eff Cohen (Common Dreams, 2/28/22): “Unfortunately, there was virtually no focus on civilian death and agony when it was the U.S. military launching the invasions.”

As U.S. news media covered the first shocking weeks of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, some media observers—like FAIR founder Jeff Cohen (Common Dreams, 2/28/22)—have noted their impressions of how coverage differed from wars past, particularly in terms of a new focus on the impact on civilians.

To quantify and deepen these observations, FAIR studied the first week of coverage of the Ukraine war (2/24–3/2/22) on ABC World News Tonight, CBS Evening News and NBC Nightly News. We used the Nexis news database to count both sources (whose voices get to be heard?) and segments (what angles are covered?) about Ukraine during the study period. Comparing this coverage to that of other conflicts reveals both a familiar reliance on U.S. officials to frame events, as well as a newfound ability to cover the impact on civilians—when those civilians are white and under attack by an official U.S. enemy, rather than by the U.S. itself.

Ukrainian sources—no experts

One of the most striking things about early coverage has been the sheer number of Ukrainian sources. FAIR always challenges news media to seek out the perspective of those most impacted by events, and U.S. outlets are doing so to a much greater extent in this war than in any war in recent history. Of 234 total sources—230 of whom had identifiable nationalities—119 were Ukrainian (including five living in the United States.)

However, these were overwhelmingly person-on-the-street interviews that rarely consisted of more than one or two lines. Even the three Ukrainian individuals identified as having a relevant professional expertise—two doctors and a journalist—spoke only of their personal experience of the war. Twenty-one (17% of Ukrainian sources) were current or former government or military officials.

Airing so many Ukrainian voices, but asking so few to provide actual analysis, has the effect of generating sympathy, but for a people painted primarily as pawns or victims, rather than as having valuable knowledge, history and potential contributions to determine their own futures.

Meanwhile, Russian government sources only appeared four times. Sixteen other Russian sources were quoted: 13 persons on the street, an opposition politician and two members of wealthy families.

Eighty sources were from the United States, including 57 current or former U.S. officials. Despite the diplomatic involvement of the European Union, only two Western European sources were featured: the Norwegian NATO Secretary General and a German civilian helping refugees in Poland. There were also eight foreign civilians featured living in Ukraine: three from the U.S., three African and two Middle Eastern.

For Ukrainian-American reaction to the Russian invasion, CBS (2/24/22) turned to the leader of a group that “played a leading role in opposing federal investigations of suspected Nazi war criminals” (Salon, 2/25/14).

And while political leaders certainly bring important knowledge and perspective to war coverage, so too do scholars, think tanks and civic organizations with regional expertise. But these voices were almost completely marginalized, with only five such civil society experts appearing during the study period. All were in the United States, although one was Ukrainian-American Michael Sawkiw (CBS, 2/24/22), who represented the Ukrainian Congress Committee of America (an organization associated with Stepan Bandera’s faction of the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists, which participated in the Holocaust during World War II).

In effect, then, U.S. news media have largely allowed U.S. officials to frame the terms of the conflict for viewers. While officials lambasted the Russian government and emphasized “what we’re going to do to help the Ukrainian people in the struggle” (NBC, 3/1/22), no sources questioned the U.S.’s own role in contributing to the conflict (FAIR.org, 3/4/22), or the impact of Western sanctions on Russian civilians.

The bias in favor of U.S. officials, and the marginalization of experts from the country being invaded—as well as civil society experts from any country—recalls U.S. TV news coverage of another large-scale invasion in recent history: the U.S. invasion of Iraq. A FAIR study (Extra!, 5–6/03) at the time found that in the three weeks after the U.S. launched that war, current and former U.S. officials made up more than half (52%) of all sources on the primetime news programs on ABC, CBS, NBC, CNN, Fox and PBS. Iraqis were only 12% of sources, and 4% of all sources were academic, think tank or NGO representatives.

In other words, though the bias is even greater when the U.S. is leading the war, U.S. media seem content to let U.S. officials fashion the narrative around any war, and to mute their critics.

