Dec. 8 marked the 35th anniversary of the signing of the intermediate nuclear forces (INF) treaty. This landmark arms control event was the byproduct of years of hard-nose negotiations capped off by the political courage of U.S. President Ronald Reagan and Soviet General Secretary Mikhail Gorbachev who together signed the treaty and oversaw its ratification by their respective legislatures.

The first inspectors went to work on July 1, 1988. I was fortunate to count myself among them.

In August 2019, former President Donald Trump withdrew the U.S. from the INF treaty; Russia followed shortly thereafter, and this foundational arms control agreement was no more.

The Decline of Arms Control

The termination of the INF treaty is part and parcel of an overall trend which has seen arms control as an institution–and a concept–decline in the eyes of policy makers in both Washington and Moscow. This point was driven home during a two-day period where I marked the INF anniversary with veteran arms control professionals from both the U.S. and Russia.

These experts, drawn from the ranks of the diplomatic corps who negotiated the treaty, the military and civilian personnel who implemented the treaty others from all walks of life who were affiliated with the treaty in one shape or another, all had something to say about the current state of U.S.-Russian arms control.

[ Related: Sometimes Humanity Gets it Right, Scott Ritter, Consortium News.]

One thing that struck me was the importance of language in defining arms control expectations amongst the different players. Words have meaning, and one of the critical aspects of any arms control negotiation is to ensure that the treaty text means the same thing in both languages.

When the INF treaty was negotiated, U.S. and Soviet negotiators had the benefit of decades of negotiating history regarding the anti-ballistic missiles (ABM) treaty, the strategic arms limitation talks (SALT), and START, from which a common lexicon of agreed-upon arms control terminology was created.

Over the years, this lexicon helped streamline both the negotiation and implementation of various arms control agreements, ensuring that everyone was on the same page when it came to defining what had been committed to.

Today, however, after having listened to these veteran arms control professionals, it was clear to me that a common lexicon of arms control terminology no longer existed–words that once had a shared definition now meant different things to different people, and this definition gap could—and indeed would–further devolve as each side pursued their respective vision of arms control devoid of any meaningful contact with the other.

The U.S. Lexicon

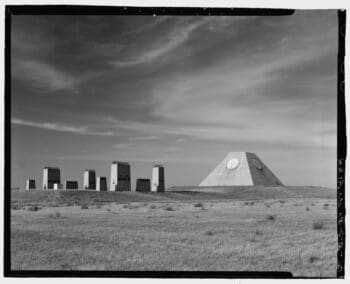

Missile site control building at the Stanley R. Mickelsen Safeguard Complex, North Dakota, 1992. Under the ABM Treaty the U.S. was permitted to deploy a single ABM system protecting an area containing ICBM launchers. (National Park Service/Wikimedia Commons)

Disarmament. Apparently, disarmament doesn’t mean what it once did to the U.S.—the actual verifiable elimination of designated weapons and capability. In fact, disarmament and its corollary, reduction, are no longer in vogue amongst the U.S. arms control community. Instead, there is an arms control process designed to promote the national security interest. And by arms control, we mean arms increase.

America, it seems, is no longer in the arms reduction business. We did away with the ABM and INF treaties, and as a result we are deploying a new generation of ballistic missile defense systems and intermediate-range weapons. While this is disconcerting enough, the real threat comes if and when the only remaining arms control agreement between the U.S. and Russia–the New START treaty–expires in February 2026.

If there is not a replacement treaty of similar capacity negotiated, ratified and ready for implementation at that time, then the notion of strategic arms control will be completely untethered from any controlling mechanism. The U.S. would then be free to modernize and expand its strategic nuclear weapons arsenal. Disarmament, it seems, means the exact opposite–rearmament. George Orwell would be proud.

The Interagency. Back when the INF treaty was negotiated and implemented, the United States was graced with a single point of contact for arms control matters —t he Arms Control and Disarmament Agency, or ACDA. Formed by President John F. Kennedy in the early 1960’s, ACDA provided the foundation for continuity and consistency for U.S. arms control policy, even as the White House changed hands.

While there were numerous bureaucratic stakeholders involved in formulating and executing U.S. arms control policy, ACDA helped ride herd over their often-competing visions through what was known as the interagency process—a system of coordinating groups and committees that brought the various players around one table to hammer out a unified vision for disarmament and arms control. The interagency was, however, a process, not a standalone entity.

How times have changed. Today, ACDA is gone. In its place is what is referred to as The Interagency. More than a simple process, The Interagency has morphed into a standalone policy making entity that is more than simply the combined power of its constituent components, but rather a looming reality that dominates arms control policy decision making.

The Interagency has moved away from being a process designed to streamline policy making, and instead transformed into a singular entity whose mission is to resist change and preserve existing power structures.

Whereas previously the various departments and agencies that make up the U.S. national security enterprise could shape and mold the interagency process in a manner which facilitated policy formulation and implementation, today The Interagency serves as a permanent brake on progress, a mechanism where new policy initiatives disappear into, never to be seen again.

