Amid the wreckage of wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, the United States and its allies have turned their sights on China. University of Victoria professor emeritus and historian John Price examines the rise of the coalition of Anglo settler colonial states of Canada, the United Kingdom, the U.S., Australia, and New Zealand, and how they are today fomenting conflict in the Asia Pacific. You can read the series in its entirety here.

The CBC, this country’s national broadcaster, reported in the fall of 2021 that Canada sent the Canadian patrol frigate HMCS Winnipeg as its contribution to a massive, U.S.-led naval exercise, “Pacific Crown,” off Okinawa, Japan to send a stark warning to China. It followed up this report with another, recounting how the Canadian commander endeared himself to his counterpart aboard the British aircraft carrier HMS Queen Elizabeth, who had paid a courtesy visit to the Canadian ship during the exercise. After sipping Earl Grey tea and munching on English scones with cream and jam, the British commander bemoaned that his officers’ deck had run out of Earl Grey. Provided with “probably a thousand tea bags” by the commander of HMCS Winnipeg, he returned to his aircraft carrier a hero, lavishing praise on the Canadian cousins.

Replete with echoes of Anglo kinship, such banal reporting masks how Canada, through its Pacific squadron, is directly engaged in gunboat diplomacy that, for many people in China, smacks of the same intimidation that preceded the Opium Wars. This recent sabre-rattling, however, arises out of an embedded military network known as the “San Francisco” system. Constructed in the aftermath of the Second World War, the network of bilateral alliance was designed to thwart decolonization and assure the Pacific would become an “American Lake.” To this day, the U.S. maintains hundreds of military installations and tens of thousands of troops in the region, mainly aimed at China.

The San Francisco system

In 2009, Edward Snowden was stationed at the Yokota Air Base near Tokyo, spying on China when he began to suspect the worst about the U.S. spy network and the Five Eyes. His presence in Japan was not by accident, nor was it a result of a freely agreed upon alliance between the U.S. and Japanese governments. The end of the Pacific War in 1945 saw the United States, with the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and others abuse their positions as victors in the war to support conservative forces in Japan, and elsewhere, to resist radical decolonization that was occurring in China, India, Vietnam, Malaysia, Burma, the Philippines and elsewhere.

To resurrect capitalism regionally, and assure Anglo-American hegemony, the U.S. reinforced its military presence, provoking wars, coups, and regime changes in a host of countries. Japanese American historian Akira Iriye and others described this military-economic system that arose the “San Francisco system,” named after the city where the peace treaty with Japan was signed in 1951. Except it wasn’t a peace treaty, but a wholesale system of U.S. military intervention in the Asia Pacific that continues to this day. The U.S. is much more than an “informal” empire.

The system included, according to Iriye, “[t]he rearmament of Japan, continued presence of American forces in Japan, their military alliance, and the retention by the United States of Okinawa and the Bonin Islands. In return the United States would remove all restrictions on Japan’s economic affairs and renounce the right to demand reparations and war indemnities. Here was a program for turning Japan from a conquered and occupied country into a military ally, frankly aimed at responding to the rising power of the Soviet Union and China in the Asia-Pacific region.”1 And there was more.

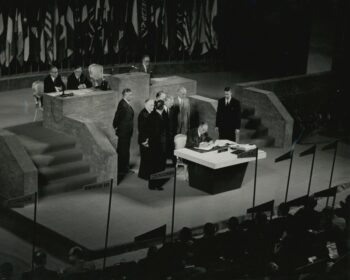

Otherwise known as the Treaty of Peace with Japan, The Treaty of San Francisco was signed on September 8, 1951 by 48 allied nations, officially ending the Second World War and reestablishing Japanese sovereignty. Signed at the War Memorial Opera House in San Francisco, the treaty went into effect on April 28, 1952. Photo courtesy the Council on East Asian Studies at Yale University.

