The Nicaraguan elections are on Nov. 7, 2021. The U.S. government, the media that does its bidding, and even some self-described “leftists,” present a Nicaragua in “turmoil” and “crisis”—and the elections as a farce.

These attacks against the Sandinista government also emanate from academics, intellectuals, and journalists with ties to the members of the now-defunct Sandinista Renovation Movement (MRS), an organization with no political relevance or popular support whose members pretend to be leftist to an international audience but support the Nicaraguan right-wing and do the bidding of the U.S—betraying both Sandinismo and Nicaragua.

The people and organizations spewing these anti-Sandinista reports have taken it upon themselves to speak on behalf of Nicaraguans, whom they claim live in some sort of authoritarian nightmare that only U.S. intervention and the “international community” can fix.

Inside Nicaragua something else is afoot. The country is peaceful, getting ready for year-end activities that begin in November. People are going about their everyday business with interest but not obsession with the elections, as usually occurs in the U.S., where every inane and self-serving photo-op and publicist-generated skirmish is reported ad nauseum.

No doubt there is plenty of news reported about the elections. For example, poll after poll, in various regions of the country, show majority support (about 2/3) for the Sandinista National Liberation Front (FSLN)’s ticket, with Daniel Ortega at the helm; in the North of the country, the support is even higher.

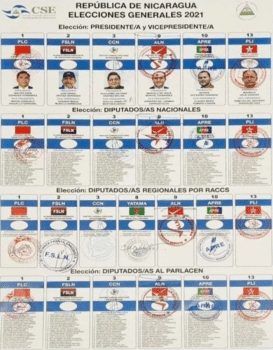

About 180 international electoral “companions” will observe the elections. Some 245,000 Nicaraguans will be involved in working the elections as poll watchers, polling station board members, electoral police, and voting center coordinators. All parties registered their poll representatives by October 14. In conjunction with the Ministry of Health, the Supreme Electoral Council (CSE) issued a range of health measures to prevent the spread of COVID-19, which include the avoidance of massive in-person events while prioritizing virtual platforms.

In-person events must be carried out in open areas with no more than 200 people. No caravans are allowed. With regards to voting, in late July, Nicaraguan citizens had the opportunity to update and check their address to verify their polling station; citizens can also check online. The CSE also notes that one cannot vote with witnesses or with a photocopy of one’s ID—although expired IDs can be used to vote, a measure taken to increase participation of the electorate. On Nov. 1 electoral material was sent to the 153 municipalities of the country. In sum, CSE, the Nicaraguan government, and the citizenry are very well organized and ready for the elections.

In-person events must be carried out in open areas with no more than 200 people. No caravans are allowed. With regards to voting, in late July, Nicaraguan citizens had the opportunity to update and check their address to verify their polling station; citizens can also check online. The CSE also notes that one cannot vote with witnesses or with a photocopy of one’s ID—although expired IDs can be used to vote, a measure taken to increase participation of the electorate. On Nov. 1 electoral material was sent to the 153 municipalities of the country. In sum, CSE, the Nicaraguan government, and the citizenry are very well organized and ready for the elections.

The issues that will determine election outcomes are straightforward. Nicaraguans are concerned, among other things, about their economic well-being. The Nicaraguan economy’s strong and enviable financial performance came to a screeching halt due to the U.S.-backed coup d’état in 2018. As a consequence, thousands of people have left the country in search of work and economic stability—something that continues to be cynically reported in Western media as massive emigration due to government crackdowns, which is demonstrably false.

Since the failed U.S.-backed coup, the Sandinista government has gone into hyperdrive to recover the economic trajectory it was on prior to the U.S.-funded attack. All economic indicators, particularly this year, suggest that Nicaragua is, in fact, recovering at neck-breaking speed, including an expected 6-8% GDP growth in 2021, to the chagrin of their aggressors.

Nevertheless, some families have had more difficulty than others, leading some to consider—and some of them to depart for—the United States.

U.S. Aggression and Subsequent Migration

During the electoral campaign, the Biden team promised a more humane, just, and rule-bound immigration regime in contrast to Trump’s. They communicated to Central Americans that they would be treated more fairly and even welcomed at the U.S. border.

The advertisement campaign worked. People in the U.S. and all over the world—including in Nicaragua—believed what they said. Thousands embarked on their journey to the United States, believing they would be allowed in.

The advertisement campaign worked. People in the U.S. and all over the world—including in Nicaragua—believed what they said. Thousands embarked on their journey to the United States, believing they would be allowed in.