Sole Purpose. Sole Purpose is a doctrinal concept which holds that the sole purpose of America’s nuclear arsenal is deterrence, and that American nuclear weapons exist only to respond to any nuclear attack against the United States in such a manner that the effective elimination of the nation or nations that attacked the U.S. would be guaranteed.

Sole Purpose was linked to the notion of mutually assured destruction, or MAD. Sole purpose/MAD was the cornerstone philosophy behind successive American presidential administrations. In 2002, however, the administration of President George W. Bush did away with the Sole Purpose doctrine, and instead adopted a nuclear posture which held that the U.S. could use nuclear weapons preemptively, even in certain non-nuclear scenarios.

Barack Obama, upon winning the presidency, promised to do away with the Bush-era policy of preemption but, when his eight-year tenure as the American commander in chief was complete, the policy of nuclear preemption remained in place. Obama’s successor, Donald Trump, not only retained the policy of nuclear preemption, but expanded it to create even more possibilities for the use of U.S. nuclear weapons.

Joe Biden, the current occupant of the White House, campaigned on a promise to restore Sole Purpose to its original intent. However, upon assuming office, Biden’s Sole Purpose policy ran headfirst into The Interagency which, according to someone in the know, was not ready for such a change.

Instead, Sole Purpose has been re-purposed to the extent that it now reflects a policy posture of nuclear pre-emption. You got that right—thanks to The Interagency, the sole purpose of American nuclear weapons today is to be prepared to carry out preemptive attacks against looming or imminent threats. This, The Interagency believes, represents the best deterrent model available to promote the general welfare and greater good of the American people.

The Russian Lexicon

The Kremlin (A.Savin, WikiCommons)

Reciprocity. Reciprocity is the Golden Rule of arms control–do unto others as you would have others do unto you. It was the heart and sole on the INF treaty–what was good for the Goose was always good for the Gander. In short, if the Americans mistreated the Soviet inspectors, one could guarantee that, in short order, American inspectors were certain to encounter precisely the same mistreatment.

Reciprocity was the concept which prevented the treaty from getting bogged down in petty matters and allowed the treaty to accomplish the enormous successes it enjoyed.

Under the terms of the New START treaty, each side is permitted to conduct up to 18 inspections per year. Before being halted in 2020 because of the pandemic, a total of 328 inspections had been carried out by both sides with the rules of reciprocity firmly in place and adhered to.

However, in early 2021, when both sides agreed that inspections could resume, the U.S. demonstrated the reality that the concept of reciprocity was little more than a propaganda ploy to make Russia feel “equal” in the eyes of the treaty.

When the Russians attempted to carry out an inspection in July, the aircraft carrying the inspection team was denied permission to fly through the airspace of European countries due to sanctions banning commercial flights to and from Russia in the aftermath of the Russian invasion of Ukraine. The Russians cancelled the inspection.

Later, in August, the U.S. tried to dispatch its own inspection team to Russia. The Russians, however, denied the team permission to enter, citing issues of reciprocity–if Russian inspectors could not carry out their inspection tasks, then the U.S. would be similarly denied.

For Russia, the definition of reciprocity is quite clear–equal treatment under the terms of a treaty. For the U.S., however, reciprocity is just another concept which it can use to shape and sustain the unilateral advantages it has accrued over the years when it came to implementing the New Start treaty.

Predictability. Historically, the primary purpose of arms control agreements was to reach a common understanding of mutual objectives and the means to achieve them so that over the agreed upon timeframe there would exist an element of stability from the predictability of the agreement.

This, of course, required agreement on definitions and intent accompanied by a mutual understanding of the four corners of the deal, especially on quantifiable subjects such as treaty-limited items.

Under the INF treaty, the goals and objectives for both parties were absolute in nature: total elimination of the involved weapons which existed in a class covered by the treaty. One couldn’t get much clearer than that and by mid-1991, all weapons covered by the treaty had been destroyed by both the U.S. and Soviet Union.

Subsequent inspections were focused on ensuring both sides continued to comply with their obligation to permanently destroy the weapons systems designated for elimination and not to produce or deploy new weapons systems whose capabilities would be prohibited by the terms of the treaty.

Under New START, the goals and objectives are far more nebulous. Take, by way of example, the issue of decommissioning nuclear-capable bombers and submarine-launched ballistic missile launch tubes. The goal is to arrive at a hard number that meets the letter and intent of the treaty.

But the U.S. has undertaken to decommission both the B-52H and Trident missile launch tubes onboard Ohio-class submarines in a manner which allows for reversal, meaning that the hard caps envisioned by the treaty, and around which strategic planning and posture is derived, are not absolute, but flexible.

As such, Russian strategic planners must not only plan for a world where the treaty-imposed caps are in effect, but also the possibility of a U.S. “break out” scenario where the B-52H bombers and Trident missiles launch tubes are brought back to operational status.

This scenario is literally the textbook definition of unpredictability and is why Russia looks askance at the idea of negotiating a new arms control treaty with the U.S. As long as the U.S. favors treaty language which produces such unpredictability, Russia will more than likely opt out.