Visible and invisible civilians

But there are striking differences as well in coverage of the two wars. Most notably, when the U.S. invaded Iraq, civilians in the country made up a far smaller percentage of sources: 8% to Ukraine’s 45%.

U.S. reporters, almost all of them embedded with the U.S. military in Iraq at the beginning of the war, absorbed and regurgitated U.S. propaganda that painted the war as liberating Iraqis, not killing them. There was little motivation, then, to talk to or feature them, except to show them praising the U.S.—the kind of reaction that a journalist embedding with heavily armed soldiers was likely to produce.

Another noteworthy difference is the way U.S. news media cover antiwar voices from the aggressor nation. Interestingly, Russian public opposition to the Ukraine war appears to be roughly similar to U.S. public opposition to the Iraq War, in that while a majority in each country supported their government’s aggressive actions at the start of both wars, around a quarter opposed them (Gallup, 3/24/03; Meduza, 3/7/22).

But on U.S. TV news, antiwar sentiment appeared starkly different in the two conflicts. Of the 20 Russian sources in the study, ten (50%) expressed opposition to the war, significantly higher than the proportion polls were showing. Meanwhile, antiwar voices represented only 3% of all U.S. sources in early Iraq coverage (FAIR.org, 5/03), a dramatic downplaying of public opposition.

Civilian-centered war coverage

In the Ukraine invasion, U.S. TV news coverage focused appropriately on the civilians who pay the highest price in modern warfare (ABC, 2/28/22)—but this focus was largely missing in reporting on U.S.-led wars.

The brunt of modern wars is almost always borne by innocent civilians. But U.S. media coverage of that civilian toll is rarely in sharp focus, such that recent reporting on Russia’s invasion of Ukraine offers an exceptional view of what civilian-centered war coverage can look like—under certain circumstances.

In our study, we looked not just at sources, but also the content of segments about Ukraine. In the first week of the war, the U.S. primetime news broadcasts on ABC, CBS and NBC offered regular reports on the civilian toll of the invasion, sending reporters to major targeted cities, as well as to border areas receiving refugees.

Seventy-one segments across the three networks covered the impact on Ukrainian civilians, both those remaining behind and those fleeing the violence. Twenty-eight of these mentioned or centered on civilian casualties.

Many reports described or aired soundbites of civilians describing their fear and the challenges they faced; several highlighted children. A representative ABC segment (2/28/22), for instance, featured correspondent Matt Gutman reporting:

This little girl on the train sobbing into her stuffed animal, just one of the more than 500,000 people leaving everything behind, fleeing in cramped trains.

Making the impact on civilians the focus of the story, and featuring their experiences, encourages sympathy for those civilians and condemnation of war. But this demonstration of news media’s ability to center the civilian impact, including civilian casualties, in Ukraine is all the more damning of their coverage of wars in which the U.S. and its allies have been the aggressors—or in which the victims have not been white.

‘They seem so like us’

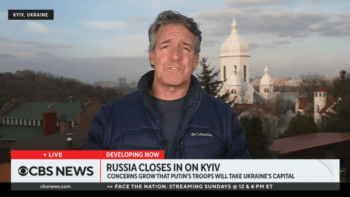

Charlie D’Agata (CBS News, 2/25/22): “This is a relatively civilized, relatively European—I have to choose those words carefully, too—city.”

Many pundits and journalists have been caught saying the quiet part loud. “They seem so like us,” wrote Daniel Hannan in the Telegraph (2/26/22). “That is what makes it so shocking.”

CBS News‘ Charlie D’Agata (2/25/22) told viewers that Ukraine

isn’t a place, with all due respect, like Iraq or Afghanistan, that has seen conflict raging for decades. This is a relatively civilized, relatively European—I have to choose those words carefully, too—city, one where you wouldn’t expect that, or hope that it’s going to happen.

