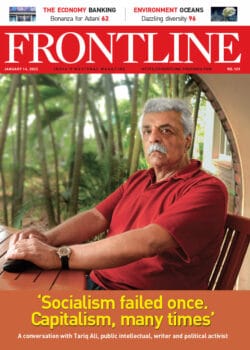

We are grateful to Frontline (India) for allowing our readers access to the following interview, which is the cover story of the January 14, 2022 issue. We encourage our readers in India and elsewhere to support Frontline by purchasing a subscription.

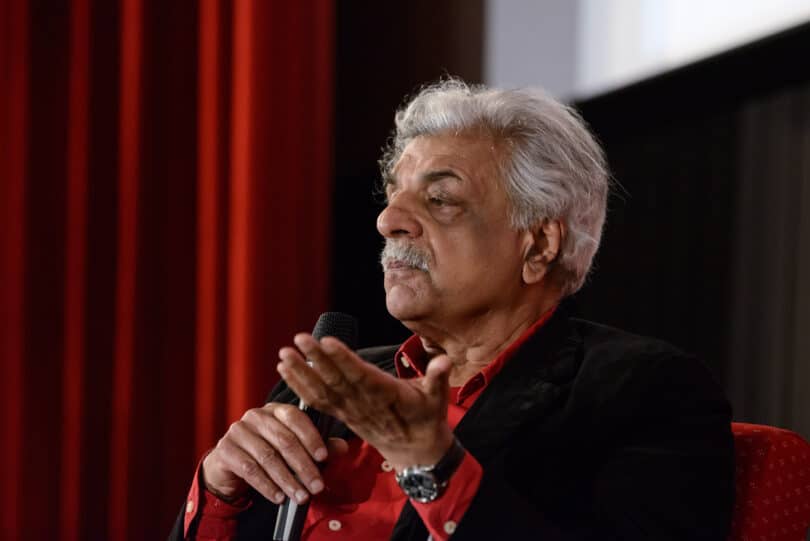

Jipson John and Jitheesh P.M. interview Tariq Ali—public intellectual, writer and political activist

Tariq Ali is an internationally known public intellectual, columnist and political activist. Born in pre-Partition India in 1943, Tariq Ali studied at Oxford University and was elected as students’ union president there. He has been involved in political activism since then. He was one of the most prominent figures of the civil society coalition against the United States’ war in Vietnam. He was also there at the forefront of agitations against the wars in Afghanistan, Iraq and elsewhere

A well-known columnist contributing to leading dailies such as The Guardian, Tariq Ali has been associated with the New Left Review magazine for over 50 years. Among his important non-fiction writings are The Forty-Year War in Afghanistan: A Chronicle Foretold, The Extreme Centre: A Second Warning, Street Fighting Years: An Autobiography of the Sixties, Pirates of the Caribbean: Axis of Hope, The Clash of Fundamentalisms: Crusades, Jihads and Modernity, The Leopard and the Fox: A Pakistani Tragedy and An Indian Dynasty: The Story of the Nehru-Gandhi Family. He has also written fiction: the Islam Quintet comprising Shadows of the Pomegranate Tree, The Book of the Saladin, The Stone Woman, A Sultan in Palermo and Night of the Golden Butterfly.

In this interview, Tariq Ali, the anti-war “hero” of the 1960s, reflects on some of the most important issues of our time: the situation in Afghanistan, the Western powers and the “war on terror”, political developments in Latin America, causes of the worldwide right-wing upsurge, the changing media landscape, the potential of new media, digital surveillance and democracy, the challenges before the Left movements, contemporary capitalism and the poor, lessons from the COVID-19 pandemic, and so on.

The Afghan mess

The U.S.’ longest fought war has just ended in Afghanistan. Twenty years ago, the U.S. entered Afghanistan with promises such as removing the Taliban from power and establishing democracy. By 2021, lakhs of people, mostly innocents, had lost their lives and the U.S. had spent more than $2 trillion on the war. But the Taliban is again in power. How do you look at these developments?

The first point is that what we are witnessing in Afghanistan is the defeat of the world’s largest and only imperial power. It is not just a military defeat. We have to stress that point. In the case of Afghanistan, it is certainly a political and an ideological defeat for the U.S. It is also a defeat of the U.S.’ imperial projects shared with the Europeans through NATO [the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation]. This fact is a shock, especially to liberals, who have never been able to accept that imperialism did collapse.

The second point is that the Taliban was the only force, whether you accept it or not, in Afghanistan that decided to fight [against]… the occupation. It would be extremely sectarian of anyone on the Left or the liberal Left to say that we don’t like it because this is the victory by the Taliban. To this argument, these questions have to be asked, Were you there? Why did you not fight? Why did you not march on the streets against the occupation of Afghanistan? Did you really believe that NGOs [non-governmental organisations] handing out money for the training and education of some women in a few cities was going to [bring about] a structural transformation of that country? If you believed it, then you have been proved completely wrong. Nobody thought that the Taliban could win, but the hard fact now is that they have won.

NATO and the U.S. could not deliver their “professed” goals in Afghanistan. They ran an outfit in that country for 20 years which was characterised by some of the worst examples of neoliberal capitalism. It ultimately created a small elite backing the occupation and making money. This was no secret. The Afghanistan papers published by The Washington Post made this aspect clear. American diplomats, generals and ideologues spoke openly about how this war was becoming disastrous. Some of them said [what] many of us were already saying, that the Hamid Karzai government, which has been praised throughout the Western press, was nothing but a bunch of corrupt politicians making money. Now you read in the Washington papers and an official federal report by the U.S. government that Karzai was never anything else. All he created was a kleptocracy. Many of the criticisms we were making were correct.

What about the issues faced by women? When the Taliban first came to power, it was harsh and cruel in its approach to women. Many people have similar fears now. Women’s emancipation also was one of the proclaimed objectives of the U.S.-led “war”. What is your take on this?

One of the most important questions on Afghanistan, which has been highlighted not only today but during the U.S. invasion also, is what about women? To which I ask, you were there for 20 years and what did you [Western powers] do about the condition of an overwhelming majority of Afghan women? Of course, I fully defend the rights of women. I’m not talking about the small groups of women in Kabul or in a few other cities. I’m talking about the whole of Afghanistan. Half of the women are under the age of 25. What did you do about them? Now you are complaining when the Taliban is back in power. But, did you change their condition when you were in power? The answer is No. Initially, they [the Western powers] projected the war as one against terrorism and as the struggle for women’s liberation. This is what Mr [Tony] Blair and Mr [George W.] Bush told the world. But what is the balance sheet after years? How many [women] have you educated? How many schools have been built? How many teacher training colleges have been created for women? The answer is either none or very few.

I would add another point to this. The condition of women, according to some of the women activists I’ve spoken with, actually became worse under the Western powers. More and more women were dragged into becoming sex workers secretly. Because they were scared of their families. Sex workers were imported from other parts of the world too. Brothels were created as they were during the Yugoslavia war. What did this say about the condition of women in Afghanistan? In my opinion, the major change was the encouragement of sex work and the building of brothels, either private or public. The Taliban was extremely backward in their approach to women. But under them rapes were decreased because they used strong measures against rapists. Their punishment for rapists was either kill them in some cases or castrate them. I do not approve of that way of dealing with the problem. But in any case, the figures were relatively low. What are the figures now after 20 years?

Is the condition of women in Afghanistan worse than the condition of women in other countries of the region? I would say that it is roughly the same. Structurally, it may be different. Even in countries where you have laws that proclaim gender equality, what are the figures? What is the education of poor women in Pakistan and India, the two neighbouring states? Not that much different, I would say. Who gets educated [in Afghanistan]? It is in the cities of Afghanistan, basically urban women who constitute most of the educated women. That is fine. But it does not answer the problem.

