine on websites in China.

Soon after, some members of the transgender community began leaving Dr. Pan messages asking him about hormone use and surgery. When he didn’t know the answer, he always went back to the book.

In the initial months after forming a team and starting the clinic for transgender people, Dr. Pan often still had to rely on international guidelines. He underscores that he will persist in this “ignored” field, and that transgender medical care is a worthwhile endeavor.

From self-help to support

Getting professional medical support is an uphill battle for the transgender community in China.

After the college entrance exam or gaokao in June 2020, Liu Meng thought hard about coming out as transgender to her parents–that she wasn’t the son her parents saw her as.

For her father, that conversation came out of nowhere. Liu called him into her bedroom, sat him down, and confessed her gender identity to him.

His reaction was mixed–anger, with bewilderment. Liu recalls sensing her father was doing his best to suppress his true feelings. “He thought I was being influenced by others,” she says.

They were in her bedroom for just a few minutes, which at the time felt extraordinarily long. Liu had anticipated many possibilities, including correctional treatment or “turning back” into the “normal” person her parents always knew.

During her conversation, Liu bluntly stated that she wanted to see a doctor and get legitimate medical help–a decision her parents supported.

To look more feminine, Liu used hormone medication on her own. But she says she was cautious since she was medicating without professional guidance.

Like Liu, Li Qing used hormones on herself too. Now 24, Li was introduced to the concept of being transgender when she was 18 and in college. At the time, she recalls it “felt like the concept might have applied to me.”

Li spent four years making cosmetic changes to explore how it felt. She secretly took hormones for more than three months before getting medical support from Dr. Pan. She used methods she found online from other people’s experiences–but that didn’t work for everyone. At the end of February this year, she visited Dr. Pan’s Gender Dysphoria Clinic.

Cheng Yu, a 33-year-old trans man, says many in the transgender community have access to hormones only from unknown sources online, which sometimes sell animal hormones. “They blend those ingredients used on animals; there’s no manufacturer, no brand, and then say it’s the hormone–take it or leave it. It’s particularly expensive,” says Cheng.

Undoubtedly, this causes physical harm, but the risk is nothing compared to the pain caused by a biological gender that one cannot identify with.

Pan (third from the right) poses for a group photo during a forum on healthcare for transgender people in China, November 2021. (Photo: Beijing Youth Daily)

According to Dr. Pan, close to 80% of the transgender community require hormone treatment. And according to the 2017 Survey Report on the Survival of the Transgender Community in China, published by the Beijing LGBT Center and the Department of Sociology at Beijing University, 33% of transgender people who need hormone treatment obtain drugs through informal means.

Before traveling to Beijing, Cheng went to a local hospital in the southwestern Guizhou province for hormone medication, but they didn’t understand what it meant to be transgender. He says,

They would ask, how come you are female on your ID card? Why do you need a prescription for androgens, and why do you have facial hair?

The experience kept Cheng away from seeking medical treatment.

He eventually stepped into Dr. Pan’s office in 2017 for the first time while in Beijing for work. By then, the side effects of taking androgens had raised Cheng’s blood pressure and blood sugar. He needed to be hospitalized for further tests, and required observation for other endocrine diseases.

At the time, Cheng had already undergone breast reduction surgery, but not sex reassignment. And though assigned female at birth, he appeared masculine. The contrast meant assigning the ward he would stay in became complicated.

“It would have been quite embarrassing to stay in a room with a patient according to the gender on my ID card,” he says.

But if I were to stay in a room with someone of the gender I identify as, that person might not accept it either.

That night Dr. Liu Ye, a doctor on Pan Bolin’s team, asked Cheng,

Do you want to stay in the male or female ward?

To this day, Cheng feels moved when he recalls that question. “Dr. Liu consulted me first,” he says. He eventually chose to be admitted to the female ward, in accordance with the gender on his ID card.

Dr. Liu spoke with the other patients in the ward beforehand–they kindly accepted him and even exchanged pleasantries.

Crossing the barrier

For physicians, clinics like Dr. Pan’s are not without obstacles.

Dr. Pan says there aren’t enough doctors willing to engage with the transgender community, which is still on the fringes of society in China.

There are still some doctors who look down on transgender people and even the doctors engaged in helping the community. According to Dr. Pan, some doctors have questioned his motives, asking if he does it for the publicity it draws. The number of doctors in this field “can be counted on his fingers,” he says.

Another point of conflict is between transgender individuals and their parents. Dr. Pan says the lack of understanding or effective communication between them often affects the outcome of medical consultations, and subsequent planning.

