In 1947, thousands of youth brigade volunteers from around the world joined their Yugoslav comrades in the hills of Bosnia to build a railroad. As the most popular song from the construction sites put it, not only were these activists making a railroad, but the railroad made them.

Rebuilding Yugoslavia after World War II was a complex task: if five-year plans set lofty industrialization targets, their goals would have been hard to meet even if pre-war infrastructure had magically been restored. The new state also inherited a situation in which the parts of the country with the natural resources and strategic positioning granting most potential for development had been continually overlooked by past regimes.

The central republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina was one such part of the country. While soon earmarked to become the center of socialist Yugoslavia’s mining, metal and defense industries, it had no railway infrastructure to support the industrial boom. Miles of railways had to be laid, and the priority for the limited mechanization and trained personnel available had to be put on rebuilding the existing network, so heavily damaged during the war.

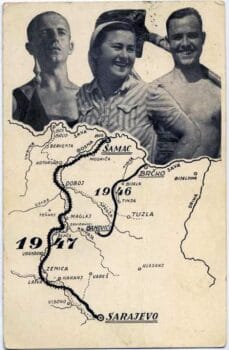

A poster commemorating construction of the Šamac-Sarajevo railway. By Unknown author – Datoteka:Pruga Samac-Sarajevo.jpg in serbischsprachiger Wikipedia, Public Domain, Link.

The new government considered postponing plans to build railroads in Bosnia: passion and good intentions wouldn’t be enough. It was the leadership of the People’s Youth of Yugoslavia who resisted this decision, suggesting that young people–those who fought in the Partisans and those coming of age in peacetime–could build it. This would be an experiment in self-organization: the construction project would have a limited team of professionals doing the specialized work, but most of the workers would be young men and women with no prior experience or training, organized in loose hierarchies. While in name and spirit these brigades would live-action-roleplay the Yugoslav partisans, there would be no strict military discipline or micromanagement of these thousands of youngsters.

Could it work? The government gave them a test: a 50 mile stretch of railway from the coal mining town of Banovići to the important communication hub in Brčko. 60,000 young people from all around Yugoslavia reached the construction sites and finished the railway in six months: the country was impressed and proud. It allowed the leadership set a new goal and be bold: 150 miles of railway going through the rough terrain of central Bosnia, mountains and river canyons, connecting its capital Sarajevo, with the northern town of Šamac, via major industrial and mining towns in the valley of river Bosna. Again, the timeframe would be six months.

News of the success of the Brčko-Banovići railway spread far and wide, and the optimistic target of the new project inspired hundreds of thousands to sign up. It became a competition, a chance to repeat and surpass a previous success, and be a part of this unprecedented effort. This desire to work, create, and build themselves into the foundations of the new state was one of the reasons for young men and women of Yugoslavia (25 percent of the Šamac-Sarajevo volunteers were women) to join the youth work brigades.

Hundreds of thousands of volunteers would exceed by far the mechanization available to support them (in the end the ratio was 9:1), but that would not to be a limiting factor: the railway was never just about work.

There were plenty of other, complementing reasons: it was an opportunity to travel, meet new people, learn new skills, and, for some, to escape the family home. It was also a chance to be a part of brigades continuing the tradition of the fearless Partisans, fighters who fought and won the new socialist country. Their efforts would be recognized with the title of udarnik (shock worker), medals and trophies, mention in the workers’ newspaper. And then also come the afterhours: in the spirit of “three eights” (eight hours’ labor, eight hours’ recreation, eight hours’ rest), significant attention was given to culture, sport, and education–the cultural upbringing of the new generation. Between ten and twenty percent of the 220,000 volunteers were illiterate, and they learned one or two of the official Yugoslav scripts in the courses during that summer of 1947. Students of engineering, construction, mining, had a chance to join specialized brigades and use their existing professional skills, while learning new ones in practice. By the campfire in the evening, the volunteers would sing, dance, and meet their comrades from all around Yugoslavia.

And not only Yugoslavia: the camps along the new railway were the temporary home to 5,842 young men and women from all over the world, gathered in 56 international brigades. Some countries didn’t allow their volunteers to join the action in an organized fashion, notably USA and USSR. Some U.S. volunteers did manage to reach Yugoslavia, and they would join brigades from other countries, as would volunteers from other less represented territories. Notably, the Palestinian group was made out of Jewish and Arab volunteers alike. Politically, the international brigades were a mixed bag as well: from Czech national-socialists (not affiliated with their German namesakes) and Dutch Catholic Youth to British communists, Labour Party members and even conservatives, they all came to Yugoslavia with a vision of a new future of Europe. These visions were reiterated in messages of solidarity and reports of good work done in Yugoslavia sent by the brigades to the 1st World Festival of Youth and Students in Prague—and the effect was immediate. Once the delegates heard the words from the international workers at the railway, they decided to waste no time: two brigades made out of the young delegates went to Bosnia directly from the congress.