It is to be noted that on the question of gender, not Afghanistan alone but the entire region has to be considered. The Western powers don’t want to do that because gender is now becoming a prime weapon, an ideological weapon, to be utilised against the group that defeated the U.S. This is the situation in Afghanistan.

What helped the Taliban capture power when the other side was the world’s largest military power on the offensive?

It is the result of a complete failure of the U.S. to create any alternative political, military or state structure. And the puppet army of 300,000 people collapsed easily. Some of them went on to become refugees. Some refused to fight against the Taliban. Some joined the Taliban and handed over their weapons to it. The police force also collapsed. A quarter of the police force was busy making money from the sale of drugs. A quarter of them, if not more, were Taliban infiltrators. When the American occupation began, the Taliban decided to not resist it militarily. They shaved their hair and rushed to hide in Pakistan or within the mountains of Afghanistan. And they started becoming active again as the Afghan people began to see the real nature of the occupation.

There was virtually no resistance against invasion from any progressive forces inside Afghanistan. One has to be ashamed to say that most of the progressive forces in Afghanistan, including the former PDPA [People’s Democratic Party of Afghanistan] members, backed the U.S. intervention. So they had no credibility whatsoever. Had there been one progressive organisation in whatever part of the country resisting [the occupation], the situation would have been a bit more balanced. But there was none. The Northern Alliance completely worked with the U.S. As occupation was totally dependent on the Northern Alliance, how can it be presented now as an administration that tries to help women? There is an Afghan feminist in exile who said in private that we had three enemies: occupation, the Northern Alliance and the Taliban. And she says now we have only one enemy.

One has to resist the flow of imperialist propaganda which tries to cover up the total and abject failure [of the West] by saying now, “Oh, look what the Taliban are doing to the women.” These people are never interested in the question of women’s emancipation when their own interests are not involved in any manner. If they were genuinely interested, then they would see the women’s question not just as an Afghan issue but as an issue affecting the entire region. They are not doing that.

What will be the future of Afghanistan under the Taliban?

I would say that when the U.S. is defeated, whether it’s in Vietnam or in Afghanistan, they punish that country. Vietnam received no reparations. Their entire ecology was destroyed by the use of chemical weapons. Napalm was used against the civilian population. When I was in Vietnam, I saw children’s backs burned, faces made into the faces of monsters by the use of napalm. What will they do in Afghanistan now? We have to see the hard reality underneath the 20 year’s occupation mask. The reality is that nothing much changed in the country except for the elites and for the collaborators of the West. The Western powers are imposing sanctions on Afghanistan and threatening to roll back all aid. It’s a monstrous crime taking place against that country. First the Russians invaded that country, which was wrong and led to this mess. For 40 years, this country and its people have known nothing but war. We have to think of the impact this has on children. Kids have grown up knowing nothing but war. It is not just about the psychological impact, but every family lost members all over the country. That’s the situation in Afghanistan.

For the sake of the people of Afghanistan, what we could say to the West is that do not go for sanctions. Sanctions and blocking aid never had any impact on any leadership. Instead, they are punishments for the people. Sometimes, the Americans do it deliberately as they did against Iraq where half a million children died during the sanctions. This was even before they invaded that country. The rationale behind the sanctions is that if we [impose] sanctions on the country, then people will suffer, and there will be an uprising to topple the government.

But the reality is that suffering people blame not their own regime but those people who are inflicting the suffering. People know who is doing all these things. This tactic did not work in the Arab world. It has not worked in Venezuela where all these things are going on at the moment. It will not work in Afghanistan. But it will make people’s life more miserable.

Whether the Taliban changed or not over 20 years is another discussion. It should be understood that the generation that has grown up over the last 20 years in Afghanistan is a generation which consumed different news bulletins on their cell phones or on their computers. This means that people, in general, are better informed than they used to be. Given that the bulk of the population of Afghanistan is under 25, we will see how they will react. But one thing is sure: very few Afghan people want the civil war back.

What are the geopolitical implications in the region with the Taliban assuming power?

First, on the question of the geopolitical nature of what is happening in Afghanistan, what we could say is that we are now living in slightly different times. Today, the second major power on the globe is not Europe or the European Union [E.U.]. It’s China. China is in Asia. The Chinese market economy has grown phenomenally. The fact that China has borders with India, Pakistan and Afghanistan means this state will play a big role in the next few years in the geopolitical developments in the region. And the Taliban leaders are well aware of this. That is why the first foreign delegation from the Taliban did not go to Saudi Arabia but flew to China for a meeting with the Chinese Foreign Minister and other senior officials. They gave a firm assurance that they were not interested in any interference in Xinjiang. It seems that the Chinese are pleased with the talk.

The second thing is the Taliban’s changed relation with Iran. Its relation with Iran was very bad. This was largely because Sunni fundamentalism was used against the Shia community in Afghanistan. But over the last six or seven years, there have been numerous talks with Iranian leaders, and some element of reconciliation has taken place. The Iranians are not interested in destabilising the new regime. There will be no encouragement of a civil war by the Iranians also.

Third, it’s not impossible that the Taliban will even learn some lessons from the Iranians on how to run a country. To have a likely Iranian model to permit elections in which real candidates, not bogus candidates, contest [against] each other reflecting different opinions will be a step forward. I think there is some indication that the Iranian model is being considered as a possible constitutional model for Afghanistan. It’s very early now to speak with any confidence about what might happen over the next year. With Pakistan, the Taliban’s relations are very close. Very close but also not as fully friendly as people might imagine. Even during the last year of the previous Taliban government, there were tensions opening up. But there is no doubt that the Pakistani military has helped the Taliban over the last 20 years. That itself is interesting. Pakistan is the country which has been a long-time ally of the U.S. But on the other hand, the same country has been providing aid and strategic help to the Taliban.

Do you think that Afghanistan will become a hotbed of terrorism now that the U.S.-led forces have withdrawn? What about the operations of the Islamic State (or ISIS) and other terrorist groups?

The Islamic State has already gone into Afghanistan and built their base there. They are not in favour of the Taliban. In fact, they are fighting the Taliban, saying that the Taliban should have no negotiations with the U.S. The history of ISIS, both in the Arab world and in Afghanistan, is that they never ever targeted imperialism or its alliance. They target other Muslim sects or minorities like Christians. This is what they have been doing. Inside Afghanistan, they have been attacking the Taliban by and large. I am told that the Taliban captured ISIS leader Omar Khorasani … and killed him quite brutally. It was to avenge the capture and execution of Khorasani that the Islamic State [carried out an attack at] the airport and for the first time killed any American there. I think that the Taliban will have to deal with them. It would be a big tragedy if these Islamic State people become an opposition force in any form. Their strength is largely in the Pashtun area of Afghanistan. They might spread and they might make the opportunistic link-up. This would be a tragedy for Afghanistan. So ISIS is there but certainly not near to power.

A history of defeating occupiers

Many people forget that Afghanistan gave women voting rights in 1919, much before many Western countries, including even Britain. What led to Afghanistan’s contemporary fate?

To understand Afghanistan’s structure, we need to see how it was self-created as a tribal confederation. Different tribes were united to create a country known as Afghanistan. And they fought any attempt to curb their independence. There was a huge war fought by Afghan tribes against Aurangzeb’s attempts to subdue them. Aurangzeb sent his army led by Hindu, Muslim and Sikhs generals. Sikhs and Hindu generals always formed a key part of Mughal armies, and the resistance came from Afghans and they defeated one of Aurangzeb’s armies. Subsequently, when the Mughal emperor collapsed, Afghans themselves became very dominant.

