At a National Security Council meeting in September, U.S. Secretary of State Anthony Blinken said that the consequences of climate change “are falling disproportionately on vulnerable and low-income populations.” He continued, “And they’re worsening conditions and human suffering in places already afflicted by conflict, high levels of violence, instability.” He assured his colleagues that the climate crisis is a “core element of U.S. foreign policy” and that “every bilateral and multilateral engagement we have–every policy decision we make–will impact our goal of putting the world on a safer, more sustainable path.”

Download the full report on TNI’s website.

Blinken’s sentiment was echoed by a report on the impact of climate change and migration from the White House earlier this month, one of a slew of reports as the U.S. prepared for the United Nations summit on climate change that began in Glasgow on October 31. According to the report, “The current migration situation extending from the U.S.-Mexico border into Central America presents an opportunity for the United States to model good practice and discuss openly managing migration humanely, [and] highlight the role of climate change in migration.”

Hypothetically, these words might reassure the more than 1.3 million Hondurans and Guatemalans displaced in 2020 by climate-induced catastrophes such as droughts, hurricanes, and floods. But the lofty rhetoric is contradicted by another story, one told by the U.S. government’s budgets.

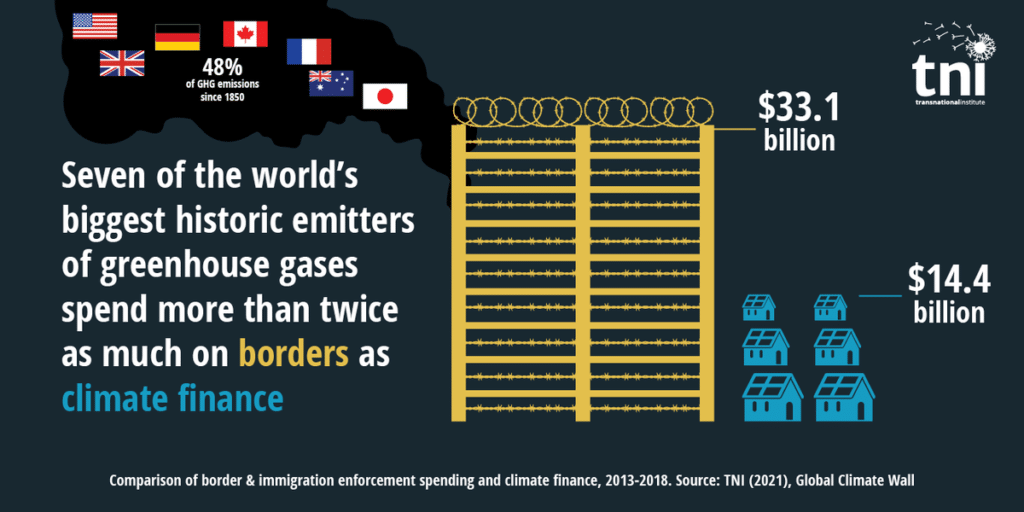

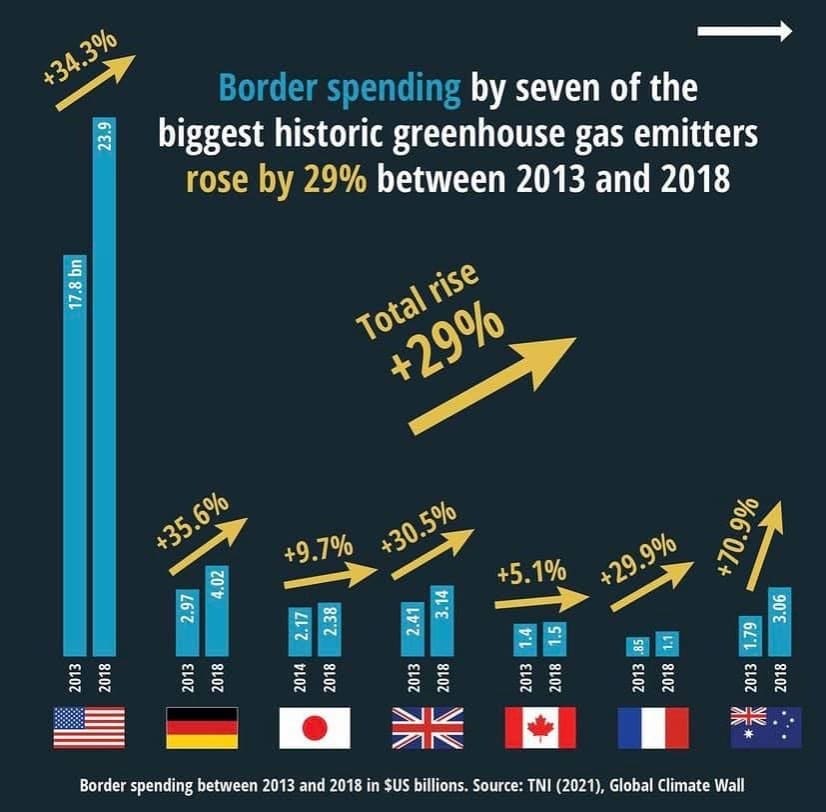

In a report titled The Global Climate Wall, which I co-authored for the Amsterdam-based Transnational Institute, we crunched the budget numbers for seven of the countries most responsible for the climate crisis. These countries collectively account for almost half the world’s greenhouse gas emissions going back to the mid-19th century. They include Canada, Australia, the United Kingdom, Germany, France, Japan and the United States (which led the charge at 30.1 percent of emissions). All together, these rich, high-polluting countries spend more than double on border and immigration enforcement budgets than on “climate finance”–that is, helping vulnerable countries adapt to climate change and transition to clean energy.

While the White House report does emphasize foreign aid (to note, advocates refer to the report as “disappointing”), it does not mention that the U.S. has dedicated 11 times more money to militarizing its borders and building up a draconian immigration enforcement system than to climate finance. And while the U.S. has the world’s largest border budget (an average $19 billion per year from 2013 to 2018, and an almost 11-to-1 ratio of border to climate financing), Canada (15:1) and Australia (13.5:1) have even higher ratios. In no way is the United States, or most other countries, “managing” immigration “humanely.” Precisely the opposite.

All together, the world’s largest polluters are compounding one human-made disaster with another one. They are constructing a world of more than 63 border walls, with tens of thousands of border guards, and spending billions on technologies that blockade and criminalize people in desperate situations rather than assist them. More than 44,000 people (a vast undercount, according to researchers of the International Organization on Migration) have died crossing borders from 2014 to 2020, in both the world’s deserts or seas. And tens of thousands of others are incarcerated in a global network of more than 2,000 detention centers, while companies in the border industry anticipate more contracts in a roiling, intensifying climate crisis. The company G4S, for example, told the Climate Disclosure Project in 2014 that the UN “projected that we [the planet] will have 50 million environmental refugees,” which could offer investment opportunities.