“In the end the San Francisco agreement was only peripherally a peace treaty—it was a series of bi- and multi-lateral military pacts that ensured the Pacific would become an American lake, an ambition that dates from the early 20th century. The U.S. would retain over 200,000 troops in Japan alone, not to mention thousands more in Okinawa, South Korea, the Philippines, Taiwan and, as the decade continued, in Vietnam as well.” This was my conclusion in a paper published twenty years ago as part of the Japan Policy Research Institute Working Paper Series, sponsored by senior American scholar Chalmers Johnson who was as surprised as I was by the findings.2 The U.S. had used its power to manipulate the peace treaty process to reinforce its economic and military hegemony, marginalizing the people and countries that suffered the most from Japan’s imperial war:

Both mainland and Taiwanese China were not even invited to the peace conference. Neither were the Koreas, north and south. India refused to participate in what it regarded as a rigged affair; so did Burma. Three signatories from Asia (Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos) were actually representatives of the French colonial regime and must be excluded from any bona fide count of Asian countries endorsing the treaty. That leaves only four—the Philippines, Indonesia, Ceylon, and Pakistan. Of these four, Indonesia signed the treaty but never ratified it and signed a separate peace treaty with Japan in 1958. The Philippines, although closely allied with the U.S., reserved its signature, and did not ratify the treaty until after it had gone into effect. In other words, the only Asian countries that supported the SFPT were Pakistan and Ceylon, both recent colonies of Britain and neither of which had signed the Allied Declaration of 1942.3

Of note was why the Indian government, with Jawaharlal Nehru as prime minister, refused to participate in the San Francisco meetings, and the response this elicited from Harry Truman, the U.S. president at the time. India considered that (1) the provisions giving the U.S. control of Okinawa and the adjacent Bonin Islands (also known as the Ogasawaras) were not justifiable; (2) the military provisions of the treaty (and the security treaty to be signed with it should only be concluded after Japan became fully independent; (3) Formosa (Taiwan) should be returned to China at once; and (4) objected to the fact that the deliberations to be held in San Francisco would not allow for the negotiation of the peace treaty.

India’s position provoked Truman to scribble in the margins of the Indian note: “Evidently the ‘Govt’ of India has consulted Uncle Joe and Mousie Dung of China!”4 Disparaging India’s government by putting it in quotation marks and referring to Mao Zedong as ‘mouse dung’ while Joseph Stalin was ‘Uncle Joe’ revealed Truman’s deeply embedded prejudices towards people of colour. The peace treaty—a project steeped in racist exclusions—reflected the continuing assertion of white supremacy in the region.

Despite admonitions from staff regarding the problematic treaty, the Canadian Minister of Foreign Affairs, Lester Pearson, threw his full support behind the U.S. strategy in Asia as it played out in San Francisco. This support was essential in 1951. With most Asian countries boycotting or abstaining from the talks, the allied “middle powers” of the UK, Canada, New Zealand, and Australia were instrumental in providing a veneer of legitimacy to what happened. What I later came to realize was that referring to Canada as one of the “middle powers” that abetted the U.S. in passing the San Francisco peace treaty was a mistake.5 At work in San Francisco were not “middle powers” but the Anglo alliance of settler colonial states.

The San Francisco system left much of the Pacific under the domination of the U.S. and its allies, into which it also integrated a beholden Japan. Nevertheless, decolonization movements continued, with U.S. intervention resulting in major wars in Korea and Indochina, with the loss of millions of lives. U.S. covert operations prompted coups in Thailand, the Philippines and Indonesia, with terrible consequences. The scale of carnage makes a mockery of the term “Cold War” in Asia.

U.S. officials perceived the Pacific as an “American Lake,” an economic as well as a strategic sphere of influence that came to include South Korea and Taiwan. The system allowed Japan to rise again economically, while its knock-on effects led to the integration of South Korea and Southeast Asian nations into a dynamic region of liberal capital development. The region, however, arose on the foundation of the San Francisco system, an interlocking network of military treaties and agreements that provides the U.S. empire with hundreds of military bases or facilities in the Asia Pacific to this day.6 This system has caused severe human and ecological degradation in the Pacific, including the sexual exploitation and abuse associated with U.S. military bases (“man-camps”).7

Recent developments in China-U.S. relations must be understood in the context of this San Francisco system. China’s rapid economic has been based on that country’s ongoing support of the World Trade Organization and open sea lanes. In that regard, the U.S. “Pivot to Asia” and its recent meddling in territorial disputes have evoked incredulity on the part of the PRC, and a determination to push back under Xi Jinping. One might disagree with China’s construction of the sea-bases on the Spratly Islands in the South China Sea, or its military maneuvers near Taiwan, but they contain a logic directly responding to increasing Anglo alliance intervention in the region.