“What’s compelling is, just looking at them, the way they are dressed, these are prosperous—I’m loath to use the expression—middle-class people,” marveled BBC reporter Peter Dobbie on Al Jazeera (2/27/22):

These are not obviously refugees looking to get away from areas in the Middle East that are still in a big state of war. These are not people trying to get away from areas in North Africa. They look like any European family that you would live next door to.

While U.S. news media have at times shown interest in Black and brown refugees and victims of war (e.g., Extra!, 10/15), it’s hard to imagine them ever getting the kind of massive coverage granted the Ukrainians who “look like us”—as defined by white journalists.

‘Give war a chance’

Thomas Friedman (New York Times, 4/6/99): “Twelve days of surgical bombing was never going to turn Serbia around. Let’s see what 12 weeks of less than surgical bombing does.”

And one can certainly think of instances in which non-white refugees are given short shrift by U.S. news. Despite their claims of deep concern for the people of Afghanistan as the U.S. withdrew troops last year, for example, these same TV networks have barely covered the predictable and preventable humanitarian catastrophe facing the country (FAIR.org, 12/21/21). More than 5 million Afghan civilians are either refugees or internally displaced.

The Democratic Republic of the Congo, named the world’s most neglected displacement crisis last year by the Norwegian Refugee Council (5/27/21), with 1 million externally and 5 million internally displaced, merited not a single mention in the last two years on U.S. primetime news. And in the 2000s, when an estimated 45,000 Congolese were dying of conflict-related causes every month, they mentioned it an average of less than twice a year (FAIR.org, 4/09).

At our country’s own borders, news coverage minimizes refugees’ voices, largely framing their story as a political crisis for the U.S., not a humanitarian crisis for the predominantly Black and brown refugees (FAIR.org, 6/19/21).

But being white does not automatically give civilian victims a starring role in U.S. news coverage. In the Kosovo War, Serbian victims of NATO bombing were downplayed—and sometimes their deaths even egged on—by U.S. journalists (FAIR.org, 7/99). When NATO relaxed its rules of engagement, increasing civilian casualties, New York Times columnist Thomas Friedman (4/6/99) wrote:

Twelve days of surgical bombing was never going to turn Serbia around. Let’s see what 12 weeks of less than surgical bombing does. Give war a chance.

Similarly, Washington Post columnist Charles Krauthammer (4/8/99), critical of the “excruciating selectivity” of NATO’s bombing raids, cheered that “finally they are hitting targets—power plants, fuel depots, bridges, airports, television transmitters—that may indeed kill the enemy and civilians nearby.”

‘Designed to kill only targets’

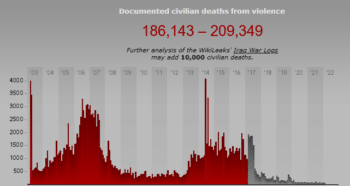

Iraq Body Count notes that “gaps in recording and reporting suggest that even our highest totals to date may be missing many civilian deaths from violence.”

As these examples suggest, while race might inform journalists’ feelings of identification with civilian victims, in a corporate media ecosystem that relies so heavily on U.S. officials to define and frame events, the interests of those officials will necessarily shape which crises get more coverage and which actors more sympathy.

The Iraq War offers a clear contrast to Ukraine coverage. The U.S. invaded Iraq on pretenses of concern about both Saddam Hussein’s supposed weapons of mass destruction and his treatment of the Iraqi people—pitching war as humanitarianism (FAIR.org, 4/9/21). But Iraq Body Count recorded 3,986 violent civilian deaths from the war in March 2003 alone; the invasion began March 20, meaning those deaths occurred in under two weeks. (The IBC numbers—which are almost certainly an undercount—documented some 200,000 civilian deaths over the course of the war.) The U.S.-led coalition was overwhelmingly responsible for these deaths.

(While the war ultimately resulted in over 9 million Iraqi refugees or internally displaced people, that displacement did not begin to reach its massive numbers until later on, so early coverage would not be expected to focus on refugees in the same way that Ukraine coverage does.)