During the British period, this trend continued, and the British fought three wars in Afghanistan. They were defeated in the first war. It was a crushing defeat for the British Empire. Afghans suffered blows from the British in the second war. But they managed to defeat the British in the third war. As revenge for the defeats, General Pollock ordered the destruction of the old medieval bazaar in Kabul. It was an artistic work of great beauty. To punish people, you destroy what they love, like and respect. The way the British dealt with the Afghans was based on a theory of vicious racial imperialism. If you look at the dispatches that were sent, including those by [Winston] Churchill, that is very clear. And also look at some of [Rudyard] Kipling’s verses.

I was just doing some additional research for my new book on Afghanistan. And I discovered a dispatch written by a senior British Raj civil servant to the Governor of Punjab in which he refers to Afghans as savages, and they say that some of them may be noble savages but the fact is that they are savages. Afghanistan is a country which produced some of the most amazing works of poetry. Khushal Khattak was writing in the 17th century. Poems attacking the Mughal emperor and defending Afghans, lyrical poetry, love poetry, political poetry, etc., were produced from this region. Calling the people of the region “noble savages” shows the incapacity of the Western empire to understand real history.

The October Revolution of 1917 in Russia had a huge global impact. The first decrees of the Bolshevik government were astonishing, saying freedom to all the colonised countries which are brutalised by imperialism, freedom in particular to all the Muslim world forced to live under the imperial yoke of the tsar, etc. One of the early decrees proclaimed by the Bolshevik government reached Amanullah Khan, the ruler of Afghanistan, and he was impressed with it. At that time, the Turkish nationalists had not replaced the caliphate yet. The nationalists had gone for the modernisation of Turkey and gave women equal rights. The combination of Lenin and Mustafa Kemal Atatürk had a huge impact on Afghan elites. Amanullah sent messages of support. Afghanistan prepared its own constitution in 1919 in which women were granted full equal rights. This was seen by them as an anti-imperialist act.

The British then intervened in Afghanistan and basically destroyed the Amanullah government. A campaign was waged against Amanullah and Queen Soraya. This was led by tribal reactionaries but backed, armed and funded by the British Empire. This was similar in some ways to the jehad waged by [U.S. President] Jimmy Carter against the USSR [Union of Socialist Soviet Republics] in the late 1970s and 1980s. So Afghanistan has a long history of imperialist intervention. Every single time, it has succeeded in defeating the occupiers, from the Mughals to the British, the Russians and, now, the Americans. This is quite deeply embedded in the historical memory of the people in a country where literacy is still not universal.

The Xinjiang option

Will the Western powers or the U.S., in particular, learn any lesson from all this?

No. They never learned any lessons from all the setbacks and defeats they suffered in the past. The only time they learn is when another empire begins to challenge them. The U.S. embarks on a crazy mission to try and destabilise China from within. The Taiwan option is not so favourable for them. The Hong Kong option is also more or less finished. The only option the U.S. has is to arm and unleash the Uyghurs in Xinjiang. I am told that there are thousands of men in Turkey being trained and armed by the Turkish government on behalf of the U.S. [Turkish President] Recep Tayyip Erdogan is using some of them in the wars against his enemies in the region, especially in Syria. Turkey is an important player now as the U.S. relies on it, but it also sometimes opposes the U.S. to defend its own limited interests.

If the U.S. uses this against the Chinese in Xinjiang, not because it knows it will win but just to get the Chinese occupied with other things, it could lead to a situation that the Americans do not predict and can’t predict. It’s a risky adventure. That is why I’m perfectly aware that the Chinese policies towards their national minorities are not something that anyone on the Left can learn from. It’s a very hard and centralised state that the Chinese have created. No doubt that the Chinese do things that one cannot support. However, when people start characterising what is happening in Xinjiang as genocide, that makes me nervous. I think it’s wrong to characterise it like that. These days, any country which does something the West doesn’t like is characterised as genocide and often linked for possible military intervention and occupation. There have been genocides in various parts of the world, of Jews, of Armenians, of Rwandans, etc. But again in all these three actual genocides, the West did nothing to protect people.

Small massacres are indefensible in any sense but to characterise them as genocide has only one real function. That is why the U.S. is unlikely to learn any lessons from Afghanistan.

After 1975, the shock to the U.S. system was great because its own army people were dissenting against the occupation in Vietnam. Thousands of soldiers and veterans demonstrated outside the Pentagon and declared that they hoped Ho Chi Minh and the National Liberation would win. When that happens inside your own imperial army, it gives you a shock and you have to sit back and take notice of it. But they did not delay for too long before another intervention. The Contra was started by Ronald Reagan to destabilise the regime in Nicaragua in the late 1970s. Just four or five years afterwards, it was business as usual in South America and some other parts of the world. The defeat in 1975 was huge. They accept that the defeat in Afghanistan is a setback, but they write it off as one of the things that can happen when you are a big empire.

Even if one opposes the U.S.’ attempts to bring about regime change in another country, one has to accept that authoritarianism is a reality in many parts of the world. How would democratic transition come about in these places? What is your reading of the current world landscape?

My take is that only people in the country concerned can bring about real changes. If it’s done by outside powers, it never works. That is just plain common sense. Do we have freedom and democracy in Iraq after the war? No. We have nearly a million and a half people killed. Did the U.S. intervention bring freedom and democracy to Syria? No, and never will do. Did the overthrow of [Muammar] Gaddafi in Libya create a flourishing democracy? No. They imported a Libyan businessman who has been in Alabama for decades making money. They made him Prime Minister. He didn’t last too long. In fact, he lasted such a short time that few Libyans even can remember his name. Instead, what they provided the Libyans with were three jehadi factions fighting and killing each other. The policy of the U.S. seems to break up the Arab states. So the destruction they have inflicted on the Arab world is the biggest change brought about to the world since the First World War. Since the Arab world was taken away from the Ottomans, it has been transformed into tiny little states created mainly by the British and later by the U.S. They are now destroying that world.

The only real way to remove corrupt and capitalist regimes led by elites who have no respect for their own people is through movements from below. That is what is happening in South America. But they are constantly under a challenge from the U.S. The imperialist attempts to crush the Left progressive forces have not fully worked. The recent victory in Peru of the teacher President is a sign of that. The defeat of the pro-American forces who toppled Evo Morales in a coup earlier, in the 2020 election in Bolivia, is a good example. What the Bolivians said is that even though our leader was got rid of and exiled, we can win without him because we have created a strong institution.

In Asia, there is China, and I have already discussed it. In South Asia, you have India which is technically and constitutionally a democracy. The present government in India is utilising its own ideology to bring about a transformation and completely break with the Gandhi-Nehru consensus that ruled the country earlier. So, [Prime Minister Narendra] Modi has created a consensus such that even those opposed to his party are basically falling into its lap. These parties may maintain their own political structures, but there is increasing similarity in their language, the way they speak, the way they promote similar ideas, etc. In my view, among the two main opposition parties in India, the Congress party has become a joke now. To expect any vaguely radical thing from it is a joke. It is fighting a war for power. On the other hand, the Left in India is the weakest [it has] ever [been] in its history. When the Soviet Union collapsed, the mass communist parties of Italy and France collapsed. In India, this was not the case with the CPI(M) [Communist Party of India (Marxist)]. It managed to keep its hold in Kerala, West Bengal, Tripura, and bases in other parts of the country. And many intellectuals were still linked in some capacity to the CPI(M). But the total wipeout in Bengal is an indication that this party is on the decline. One can’t get away from this fact. The question is, can something be produced to move a large number of people who really need a movement forward? It remains to be seen.

