Freedom is a habit and for Africans throughout history, it is one that can cost you dearly while under the repressive state apparatus of an imperialist power. Despite this, it has rarely discouraged those who’ve taken up the program for Black liberation from making the ultimate sacrifice out of their love for the people. Recognizing the colonial status of Africans in the U.S. and in the diaspora is only the first step. Through organization, struggle, uniting around a set of principles and an unwavering commitment to the movement is where some of the strongest and most fierce of the litter emerges: the Panther, on the prowl, unchained, forged through fire, a deadly weapon of theory.

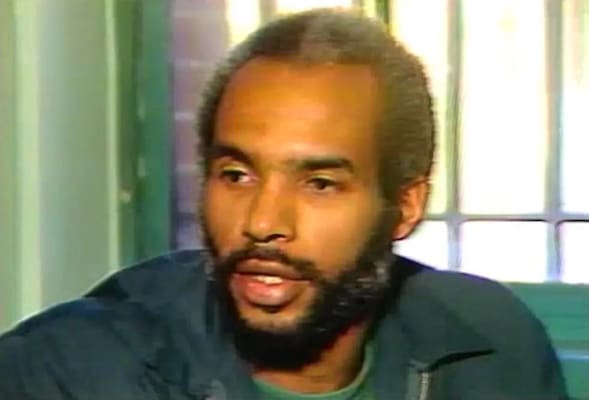

Kuwasi Balagoon, born Donald Weems on December 22, 1946, was an exemplary example of synthesized theory and praxis. Growing up in Prince George’s County in Maryland, the teenaged Weems had witnessed the militancy of Gloria Richardson and the movement in Cambridge. Africans in the Eastern Shore organized snipers to protect protesters from white supremacists terrorizing the community. Eventually, a treaty was negotiated by the Justice Department and U.S. Attorney General Robert Kennedy, an incident that left a lasting impression on the young African. Upon graduating from high school, Weems enlisted in the army where he and many other Africans experienced racism from fellow officers and disproportionate punishment from the higher-ups. Taking matters into their own hands, a few of them conspired and created a clandestine formation based on “fucking up racists” called De Legislators. “We were De Judge, De Prosecutor, De Executioner, Hannibal, and De Prophet. We said we would go to jail for a reason and not the season” he expounded in his autobiography alongside other Panthers in Look For Me In The Whirlwind.

After serving in the military and receiving an honorable discharge, Weems moved to New York City where his sister Diane lived. In New York City, Weems got involved in rent strikes and worked as a tenant organizer for the Community Council on Housing under Jesse Gray, leader of the CCH. Jesse Gray used the militant language of Black nationalism to attract young recruits. Frustrated with the failure of the local government to address the poor conditions of urban housing, most notably rat infestations, Weems and members of the CCH traveled to Washington, DC. They attended a session of congress unannounced and uninvited with a cage of rats in tow and disrupted the session. After brawling with cops and being arrested for disorderly conduct, CCH lost its funding and Weems eventually moved on from the organization.

A Yoruba Temple in Harlem offered a nationalistic, religious and cultural means of self-determination to local Africans. It was there Weems rejected his slave name like many others in the Black Panther Party in New York City would eventually do. In his spare time, he would associate with the Yoruba Temple which led to his renaming. “Kuwasi,” meaning “born on a Sunday” and “Balagoon,” a Yoruba name meaning “warlord”. Through his revolutionary praxis, Balagoon would later prove that he indeed had a knack for urban guerrilla warfare.

Revolutionary Black nationalism resonated with Balagoon during a time when non-violence was emphasized by many Africans in the Civil Rights movement. He read Negroes With Guns by Robert F. Williams, the Autobiography of Malcolm X and was inspired by Jamil Abdullah Al-Amin, then known as H.Rap Brown. When Huey P. Newton made national headlines in 1967 after a shoot-out with members of the Oakland police department and survived that confrontation, Balagoon was inspired and felt that the BPP had a program that he could get behind. The next year when Balagoon heard the BPP was organizing in New York, he located the Harlem chapter and joined.

The BPP’s emphasis on community based organizing and the Mao-inspired assertion of armed struggle resonated with him. Unlike the West Coast chapters which focused on survival programs like the Free Breakfast program, the New York chapters focused on tenant organizing among other initiatives, such as the community takeover of Lincoln Hospital in coalition with the Young Lords and the Provisional Government of the Republic of New Afrika to reform the detox program. Balagoon’s experience as a tenant organizer helped establish him as a key member alongside his willingness to take on any task, no matter how big or small. Despite his engagement in grassroots organizing and revolutionary ideology, Balagoon was attracted to the underground wing of the Black Panther Party, the Black Liberation Army.

In February of 1969, Balagoon and Richard Harris, also a member of the BPP, were arrested on bank robbery charges in Newark, New Jersey. A few months later in April 1969, 21 Panther organizers including Balagoon and Harris were indicted and several others arrested on conspiracy charges to bomb the New York Botanical Gardens and police stations. We would later learn this conspiracy was an attempt by COINTELPRO to deradicalize and defang the movement that the BPP was successfully building. Many of the defendants were released on bail, but Balagoon was held without bail. After two years and the acquittal of all charges for the rest of the group, Balagoon plead guilty to charges that he and an unidentified person planned to ambush police officers in January of 1969 but was interrupted by other officers arriving on the scene. This left him the only one of the twenty-one defendants to be convicted.