In addition, in the U.S., immigrant workers seem necessary due to increasing layoffs following vaccine mandates among blue-collar workers and U.S. citizen worker resistance to ever devolving labor conditions, including low pay, non-existent benefits, COVID fears, and increasing demand.

Despite the Biden team backtracking once in office, with Kamala Harris telling Central American immigrants “do not come,” border agents whipping migrants on horseback, increased roadblocks to asylum claims, and a continuation of many of Trump’s policies to varying degrees, people decided to depart for the U.S.…in droves.

Due to U.S. imposition of unfettered imperial neoliberal policies in Northern Triangle countries, Central American migrants who appear at the U.S.-border (if not caught and diverted by Mexico) largely come from Honduras, El Salvador, and Guatemala.

Nevertheless, U.S. intervention has also reached the shores of Nicaragua, not just with the U.S.-backed coup d’état in 2018, but with subsequent meddling and sanctioning that has made it more difficult for the Sandinista government to look after its people.

Far-right Florida Congresswoman María Elvira Salazar holding up photos of U.S.-funded coup leaders Felix Maradiaga and Arturo Cruz at a hearing on Nicaragua. [Photo: thegrayzone.com]

Moreover, due to U.S. political aggression against Nicaragua, Venezuela and Cuba, migrants from these countries seem to be treated more favorably than others at the U.S. border.

Consequently, and predictably, since 2018, Nicaraguan migration to the United States has increased after historic lows in the years prior due to economic growth and enviable social governance of the socialist-oriented Sandinista government.

Even in this context, the number of migrants from Nicaragua to the United States is smallcompared to overall immigration and from Northern Triangle migrants, in particular. Western media outlets admit that the apprehensions this year—that are part of longer emigration patterns since the 2018 U.S.-backed coup d’état—are at a historic high “since at least a decade.”

In fact, since the Sandinistas returned to power in 2007, border patrol “encounters” at the U.S. border “hovered” around only 1,000. Nicaraguans, in short, were not emigrating to the U.S. prior to the 2018 US-backed coup and their numbers at the U.S.-Mexico border now are very low compared to those of their Northern neighbors.

Paradoxically, the good governance of the Sandinista government meant low migration to the United States, precisely what the U.S. government claims it wants.

Should I Stay or Should I Go?

I’ve had informal conversations with some young adults in my town, on the outskirts of the city of Estelí, about emigration. Leading up to and including the summer 2021 (winter in Nicaragua), in the town where I live, some young people questioned: Should I stay or should I go?

In the surrounding communities, including my own, some young people did leave—about 20 in total, I am told. They constitute a very, very small percentage of the young people in my and surrounding towns. Whatever the exact (small) number, enough people have left for individuals here to know someone who left or heard about someone who left for the U.S.The increase in apprehensions into the summer 2021 by U.S. Customs and Border Protection is consistent with these anecdotal accounts. When I asked about the reasons emigrants decided to leave, these young adults tell me that emigrants left due to economic aspirations and difficulties.

NO ONE mentioned government repression, authoritarianism, fear due to their political leanings, or any other political reason, regardless of their political inclination. All of them tell me that the people who left did so because of economic pursuits and the belief that the U.S. president was letting everyone in.

It is important to point out that the people leaving tend to have enough money to pay for the trip, including the fees for a coyote. Some of the people who crossed successfully and are working in the U.S. usually have someone helping them settle.

Some of the people whom I spoke with also mentioned that they were considering or had considered leaving for the U.S. Again, they told me that they could probably make more money in the U.S. and it was unclear that they were going to make the money they desired in Nicaragua.

The reasons for deciding not to take the trip include: (1) not having money to take the trip; (2) family members do not want them to take the trip; (3) they thought about leaving because their friends had left and were doing well, but that, upon consideration, it was better not to do it—too risky or because they were doing just fine in Nicaragua.

Even among those who considered but did not actually leave for the U.S., “political repression” did not figure in their decision. The reports of difficulties on the way to the US, including deaths, also had a sobering effect on wanting to go North.

COVID-19 in Nicaragua Amidst Western Aggression

COVID-19 has exacerbated economic difficulties that stem from the 2018 U.S.-backed coup. Since the beginning of the pandemic, the Sandinista government of Nicaragua has engaged in a herculean effort to secure vaccines for its people.

Western aggression—coupled with Western greed—has limited vaccines for Nicaragua.