Within the Korean Peninsula, nothing is going to change very much. Japan is still dominated and controlled by the U.S. It’s not even committed to a foreign policy of its own, and internally its politics are dominated by the elites who hang up in different parties. Socialists and communists hardly exist in Japan.

In South America, the combination of mass movements and left social democracy has emerged. They posed no big challenge to capital except regulation of capital. Domination of capital remains complete. As a result of this domination, the whole opposition in these countries is in the cocoon that has been created by capitalism. The real needs of the people are not dealt with. Then you had two huge events. First, there was the 2008 crash, the Wall Street crash. That was an opportunity for capitalists to actually transform it a little bit as they did after the Second World War, including some reforms. But they didn’t do it. The second big event was the pandemic. Ironically, the pandemic has forced a slight shift from neoliberalism to state intervention. But the status quo did not create hope among people. They do not want to create that because people will get overexcited, and they might want more which they cannot give them and cannot be delivered.

At the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, many people believed that a better world would emerge out of the crisis. During the crisis, millions suffered job losses, salary cuts, and so on. But even then certain billionaires made astonishing wealth. How do you look at the political, economic and social developments that happened around the pandemic?

“Another world is possible” is always true. It is the Right that attempts to create another world. The Left is by and large very weak but the Right is far more successful. [U.S. President Donald] Trump was a huge victory for the Right in terms of his actions to create another America, a white supremacist America. So for the Left, it is a more difficult slogan.

“We are the 99%” is a slogan put up by an advertising agency packed with left-wing sympathisers. The argument that 1 per cent of people control the wealth created by the 99 per cent was never too convincing for me. Because within that 99 percentage, there were hundreds and thousands of people whose real wages are different from the poor and starved. It is not a convincing slogan. Also, there is a social gulf within the 99 percentage. As far as I am concerned, yes you are against multibillionaires. That doesn’t exhaust the number of people who are earning salaries which were way far off the earnings of the 50 percentage of the population. That is why I am maintaining the position, in large part of my life, that however effective the sloganeering, it is never sufficient. How the world operates through the premises of politics and economics is important to understand. The question is about the transformation of social structures. It is about transforming the social structure of a country with mass support and with the creation of democratic institutions like new constitutions and parliaments based on new constitutions. That model given by the South Americans was not a bad one. The mass movement in Chile is working now on a new constitution. So the combination of these tactics will move the Left forward again. It is not a question of mimicking for existence. You have to think creatively and in new ways if you want to get rid of the present debacle. The question is, how many people want that?

The social and economic structure of capitalism today, like in the past, has a number of institutions to depend on. In this age of finance capitalism, which dominates the world, the political classes are in total alliance with these people. After the 2008 crash, a decent social democracy would have [said] that we will not allow this to happen in future. But they didn’t do that. But the pandemic has made them think. Some of the policies of [U.K. Prime Minister] Boris Johnson has shown how the state can be used for the benefit of the majority if it wanted to. The fact that it needs a virus disease to push it in this direction is distressing about world we are live in.

The Left, the Right and the vacuum

You have earlier said that the 2008 financial crisis created a vacuum that provided the way for the growth of the extreme right wing. Why did liberal or left politics fail to fill the vacuum?

First, there was a very interesting television appearance after the 2008 financial crisis in the U.S. I think it was Robert Reich, a democrat who served in [President] Bill Clinton’s government. An issue was put before him: after the Great Depression the U.S. government under Franklin D. Roosevelt pushed through heavy state intervention to create employment and look after its citizens, whereas nothing similar was done in the 2008 crash. To this point, Reich replied that at the time of the Depression you had the Soviet Union. We have to think about that. If we don’t do something, our workers would turn Left.

My thinking is that these words raise the real element of truth. Second, most of the bankers who got away in 2008 with cheating were not [put on] trial or punished at all. They were corporate criminals. President Barak Obama made a firm decision to stay with Wall Street and not to do anything. Movements from below, like the Occupy movements, were limited in their agenda and approach. Look at the huge occupation movements in the Middle East [West Asia] where the demand was effectively pro-democratic but nothing else. There was no demand for Arab solidarity, there was no mention of the Palestinian cause in most cases. Tahrir Square protesters underestimated that ultimately politics will come out. I remember talking to Egyptian friends at that time, and I said to them that the only big and organised opposition party in Egypt is the Muslim Brotherhood. If you people create nothing and think that things will happen spontaneously, then you are going to get a shock. Later, the Brotherhood came into the movement and won the next election, defeating the old regime but did not have alternatives to that regime. So the lack of political alternatives, even left-democratic alternatives, at that particular time created a great vacuum. An attempt to create a New Deal or recreate a New Deal came from [Senator] Bernie Sanders in the U.S. and Jeremy Corbyn in Britain recently. Jeremy Corbyn did win over the Labour party but is now suspended from the party. Anyway, these people did try, but they still need to reach too far.

Third, state powers didn’t particularly want to make so many concessions to people from below. They also felt that they do not need to do that as there was no huge pressure on them. So they didn’t give many concessions to the people from below. But I always feel that one country where something could have been organised by political forces was in India where the CPI(M) has hundreds and thousands of members and supporters. Instead of sticking rigidly to parliamentarism, it should have begun to organise people from below. Maybe it was difficult. The main reason that Mamata Banerjee could come to power in West Bengal was not through repression or anything like that. It was because of the traditional supporters of the CPI(M) abandoned that party. One reason for this debacle is that the CPI(M) in West Bengal started operating like any other traditional party. It had its own base, its own supporters. There was no excitement at all. They were like the others. That is why they lost. Refusing to admit this is not honest at all. I have many friends in the CPI(M) whom I like a lot. But I hope that they will at least try to analyse the defeat properly. Unless you do that, it is difficult for anyone, even the new people, to move forward. A good and honest dissection of what went wrong is very necessary. But it may be too late for that. Overall speaking, because of these reasons, there didn’t happen too many upsets for the system in 2008.

It is curious that it is not only the left-wing politicians who use that “rhetoric” against neoliberalism and globalisation but the right-wing also does that. Trump’s protectionism is a good example of this. We also see that in many countries ordinary people go behind right-wing leaders, taking their “anti-neoliberal economic vision” and “anti-globalisation” rhetoric on trust. But after occupying the office of power, the same right-wing leaders also go in for harsh neoliberal economic policies. How do you explain this?

As I explained earlier, the Left has suffered heavy blows. People felt that the Left has no alternative to offer. People on the Left can argue with one another on why and how the collapse of Soviet Union happened. …Millions of people who live on the globe perceived the collapse of the Soviet Union as the big defeat of socialism. One may not like that analysis. But the general view was that a particular system has failed and it will take a long time to come back from such a heavy defeat. At that time, people came up with theories of the end of history, etc.

The number of people who used to vote for the Left parties or progressive parties or social democratic parties also changed their mind, and they shifted either to being apolitical or in some cases they shifted to the opinion let’s give right-wing parties a chance. And they did it in many parts of the world. India has the largest political victories for the Right. The right-leaning parties in India and in the Arab world, which grew popular, were associated in some shape or form with religion. The explanation is obvious. Yes, there was a vacuum. The Left failed to fill the vacuum, and the Right parties filed the vacuum.

Basically, it was parties of the Right which, as you rightly said, made use of the neoliberal crisis and offered some form of state intervention in many parts of the world. But this came hand in glove with chauvinism, attacks on minorities, targeting minorities and making them the scapegoat for the crisis. The Right did something on the economic front which was a slight shift from neoliberalism. Italy has now got a technocratic, undemocratic government. But prior to that it had a right-wing coalition which included fascists who talked openly against Muslims, refugees, etc. In the U.S., during Trump, it was a big shift to the Right in terms of organisation and then people come to occupy parliament, etc. So it is a global shift. Of course, we have to criticise it. But before doing that, we have to recognise that it is these forces who are in government in many big countries.