During the first week of the Iraq War (3/20–26/03), we found 32 segments on the primetime news programs of ABC, CBS and NBC that mentioned civilians and the war’s impact on them—less than half the number those same news programs aired about Ukrainian civilians.

Remarkably, only nine of these segments identified the U.S. as even potentially responsible for civilian casualties, while 12 framed the U.S. either as acting to avoid harming civilians or as working to help civilians imperiled by Hussein’s actions. NBC‘s Jim Miklaszewski (3/21/03), for instance, informed viewers that though “more than 1,000 weapons pounded Baghdad today…every weapon is precision-guided, deadly accuracy designed to kill only the targets, not innocent civilians.”

In Ukraine coverage, by contrast, these shows named Russia as the perpetrator in every single one of the 28 mentions of civilian casualties, except in one brief headline announcement about a tank crushing a car with a civilian inside (ABC, 2/25/22); that incident was expanded upon later in the show to clearly identify the tank as Russian.

‘A direct desult of Saddam‘

Viewers of CBS Evening News did not hear until the very end of the first week of the U.S. invasion of Iraq any mention of U.S.-perpetrated harm to civilians—though they did hear that Iraqi fighters were dressing as civilians and then firing at U.S. troops (3/23/03, 3/24/03); that in one city, U.S. coalition forces “are not firing into the center of the city because we cannot risk the collateral damage” (3/25/03); and that in a nearby town, “allied forces bring the first water relief to desperate Iraqi civilians” cut off by Hussein (3/25/03). The show briefly mentioned civilian casualties twice (3/24/03, 3/26/03) without identifying the side responsible for the injuries, though one (3/24/03) emphasized that the appearance of a wounded Iraqi family at a U.S. camp “brought these [U.S.] soldiers streaming out to give what aid they could.”

After U.S. airstrikes ravaged a residential area of Baghdad on March 25, the U.S. military’s carefully curated media management began to show some cracks—but not all outlets were ready to acknowledge U.S. responsibility. To CBS‘s Dan Rather (3/26/03):

Scenes of civilian carnage in Baghdad, however they happened and whoever caused them, today quickly became part of a propaganda war, the very thing U.S. military planners have tried to avoid.

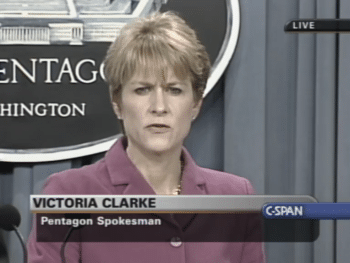

Pentagon spokesperson Victoria Clarke (C-SPAN, 3/26/03): “Any casualty that occurs, any death that occurs, is a direct result of Saddam Hussein’s policies.”

Even in coverage that didn’t wave off civilian casualties as propaganda, journalists often danced around the responsibility for them, softening the critique. On one NBC segment (3/26/03), for instance, Peter Arnett never used an active voice to identify the perpetrator of strikes on civilians and civilian areas, circling around it with lines like: “We get the sense that Baghdad is becoming increasingly a target,” or “First, with the television station and now with bombing closer to the center of the city,” or “the whole area was devastated” or “When these missiles came into the city today, the city was relatively crowded.” Instead, at the end he described “American troops” as “massing to attack Baghdad”—as if the bombing described was not already an attack by American troops.

Combined with the repeated mentions of “human shields” and Iraqi fighters “dressing as civilians,” this kind of coverage directly fed the Pentagon line as enunciated by spokesperson Torie Clarke (C-SPAN, 3/26/03):

We go to extraordinary efforts to reduce the likelihood of those casualties. Any casualty that occurs, any death that occurs, is a direct result of Saddam Hussein’s policies.

Iraqi civilians may well have been of less interest than Ukrainians to U.S. reporters because they didn’t “seem like us.” But their deaths were certainly covered less because they didn’t fit with the official line journalists were parroting.