This summer was a tough one for families whose members came down with COVID-19, making people more worried. Economic desires/needs and COVID worries converged to pushed some to consider—and some to head for—the United States.

In my town, after a wave of vaccinations reached Estelí, the talk of heading to the U.S., however, waned. This is supported by data that shows a decrease in migration apprehensions at the U.S.-Mexico border later in the summer 2021. The latest wave of vaccinations in Estelí on Oct. 7th, as with the rest of the country, showed high demand for vaccinations. The Ministry of Health organized four points for vaccinations.

In all of them, people started making lines the day before to assure a poke. Experienced with the massive demand for vaccinations against COVID-19, the Ministry of Health started working and organizing the lines the day before vaccinations were to occur, handing out numbers so that people knew early whether they would be able to get vaccinated. They started vaccinating people at midnight the day of the announced vaccination, so as to not keep people waiting any longer. In a nearby municipality, San Nicolas, the wait times were much shorter.

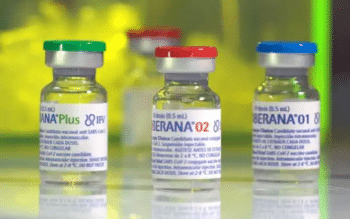

Just a couple of weeks later, the arrival of the Cuban (Abdala and Soberana 02) and Russian vaccines (Sputnik Light) designated to vaccinate children between 2–17 and those over 18–29, respectively, further allayed people’s concerns.

Later, more Sputnik V and Pfizer vaccines also arrived. Unlike the United States, the Sandinista government of Nicaragua is not pursuing vaccine mandates. Vaccination is 100% voluntary.Even without mandates, the demand for vaccines is high, which reflects the amount of trust that the population has for the government. Given the way the oligarchs and empire have used the pandemic to score economic and political points, including a marketing and media campaign against non-Western vaccines, among some more well-to-do people, there is a desire for “American” vaccines.

No doubt some in the Nicaraguan population have been manipulated with the ruse that “American” vaccines are “better.” Consequently, recently, some Nicaraguans went over to Honduras to get the Pfizer vaccine, having bought the propaganda. Western media outlets cynically and falsely reported that Nicaraguans deciding to get vaccinated in Honduras were doing so because of vaccine shortages in Nicaragua.

Nothing could be further from the truth. The arrival of the 1,200,00 Cuban vaccines in Nicaragua has increased access. One no longer sees the lines for vaccines we were accustomed to.Recently, the government announced the arrival of an additional 3,200,000 Sputnik Light vaccines. Importantly, the percentage of Nicaraguans who have gone abroad to get vaccinated, whether in Honduras, the U.S., or anywhere else, is negligible.

On Nov. 4, the Sandinista government announced that about 49% of the entire population (over 3 million people) have been vaccinated. Among the Nicaraguan working-class (most of the country), trust in the Cuban and Russian vaccines is equal to that of “American” vaccines. In fact, a few people whom I know that received Sputnik Light are even happier because it requires only one jab. Some of these working-class people speak about the “ignorance” of those who only want the “American” vaccines.

I personally know one case of an individual who decided to go to Honduras to vaccinate his 14-year-old child within days of having the option of vaccinating him with the Cuban vaccine. This individual’s mother—the child’s grandmother—died the day he went. He was unable to see her alive again.

There was another terrible case in which a couple of people were injured in a car accident on the way back to Nicaragua from Honduras after getting the vaccine. Recently, the Nicaraguan government returned about 100,000 Pfizer doses to Honduras, which had lent these to the Nicaraguan government in early October so that it could vaccinate pregnant women and lactating mothers. Vaccination initiatives are part of the very successful policies that the Sandinista government has implemented due to COVID-19.

Despite criticism and the lies on which it was based, the Nicaraguan government never implemented lockdowns, knowing that most of the population must work daily to provide for their necessities. In Latin American, people whose countries have enforced lockdowns have suffered dire consequences.

Economic elites have the option of taking a plane and going to the United States to get vaccinated, which is a widespread phenomenon throughout Latin America. The working classes do not have that luxury, so media campaigns against Russian and Cuban vaccines only hurt the most disadvantaged when they are swayed by the highly destructive Western rhetoric against non-Western vaccines, because they will be left without an option should they want to get vaccinated.

The United States knows that if it subjects Nicaraguans to material suffering through economic attacks such as the NICA Act and the RENACER Act (approved by the House of Representatives on Nov. 3), some people will undoubtedly blame the Sandinista government for their individual economic suffering.Already, some Nicaraguans do blame the government for their stagnated economic well-being, either unaware of the attacks the U.S. is launching or propagandized to minimize their importance.