In France, we see the Far Right party led by Marine Le Pen mobilising a lot of people who traditionally used to vote for the French Communist party. This is because they find the Right parties convincing. She does talk about the needs of the poor. Also, it is an outcome of refusing to accept the extreme Centre governments which have existed in different parts of the world. It is a break with that. I am saying these things not to demoralise people, but we should have this point of understanding. If you don’t understand that there is big shift towards the Right, then you can’t develop any coherent and feasible Left politics.

Dictionaries characterise “populism” as the “political effort of ordinary people to resist elites”. Many people talk about left-wing and right-wing populism. How do you read populism?

The word populism has been grotesquely misused and made into an abusive word by the neoliberal extreme Centre in many parts of the world. Historically, populism was a word used to define huge movements which were not exclusively or particularly linked to the working class. So when you say there is big popular movement in Argentina during the years of the Perons, it means it was a mass movement including the working class. Petty bourgeoisies were also mobilised for national aims. The neoliberals have effectively used populism as a mark against the intervention of ordinary people in politics. Why were all the South American regimes defined as populist? It is because, in addition to winning electorally, they mobilised a lot of people to do it. In the 20th century, this was a normal thing. Large numbers of people did participate in politics. Now this is not encouraged. So this word has been reinvented to say it is extra parliamentary. In South America, they use it against the Left, and in Europe they use it against Far-Right parties. In my view it is a barren debate. It is a debate being created to make people on the Left confused about what they should do. If by populism you mean mass participation in politics, we support that. That is much healthier than restricting politics to bankers and politicians on their payrolls in parliaments.

European dilemmas

Britain has exited from the E.U. You are a sharp critic of the E.U. People like the Greek economist Yanis Varoufakis took a stand in favour of Britain being in the E.U. According to you, what are the structural issues of the E.U.? What is its future?

The E.U. is effectively not a democratic institution. Varoufakis and I don’t have any disagreement on that. The only question is whether you fight it [from the] inside or the outside. In my opinion, it is the Germans and the French who dominate the E.U. Germany, in particular, makes the decisive decisions. Sometimes, even the French don’t agree with the Germans. The European Parliament is a complete joke. It is just a group of politicians elected on a very low number of votes and paid huge salaries having a good life and time. It has no powers at all. Effectively, the E.U. is run by a giant bureaucracy under the domination of the Germans. Germany is the single most powerful country in the E.U. This was true even when Britain was a member in it. Just because Germany was defeated in two world wars doesn’t mean that it is no longer a big power.

The E.U. cannot be democratised the way it is structured in the present format. It would have been better and possibly more useful if they hadn’t expanded the E.U. but kept its membership to Germany, France and the Benelux countries and developed a social democratic union. That was not likely to happen once the changes of the 1980s and 1990s took place. So we have a sprawling union which is effectively run by the Germans, helped by satellite states like Holland, and at a distance, the U.S. keeps a watch. When Britain was in the E.U., it obviously carried out the U.S.’ instructions. So, its presence was disliked by many countries. With Britain out, the only power the U.S. can rely on inside the E.U. is Germany. I think that soon we will witness a new rise of German militarism. They will want to be part of the so-called international missions in other continents, they will want to sell their weaponry abroad and they will want to be a big power. Of course, this is the logic of capitalism and imperialism.

Yes, there are some good things with the E.U. You don’t need a visa or passport to travel within the E.U. Travel is much easier. But as far as the idea of a federal Europe is concerned, to have a common currency without a federal Europe doesn’t make sense. No one has ever managed in history to get a currency without a centralised state in charge of it to work. It has worked so far and that prevents other countries from leaving the E.U. Britain could leave, of course not easily, because it never get off the pound sterling. The Greeks considered, privately, reviving their currency at the time of their clash with the E.U. They could have done it, but the then government under Alexis Tsipras capitulated completely. The political result of that is the shift towards the Right in Greece. So in terms of a common currency, it becomes very difficult for the smaller countries even to leave the E.U. for contingent and important reasons. Lots of people in these countries are tied to the E.U. currency, the euro. Their pensions and investments are in euros. They don’t want anything that will damage their currency. This is what keeps the E.U. united even after Britain left.

On other terms, you have so-called issues of human rights and similar things, and you have governments in Hungry and Poland which are very right wing in their social attitudes, but there is nothing the E.U. can do about it. The former Yugoslav states are effectively E.U. colonies now. If you look at Herzegovina, Croatia or Slovenia, these are effectively E.U. colonies and do what Germany wants. So this idea of the E.U. as a gold standard was always rubbish and this is proved to be more and more true.

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank have played an important role in international economic affairs since their formation. You are a critic of these two institutions. How do you analyse their?

These two institutions are fairly crucial to the capitalist economic order imposed by the West on the rest of the world. This is one good reason for being critical of both these institutions. Despite all their propaganda and statements, these bodies are effectively there to help the elites and those close to the elites. Sometimes, the World Bank puts money into projects to help the poor. But this is a sort of Oxfam-type help, a little bit there and here. Nothing is done institutionally or structurally by these organisations to enable countries to move forward. In fact, these are the instruments to ensure that the stability of capitalism is maintained by punishing the poor. When they are fighting each other, it entertains me greatly. They are at the moment arguing and fighting because the system is in a bit of mess after COVID-19 and the lockdowns. These are not neutral institutions. They serve the Western world and the U.S. in particular. The U.S. runs the World Bank, and the IMF is shared out with the Europeans. To be frank with you, if we were to have a proper and truly global institution which serves the interest of the poor, then it should not be based in New York. It should be based somewhere in Asia or in Africa.

Immigration has become a burning issue in Europe. Many have explained how a strong anti-immigrations feeling worked in the Brexit vote. How do you look at this issue? The journalist Patrick Cockburn said that Europeans are in a state of denial about their foreign policy outcomes.

It is true that the margins of cheap labour during Britain’s membership in the E.U. created the basis for quite a strong feeling, especially in the northern part of the country, of how they were deprived of their jobs by foreign labourers. This was not exactly the case. Yes, it is true on some levels, but they were deprived of their jobs because they voted Margaret Thatcher to power three times, and she had deindustrialised the country. That is the core of the problem.

The entry of migrants from Poland, Romania and other parts of the Europe was a response to the need for cheap labour, which the capitalists in Britain were prepared to pay. This phenomenon happened for the capitalists as the local people were not ready to work outside the union structure. The hostility to foreign labourers was not totally racial. I mean Polish people are white, if not whiter than the British. But they were the main targets in many cases. And other eastern European migrants and the Romas were also targeted. So that was a different form of hostility towards migration.

Then, you have Islamophobia and hostility to refugees from the Middle East [West Asia]. These migrations are completely linked to the six wars they, the U.S. and allies, have waged since 9/11. The refugees have come as a result of these wars. Look at what is happening in Afghanistan. After 20 years of occupation came to an end, lots of Afghans and also people who collaborated with and worked for the occupation are now refugees. Who can blame these people who now try to migrate to the West? They leave the country because the West destroys the country. Invasion destroyed the social infrastructure and, of course, privileges of small groups. These people and some others want to be refugees. So the problem lies in the wars waged by the Western powers. Angela Merkel’s decision to take a million Syrian refugees was remarkable but also dramatic because it created very rapidly parties of the Far Right in Germany again. Then all the masks came off. The solution is to stop fighting wars and conquering other countries. Where should the people from these invaded countries go other than to try and seek refuge in the countries that wage war on their country? It could be said like this: every time the West is about to wage a war, the people in these countries should be told that the result of this war is going to be at least two or three million refugees. So let us, all the countries waging this war, divide and take the refugees proportionally. If these powers make this announcement, then we will see how far they get people’s support. But they will never say that.