‘Perverse to focus too much on casualties’

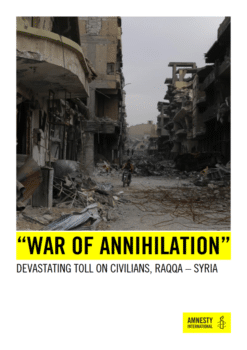

Amnesty International (4/19) on the U.S.-led assault on Raqqa, Syria: “In all the cases detailed in this report, Coalition forces launched air strikes on buildings full of civilians using wide–area effect munitions, which could be expected to destroy the buildings.”

The U.S. launched the Iraq War almost 20 years ago, but news coverage of civilian victims of U.S. aggression has changed little over time. Throughout the ongoing Syrian civil war, the U.S. has intervened to varying degrees, with a major escalation under Donald Trump in 2017. From June through October of that year, a U.S.-led coalition pummeled the densely populated city of Raqqa, which had been taken over by ISIS, with a brutal air war.

Amnesty International (4/19) accused the coalition of destroying the city with air and artillery strikes, killing more than 1,600 civilians—ten times the number the U.S. and its allies admitted to—and wounding many more. More than 11,000 buildings were destroyed. As the New Yorker‘s Anand Gopal (12/21/20) wrote, “The decimation of Raqqa is unlike anything seen in an American conflict since the Second World War.”

During the five months in which the offensive took place, only 18 segments on the three networks’ primetime news shows mentioned civilians in Syria. On ABC and NBC, the only references to civilian casualties were mentions of Trump highlighting an earlier deadly chemical weapon attack by Syrian forces elsewhere in the country (ABC, 6/27/17; NBC, 6/27/17). (CBS also mentioned the attack in the study period—7/17/17.) In fact, up to this day, neither ABC World News Tonight nor NBC Nightly News have made any mention of U.S. attacks on civilians in Raqqa, despite the release of not one but two damning reports by Amnesty International (6/5/18, 4/19).

Only nine of the 17 segments mentioned civilians in Raqqa; all of them came from CBS, which was the only network of the three that bothered to send a correspondent to the city the network’s country was bombing. CBS correspondent Holly Williams filed eight reports that mentioned civilian casualties, from August 24 to October 17. Six of these named U.S. airstrikes as causing civilian deaths, but each report mentioned in the same breath ISIS brutality against civilians or use of human shields, as if to absolve the U.S. or shift the blame to ISIS.

For instance, on October 10, Williams reported:

Without American airstrikes, defeating ISIS would have been near impossible. But some of those now escaping ISIS territory say it’s the strikes that are their biggest fear. The U.S. coalition admits that more than 700 civilians have been inadvertently killed in Syria and Iraq, others claim the number is far higher.

For Renas Halep, though, anyone who wants to destroy ISIS is a friend. He told us ISIS falsely accused him of stealing and amputated his hand four years ago. It’s a punishment the extremists have used extensively.

This “balance” is suspiciously consistent. It’s worth remembering that during the Afghanistan War, CNN chair Walter Isaacson ordered his staff to offset coverage of civilian devastation with reminders of the Taliban’s brutality, saying it “seems perverse to focus too much on the casualties or hardship in Afghanistan” (FAIR.org, 11/1/01).

None of Williams’ on-camera sources criticized U.S. coalition airstrikes, while many criticized ISIS—perhaps by CBS policy, or perhaps a function of Williams being embedded with coalition forces.

‘The booms of distant wars’

As the Russian invasion of Ukraine commenced, NBC anchor Lester Holt (2/25/22) mused:

Tonight, there are at least 27 armed conflicts raging on this planet. Yet so often the booms of distant wars fade before they reach our consciousness. Other times, raw calculations of shared national interests close that distance. But as we are reminded again in images from Ukraine, the pain of war is borderless.

Holt spoke as though journalists like himself play no role in determining which wars reach our consciousness and which fade. The pain of war might be borderless, but international responses to that pain depend very much on the sympathy generated by journalists through their coverage of it. And Western journalists have made very clear which victims’ pain is most newsworthy to them.