Sometimes, such conflicts occur at the clinic itself. Some transgender people are reluctant to open up in front of their parents, and parents end up relaying the information in their stead, often leading to misunderstandings.

It’s why Dr. Pan’s clinic has accompanying psychological support services for transgender people and their parents. Dr. Pan’s assistant, Han Meng, who has a PhD in applied psychology, says many transgender people come to the clinic with their parents.

But parents aren’t there for professional help, and often ask the doctor to “cure” their child. Some parents believe their children have read “deceptive” information on the internet about being transgender and demand that doctors “change” their child back.

According to Han, many patients at the clinic are severely depressed. He says many sit there “not saying a word, the parents doing all the talking. They look depleted.”

When faced with parents who have difficulty “giving in,” Han asks them to weigh their choices: accept their children’s decision to change gender, take hormones, and undergo surgery; or reject them and force them to live in pain, leading to anxiety, depression, and even self-harm or suicide.

When parents slowly accept their children, transgender people themselves feel much better. Han says, “Many parents come here and cry, they just don’t understand their child’s ideas and feel pained and helpless. We provide a sort of outlet for their emotions.” There are also parents who break down while asking Dr. Pan,

Doctor, so can you help my child change back?

Some parents may seek correction therapy for their children. In a public speech, Dr. Pan had said:

Unfortunately, history and lessons learned from previous cases have proven that correction therapy is ineffective and even counterproductive. The reason is simple: sexual minority status is an inherent characteristic, not a mental illness, not an acquired habit, and not something that can be easily changed by reinforcing certain behaviors.

He continued,

Some transgender people have been forced by their parents to go to correction facilities and subjected to electrical shocks, injections, humiliation, restrictions of personal freedom, and other cruel methods. Some treatments have even led to serious consequences, like running away, aggravated depression, and even suicide.

In Han’s opinion, that some parents went from initially resisting and not allowing doctors to help their children, to not agreeing with or opposing their children’s choices, is a transformation in itself.

“Although some parents didn’t immediately support their child, because of our clinic, they went from confrontation to letting the child take charge of their own life. The parents gave their child some room to live within their own means,” says Han.

At first, Li Qing’s mother refused to accept she was transgender, and did not trust Dr. Pan.

But after reading a large amount of literature from him, her attitude slowly changed. She neither supported nor opposed her daughter, but that was enough for Li Qing.

Given this lack of trust or misunderstanding, parents often complain to the hospital about Dr. Pan.

Some alleged Dr. Pan colluded with psychiatrists to prescribe drugs and profit from their children. Once, a parent once reprimanded him that his child became transgender because Dr. Pan’s clinic gave the child poor guidance and “turned the child bad.”

Dr. Pan sympathizes with such parents. “It’s all a natural reaction when there’s no understanding of the transgender community, and we can only do our best to educate the public about the science,” he says.

There are often difficult situations at the clinic. On one occasion, a mother rushed into the clinic and anxiously told Dr. Pan that her child had registered for hormone therapy. She begged him to tell her child that taking hormones was very harmful, and to talk him down.

As he was about to give her a scientific explanation, she burst into tears, saying her family had been torn apart by her child’s decision, and that she didn’t want to live if her child was transgender.

Dr. Pan said he would try to persuade the child, depending on the situation. The mother bowed deeply, and left quickly so her child wouldn’t know of her prior visit to the clinic.

When Dr. Pan saw her child, he found they were very determined to use hormones–but he was afraid the treatment would aggravate the family’s conflict, and wanted to find a way to calm tempers first.

He noticed two indicators in the lab tests were slightly abnormal. Though this didn’t affect the use of hormones, he told the patient:

This may pose some risks to the medication, can you see an internist to clarify these conditions before continuing?

Disappointed, the person silently turned away and left the consultation room. A few days later, Dr. Pan got a message from the same patient on an online medical platform. It read:

Thank you, Dr. Pan, for taking care of me last time. I have bought a ticket to Xiamen and plan to commit suicide. Thank you, doctor.

Dr. Pan panicked and immediately contacted all parties involved to search for the person–and fortunately found them in time. “Otherwise, this was enough to leave me guilt-ridden for the rest of my life,” he says.

Pan gives a speech on Yixi, regarded by some as the Chinese equivalent to TED Talks, July 24, 2021. (Photo: Beijing Youth Daily)

Since that incident, he’s decided to firmly abide by the principle that when faced with pleas from parents, he’ll help them understand but will not compromise their children’s rights.