Media as the weapon of the state

How do you analyse the changing media landscape in the world, especially with respect to the dominance of the Western media?

When we talk about the media, television and radio were 20th century media. The 19th century journalism was print journalism where newspapers and magazines dominated the scene. Truly, in capital terms, in order to sell more newspapers, the proprietors of newspapers felt that they had to provide limited information and mimic more obscene versions of television culture. In India, in the 1960s and 1970s, The Times of India used to be a good paper; it had strong journalists. It had critical voices. The same newspaper completely degenerated. It applies to all. One has to understand the processes that led to it. The processes are the overwhelming power of the image. The domination of old classical Western media and its mimics abroad became very powerful in the last two decades of the 20th century.

But especially after 9/11, it began to be challenged more and more by other voices. The overwhelming power of the image produced by the Western channels was challenged by Al Jazeera and, later, by TeleSUR, the television channels set up to create an alternative set of images for the people. The U.S. did not like it. Al Jazeera was under very heavy pressure. And if you add to that, the emergence of the Web and the ability of people to write what they want was another challenge for Western dominance. From the years of “manufacturing consent”, we have moved to the years of manufacturing dissent. Though it has not been as popular and not been as successful as manufacturing consent, at least it exists.

Often, during big crises like wars and uprisings, it’s useless watching BBC or CNN and its equivalents. One immediately goes to websites of magazines of institutions for whom you have a slight respect thinking that it is where you get a better analysis. The point I am trying to make is that manufacturing consent is linked to the needs of the state and also against the forces linked to movements of the opposition who have no power. A right-wing journalist from Daily Mail said that he regarded a report on BBC as completely biased and completely fake. After a long investigation, the BBC said that the journalist’s criticisms were correct and the report as it went was unacceptable. This was their response to a journalist from the Right. Even the right-wing people are embarrassed by the level and the degree to which the BBC had effectively become a propaganda outfit. It is linked, of course, to the changes and shifts that have taken place in the world.

During the years the Soviet Union existed or revolutionary China, the West wanted to show that they were more powerful because they had a free press. So there was much more space for discussion and dissent. With wiping out the enemy, they do not need to do it. So they just either tell lies or publish very few dissenting voices. The classic example of this is the decline that has taken place in The Guardian. The English version of The Guardian has been in a huge decline in standards of reporting, in what is reported and not, and in the op-ed pieces. This one can go through all liberal magazines. This can lead to strange episodes such as President Trump being interviewed on Fox TV by one of his favourite journalists. The guy asked him what he had to say on Putin. Trump gave a non-committal reply. And then the journalist said: “He is a killer.” To which Trump replied: “There are a lot of killers. You think our country is so innocent?” This is something that shocked liberal America. Oh God, he’s equating us with the Russians!

There was a very revealing documentary made by a Canadian documentary maker just at the beginning of the Iraq War. It showed how the media covered the war. And they had footage of Western journalists based in Qatar, not far from where planes were taking off to bomb Iraq, in a large place. When news came on the big screen of bombing and then the information that the Iraqi army had collapsed and Baghdad captured, all these journalists more or less without exception stood up and applauded. The image actually gives you a much better understanding of where the mainstream media is.

The mainstream media often work like the campaign weapon of the state across the globe. Naom Chomsky and Edward Herman talked about how the mainstream media manufacture consent for the status quo. Could you speak about this role of the mainstream media?

I am not surprised that they do that. A South Asian journalist once told me that the British have transformed the control in dissemination of news and how it is presented into an art form. When the German Propaganda Minister during the Third Reich, [Joseph] Goebbels, was asked where he learned this “art” and such things, Goebbels said the British propaganda during the First World War portraying Germans as evil, child eaters and the worst people in the world was very effective. He said we learned a lot from the British. The notion of objective British press, which was an image created by the same press and the British, is now exposed for what it was.

Things have changed on many levels. Not simply news information. I will give you an example. Some of the young people who created the satirical TV programme Monty Python’s Flying Circus for BBC were friends of mine. They said to me that they went to see the head of light entertainment in BBC and said we have this idea for a programme. And said they were going to provide two or three sketches of what they were going to provide. John Cleese, Terry Jones and Michael Palin demonstrated it. The guy kept smiling and said: “I don’t like it actually, but I will give the money to make this film.” That programme became the biggest BBC success. That encouragement of creative dissent is under fire now. All the creativeness which comes with autonomy has gone. This is a universal phenomenon too. All the talk of freedom of press doesn’t make much sense. It makes sense that you can interview me and I can give whatever reply I have. This could not happen if I am living in some other country. But institutionally, manufacturing consent is now manufacturing propaganda for state power.

With the coming of social media, the definition of media changed drastically. All the social media companies are super-rich multinational corporations with an enormous amount of digital data in hand without any limits such as borders, audience and content. So they are big influencers. What are the prospects and challenges?

What one can say is that it is uneven and it is inconsistent. Its potential remains great actually. But the way it is turning now is disappointing. Governments try to constrict it, and the founders of the World Wide Web and those who allow these networks to be on our computers interfere with it in many ways. On Facebook, I have received lot of notifications saying we couldn’t put this up because of Israeli pressure. So censorship in some form is beginning to affect social media. It would have been strange if it didn’t happen. Though social media is global, it operates within frontiers. China, Pakistan or just any other country can switch these things off so they can’t be watched there. Many countries, including the above mentioned, have done this. Its universality is also limited. But, by and large, it is a good thing. It is basically an instrument, and you can use it whichever way you want. All I advise people is that don’t believe everything you read on it even if it satisfies your political or any other instincts. You may still use your intelligence to judge whether the things that appear on it are accurate or not.

New Left Review is the magazine I have been associated with over 50 years now. This year, we have finally decided to launch our blog called Sidecar. We have decided that articles which can’t wait two months to appear in the next issue of New Left Review will be published in Sidecar. This decision had a huge impact in intellectual circles. A layer of young people from different parts of the world have come dramatically to us asking if they can write this or that in our blog. This is because they know the new space. The other impact is that it really revitalised the print magazine. So today we have lots of young people who don’t know New Left Review writing and reading Sidecar.

I would say that there is no one view on the Web. I think the technological revolution that made possible social media, and we should remember that it happened in the U.S. not in Europe or in China, has made a great transformation in communication. The other day, my five-and-half-year-old grandson came to see me, and I was in my study. He looked at the old machine on my desk and asked what is this? I said this is a typewriter. Then he asked what do you do with this? Then I typed his name and said this is how your name would have been written in the old days. He wondered before the computer? Are you kidding me? He couldn’t believe that there was a time when we didn’t have computers. So this technological advancement has created revolution.

The creation of the World Wide Web was a technological revolution in capitalism. In the 1960s and 1970s, the Marxist economist Ernest Mandel had argued that soon we would invent technology where workers occupying one factory in country X could communicate either with workers occupying different factories in the same country or with factory occupations in a third country. He was proved right. So social media’s ability to create its own agenda is something that shouldn’t be undermined as long as you maintain a critical perspective.

You have been with the “New Left Review” for years. Would you make a self-assessment of its contribution?