Those who demonize China portray it as a global military threat, but this too must be taken with a grain of salt. An appraisal provided by Pulitzer-prize winning historian John Dower a decade ago still holds:

Given the enormous domestic challenges China will face for many decades to come, the goal of its military transformation is not to achieve strategic parity with the United States. That is not feasible. Rather, the primary objective is to create armed forces capable of blunting or deterring America’s projection of power into China’s offshore waters—to develop, that is, a military strong enough to dispel what Henry Kissinger has called China’s “nightmare of military encirclement…the area of particular strategic concern lies within what Chinese (and others) refer to as the ‘first island chain’ or ‘inner island chain’ which includes the Yellow Sea, East China Sea, and South China Sea. Central to this area-denial strategy is developing “asymmetric capabilities” that will enable Chinese forces to offset America’s ability to intervene militarily should, for example, a conflict over Taiwan arise.8

This is a nightmare scenario that could easily escalate, with devastating effects on peoples in the region. Current anti-China campaigns, and the associated notion that we are seeing a “new Cold War,” are sowing the illusion that the confrontations might end as they did in Europe, with the collapse of U.S. enemies. Whatever criticism it merits, China is not the Soviet Union. Emerging as part of the global decolonization process after the Pacific War is a point of pride for many people in the PRC. This and its recent economic successes have resulted in the Chinese Communist Party retaining substantial support from the population at large.9 Continual U.S.-led intervention in the area inflames Chinese nationalism, increases the danger of war, and makes social change difficult.

The Ronald Reagan Carrier Strike Group and units from the Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force and Australian Defense Force participate in trilateral exercises in the Philippine Sea on July 21, 2020. Photo courtesy US Naval Forces Japan.

Just recently, Australia and Japan signed a new military agreement, the Reciprocal Access Agreement, reinforcing relations between the two countries’ military forces. Add this to AUKUS and the Quad and we are witnessing growing belligerence on the part of the Anglo alliance in Asia that began, not with China’s expansion, but with the U.S. “Pivot to Asia” in 2010.

We seem to have arrived at an important juncture in Canada: build on the growing recognition of our settler colonial past, step back from the Anglo alliance machinations in Asia or become further enmeshed in U.S.-led aggression in the region. Such a stark choice demands a reassessment of Canadian foreign policy in light of the long history of racism and settler colonialism in this country.

The Canadian government can avoid stepping off the precipice by distancing itself from the American agenda in the Asia Pacific, and by reining in CSIS. To do otherwise is to reinforce a U.S. empire that was, and is, based on genocide, slavery, white supremacy, and imperialism. Such a project does not entail succumbing to the pressures of the PRC; indeed, it demands that we apply a critical lens to China and elsewhere, without the shackles of racism and liberal presumptions at the core of the Anglo alliance.

Part 6: The China challenge

John Price is professor emeritus at the University of Victoria, author of Orienting Canada, and a member of the Advisory Board of the newly formed Canada-China Focus, a project of the Canadian Foreign Policy Institute and the Centre for Global Studies (University of Victoria).

Notes:

- ↩ Akira Iriye, The Cold War in Asia: A Historical Introduction (New York: Prentice-Hall, 1974), 182. A more recent appreciation is Kimie Hara, ed., The San Francisco System and Its Legacies (New York: Routledge, 2015).

- ↩ John Price, “A Just Peace? The 1951 San Francisco Peace Treaty in Historical Perspective,” JPRI Working Paper No. 78 (June 2001). I draw on this paper liberally in the analysis that follows.

- ↩ Price, “A Just Peace?,” 9. The peace conference aimed to bring together the allies who were defined as those that had signed the Allied Declaration [of war] of 1942.

- ↩ U.S. Government, Foreign Relations of the United States, Vol. VI, Part 1 (1951), 1288-1290.

- ↩ By 2013 I began to rectify this mistake, see John Price, “Canada, White Supremacy, and the Twinning of Empires,” International Journal 68.4 (2013), 628-638.

- ↩ For details re U.S. projections around China see the databased constructed by David Vine, “Lists of U.S. Military Bases Abroad, 1776-2021,” American University Digital Research Archive, 2021.

- ↩ Jon Mitchell, Poisoning the Pacific: The U.S. Military’s Secret Dumping of Plutonium, Chemical Weapons, and Agent Orange (London: Rowman and Littlefield, 2020).

- ↩ John Dower, “The San Francisco System: Past, Present, Future in United States-Japan-China Relations, in Hara, The San Francisco System and Its Legacies, 237.

- ↩ Edward Cunningham, Tony Saich, and Jessie Turiel, “Understanding CCP Resilience: Surveying Chinese Public Opinion Through Time,” Ash Center for Democratic Governance and Innovation, 2020.