Omladinske radne akcije (Youth labour actions) such as the Šamac-Sarajevo railway construction were a major element of upbringing new generations in Yugoslavia—and that is how I perceived them, as a powerful, yet local mechanism with exclusively local effects, significant for Yugoslavs alone. A book that offered me a new, internationalist, potentially utopian perspective on it was the recent reprint (Rab Rab Press, Helsinki, 2020) of The Railway: An Adventure in Construction, a small volume “prepared by British Volunteers on The Youth Railway Šamac-Sarajevo, 1947“ edited by Edward P. Thompson. It is a collection of essays by the members of the British Brigade: some, like E. P. Thompson who went on to pen The Making of the English Working Class, would become celebrated intellectuals, some would become Thatcherites (Alfred Sherman) or Soviet spies (John Stonehouse). Some came to Yugoslavia from classrooms, some from the British army, and some had a Spanish internationalist experience under their belt—and enjoyed being once again in an International Brigade.

While the book primarily tells the tale of their stay in Yugoslavia to feed the curiosity of the general public and introduce a young country thousand miles away, there is another mission it takes upon. The western media coverage of the railroad building campaign was not favorable: the local youth was claimed to be forced to work on the railroad, while the foreigners were claimed to be brought to Yugoslavia with much more sinister intentions. According to the Daily Telegraph, the international brigades trained in the forests of Bosnia were being prepared for deployment in Greece, where General Markos was leading a partisan struggle.

The British Volunteers write a lot, in fact, about the Greek volunteers who were stationed right next to the British in the village of Nemila. The Greek brigade consisted of Greek refugees who had come to Yugoslavia in 1945 and who were allowed to stay, provided they did not interfere with the civil war in their homeland. While building the railroad, the British and the Greeks competed at work, in sports, in arts and music; and this, soon after the British Army had been at loggerheads with the Greek partisans. The secretary of the Greek brigade had been wounded by British soldiers in his homeland, and all the members of the brigade wanted the British forces to leave Greece: they were vocal about it, and some British Brigade members would join in the Greek chants of “Brits out” wholeheartedly, and enjoy the loud “Harry Pollitt–Zahariades” as a response to “Tito–Stalin–Dimitrov” chants from other brigades. It took the British some time to get used to chants as means of expression, but the culture shock was resolved quickly in the intense pace of the work, recreation, and exchange of experiences, hopes and dreams of a new, post-war generation.

The essays paint a vivid picture of work at the railway—even though the British Brigade, and some other international brigades couldn’t reach the status of shock workers (750 international volunteers made it), they did their best and participated in every activity in that part of the river Bosna valley. Another vivid image is that of the camp fires, music and dancing; here the British volunteers never ceased to be amazed by the Greeks, the Albanians, the Yugoslav: next time, they say in their essays, we would have to prepare something representative of our culture.

The authors of the essays in Railway do not hide their delight at the tour of the Yugoslav seaside the government organized for the international brigaders; neither do they hide the revolutionist against the treatment Palestinian volunteers faced upon return to Palestine, or the fascist attacks on European volunteers while transiting through Trieste on their way home. They enthusiastically list the improvements the international and local brigades could make next time they go to Yugoslavia, next year–they hope. However, 1948 brought the Cominform resolution in which the pro-Stalin Communist Parties condemned Tito, and Yugoslavia was effectively blacklisted. Even in this state of blockade, some international brigades still found their way to Yugoslavia, to the construction sites of the Brotherhood and Unity Highway.

While Thompson’s account is detailed, he himself recognizes that he has “failed to give flesh and blood to the story. Perhaps this can never be done unless one goes to see and work oneself”. The emphasis there is Thompson’s, and it resonates with his understanding of Yugoslav strategy: the Yugoslavs did not regard the Railway as one more friendship jamboree. If the World Youth Festival was the drawing-office of international unity, then they intended the Railway to be the foundry. They realised that travail symbolique leads only to amitié symbolique and they had a far profounder aim in view. They believed that hard work would lead to hard-headed understanding.

It is hard not to draw parallels with the reconstruction of Yugoslavia after World War II, and the reconstruction of Yugoslav republics after the wars of the 1990s. A literal parallel is the plan to build a highway through Bosnia, next to the route of the Šamac-Sarajevo railway. Extrapolating from the current progress of this construction project, which is repeatedly hailed as the most important infrastructural endeavor of the country after the war, its completion could be expected in two decades.

The actions that started with the Šamac-Sarajevo railway continued until early 1990s, throughout the existence of socialist Yugoslav state; many a veteran of such actions would rather the railway today could similarly mobilize the enthusiastic youth. Once left to the “invisible hand” to build it, the highway remained invisible. A volunteer arriving to Bosnia after the 90s war, arriving either through a humanitarian or a missionary organization, would not be steered into a large infrastructural endeavour: it wasn’t aligned with the strategy of the organisations, nor stimulated by the local authorities. In such a setting, most of these efforts were bound to become the inevitable travail symbolique. International aid in post-war Balkans disappeared through the cracks: material aid eaten by corruption, work by volunteers uncoordinated and often misguided by a combination of political and religious motives failed to make a substantial difference, and so did the inevitable travail symbolique.