I am very proud of that magazine and my association with it. We were determined to carry on the magazine in a slightly different way after the defeat in the 1990s. We have maintained our level of critique and debate. We have never accepted the system as something that is positive. We have analysed it on every possible level: political, economic and cultural. We recently created a new blog called Sidecar, which has done two things: brought a new layer of readers from all over the globe and many of them become subscribers of the magazine too. So we have this process of renewal, and two younger editors are in charge of the blog. And we comment on everything under the sun. So it is an alternative not in the sense of saying this is what you must do but in the sense that this is what you should understand. These are the problems that confront us! One reason why we do write on film-makers on the margins in Taiwan, in China, in Iran, the Philippines is because some of the interesting critiques of the world we live in comes from these film-makers. I wish I could say this about India, which had this tradition in the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s. But it is a tradition that is completely gone. Pakistan never had a film tradition. India had a film tradition like the master works in the film tradition of Satyajit Ray in Bengal. These works no longer exist in India.

In the 1960s and 1970s, there were other, similar magazines like New Left Review, but they aren’t now. We have kept this magazine afloat, and this is an institution necessary for the Left. Together, it is attached with a publishing house, The New Left Books/Verso. We have produced, carry on producing and translating important books from all over the world. I am very proud of this achievement because it didn’t happen automatically nor did happen without tension, debates and splits. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, there was a big split in New Left Review. Those who were in the editorial board who didn’t like what we write about imperialism or about the civil wars in Yugoslavia left after a big fight. But we kept the magazine. There are these new young intellectuals who carry the magazine. I am confident that both the magazine and publishing house will see out this century quite easily. We will be dead and gone, but they are there.

Digital surveillance & democracy

The scope of digital surveillance is enormous in the present world, and it is widely used across countries. How threatening is digital surveillance to democracy?

When technology advances, every form of it advances. You can’t say that it would have been better if you didn’t have these technologies. That is an untenable view. But the surveillance is of course happening on a grand scale. Every citizen can be under the surveillance. Recently, it was admitted by the police in an official commission of inquiry that they had been carrying out surveillance of me for the last 45 years. Governments have carried out surveillance for long years in history. The German secret police, during the Nazi era, used to be held responsible for large levels of surveillance. What they did was nothing compared with what the wise people are doing today. Think about Edward Snowden. Nice, young, American, white conservative boy gets so upset working for the national security people! That level of surveillance is difficult to digest.

Democracy is becoming largely a burnt-out shell in different parts of the world. Did we have the perfect democracy before digital surveillance? The answer is No. Different ways and means of spying on people were used before digital surveillance. Infiltrating groups, spying on them were all done by the status quo with all the progressive movements. The scale of this is horrendous now. Anyway, democracy itself has become very limited. It is still true that anyone can stand for elections, but the state makes sure that there are only two or three key players in each country. As I wrote in the book The Extreme Centre, whether you are Right Centre or Left Centre, you basically do the same sort of things. You go behind capital and its interests. This democracy is becoming more and more shattered and broken in the countries where it first emerged. Many billionaires often say that the Chinese economic system is a good system, and they don’t need to bother about this or that aspect of the political system there. But all these raise serious questions.

You have observed that with the collapse of the Soviet Union, the ideology of social democracy also collapsed. According to you, what was the influence of the Soviet Union in keeping social democracy and the social democratic ideology in place?

As long as the Soviet Union existed and as long as it was seen as a serious threat to the West—in my opinion it was never a serious threat—the capitalist world had to depend on social democracy a great deal. The USSR and the socialist countries kept a socialist social structure. In the West, it was effectively a social democratic consensus that kept going till the 1980s. Once the USSR imploded, there was no need for that. They could just revert to capitalism. What is known as neoliberal capitalism is a reversal to the conditions that existed on many levels in a very different technological time of capitalism. A new age came into being, with new millionaires and billionaires totally dominating the scene. China and the former USSR, which had been outside the grip of capital, are now part and parcel of the system. So it was a huge triumph for capitalism. For the first time ever, they began to refer to capitalism as capitalism, and they no longer need to use the words like freedom and democracy to self-describe. It is capitalism now. I often think that it was the USSR which kept the West democratic. With the disappearance of the USSR, democracy doesn’t matter. Democracy is largely a set of rituals now. It is completely hollowed out. The symbiosis between big money and politics is now noticeable. So the collapse of the USSR has not necessarily been helpful to capitalism in the medium term and it will not be in the long term also. That is what was reflected in the Wall Street crash in 2008 and in the COVID-19 pandemic.

What about the changing faces of capitalism?

Of course, capitalism has changed. The whole point about capitalism about which Karl Marx was very clear when he wrote that it is a system that is continuously evolving and it remains an exploitative system essentially. It remains a system in which profit and wealth are the essential determinants of who rules. The technological revolution spearheaded by the U.S. created the Internet, and we now live in that world. Financial capital is well ahead in the Western world of industrial capitalism, which is what the previous capitalism was based on. The two variants of capital are same on some levels, but it is very different in functioning.

The nature of revolutions in Russia & China

You made the following important observation on former socialist societies: “People do not want to return to that system for obvious reasons. Economically, it was austere and backward where it happened. The total outputs of those societies were constrained by scarcity. There was low productivity of labour. Politically, most of those countries were dominated by authoritarian state apparatus which took away civic liberty.” What could have been done to avoid what you observed?

The problems were structural. Two important socialist revolutions of the 20th century happened in the largest countries of the world, namely Russia and China, where the working class was a relatively small minority. So, from the beginning the Russian and Chinese revolutions were involved with this problem. Certainly, in the Russian Revolution, Bolsheviks had a majority of the working-class support and that is how they won. And gradually they began to get poor peasant’s support. But the voluntaristic way in which they approached the question of industrialisation isolated the regime from the bulk of its people. This created problems on the political level too. I have always made this argument that had Lenin lived another five years, the political structure of the Soviet Union might be greatly different. This is because towards his last years Lenin was very angry with many of the things taking place and especially the power and strength of the old tsarist bureaucracy within the new system. Bureaucracy was basically operating in the same old way. One reason for that was that the Bolshevik cadres couldn’t replace them.

Another issue was that the country itself was underdeveloped. The civil war, which could have ended very quickly had the West not intervened to help restore tsarism, took over the lives of some of the most advanced working-class militants in that country. So the new layers of people who were transported from being peasants into being workers came from a different level of political consciousness. So there were lots of problems. But the other side of the Russian Revolution which was also receded was that the revolution was not simply the party. It was the combination of the party and the Soviets. The Soviets were for a long time elected bodies. They were elected bodies where other parties had a majority, including the Conservative cadets, the Mensheviks, smaller peasant parties, etc. It was only when they fought for the majority and won the majority that the Bolsheviks discovered that it reflected the majority of the working class. When they won this majority, they decided to make a revolution. That didn’t alter or detract from the fact that Russia was a backward country. Marx and the Communist Manifesto was proved wrong by the Russian Revolution and the Chinese revolution. The revolution came not in advanced countries where the working class was most advanced but came where the working class was relatively a politically backward social class. This had created problem with the political structures too.

The one-party state [that was] meant to be a temporary solution during the civil war became hardened into an institutional solution. This ultimately led to the domination by the Politburo and one leader. This was also the model taken up by the Chinese in different circumstances. Whereas the Russians moved from towns to the countryside and worked through industrialisation, the Chinese revolution was forced to move to the countryside by the Japanese invasion and also by the viciousness of the Kuomintang, the bourgeois nationalist party whose main enemy was communism rather than the Japanese. So, the bulk of its years fighting and resisting the Japanese occupation and later the Kuomintang came as they were in the transition of moving from the countryside and taking the cities. That gave them a link with the peasantry that the Russians never had. By and large Mao [Zedong] and other leaders were careful of how they dealt with the countryside. They didn’t push with any craziness.