As tensions grew between the West Coast faction of the BPP and the New York chapters, the Panther 21 defendants publicly took a critical position on the national leadership in an open letter to the Weather Underground. This led to the expulsion of the Panther 21 by Huey Newton in 1971. After this incident, Balagoon started to question the nature of “democracy” in the organization. He also felt that it was important to correct the ideological weaknesses that compromised their capacity to fight and resist state repression. His experience in prison awaiting trial contributed to his ideological transition to anarchism. Groups like the Anarchist Black Cross (who also influenced and supported Lorenzo Kom’Boa Ervin, another anarchist out of the BPP) sent Balagoon literature which he studied. Anarchism gave Balagoon a tool of analysis through which he was able to critique his experience in the BPP. “The cadre accepted their command regardless of what their intellect had or had not made clear to them. The true democratic process which they were willing to die for, for the sake of their children, they would not claim for themselves.”

He was influenced by the likes of Errico Malatesta, Jose Buenaventura Durruti Dumange, Servino Di Giovanni and Emma Goldman. Emma Goldman spoke of “free love,” which resonated with Balagoon who was bisexual. Like other BLA members, he adopted “New Afrikan” as his national identity recognizing Africans in the U.S. as an internal colony. Alongside his staunch anti-capitalist, anti-imperialist perspective, this led to him identifying as a New Afrikan Anarchist. In prison he struggled with Marxist-Leninists, nationalist political prisoners, recruited members for the BLA and politicized many other prisoners in the process. During a coordinated rebellion in the Queens House of Detention, Balagoon sought a process of a total consensus from all prisoners and took a step back when he recognized his influence on this process. He encouraged the other prisoners to come to a general consensus instead of looking to him as the de facto leader. He converted many to anti-authoritarian and New Afrikan politics. During his time in the kamps Balagoon recognized himself to be a New Afrikan Prisoner of War.

Deciding he had an obligation to contribute to the outside struggle, Balagoon escaped Rahway State Prison on September 23, 1973. Less than a year later, he was recaptured attempting to help his comrade Richard Harris escape custody while being transported to a funeral in Newark. They were captured after a gun battle with police and correctional officers and were wounded in the fire-fight. Balagoon could have chosen to lay-low and organize in other capacities but was committed to his comrades and was willing to sacrifice his life to save another. On May 27, 1978, Balagoon escaped Rahway State Prison again and joined BLA members in alliance with militant white radicals who stood in solidarity with the Black Liberation Movement. They formed a network called the Revolutionary Armed Task Force, or RATF. They were Muslims, revolutionary nationalists, communists, anarchists (Balagoon the sole anarchist) and anti-imperialists. Despite being critical of nationalism and even Marxism, Balagoon’s love for his’rades like Sekou Odinga (who was a major leader of this formation) allowed him to unite with the others on the basis of certain principles. Those principles being anti-capitalist, anti-imperialist and against white supremacy. Despite his sexuality and ideological differences, Balagoon garnered respect from his ‘rades due to his commitment to revolutionary struggle.

The BLA wing was called the “New Afrikan Freedom Fighters” and organized in response to recent acts of violence against Africans which consisted of shootings of children, women and other acts of brutality. BLA members saw to it that it would be understood that when Africans were killed as a result of racist state violence, there would be a response from members of the Underground. The white comrades in the RATF gathered intelligence on white paramilitary groups like the Ku Klux Klan and other right-wing activity to gauge fighting capability. The RATF took part in bank expropriations to obtain resources to fund the Black Liberation Movement. One of the most notable actions of the RATF was the liberation of Assata Shakur from Clinton Correctional Institution for Women in New Jersey.

Assata Shakur was a member of the New York BPP who eventually went underground as a result of state repression. On May 2, 1973, a shootout on the turnpike between New Jersey state troops and BLA members ensued. When the smoke cleared, one pig was pronounced dead, comrade Zayd Malik Shakur fatally wounded and Assata Shakur herself wounded and paralyzed as a result of being shot in the back, injuries she would eventually recover from. Sundiata Acoli, a defendant in the Panther 21 conspiracy case and BLA member was captured two days later. It is important to note comrade Acoli is still incarcerated as a result of this incident. Shakur was convicted of the murder of the deceased officer and Zayd Malik Shakur and was sentenced to life plus sixty-five years. Shakur was recognized as a political prisoner by many human rights advocates in the U.S. and around the world. On November 2, 1979, an armed team of four BLA members that included Odinga and Balagoon, plus two white allies from the RATF liberated comrade Shakur in an action that was well planned and executed. Shakur went underground and eventually resurfaced in Cuba where she resides to this day.