As G4S surmised, climate-induced displacement and migration are already underway and are expected to increase. Not only are there more frequent and intensifying storms and floods that come quickly and recede, but there are also slower-onset disasters, such as desertification and sea level rise, that leave irrevocable damage and render places uninhabitable. The Internal Displacement Monitoring Center estimates that nearly 25 million have been displaced yearly since 2008. These numbers will only get larger in a “business as usual” scenario in which 19 percent of the earth’s surface–inhabited by nearly one-third of the planet–will become a “barely liveable hot zone” by 2070.

A decade ago, another report, titled In Search of Shelter, one of the first empirical studies linking climate change and displacement, warned that in the status quo “the mass of people on the move will likely be staggering and surpass any historical antecedent.” A decade later, this warning appears to have gone unheeded.

To respond to this with increased border fortification is to create a dystopian catastrophe. As with greenhouse gas emissions, we have to reduce barriers, surveillance drones and high-tech cameras. One way to do so is to move money from border and immigration enforcement into climate financing.

The seven countries profiled in The Global Climate Wall were among the world’s richest countries that committed to collectively contribute $100 billion by 2020 to climate financing at the UN climate summit in Copenhagen in 2009. But since then the money has fallen short. In any case, many, including the Group of 77, argue that the $100 billion goal is inadequate to confront the scope of the crisis. Moreover, climate financing is most often dedicated to building stationary resilience, such as sea walls, new resilient crops to withstand drought and infrastructure to deal with flooding.

But climate financing needs to be extended to assist people who are displaced and forced to move in this intensifying ecological catastrophe. In other words, precisely the opposite of building more border walls. Finance could be directed to assist in moving costs or to helping build up infrastructure in places where people are moving, most often cities within the same country. Even the mealymouthed White House report says that “migration is an important form of adaptation to the impacts of climate change and in some cases, an essential response to climate threats to livelihoods and wellbeing.”

A global demilitarization of borders could free the finance needed to make this happen. In the report we wrote, “This divestment and investment could alleviate the incredible suffering and death inflicted by the current border system and make it easier for people to stay close to home.” This certainly would be one step to creating the safer, sustainable world that Blinken mentioned.

The Department of Homeland Security, however, has other plans. In reports it released this month on climate change, DHS lays out its strategic framework:

Climate change impacts extend far beyond melting sea ice, with strong implications for security of our borders, the health of the rules-based order, and America’s way of life.

It continues: “Climate change impacts have the potential to reshape the mission of DHS for the foreseeable future,” including “proactive actions to manage future border crises.”

The U.S. government, then, is at odds with itself. The White House projects a lofty rhetoric of environmental justice; congressional budgets maintain the status quo; and the border cops and industry, unsurprisingly, clamor for money. As the global environmental movement prepares to keep a close eye on the upcoming UN climate summit in Glasgow, the question remains whether popular demands for justice–for defunding borders and for funding climate action–will be heard.