Though Bandung in Indonesia and Havana in Cuba couldn’t be farther apart geographically–with each city located on two distant islands in their respective countries and separated by more than 17,000km–they have been ideologically close in the imaginations of many people across the global South.

The Third World Project, born out of the continuous collaboration between the newly independent states and their struggles for national liberation, has defined and continues to define the history of the movements for peace and non-alignment even today.

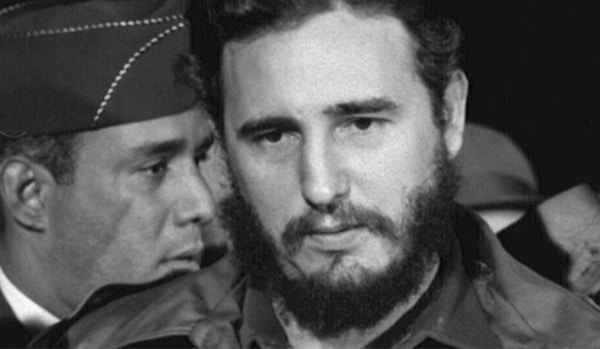

When the Bandung conference began on April 18 1955, Fidel Castro was still a political prisoner on what was then called the Isle of Pines, just south of Havana.

He was serving a 15-year sentence for having organised a failed attack on the Moncada Barracks just two years before.

In those prison years, during which a young Fidel read voraciously, he began to solidify his ideas on the concepts of sovereignty and independence and how they had to be redefined during the cold war, when imperialism was developing new approaches about how to continue with the subjugation of whole continents.

As Fidel and his comrades in prison charted a new path for Cuba, it was clear that their cause for national liberation had to be closely connected to a broader project of ensuring development and work toward active non-alignment for the people of the Third World.

From the round table of Bandung in Indonesia, the leaders of the Third World unleashed a global struggle to restructure the prevailing world system of that time.

The conference witnessed the convergence of socialist countries and the Third World and saw a growing unity among these nations in the struggles to deepen the process of decolonisation.

While at the Bandung conference, the independent governments of Asia and Africa raised the urgency of reviving the anti-imperialist and anti-colonial struggle and the need to increasingly unite and solidify the interests and aspirations of their people.

The vast majority of the governments of Latin America, meanwhile, went against the common interests and aspirations of their people, and further submitted to U.S. imperialism under the guise of the Organisation of American States (OAS), already functioning as the “ministry of colonies” of the U.S. Department of State, as Fidel would later call it.

In 1959, the Cuban Revolution triumphed. It marked a transformative point of no return for Latin America and its relations with the United States, whose government would later decide not to recognise the revolutionary process on the island.

By 1961, Cuba became the focal point of U.S. aggression in the region, leading to a blockade that has now lasted six decades.

For the first time in history, a guerilla movement had carried out a revolution and confronted U.S. imperialism right under its nose, unleashing far-reaching transformations in its socioeconomic structure, which were opposed to the neocolonial interests of U.S.

Soon after, Cuba became the only country in Latin America to join the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM), created in Yugoslavia in 1961.

Fidel and the Cuban Revolution would begin to play a strategic role in internationalist solidarity with the anti-imperialist and anti-colonial liberation struggles of the people of the Third World.

The Cuban Revolution was fully aware that its destiny was at one with that of the people of Latin America, Asia and Africa.

As Fidel said in 1962:

What is the history of Cuba if not the history of Latin America? And what is the history of Latin America if not the history of Asia, Africa, and Oceania? And what is the history of all these people if not the history of the most ruthless and cruel exploitation of imperialism in the entire world?

When Cuba joined the NAM in 1961, its foreign policy was at a stage of strategic definition.

Cuba’s commitment to the Third World became a pillar of its internationalist strategy, whether through the NAM or the Tricontinental Conference, or the subsequent Organisation of Solidarity of the People of Asia, Africa and Latin America (OSPAAAL).

In the coming decades, many of the national liberation movements that met in Havana in January 1966–during the first conference of OSPAAAL–would be among the new states that began to participate in the NAM, becoming the new Third World paradigm.

At the founding meeting of the NAM in Belgrade–then the capital of socialist Yugoslavia–in 1961, Cuba’s president Osvaldo Dorticos Torrado stated that non-alignment “didn’t mean that we are not committed countries. We are committed to our own principles.

“And those of us who are peace-loving people, who struggle to assert their sovereignty, and to achieve the fullness of national development, are, finally, committed to responding to those transcendent aspirations and not betraying those principles.”

At a time when many criticised Cuba’s apparent “alignment” with the Soviet Union and attacked the premise of national liberation being tied to a socialist project, Dorticos sought to further define non-alignment, stating that the moment required “more than general formulations, [and that] concrete problems must be considered.”

This active definition of nonalignment has been important for Cuba’s foreign policy in its relationship with the most progressive forces of the Third World.

The thinking of the NAM, starting from 1973, seems to have abandoned the ideas about “neutrality” that had permeated the movement since its creation and has expanded its activities to international economic relations with much more force than in its previous period, in defence of the need for a new international economic order.

Since the fall of the USSR, and the rise of the U.S. to a position of near hegemony, the NAM struggled to adapt to the new realities and came adrift.

In recent years, however, with the revival of regionalism in Latin America, and with the emergence of Eurasian integration, the importance of non-alignment and the NAM are being gradually considered once again.

People around the world are resistant to the coercion tactics adopted by the U.S., which has been trying to isolate countries that do not submit to the will of Washington.

This has especially become clear with the June 2022 Organisation of American States’ Summit of the Americas, where countries such as Bolivia and Mexico have threatened to boycott the summit in Los Angeles if Cuba, Nicaragua and Venezuela are banned from attending it.

As an alternative, the People’s Summit for Democracy—June 8-10 2022 in Los Angeles California–carries forth the legacy of Bandung and Havana, bringing together the voices of the excluded.

This article was produced by the Morning Star and Globetrotter.