Accountability. One of the most oft-quoted sayings that emerged from the INF treaty is “trust but verify.” This aphorism helped guide that treaty through the unprecedented success of its 13-year period of mandated inspections (from 1988 until 2001.) However, once the inspections ended, the “verify” aspect of the treaty became more nebulous in nature, opening the door for the erosion of trust between the U.S. and Russia.

A key aspect of any arms control agreement is its continued relevance to the national security postures of the participating nations. At the same time the INF inspections came to an end, the administration of President George W. Bush withdrew from the landmark 1972 anti-ballistic missile (ABM) treaty.

In doing so, the United States propelled itself into a trajectory where the principles that had underpinned arms control for decades—the de-escalation of nuclear tensions through the adherence to principles of disarmament set forth in mutually-reinforcing agreements intended to be of a lasting nature, no longer applied.

By unilaterally disposing of the ABM treaty, the U.S. opened the door for the deployment of ABM systems in Europe. Two Mk. 41 Aegis Ashore anti-missile defense systems, normally deployed as part of a ship’s Aegis-capable cruisers and destroyers, were instead installed on the ground in Romania and Poland. The issue of the Mk. 41 system is that the launch pods are capable of firing either the SM-3 missile as an interceptor, or the sea-launched cruise missile (Tomahawk.)

Russia objected to the Mk. 41 potentially offense system being employed on the ground, arguing that in doing so the U.S. was violating the INF treat by deploying a ground-launched cruise missile.

The U.S. rejected the Russian allegations, declaring that the Aegis Ashore launch configuration was solely for the firing of surfacre-to-air missiles. However, the U.S. balked at providing Russia the kind of access that would be necessary to ascertain the actual science behind the U.S. claim that the missile batteries were configured to operate only in a surface-to-air mode.

The U.S. also claimed it was impossible for the Mk. 41 to incorporate the Tomahawk cruise missile or a follow-on variant of the SM-3 or the SM-6 Typhoon, which are surface-to-surface missiles at ranges (reaching Moscos) that would violate the INF treaty.

(Removal of these missiles from Poland and Romania was one demand Russia made in draft treaty proposals to the U.S. last December. After the U.S. rejected it, Russia intervened in Ukraine.)

As had been the case with the ABM treaty, the U.S. had grown tired of the restrictions imposed by the INF treaty. U.S. military planners were anxious to field a new generation of INF weapons to counter what they perceived to be the growing threat from China, whose ballistic missile arsenals were not constrained by the treaty.

The ABM and INF treaties had become inconvenient to the U.S. not because of any actions undertaken by their treaty partners, the Russians, but rather due to an aggressive, expansive notion of U.S. power projection that mooted the purpose of the treaties altogether.

Arms control treaties are not meant to facilitate the expansion of military power, but rather restrict it. By viewing treaty obligations as disposable, the U.S. was eschewing the entire philosophy behind arms control.

Moreover, the tactics employed by the U.S. to undermine the credibility of the INF treaty revolved around fabricating a case of alleged Russian violations built around “intelligence” about the development of a new Russian ground-launched cruise missile, the 9M729, which the U.S. claimed proved that the new missile was in violation of the INF treaty.

That the intelligence was never shared with the Russians, further eroded the viability of the U.S. as a treaty partner. When the Russians offered up the actual 9M729 missile for physical inspection to convince the U.S. to remain in the INF treaty, the U.S. balked, preventing not only U.S. officials from participating, but also any of its NATO allies.

In the end, the U.S. withdrew from the INF treaty in August 2019. Less than a month later, the U.S. carried out a test launch of the Tomahawk cruise missile from a Mk. 41 launch tube. The Russians had been right all along–the U.S., in abandoning the ABM treaty, had used the deployment of so-called new ABM sites as a cover for the emplacement of INF-capable ground-launched missiles on Russia’s doorstep.

And yet the U.S. pays no price–there is no accountability for such duplicity. Arms control, once a bastion of national integrity and honor, had been reduced to the status of a joke by the actions of the U.S.

No Trust Left

A UGM-133A Trident II ballistic missile is launched from the U.S. Navy Ohio-class ballistic missile submarine USS West Virginia in 2014. (U.S. Navy)

With no common language, there can be no common vision, no common purpose. Russia continues to seek arms control agreements which serve to restrict the arsenals of the involved parties to prevent dangerous escalatory actions while imposing a modicum of predictable stability on relations.

The U.S. seeks only unilateral advantage.

Until this is changed, there can be no meaningful arms control interaction between the U.S. and Russia. Not only will the New START treaty expire in February 2026, but it is also unlikely the major verification component of the treaty–on site inspections–will be revived between now and then.

Moreover, it is impossible to see how a new arms control agreement to replace the expired New START treaty could be negotiated, ratified, and implemented in the short time remaining to do so. There is no trust between Russia and the U.S. when it comes to arms control.

With no treaties, there is no verification of reality. Both the U.S. and Russian arsenals will become untethered from treaty-based constraint, leading to a new arms race for which there can be only one finishing line–total nuclear war.

There is a long list of things that must happen if meaningful arms control is ever to resume its place in the diplomatic arsenals of either the U.S. or Russia. Before either side can resume talking to one another, however, they must first re-learn the common language of disarmament.

Because the current semantics of arms control is little more than a lexicon for disaster.