When Mohamedou Ould Slahi Zoomed into my graduate class from Mauritania in March to discuss his new novel, The Actual True Story of Ahmed and Zarga, he shared a bit about the role writing fiction played during his detention at Guantanamo Bay from 2002 to 2016.

Writing fiction helped him “create a world that doesn’t exist” and “then I picture myself in a world that is so good, so much better than prison.” With this novel, Slahi offers readers a glimpse of the world he created to escape Guantanamo Bay Detention Camp.

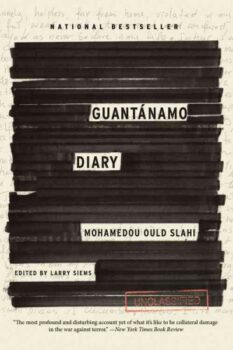

Fiction tells different truths from nonfiction. Released in 2015, Slahi’s nonfiction work Guantanamo Diary chronicles the brutal reality of his experience of extradition and detention by the U.S. government. The truth shared in Guantanamo Diary sheds light on the secret programs that enabled the torture and prolonged imprisonment he suffered.

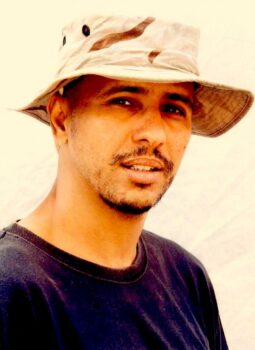

International Committee of the Red Cross took this undated photo at the Guantanamo Bay detention camp in Cuba. They gave it to Salahi’s brother, who passed it on to Salahi’s lawyer. (ICRC, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons)

The Actual True Story of Ahmed and Zarga tells the story of a local Mauritanian camel herder to explore a different sort of truth, the truth about our shared common humanity. If Slahi’s nonfiction condemns the methods of the war on terror, his fiction rebukes the Orientalist images of the Muslim world that provided a rationale for those methods.

The Actual True Story of Ahmed and Zarga was originally drafted while Slahi was a detainee at Guantanamo Bay. After 14 years of captivity without charges, Slahi was released in October 2016, but the original manuscript of Ahmed and Zarga has never been released. Upon his return to Mauritania, Slahi set about rewriting the story from memory and it was published by Ohio University Press in early 2021.

Ahmed and Zarga follows the journey of Ahmed, a devout Bedouin from the fictional Idamoor tribe, as he searches for his beloved camel, Zarga. Set at a moment when traditional Mauritanian life is under threat from a French colonial administration, the novel serves as an allegorical examination of maintaining faith and loyalty to one’s beliefs in a changing and often threatening world. At times, readers will find the unmistakable imprint of Slahi’s own circumstances as he, like Ahmed, tries to maintain his humanity in a harsh and dangerous environment.

Drawing on the rich storytelling tradition in Bedouin culture, Slahi uses an unnamed narrator to encourage readers to sit by the campfire and listen to “the only true version of the story, the real and complete thing.” In addressing readers directly and building in a self-aggrandizing narrator, Slahi inflects the early part of the novel with a lightheartedness that cuts across cultural differences and invites readers to connect with his characters. From the outset, cultural difference is never presented as a problem as the reader is treated like a welcomed guest in the pages of the novel.

As Ahmed travels into the desert in his quest to bring Zarga home, he faces a range of hardships that take him farther and farther from his village and into increasingly dire circumstances. These moments reveal the fragility of life and a reliance on others, the natural world, and limited resources for survival. These events do not engender pity or sympathy, emotions that reinforce distance and difference between a reader and text, but instead offer a reminder of our underlying vulnerability.

As Ahmed travels into the desert in his quest to bring Zarga home, he faces a range of hardships that take him farther and farther from his village and into increasingly dire circumstances. These moments reveal the fragility of life and a reliance on others, the natural world, and limited resources for survival. These events do not engender pity or sympathy, emotions that reinforce distance and difference between a reader and text, but instead offer a reminder of our underlying vulnerability.

At times readers will find the link between Slahi and Ahmed unavoidable. This connection is particularly evident when Ahmed is captured and held prisoner near the conclusion of his quest. These scenes are imagined with painful details and convey a disorienting feeling that highlights the incomprehensibility of the situation.

After Ahmed is imprisoned he is left questioning, “Why did they drug him? Why did they shackle him like a crazy bull? What else did they do to him while he was unconscious?” As the tension escalates, Ahmed reaches a moment in which he thinks he will die. He reflects that “all traces of hate and resentment toward others were erased from his heart. Even toward those who were about to butcher him he had no hate.” It is difficult to fathom how a person who endured torture and 14 years of detention without ever being charged is still capable of expressing an indomitable human spirit. The grace that permeates the novel reflects a deep humanness that is central to Slahi’s understanding of suffering, war and human relations.

The journey framework keeps readers engaged and following a linear plotline, but there are moments in which the purpose of the journey becomes obscured.

The journey framework keeps readers engaged and following a linear plotline, but there are moments in which the purpose of the journey becomes obscured.

Towards the end of the novel some of Ahmed’s ordeals seem to be spaces in which Slahi is processing trauma, which results in a significant shift in tone and subject matter from the outset of the novel. This shift does not diminish the core themes of the novel, but reveals how our humanity wrapped up in both good and bad experiences.

Towards the end of Slahi’s visit with my class, he expressed the sentiment that “we are much more like each other than we are different from each other.” The class grew silent in that moment and was in awe of Slahi’s unshakable commitment to a shared humanity in the wake of all that he has endured. The Actual True Story of Ahmed and Zarga stands as a testament to that belief and as an imam reminds Ahmed, “we are all brothers and sisters.”

While Slahi created the world of Ahmed and Zarga to escape his detention, his willingness to share that world with readers is an act of generosity and gift to us all.

Alexander (Sandy) Hartwiger is an associate professor of English at Framingham State University where he teaches contemporary postcolonial and African literature.

This article is from Africa is a Country and is republished under a creative commons license.