The importance of empathy

Every week, 10 to 20 transgender people visit Dr. Pan’s clinic. Counting the comprehensive consultations online, in five years, his team has provided medical help to more than 2,000 transgender people, ranging from teens to people in their 60s.

And each one has their own story.

One trans woman in her 60s visited the clinic for a consultation on sex reassignment surgery. In her medical records, Dr. Pan discovered she had gone to hospital more than 20 years earlier. She told Dr. Pan that she couldn’t sleep the night before the surgery at the time, thinking about the fact that she was married with children, and worked at a public institution.

Since she hadn’t told them, she asked herself, over and over, “What about my family? What about my children? What about my parents?” The next day, she decided against the surgery.

Years later, after her children had grown up and her parents had passed away, she finally confessed to her wife her desire for surgery. She walked into the hospital for the second time. The first step of her surgery was successful, and she’s now awaiting the second procedure.

Around four years ago, another transgender person came to the clinic for hormone therapy. But his religious beliefs created additional pressure, and he often showed signs of helplessness. Doctors often saw him aloof in a corner, praying silently.

Dr. Pan spent hours listening to him, and took the initiative to talk to him about his life. Sometimes he talked for an hour, and Dr. Pan listened quietly, often delaying the end of his shift.

Every holiday since, Dr. Pan has received a card from him. Sometimes the cards describe his daily life, his thoughts, the effects of using hormones, or just a few simple wishes.

“I give them as much help as I can within the context of protocol,” says Dr. Pan. When a transgender person comes in for the first time, he speaks about their daily routines, and gives advice on communicating with people around them, like asking for help or getting along with parents.

Empathy is especially important in this small clinic. “If parents are sad, you need to empathize with them from the bottom of your heart and communicate with them that it’s serious and important to their children,” says Dr. Pan.

For him, the ultimate goal of all medical treatment is for transgender people to be able to accept themselves and their bodies and return to their daily lives successfully.

Liu Meng’s plan constantly changes. Earlier, she was eager to complete sex reassignment surgery, but with hormone therapy, she’s become more cautious.

“If you are too busy to get the surgery without understanding what you want, the final result won’t be very good, and it might even backfire,” she says. She hopes to give herself a little more time, under the condition that she keeps her health intact.

Now, Liu Meng needs a follow-up every three months and her test results checked by Dr. Pan before prescribing a new course.

In addition to treatment assurances, she receives the same psychological support at the clinic.

It’s a place where I don’t have to face uncomfortable stares from others who don’t understand.

While Li Qing was waiting in line, she saw a middle-aged man at the clinic. He said his child was like “them” and he’d accompanied his child to see Dr. Pan. He was at the clinic just to take a look because only here could he see the kind of state his child’s “kind” were in.

When his child first revealed his gender dysphoria, the father was completely overwhelmed, saying he “never thought his child would be like this.” But as he read more information about being transgender, and after talking with Dr. Pan, he gradually began to understand.

But he was still worried about his child’s future. “The younger generation is more tolerant about being transgender, but it’s hard to say further up the line. Whether the child will face discrimination in school and employment in the future is uncertain,” says the father.

Dr. Pan is also well aware that his own capacity is limited and that supporting the transgender community with only medical efforts is not enough. “It’s impossible to get everyone in society to understand the transgender community but at least we’re trying,” he says.

“We will establish an association, write industry standards and treatment guidelines, and organize more lectures and training in the hopes that more doctors will pay attention and join the field. Hopefully, there will be top-down support for transgender people to enjoy their legitimate medical rights.”

Because her work is out of town, it’s difficult for Li Qing to go back to Beijing for future visits. Dr. Pan gave her a copy of the Hormone Treatment Process he’s developed, which details the precautions and procedures for remote treatment. On the back of the document, he’s also written future tests and medications for her.

On July 7, before she left, the clinic was full of people, so Li didn’t get a chance to say goodbye to Dr. Pan. She’s been to his clinic just three times and can only vaguely remember how it looks.

After going back to work, Li will need to regularly check her body’s related indicators to adjust the dosages of medication. With the prescription written by Pan Bolin, she can buy medication–legitimately–at the pharmacy.

However, Li is still worried. She’s afraid other doctors don’t know as much as she does. And she trusts only Dr. Pan.

(Except for Pan Bolin, Liu Ye and Han Meng, the names of the interviewees are pseudonyms, and the use of pronouns respects the wishes of interviewees.)

Additional reporting: Lin Yiquan & Luo Pengfei.

A version of this article originally appeared in Beijing Youth Daily. It has been translated and edited for brevity and clarity, and published with permission.

Translator: Matt Turner; editors: Lu Hua and Apurva.