This week and through November 12, the United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP26) takes place in Glasgow, Scotland. COP26 brings together heads of state and other prominent figures to talk about climate change. However, the conference won’t address the central environmental problem: capitalism. In this interview we talk to Max Ajl, author of A People’s Green New Deal (Pluto Press, 2021), which examines the capitalist roots of the environmental crisis, and addresses its impact on countries of the Global South such as Venezuela.

It’s important to bring up the Global South’s perspective on climate change in the context of COP26. In A People’s Green New Deal you argue that so called “green economies” (and in general the proposals that we know as the Green New Deal-GND) often replicate the existing logic of domination, particularly when it comes to the Global South. Briefly, can you explain your hypothesis?

Mao put this simply: “Everything reactionary is the same; if you do not hit it, it will not fall.” We can add: you have to take aim to hit.

The great majority of progressive proposals take aim neither at capitalism nor imperialism. In fact, they are often blind to them. If we want to change the world-system, we need to have a sense of what it is. In the most general sense, drawing on Samir Amin, we can say that it is a system of polarized accumulation, producing great mountains of wealth, on the one hand, and far larger seas of poverty, on the other. That is a feature and not a bug of the system: the wealth accumulated at the core of the system is stolen from the periphery. To change that type of world-system, you need first of all to strike at the current mechanisms of value transfer from periphery to core. Those include uneven exchange of values–or the core receiving goods embodying more labor than those embodied in its exports–and the core receiving goods which concentrate more of the world’s resources than those it exports. Another element is: ongoing primitive accumulation, including the collapse of peripheral sovereignty, as in Yemen and elsewhere, which is part of safeguarding the petrodollar.

The 2010 Cochabamba People’s Agreement went further. It recalled the (unrealized) Bandung-era effort to achieve political and economic decolonization and liberation. But the Cochabamba Agreement added something new: we need to speak of ecological decolonization. In other words, the global ecology’s sinks for waste from CO2 emissions were not just used. They were enclosed by the wealthy states. Because that space cannot be restored in the short term, southern states/peoples are owed some kind of replacement: climate debt, to the tune of six percent of northern GNP per year.

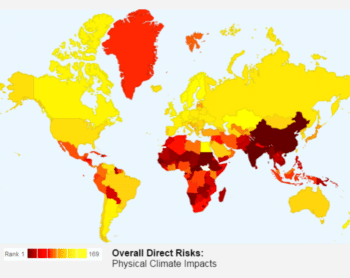

This map shows that the countries of the Global South are the most affected by climate change. (Photo: University of Richmond)

These are structural features of the world system. Unless you identify them, target them, and strike at them, they won’t fall. They will continue. So, logically, the prevailing proposals for a GND, or for a “green economy,” will simply reproduce the polarized system if they do not take into account these logics, diagnoses, structures, and demands. They will tend to look away from the historical sources of wealth and not support reparations. The point is that we cannot subsist on a politics of GNDs based on slogans such as “just transition,” “sustainable development,” or even “a Green New Deal,” socialist or not, unless they specifically mention these demands and the mechanisms of uneven development.

With that in mind, what kind of reorganization on a global scale is needed so that the people of the Global South don’t end up paying the consequences of the climate crisis?

There are five fundamental elements that are central to reconfiguring North-South relations (the specific internal texture of changes in the Global South’s production and its ecological self-defense strategies are different questions, clearly involving, as the Bolivian leadership has said, food sovereignty and sovereign industrialization among other measures).

One element is the demilitarization of the core states. In effect, southern social movements advanced this demand in the Cochabamba process when they pointed out that the U.S. spends as much on its military as is demanded from the U.S. in climate debt payments. They called for “a new model of civilization in the world without… war-mongering.” Demilitarization is also necessary to achieve a “just transition,” meaning, in concrete terms, stabilization if not improvement in life outcomes for people in the imperial core. Militarization amounts to a horrific use of social surplus and industrial capacity, geared at preserving world accumulation and guaranteeing imperialist value flows. It needs to go.

Second, there needs to be a real respect for sovereignty, and a political struggle to ensure that respect. People in the North need to actively resist their governments’ attempts to economically asphyxiate the South and to impose unilateral coercive sanctions. That means the abolition of the so-called “terror lists,” which are primarily used to criminalize groups in the Arab-Iranian region carrying out any defense of national sovereignty or defense of anti-colonial projects.

The basics of international law need to be respected, including honoring the territorial sovereignty of states like Venezuela and Syria. The latter is occupied by U.S. troops, without any protest from the western left. The former suffers from paramilitary infiltration from Colombia, a U.S. client state–again without much objection from the western left. Needless to say, removing external destabilization does not mean that these countries will suddenly produce autonomist socialist societies. Rather, the removal of external aggression creates a better atmosphere for internal social struggle aimed at more democratic freedoms, internal social(ist) redistribution, and ecological justice.

Third, there needs to be payment of climate debt. Northern environmental movements have purposefully suppressed this demand, inasmuch as they took distance from the Evo Morales and Hugo Chávez governments, all the while hypocritically expressing concern about extractivism (which is an input into the commodities and industrial processes that are key to northern accumulation).