Elections, Western Aggression, and Migration: An Old Story with a New Virus

Despite economic suffering generated by the U.S.-backed coup d’état in 2018, which was subsequently exacerbated with COVID-19 and Eta and Iota hurricanes, emigration to the United States is not as widespread as reported, certainly much lower compared to emigration from the Northern Triangle.Nicaragua accounts for only 3% of the total apprehensions at the U.S.-Mexico border this year thus far. The emigration of the Nicaraguans that do leave stem from mostly economic causes, which can be directly traced to the 2018 U.S.-backed coup—difficulties that the worldwide pandemic and natural disasters has exacerbated.

Uncertainty associated with U.S. threats of economic unilateral coercive measures if the FSLN wins the presidential elections is no doubt another “push” factor for those who remember the economic blockade the U.S. imposed on Nicaragua in the 1980s and its disastrous consequences.

U.S. Sanctions emptied the shelves at supermarkets in Nicaragua in the 1980s. [Photo: havanatimes.org]

Importantly, all of these challenges in Nicaragua have not considerably dampened support for the Sandinista government. The latest poll, released on Nov. 3, 2021, just days before the elections, articulates, once again, massive support for the FSLN with Daniel Ortega’s leadership and predicts an easy win for the FSLN coalition.

The only “crisis” in Nicaragua is the one the U.S. and its imperial lackeys want to inflict upon the country. Without a single vote cast, the U.S., the European Union and Western media—and some U.S.- and Western-controlled international organizations—have already dismissed the upcoming election as a “fraud,” despite there being five opposition candidates on the ballot running against Ortega.

By the looks of it and their announced plans, the United States and their allies will work hard to delegitimize the Nicaraguan elections and subsequent FSLN win at the ballot box. They have spared no regime change effort against the Sandinista government in Nicaragua.

For example, just days before the election, Facebook, Instagram and Twitter suspended the accounts of pro-Sandinista journalists and activists with the lie that the accounts were generated by “a troll farm run by the government of Nicaragua and the [FSLN].” The people who were censored have spoken out against this attack, which they suffered simply for being Sandinistas or supporting Sandinistas.

U.S. agents have misrepresented and exploited land disputes in Nicaragua’s autonomous Indigenous territories to the UN Human Rights Council and the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights.

In a bizarre turn of events, judging by apocalyptic Western media reports and U.S. (and some European) politician rhetoric, the Nicaraguan election seems to be much more of an alarming and consequential event for Western elites than for Nicaraguans who, for the most part, want to continue leaving in peace, building their lives on the rights and privileges they have grown accustomed to since Sandinista returned to power.

A U.S. citizen would be astounded at the amount of support that the Sandinista government provides to its people, especially because in the United States, policies enacted by the government represent, to an exceeding degree, the interest of its elites.

Among its initiatives, the Nicaraguan Sandinista government has launched Vivienda Digna, Hambre Cero, Usura Cero as well as others that reduced poverty.

Sandinista anti-poverty initiative that provides training to workers to help them get jobs. [Photo: tecnacional.edu]

The achievements of the Sandinista government over the past 14 years have yet to be fully catalogued and recognized. The achievements with regards to public health have been truly astonishing, and great strides have been made in other domains, including public education, electricity and clean water access, housing for the poor, support for small and medium businesses, treatment of its indigenous communities, food sovereignty, and many, many more.

Of course, these achievements are never reported in Western media because they contradict the “dictator” narrative against Daniel Ortega that the United States and its allies use as part of their multi-pronged effort to destroy the socialist-oriented, highly successful FSLN government.The U.S. and their lackeys are trying to tapar el sol con un dedo— block the sun with one finger!

But the achievements of the socialist-oriented Sandinista government, while fuzzy for a Western audience, are crystal clear for Nicaraguans, especially its working class (most of the population).

The expected, resounding victory of Daniel Ortega from the FSLN coalition is not a function of authoritarianism, but a consequence of the work the Sandinista government has done for the Nicaraguan population and the trust they’ve garnered as a result. One project at a time.

Yazer Lanuza is a professor of sociology at the University of California, Santa Barbara. Dr. Lanuza’s research examines the causes and consequences of social inequality in three domains: education, family and the criminal justice system. He focuses largely, though not exclusively, on the experiences of immigrants and their offspring from Latin America and Asia.