On October 20, 1981, members of the RATF and the BLA attempted to expropriate 1.6 million dollars from a Brinks armored truck in Nyack, New York. This led to a gunfight which resulted in the death of two police officers and one Brinks security guard. Three white ‘rades and a Black man were captured on the scene. Several other arrests and the death of one comrade, BLA member Mtayari Sundiata occurred as a result of the hunt on behalf of the Joint Terrorist Task Force (JTTF). The JTTF was coordinated as a joint effort between local police and the FBI in response to the liberation of Assata Shakur from the kamp in New Jersey. They asserted that Balagoon and the BLA were behind the expropriation, including many others that dated back to 1976. The money from these expropriations, a tactic of urban guerrilla warfare, went towards supporting families of political prisoners, prisoners of war, Black Liberation Movement activities, the Black Underground infrastructure and liberation struggles on the African continent.

Upon his capture, Balagoon rapped New Afrikan and anti-authoritarian politics in public statements and defined himself as a prisoner of war, not a criminal. He served as his own attorney at the Rockland County trial where he was charged with armed robbery for the action in Nyack and the murders of the two pigs and security guard. Balagoon later claimed responsibility in a news segment that aired on television. “Everybody who got shot that day was armed. Everybody who was shot that day woke up that morning with the realization that they might get shot that day.” During his trial, Balagoon used the opportunity to speak to the public about his politics and his intentions for the historical record in lieu of a “criminal” defense. Understanding himself to be a prisoner of war, at war with a predatory state, he rejected the legitimacy of the kourts and emphasized his motives as part of a larger liberation movement that sought to liberate New Afrikan people and to eliminate capitalism, imperialism and authoritarian forms of government.

Upon his sentencing to life imprisonment Balagoon continued to write statements addressing the anarchist movement and the Black Liberation Movement. He challenged anarchists to move from theory towards practice and stated: “We permit people of other ideologies to define anarchy rather than bring our views to the masses and provide models to show the contrary… In short, by not engaging in mass organizing and delivering war to the oppressors, we become anarchists in name only.” Balagoon died of AIDS in prison on December 13, 1986, nine days short of his 40th birthday.

Balagoon wrote anarchist theory and continued to organize and provide political education to prisoners. As a New Afrikan anarchist, revolutionary nationalist, Pan-Africanist, internationalist, poet, and bisexual militant, Balagoon’s greatest quality was his love for his people and his relatability to those around him. Unlike many anarchists today who emphasize individuality and are arm-chair revolutionaries supporting reactionary views on imperialism, Balagoon understood the necessity of supporting Third World liberation struggles and had an anti-imperialist stance noting any anarchist ideology incomplete without it. Despite his anarchist influences, he departed from the orthodoxy of European anarchism and applied the material conditions of Africans and African methods of organizing to bring anarchism to a higher, more radical level. Balagoon earned the nickname “Maroon” for his successful escapes from the kamps and for his militancy, expropriations and love of community, leaving no soldier behind.

Sekou Odinga would later recall Kuwasi Balagoon was a walking contradiction. As much as he was ready for dangerous work and volunteered for all tasks, he was also a babysitter, someone you’d want to leave your kids with. He enjoyed getting high and would experiment with any drug except heroin. Balagoon listened to punk music, jazz, rock-and-roll and could basically fit into any category. He frequented the Mudd Club in New York City. In A Soldier’s Story, Dhoruba Bin Wahad recalls a powerful memory of Kuwasi Balagoon. On a run down south, asking the poet to “bust a verse or two”, in regards to white supremacy he proclaimed at one point “white folks don’t mind, and Black folks don’t matter.” Cold. Despite his many interests, there was never any separation in his mind about the struggle. The memorable saying “repression breeds resistance” was first enunciated by Balagoon in his “Statement of a New Afrikan Prisoner of War” booklet. He wrote and sketched out ideas of physical training that could be performed in the tight confines of a prison cell and gave it to ‘rades to help them stay solid for survival. At the time of his arrest, he was captured with his transgender lover and many in the movement made disparaging comments about them. Even the radical and militant left was hostile towards queer folks and comrades in those days, something the movement today has yet to reckon with. Despite his many contributions to the struggle, folks chose to remain committed to their reactionary judgements on sexuality and gender.

Kuwasi Balagoon rejected bourgeois notions of love and sexuality, remained committed to his comrades, the struggle and lived life to the absolute fullest demonstrating to many what a revolutionary of the highest order could be. He was committed to freedom and exercising self-determination by any means necessary. Kuwasi’s selfless, revolutionary love practiced by all in the struggle today would bring us closer to unity of one heart, one mind. Kuwasi Balagoon and many others left us blueprints for how to get free. In our continued efforts to break de chains, let us follow his advice: “Let’s keep the American and Canadian flags flying at half-mast…i refuse to believe that Direct Action has been captured.” Right on. Love, power and peace by piece.

Rhamier Shaka Balagoon (F.K.A. Rhamier Auguste): is a cultural worker, community intellectual and organizer based in New York City. They are a member of the Black Alliance for Peace where they are a core member of the local city alliance and a member of the Research and Political Education team.