The Cochabamba People’s Agreement and the Bolivian government specifically demanded six percent of northern GNP, around $1.2 trillion from the U.S., and around $3.2 trillion from the OECD on the whole. This includes an adaptation debt, to help “Poor countries and people who live daily with rising costs, damages and lost opportunities for development,” and an emissions debt, since “developed countries’ historical and current excessive emissions are limiting atmospheric space available to developing countries.”

Fourth, there should be a vast and immediate reduction in fossil-energy use and emissions in the Global North, as a consequence of their current and worsening overuse of atmospheric sinks for CO2.

Fifth, there should be settler-decolonization, including support for the national liberation struggles of peoples still fighting against settler-colonial domination in places like Palestine and current-day Canada and the U.S.

Some people argue for an anti-extractivist solution to the crisis. On paper, that might appear to be a great solution. However, people of course actually live in places like Venezuela, Bolivia, and Nigeria, and the conditions of dependency are such that freezing production would be suicidal for them. What policies should be pursued in the extractivist economies of the periphery?

One should acknowledge that anti-extractivist campaigns often reflect real and desperate social issues that people face. For example, people in Bolivia and in Venezuela must deal with horrible ecological harms of resource extraction in their countries. Nevertheless, these anti-extractivist campaigns in the North are often no more than weapons against Third World development.

There is no possible industrialization in any part of the world without resource extraction, especially of minerals. Are people demanding that we live in grass-covered knolls like hobbits? That extraction will produce political, social, and ecological costs, where it occurs is undeniable. The question is how to balance those costs with the majority’s need to escape poverty. There is obviously no simple answer. One answer is to go back to the demands for changes in the terms of trade, (“international action in favor of fair and stable prices for [Third World] exports,” in Ismail-Sabri Abdallah’s phrase).

My point here is both rhetorical and real: all things being equal, if countries could produce half as much lithium or anything else and receive the same proceeds, then resolving difficult developmental dilemmas would be easier. Instead, extractivist theory leads to the “displacement of the debate over politics and policy from North to South,” in the words of Sam Moyo, Paris Yeros, and Praveen Jha. It sidesteps any question of northerners’ responsibility for political transformation (a cynic would say that is why this discourse is so popular!). So one issue is serious international activism around the terms of trade, with the understanding that changes benefitting the Third World, which are entirely possible, could immediately enhance developmental possibilities.

In the words of the Tunisian Observatory for Food Sovereignty and the Environment, “Faced with this conflagration, the obligation to act falls upon all, even if responsibility does not.” Countries cannot simply wait. Venezuela, for example, needs to return to its policies of two decades ago and aggressively support peasant activists’ efforts for agrarian reform. Venezuela is a tremendously rich country in terms of agricultural potential and that potential needs to be realized. The country must be able to feed itself, and furthermore needs to retain more value locally through sovereign industrialization, including a sovereign renewable energy system that could jump-start such a process.

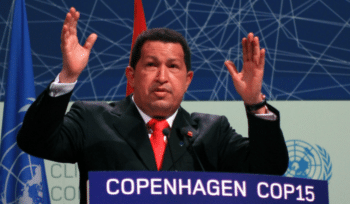

Chávez at COP15 in Copenhagen, Denmark, when he said “Let’s not change the climate, let’s change the system!” (Archive)

It would be good to have better terms of trade with the West and China, but it would be better to retain value through in situ industrialization. I have little to say about the technicalities of protecting Venezuelan farmers from cheaper imported food and an overvalued currency. However, the current crisis, including the kidnapping of Alex Saab, is proof that the basis of a national economy, where possible, is food sovereignty with its capacity to keep inflation under control.

At the COP15 in Copenhagen, Hugo Chávez said: “Let’s not change the climate, let’s change the system!” More recently, Bolivian Vice President David Choquehuanca made a call for an anti-capitalist and anti-imperialist approach to climate change. Can you talk to us about these calls from the Global South?

The North is calling for reforms and crisis-management, and for an essentially Keynesian green shift in the industrial composition of the world system. At best, it seeks a transition to socialism in some undefined future moment, or points to unreal solutions like space mining. By contrast, Chávez and Choquehuanca stepped onto the world political stage, in 2009 and 2021 respectively, and called for ending capitalism. Choquehuanca clearly denounced “limitless accumulation.” He spoke of the threats of “green capitalism” when brought to bear on technologies in the fields of biology, biotechnology, artificial intelligence, and space colonization. Likewise, Chávez spoke of “global imperial dictatorship,” and placed the responsibility for dealing with climate change primarily on the United States and its allies. They clearly named the global-scale problems their countries and the South confront and demanded a solution for them.

Can we deal with climate change in a way that achieves liberation and justice for all of the oppressed world–including oppressed, alienated, exploited, and colonized people in the core countries–without following these two leaders in identifying capitalism and imperialism as the systems destroying the planet? Is it any wonder that people find it more comfortable to discuss Venezuelan and Bolivian extractivism in the imperial core countries, rather than try to respond to the analysis they put forward and the politics which derive from it?