The political structure in both Russia and China was the same: single party, Politburo control, single leader. This model was taken over and imposed in different parts of the world. Many colonies in the Third World seeking freedom from the imperial powers adopted a political structure and model which they thought was progressive because these revolutions were progressive. They linked both automatically. There were problems with the economic model too. There is no question that economies would have benefited had there been an intermediary between the command structures and the needs of the economy. Yes, it is true that in some form of Soviets criticism could be made and discussions could take place. But that was not the case everywhere.

So this political structure was disastrous for the Eastern Europeans in addition to the Soviet Union. Because they came from different traditions. What happened in these countries was the strict imposition of the Russian model, which after the death of [Joseph] Stalin and relaxation became less oppressive. I would characterise these countries in Eastern Europe as social dictatorships and authoritarian political model.

But mega reforms of structures, and social transformation by the abolition of capital, state backing of health, education, etc., are what people miss today in these countries. That is where this nostalgia lies. People think that in the old days things might have been bad, but they were able to pay house rents, and they had subsidised electricity bills, etc. I was in the Czech Republic several years ago. A young student doing PhD said she was denied her PhD by her professor because she had not quoted Henry Kissinger. So sometimes, the allies change, but the system of thought remains same. That is why many think socialism is failed forever. But my reply to that is socialism failed once unlike capitalism[, which has failed] many times.

There is no socialist blueprint. If you think there is a socialist blueprint, then you will only be a utopian. The formation of economic policies has to be done with the collaboration of those on whose behalf you are going to change structures. And in that the traditional communists never succeeded. That is where the large part of the problem lies. Even in the Soviet Union, there was no huge mass mobilisation demanding that the Soviet state system be dismantled. Alas, this dismantling was done by the people on top who were not visionary, had run out of ideas and didn’t know what to do.

Latin American experience

You are a strong supporter of the progressive Left movements in Latin America. How do you look at today’s Latin American politics and people’s movements?

I have extensively written about this in various places, including in the book Pirates of the Caribbean: Axis of Hope. The Latin American development is uneven. I never characterise it as 21st century socialism. My own characterisation of it is left social democracy based on mass movements. None of them ever came close to or wanted any break with capitalism. They said themselves that this is not their aim because it is very difficult to pull that off these days. These were elected governments encouraging the participation of ordinary people in daily life and setting up some structural changes on various levels. The targeting of Venezuela by the U.S. and the Western Europeans was quite devastating in its impact. Venezuela was the sort of mother of all developments that took place. What they never achieved, though they were trying, was some sort of stable economic bases to keep going. The attempts by the U.S. to topple the Venezuelan regime has failed so far. Juan Guaido is promoted and recognised as the President of Venezuela by the U.S. and by some European countries. The Bank of England confiscated Venezuela’s gold reserve. Venezuelans were stopped from travelling. It is non-stop harassment of this country. But still they have not been able to topple [President] Nicolas Maduro. One reason they have not been able to topple Maduro is he has some mass support. The second reason is that the U.S. thought that they would be able to buy off the army generals but they failed to do so. Actually, one of the generals came out and said we feel deeply insulted that the United States did not realise that we are Venezuelans and they thought that they could just offer us money to topple and change our governments. So this particular crisis goes on.

In Bolivia, they succeeded in toppling Evo Morales but not for too long. They had to commit to an election and the party of Morales won that election with a very good candidate. Morales came back to the country from the exile to huge applause. In Brazil, we saw a successful constitutional coup. We have seen an attempt to completely eliminate [Luiz Inacio] Lula da Silva from the political scene. The court had to release Lula. There was no evidence they could buy. It was an attempt to prevent him from contesting the election against [Jair] Bolsonaro. To call Bolsonaro a fascist, which many people do, is abusive. There are elements of him which are in that direction. The real problem with him is that apart from his extreme right-wing views, he is mentally unbalanced. So he speaks crazy things about every subject under the sun. Compared with him, Donald Trump was the voice of reason. All the opinion polls are showing that if there is an election now, Lula would win easily. We shall see that at the moment the situation is quite hopeful and there are younger leaders emerging in the country, like the leader of national homeless workers. It’s been a very popular movement. When I went to Brazil last time, in Sao Paulo I went to see some of the camps which had been created for homeless workers and met their leaders. Guilherme Boulos [leader of the homeless workers] is extremely popular. Lula himself has spoken in big rallies organised by Boulos. I often compare Brazil with India. Here too Brazilians are ahead. They are producing new leaders. Indian socialists and leftists should follow the Brazilian developments closely just in terms of structure and organisation.

As far as other South American countries are concerned, Argentina is always up and down. Chile had a referendum recently to rewrite the dictatorship-era constitution. This is the first concrete attempt to structurally challenge and change Augusto Pinochet’s dictatorship measures. It is mass movements from below which came and put pressure on both conservatives and so-called socialist parties to act in this direction. Victory in Chile is not unimportant.

To conclude, I would say that what we are witnessing is not a situation where the Latin American progressives have been defeated. They have lost, but they are coming back. It’s an uneven and uneasy situation where it would be wrong to write them off completely. The U.S. has not been able to re-establish the dominance and control which it had in 1950s, 1960s and 1970s.

Challenges before China

You say that “China is the workshop of the world”. Where do you place China in the present geopolitical landscape?

This is a billion-dollar question. It is mainly about how China develops, what happens internally and how China is treated by the U.S. and allies. Despite and because of the amazing success of China’s national capitalism, they have to go about and create a proper social welfare state in which health and medicine, which used to be free, have to be actually improved. You do have financial inequality in terms of salaries and this is huge. Wage differences and salary differences in China are now above those in the U.S. Huge social inequality is there in China. It has to be stopped and changed now, and if the government fails to do something for the bulk of the people, then there will be social upheavals sooner or later. The Chinese government is very nervous about it. They should be scared because China has a very long history, stretching back to 2,000 years, of rebellions: 20th century rebellion of peasants, the working class and students are some modern examples of this revolutionary militancy. When people feel that something needs to be changed, they march for this. It happened in Tiananmen Square as well in 1989. These are the examples that they have to look at if they want to stay in power.

In terms of the U.S. attempt to contain and push back Chinese economic dominance in large parts of the world, they are playing with the fire. The new nuclear pact signed with the Britain and Australia, the AUKUS Pact initiative, is designed to have nuclear submarines constantly keeping watch on China underneath the China Sea and the Pacific. It’s a provocation. I think it’s a provocation designed to force China to spend more and more money on its arms programme. That is the aim of this exercise.

There is an interesting book by the scholar Isabella M. Weber explaining how China survived the shock therapy. She says that it happened because the Chinese state kept its control over developments. They were very tempted at one stage to go on the shock therapy route. They even started, but they pulled back in time. And that pulling back was extremely important for understanding the spread of wealth and the emergence of new cities and social infrastructure.

The other possibility for the U.S., which is dangerous, foolish and destructive for everyone, is to try and use the unrest in Xinjiang to try and stabilise China from within. It is one thing to criticise them for the some of the mistakes they have made in dealing with their own ethnic minorities in Tibet and Xinjiang. We can do that. But if the West tries to provoke uprisings in Xinjiang, China will respond. I don’t have any idea of how will it respond. What makes me nervous, as I said earlier, is that there are tens of thousands of Uyghur refugees in Turkey. Many of them have been trained in live wars, including in Syria, on how to fight, on how to blow up things, etc. If the plan is to send them to China, it will not help people in Xinjiang at all. The result will be that the Chinese will get tougher and pack people from other parts of the country into the region. That is what they have done in the past. That is what they might do now. I hope they will not do it. I stress this repeatedly. They should not do that.